Desert musical classics

It’s a long way from Mali to the Mississippi, but the musical distance is not as great as you might think. Richard Knight journeys to the source of the blues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Friday night is party night in Bamako. Across the city, on dusty back-streets, under the ever-starry Malian sky, sweating smiling crowds converge on one-room concrete music joints where, beneath a single ceiling fan, they press onto the dance-floor. Flag beer flows and the music roars.

These days, in the thick of the throng, you might see a red-faced Frenchman pogo past a reeling, beaming Brit. That's because the secret's out. Malian music is about as good as it gets; a rocking, eccentric, irresistible blend of electric guitars and hollowed-out gourds.

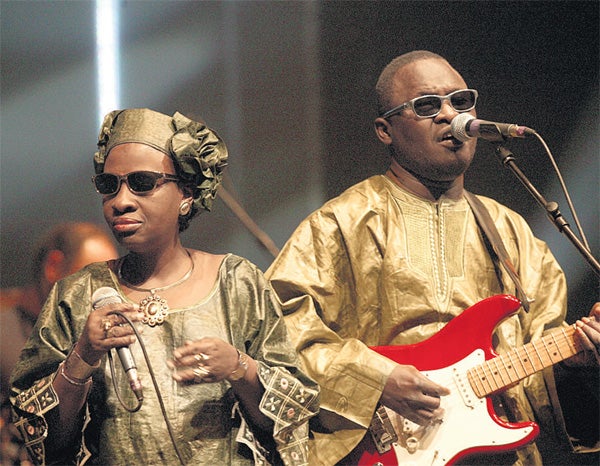

You don't have to navigate Bamako back streets to find Malian music. Stars like Salif Keita and Amadou & Mariam tour Europe often. And the musical exchange goes both ways: Ry Cooder, Corey Harris and Damon Albarn have all recorded in Mali with Malian musicians. But the connection between American, European and West African music is far older – and darker – than that. The fusion came about amid the grinding poverty of old New Orleans and on the cotton plantations of the Mississippi Delta. It happened about a hundred years ago.

By the mid-18th century, British ships carried 40,000 slaves a year from Africa to the New World. Other European nations traded with comparable efficiency; merchants from France, Holland, Portugal, Spain and Denmark scoured the west coast of Africa in search of men and women to sell to colonial landowners in the Caribbean, Spanish-controlled South America and the United States.

Buyers in America considered slaves from the area they knew as "Senegambia" to be more civilised than the rest. But beyond that simple-minded distinction, slaves were thrown together on ships and on plantations regardless of where they came from. That bringing together of disparate African traditions is one reason why, in the American South, a musical cauldron was created in which jazz and blues would eventually be brewed. While modern jazz and blues developed from a mix of many influences, and particular socio-economic conditions, there are a number of elements which were placed in that cauldron by those wretched slaves.

Along Africa's west coast, "griots" or "jalis" would sing alone with stringed instruments to deliver half-sung, half-stated monologues. They were entertainers and historians. Their stringed instruments included the kora, similar to a lute, and the halam, which evolved into the banjo. This marriage of voice and string, and their use of pitch and tone to heighten emotion, have clear echoes in blues.

In his book Deep Blues, Robert Palmer explains that many African tribes at that time used languages in which words had several meanings, depending on their pitch. Rising emotion was often expressed through falling pitch; "blue notes", of flattened thirds and fifths, are used in jazz and blues . There are clear echoes of "call and response" – a feature of communal African music – in American work songs and gospel music; and African-style drumming, it's thought, gave jazz its defining feature: syncopation.

The final catalyst for the fusion which created jazz was cultural – the coming together of black and Creole musicians in New Orleans. The quadrille, mazurka and schottische merged with the cadences, harmonies and, above all, syncopation which had been carried to the New World in the heads of slaves.

Blues grew from the cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta, where slave music was at first tolerated by plantation owners. But drums and horns were used to organise rebellion and were eventually removed. Those slaves had only their bodies, their voices and clapped rhythms, with which to make music.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Not all music scholars accept the argument that jazz and blues are built on the music of African slaves. Some point to the long gap between the arrival of slaves and the emergence of jazz and blues as distinct art forms. And it's certainly true that some elements of blues – not least the 12-bar format – are not found in African music.

But it seems to me to be beyond doubt that jazz and blues would not exist as we know them had African slaves not been forced to cross the Atlantic to the United States. Apart from anything else, that grim heritage, and the ferocious racism which followed, gave those unfortunate souls a reason to sing. Blues is nothing if not a way to purge oneself of sorrow.

Whatever the strength of the connection between West African music and that of the Deep South, I felt, standing in that pounding Bamako club, transported by the music far from the broken-up road and open sewer outside, that it's real. I felt that way because I had, years ago, stood in a club with the same vibe.

It was called Po' Monkey's and it was an improvised juke-joint in a falling-down shack at the edge of a huge, flat cotton-field near Merigold, Mississippi. As we rumbled down farm-tracks in search of this forgotten place whose name I'd heard whispered throughout the Delta, we heard it before we saw it. And when we entered we were enveloped by a crowd of joyous faces.

These were people who were determined to have a good time despite the glaring poverty which stalks the sagging shotgun houses of the rural poor in that desolate and beautiful part of the States. Whether, ultimately, musicologists can prove it, there is, I'm sure, a bridge between the music of Mali and the Mississippi Delta. Even if the common thread is no more than the shared need to escape, for just a few hours, when Friday night comes around.

Richard Knight is author of 'The Blues Highway: New Orleans to Chicago', a travel and music guide

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments