Double Fantasy at 40: John Lennon’s last album was his most revealing

After a recording hiatus, the former Beatle headed into the studio in 1980 to restart his career – three weeks after the album’s release he was murdered. Geoff Edgers tells the story of Lennon’s final artistic statement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jack Douglas could hear the telephone ringing as he approached his brownstone on New York’s Central Park West. He hustled in and grabbed the handset.

“Jack,” the voice on the line said. “You've got an amazing opportunity. But if you tell anyone, it’ll disappear.”

Douglas didn't recognise the man. And he certainly didn’t suspect the call might be connected to John Lennon.

It had been years since Douglas, a record producer and engineer, worked with the former Beatle. Lennon had stopped recording in 1974 and slipped into domestic life with his wife, Yoko Ono, and newborn son Sean. What Douglas didn’t know is that Lennon was still furiously writing songs in private, and looking to make a comeback. One of the greatest artists of his time just worried that he was no longer good enough.

That was the reason for the cryptic call in the spring of 1980: to enlist help from an old colleague who wouldn’t ask too many questions.

The stranger on the phone instructed Douglas to go down to a pier on the Hudson River, where a sea plane would pick him up. Maybe somebody else would have thought twice, but Douglas was a risk-taker. At 19, he’d paid $112 for a one-way ticket on a steamship to make a pilgrimage to The Beatles’s hometown of Liverpool. At 23, he’d talked his way in the door at a famous Manhattan recording studio by offering to work as a janitor. So, at 34, he didn't flinch when a stranger offering few details – the man remains unknown to Douglas to this day – asked him to hop on a plane for “an amazing opportunity”.

The flight took less than half an hour to land in Cold Spring Harbour on the shore of Long Island. That’s where Douglas walked into a house and was greeted by an old friend. Yoko Ono was direct in her request.

“John wants to do a record; he wants you to produce it,” she said, handing him a sealed envelope labelled “For Jack’s ears only.”

Then the telephone rang. This time the voice on the line was unmistakable – the rock star who wrote “Revolution”, “Help!” and “Imagine” and brashly declared The Beatles were more popular than Jesus. On the phone, though, Lennon sounded tentative.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

At almost 40, the singer-songwriter was at a personal and creative crossroads. Since he’d last been in a studio, disco, punk and new wave had arrived. He told Douglas he’d written some demos; they were on a pair of tapes in the envelope.

“I don't know if they’re worth anything,” he added. “You listen and I’ll call you tomorrow, and you tell me what you think.”

Double Fantasy, released 40 years ago on 17 November, is not Lennon’s best album. But it may be his most revealing, for reasons that stretch beyond the music. For an artist who always wrote songs about his life, this record in particular - highlighted by “(Just Like) Starting Over”, “Woman” and “I'm Losing You” – is the most autobiographical of all. It also serves as an important, heartbreaking coda to a singular life. Lennon wanted Double Fantasy to restart his career. Instead, his tragic death, coming three weeks after its release, turned the music he made for the album into his final artistic statement.

Double Fantasy is the best way to tell the story of Lennon’s last years, from his retreat to house-husbandhood to his return to the top 10. It opens a window into the intense and often private relationship between Lennon and Ono.

If you wanted your favourite Beatle’s latest release, you had to also take his wife as part of the purchase

“It's like a movie, though, and the script is constantly changing” is how Lennon explained it to Playboy’s David Sheff in an interview on the eve of the album’s release.

“We have some songs on the album that can be considered negative,” Ono added in the same interview, “but at the same time the fact that we can honestly state those feelings is very positive and we get a certain atonement for that.”

(Ono, 87, declined to comment for this story, through a representative. She has rarely been seen in public in recent years.)

Double Fantasy is also, of course, not purely a John Lennon record. The decision to split it with Ono so completely – they would alternate songs – is the boldest play on an album that’s otherwise the slickest and most commercially focused of his career. In sharing the release, Ono and Lennon meant to create a kind of pop music diary of a relationship, or “heart play” as they called it. There was also a greater goal: to give Yoko access to the wider public.

Double Fantasy was meant to not just reinvent Lennon, the abrasive agitator turned doting dad, but also to recast Ono, who had been unfairly villainised as the woman who broke up the world’s biggest rock band. Her dissonant music was an acquired taste that had been widely mocked.

This is before digital playlists allowed us to self-edit. You could pick up the needle or fast-forward the cassette, but if you wanted your favourite Beatle’s latest release, you had to also take his wife as part of the purchase.

And the demos that inspired Lennon to call up Douglas would serve more than Double Fantasy. There would be enough material left over to deliver two more Lennon hits (“Nobody Told Me” and “I’m Stepping Out”) on 1984’s Milk and Honey and even reunite the biggest band ever.

When he got home from Cold Spring Harbor, Douglas popped the tapes into his deck and listened. The songs were raw and primitive, with Lennon accompanying himself on piano or guitar.

“They were absolutely marvellous,” says Douglas. “Incredible gems. Every one of them.”

When Lennon called the next day, the producer told him he should consider putting out the recordings as is because he was unsure he could improve them.

“I don't know if I can beat this stuff, it’s so good,” Douglas said.

Douglas met Lennon back in 1971. He was just 25 and had been logging tape at the Record Plant in Manhattan. The Beatles were finished, and Lennon was recording his second solo album, Imagine, with producer Phil Spector.

By then, according to numerous accounts, Spector, the creator of the famed “Wall of Sound,” was losing it – getting high, waving a pistol around the studio, delivering commands through a bullhorn.

John sneaked into the band room for an occasional slice of pizza – ‘Don't tell Mother,’ he’d joke, alluding to the couple’s macrobiotic diet

Lennon liked Douglas and brought him into the engineering booth. The younger man had studied at New York’s Institute of Audio Research; Ono hired him to engineer two of her solo albums. He rose swiftly from there, producing Cheap Trick, Patti Smith and Aerosmith. By then, he’d lost touch with the famous couple.

Now they were making plans for Lennon’s comeback. But they would have to take it slow.

First, Lennon charged Douglas with recruiting a band. Lennon’s main directive had been that he wanted the record to sound like the moment: New York in 1980. He needed a band made up of his contemporaries. That way, if he wanted to reference a Gene Vincent or Buddy Holly record, they’d understand the musical shorthand.

He also reminded Douglas that, for now, that band needed to maintain this code of secrecy.

“My manager got a phone call from Jack Douglas,” says guitarist Earl Slick, whose credits include David Bowie’s Young Americans and Station to Station albums. “He said he was doing a record with somebody and they wanted me to play on it but he couldn’t tell me who. We tried to get it out of him but he wasn’t going to talk.”

Ono, an adherent of numerology, asked for the birth dates and addresses for the players before approving their hiring. She also resisted rounding up Lennon’s old bandmates, including the hard-drinking pianist Nicky Hopkins, known as much for his partying as his playing with the Rolling Stones, Kinks and The Who.

“Not Nicky,” she told Douglas.

“Why?”

“Because Nicky and John are trouble together,” Ono said.

In the end, Douglas brought in only two musicians who had played on Lennon’s records: guitarist Hugh McCracken and percussionist Arthur Jenkins Jr. Bassist Tony Levin played for Peter Gabriel and Alice Cooper. Drummer Andy Newmark was on tour with Roxy Music when he got the call.

“The first thing I did, I went to soundcheck and told everybody in the band, ‘Hey, guess what, you guys. I just got called to work on John Lennon’s record’,” says Newmark. “My secrecy went out the window.”

Sidestepping familiar channels in gossipy New York, Ono hired a Boston publicist, Charles J Cohen, and told him to prepare a news release. Cohen brought in another Bostonian, photographer Roger Farrington, to document the trip from their apartment at the Dakota to the studio on 7 August, the first day of recording. Both were told that nothing could be released until the artists were ready to go public.

Rehearsals began that summer without Lennon. Douglas served as a vocal placeholder, singing as best he could. During nightly check-ins, he updated Lennon on their progress. There was also the matter of Ono’s material. She had given Douglas her demo reels the same day he came out to Cold Spring Harbour.

Beatles fans were raised on “In My Life” and “Come Together”, not the guttural shrieks and moans of the avant-garde. But by 1980, there were hints of Ono’s influence on the radio, particularly from Lene Lovich and the B-52’s. And the songs Ono brought to Double Fantasy would be a departure from her less accessible, earlier work. A song like “Kiss, Kiss, Kiss” was catchy new wave with a guitar part, says Slick, “that could have come off Station to Station.”

The dynamic with Ono did not go unnoticed. He seemed intent on using their relationship as a vehicle to reshape the traditional gender roles he had grown up with

That first day, Lennon didn’t waste time. He put a photograph of Sean on the mixing board. And as soon as the musicians were gathered, he strapped on his futuristic-looking Sardonyx guitar.

“We kind of wondered whether he’d have it together or be a little insecure or sheepish,” says Newmark. “He said, ‘Let’s get down to it and break the ice.’”

It didn’t take long. During those sessions, Lennon sang his vocal takes along with the band, banking material that would remain after Double Fantasy. He sneaked into the band room for an occasional slice of pizza – “Don't tell Mother,” he’d joke, alluding to the couple’s macrobiotic diet – and didn’t need much to restore his confidence.

A few days in, Douglas played back a vocal take of “Watching the Wheels” and Lennon responded by shouting out “Mother!”

“Yes, John,” Ono said from across the room.

“Tell the world we have a record,” Lennon said.

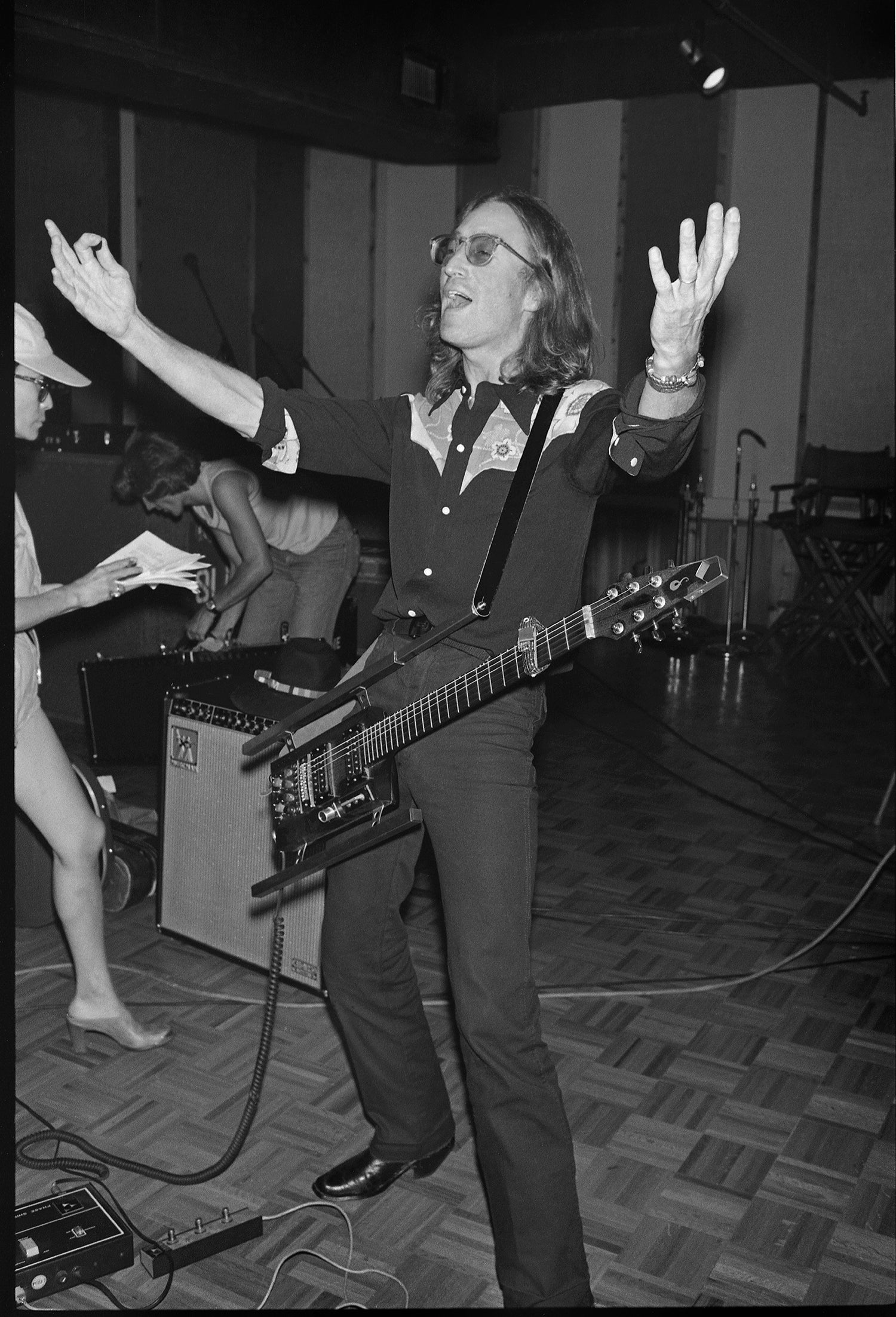

Cohen’s news release, sent out 12 August declared that Lennon and Ono were working on a new album and “a source close to the recording studio said ... it is the best of Lennon to date”. Farrington’s photo offered the public the first glimpse of Lennon in a recording studio in years. He was thin and tanned and wearing a snazzy, western shirt. Ono had her dark hair pulled back and under a cap. They wore sunglasses, staring at his Nikon without a hint of a smile.

Inside, Farrington captured Lennon strapping on his guitar, raising his arms in the air like a lion tamer, as if to urge sound out the instrument. Ono came over and, without anger but all business, instructed Farrington to follow her. “Don't photograph just John,” she said.

He captured her talking on the phone and sitting in a director’s chair behind Lennon, cigarette raised in her right hand.

Lennon’s relationship with women defined so much of his life. First there was his mother, Julia, who taught him how to play the ukulele and had a wry sense of humour but couldn’t manage parenting him as a child and entrusted his care to her sister Mimi. Then there were the women he cheated on, including his first wife, Cynthia – some of whom, he admitted in the 1980 interview with Sheff, he occasionally hit.

The dynamic with Ono did not go unnoticed. He seemed intent on using their relationship as a vehicle to reshape the traditional gender roles he had grown up with. When it came to Double Fantasy, she was an equal partner.

Which is why the “heart play”, as they called it, was both a concept and a reintroduction. Lennon and Ono’s relationship had always been shared, played out for the public.

In 1970, when the Beatles came apart, Lennon railed in Rolling Stone that they had “despised” Ono from the start and described Paul, George and Ringo as “the most bigheaded, uptight people on earth.” He also had little patience for fans who nostalgically longed for the mop tops of “She Loves You”.

In “God”, released on Lennon’s solo debut in 1970, he declared that “the dream is over” and detached himself from, among other things, magic, Buddha, Kennedy, Elvis, Jesus, Bob Dylan and The Beatles. “I just believe in me,” he sang. “Yoko and me.”

The couple were everywhere: demanding peace during their news conference “bed-ins”, taking over “The Mike Douglas Show” to jam with Chuck Berry and chat with Yippie Jerry Rubin, battling in court to keep immigration officials from deporting Lennon.

I was also expecting this rather not-very-nice woman. And instead I found her completely charming

But this unified front began to collapse in the early 1970s. At a party, according to accounts in several books, Lennon embarrassed Ono by having sex with another woman within earshot of numerous guests, and by the summer of 1973, she’d decided she needed a break. Even their separation would be a kind of public performance. When Lennon went to Los Angeles to record, Ono assigned May Pang, a 22-year-old assistant, to not only watch over him, but also to be his romantic companion.

This would be “the lost weekend that lasted 18 months,” Lennon would say later.

In LA, Lennon's drinking worsened. He blacked out and smashed up the house he was staying in. He got kicked out of the audience at a Smothers Brothers show, earning notice in the papers. His attempt to make music fizzled when he hired famed producer Spector, whose own erratic behaviour included shooting off a gun in the studio and making off with the recordings they had made.

Finally, Lennon returned to New York with Pang and agreed to make a brief appearance with Elton John at a Madison Square Garden concert on 28 November, 1974. Tony King, an Apple Records executive who was working with Lennon, heard from Ono before the show. She wanted a ticket and to go backstage.

King didn't know what to expect. But as soon as he met Ono, he knew the couple would be reunited.

“Sophisticated, very educated, very cerebral and spiritual and also quite tough,” King said of Ono. “I was also expecting this rather not-very-nice woman. And instead I found her completely charming.

“I think he had a lot of fun with May, but she wasn’t the woman of his dreams. Yoko was the woman of his dreams.”

For a time, it became easy to imagine Lennon holed up in the Dakota, covers pulled up, flipping the channel from “Barney Miller” to an old western. There were only occasional sightings of him: at a Merce Cunningham Dance Company performance with Ono; the circus with Sean; in a tux at Jimmy Carter’s inaugural.

There was even the night, in 1976, that Lennon and McCartney were at the Dakota – the two had tried to rekindle their friendship – watching Saturday Night Live when producer Lorne Michaels, as a gag, offered the Beatles $3,000 to reunite. They contemplated hopping in a cab to show up at the studio before deciding they were too tired.

“What have you been doing?” Sheff asked Lennon in the Playboy interview.

“I’ve been making bread,” Lennon said. “Because bread and babies, as every housewife knows, is a full-time job.”

The truth is, Lennon did not send out a news release announcing his semi-retirement. It just sort of happened.

Jimmy Iovine found out when he stopped by the Dakota to schedule the sessions for Lennon’s follow-up to 1974’s Walls and Bridges. In the next few years, Iovine would become famous for working with Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith and Tom Petty, and would earn millions for co-founding the Beats by Dr Dre brand. But he had started working with Lennon in the early 1970s as a 19-year-old kid at the Record Plant.

Before heading to the Dakota, Iovine had his sister pick out a teething ring at Tiffany’s, as a gift to baby Sean. When he got to the Dakota, Ono told him it was time for her husband to take a break.

“She said, ‘I’ve done some research and John needs to retire for five years and I’m going to cancel the album’,” Iovine recalls. “I said, ‘OK.’ She says, 'When's your birthday?' I told them my birthday. She goes, ‘You know, you may need to take some time off, as well.’

Iovine laughed.

“I said, ‘Yoko, I make four dollars an hour. I’ve got to get to work tomorrow.’”

While Lennon didn’t enter a recording studio during those years, he didn’t give up on music.

Years later, after he was gone, the tapes would emerge, unauthorised recordings sold in Germany or France or posted online. The demos were of varying quality, many recorded on a boombox and embellished, at most, by a primitive drum machine. But they had their charm and revealed that no matter what he was claiming, Lennon never stopped writing.

There is “Tennessee”, inspired by the playwright Tennessee Williams, dating back to the sessions Iovine was planning to book in 1975. “She is a Friend of Dorothy’s” and “Cookin’” from 1976. “Free as a Bird”, later harvested by the remaining Beatles, from 1977. “Watching the Wheels” and “Steppin’ Out” went through various changes lyrically. There were also sarcastic introductions, blistering self-critiques and, on “Nobody Told Me”, the declaration “This one’s got to be for Ringo.”

Asylum Records co-founder David Geffen told Ono he didn’t need to hear the demos, or the finished versions, before signing them. He trusted them as artists.

He also didn’t get involved in how the record would be sequenced.

One day, in the studio, Douglas, Lennon and Ono took a vote. The men agreed that the album should feature one side of Lennon and one side of Ono, but Ono disagreed. She said the tracks had to alternate; ultimately the producer and her husband acquiesced.

“I think he felt that if everything of his was on one side and everything of hers was on the other, nobody would listen to the other side,” says Geffen. “And that’s not what he wanted.”

Ono and Lennon would create their dialogue by pairing songs by theme: Love (“Dear Yoko”, “I’m Your Angel”), conflict (“I’m Losing You”, “I’m Moving On”), and facing adulthood (”Hard Times Are Over”, “Watching the Wheels”). They each delivered a song centred around their soon-to-be-five-year-old boy, Sean (“Beautiful Boys”, “Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)”).

They wanted Double Fantasy to sell – they would tape the weekly Billboard chart to their bedroom door – but Lennon also wanted to deliver a message. The album had to update his sound and his image.

“This isn’t an album we want to sell to kids,” he told Douglas. “I’m going to be 40. This is an album we’re going to sell to the people who have been through the wringer of the ’60s and the ’70s. It's about a guy who’s married, whose life has changed. He’s cleaned up his act. And that’s what I want to say.”

Double Fantasy came out the third Monday in November. The reviews were mixed and sales were decent, if sluggish. At one point, Ono called Geffen with a plan to move more copies.

“She said, ‘I want you to go out and buy records at every record store,’” says Geffen. “She thought it could be operated, which it really can’t.”

But Lennon was inspired. He called Douglas to work on an additional song of Ono’s that he felt could be a hit, “Walking on Thin Ice.” The song would feature a searing guitar solo from Lennon, playing his 1958 black Rickenbacker 325 guitar. He hadn’t picked it up since a Beatles session in the mid-60s.

On 8 December, Lennon and Douglas finished mixing the song and agreed to meet, as usual, for breakfast the next day before getting back to work. There were big plans. They wanted to get the band back together to finish the tracks left over from Double Fantasy. There was talk of a tour. Lennon had even written drummer Jim Keltner, a longtime friend and collaborator, that he was thinking of making a record with “just the boys”.

That dream ended just before 11 o’clock that night, when Mark David Chapman, a 25-year-old former security guard who had earlier that day asked for and received an autograph on his copy of Double Fantasy from Lennon, shot and killed him as he returned home to the Dakota.

Double Fantasy immediately rose to No 1 in both the United States and United Kingdom. It would go on to win the 1981 album of the year Grammy and sell 3 million copies, the most for any Lennon solo album. In 1981, “Walking on Thin Ice” would be Ono’s biggest hit, cracking the top 40.

Ono struggled in the aftermath. There were death threats and there was Sean, a young boy without a father. There was also a slew of thefts, with one longtime assistant arrested for taking photographs, letters and Lennon’s diaries. That assistant, Frederick Seaman, would write a scathing book accusing Ono of drug use and brainwashing Lennon. There would be others, from infamous biographer Albert Goldman to Ono’s onetime tarot-card reader, John Green.

For a time, Ono fell out with Geffen and refused to give Douglas production credit or royalties from Milk and Honey. Douglas sued and won a $2.5m court judgment in 1984.

And Douglas did his own disappearing act, slipping into a decade-long heroin addiction. Years later, he would re-emerge, repair his relationship with Ono and produce with her a new, stripped down mix of Double Fantasy.

The demo tapes Lennon stuffed in the envelope would ultimately lead to an unlikely reunion. On a freezing winter night in 1994, Paul McCartney visited Ono and Sean at the Dakota and they played him a song on one of Lennon’s demo tapes, “Free as a Bird”.

The next month, the remaining Beatles met in the studio and, as Starr put it, imagined John had “gone for lunch”. McCartney sang harmonies with his old friend, Harrison provided his distinctive slide guitar and Starr’s steady beat filled out the sound. “Free as a Bird”, released in 1995, became the first new Beatles single since their breakup in 1970. And the figure who brought them together this time was Yoko Ono.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments