Watch the throne: How hip hop royalty are facing up to their waning powers

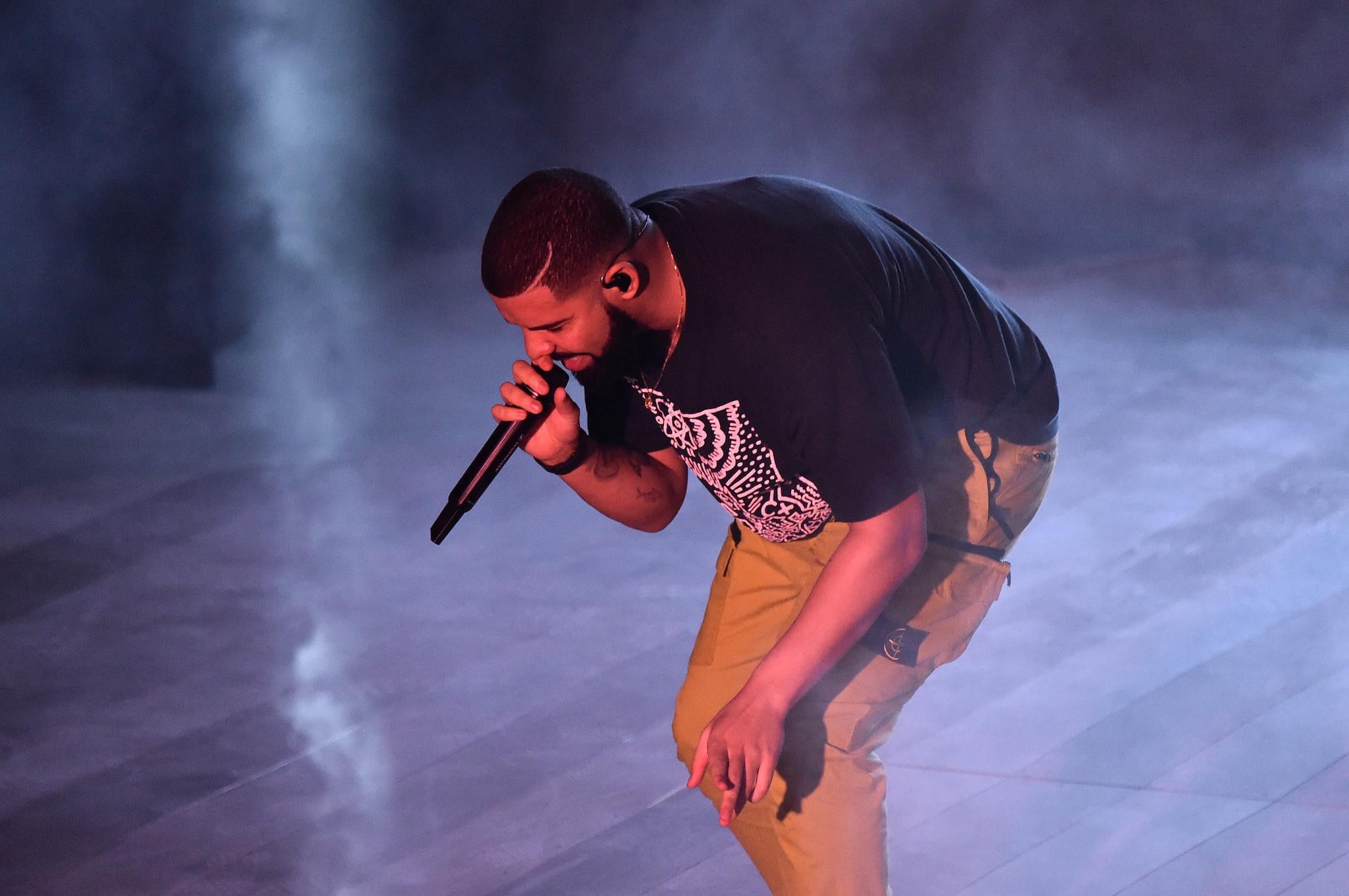

Kanye West, Jay-Z, Drake and J Cole are all using their music to address the question: what does a genre-dominating rapper do when the genre moves on?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hip hop has long been about superheroes, and there are few things more jarring than watching a superhero’s powers begin to fade.

The superstars of earlier hip hop generations typically lived their post-peak careers just out of the limelight. If they were grappling with diminished influence, it rarely showed or shaped their public narrative.

They disappeared into the executive suite (Dr Dre), or they became actors (LL Cool J, Ice-T), or they settled into a comfortable late-career plateau that mostly sated old fans while not really striving for new ones (Snoop Dogg).

But then hip hop started growing exponentially: it minted more durable, truly multigenerational stars with greater staying power; at the same time, it was revving up the engine on the lower end, welcoming more and more young artists into the fold.

Now these post-prime stars are working out their post-prime issues in public, on record, for all to hear

That meant that while the market expanded, more artists were competing for prime share, forcing those on top to learn how to navigate new territory: as still popular, almost dominant performers who are staring down their role as elders.

Now these post-prime stars – or those on the verge of reaching their tipping point – are working out their post-prime issues in public, on record, for all to hear.

Over the past three months, four superstars have released albums that assess, from different angles, what a genre-dominating rapper does when the genre is beginning to move on.

Kanye West’s ye (as well as his collaborations with others); Drake’s Scorpion; J Cole’s KOD; and Jay-Z’s Everything Is Love, which he and Beyoncé put out as the Carters.

Their reckonings take many forms. For West, it is the acknowledgement of the frailty of his mental health. For Cole, it is a finger-wagging semi-scolding of the younger generation. For Jay-Z, it is a calm acceptance of his diminished public stature.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

And for Drake – who now feels like the youngest member of this older umbrella generation, but until recently was the oldest member of the younger upstarts – it is navigating the tension inherent in moving from student to teacher, and realising your teachers were no better than you all along.

Of these, West’s path is the most radical in terms of how it engages with the spectre of obsolescence. On “What Would Meek Do?” from Pusha-T’s “Daytona”, West raps about how he is viewed by septics: “You see, he been out of touch, he cannot relate / His hallway too long, bitch too bad.”

But West’s flaws are real, too, and he now publicly discusses his health struggles. “Hospital band a hundred bands,” he raps on “Yikes”, referring to his hospitalisation in late 2016 for exhaustion. “You know I’m sensitive, I got a gentle mental / Everytime something happen they want me sent to mental,” he bemoans on “Wouldn’t Leave”.

Here is the hero heading towards twilight, or perhaps reframing what it means to be a public hero at all. “That’s my superpower!” West barks at the end of “Yikes”, speaking about his bipolar disorder diagnosis. “Ain’t no disability!”

For Jay-Z, the acceptance of his recession from his peak began with last year’s 4:44, a moody, raw album from an artist who had long been self-examining, but rarely made it central to his public persona. But marital strife has a way of undoing hubris, and Jay-Z’s public arc has lately been defined by a kind of deflation. When he has performed alongside his wife, as during her acclaimed Coachella set, he has seemed small.

He has been the subject of several needling memes, the internet’s tool of casual disrespect, making him an avatar of befuddlement or physical awkwardness. He knows what the kids are saying about him: “Online they call me ‘dad’ kiddingly,” he raps on “Heard About Us”.

Throughout Everything Is Love, he is the less present force – the less present rapper, even. It is charming, as ever, to hear him rap about being in awe of his wife, especially when addressing his own shortcomings: “My first time in the ocean went exactly as you’d expect / Meanwhile you going hard, jumping off the top deck / A leap of faith, I knew I was up next.”

A decade ago, a rap superstar would have been unlikely to rap about perceived weaknesses of any kind, certainly of the sort that come with age. (Eminem is, in this way, an outlier, much as he is in a outlier in many others; weakness has been his gasoline since the beginning of his career).

But as life has thrust him away from rap’s centre, Jay-Z is provocatively reimagining the genre’s boundaries and expiration date.

Learning that your emperor has no clothes is an emotionally taxing experience, so it is unsurprising that Drake has delved into that territory so effectively. On “Emotionless”, he raps, “Meeting all my heroes like seeing how magic works / The people I looked up to are going from bad to worse / Their actions out of character even when they rehearse.”

By contrast, Cole focuses his gaze downward, aiming a been-there-rapped-that talking-to at the SoundCloud rap generation that made a sport of mocking him. On “1985 (Intro to ‘The Fall Off’)”, he addresses them from the perspective of a big brother who’s seen it all:

Congrats ‘cause you made it out your mama’s house

I hope you make enough to buy your mom a house

I see your watch icy and your whip foreign

I got some good advice, never quit touring

Collectively these artists represent three generations of hip-hop superstardom, and there are significant familial bonds among them – West was signed to Jay-Z’s old label, Roc-A-Fella; Cole is signed to Jay-Z’s Roc Nation imprint; Drake has collaborated with West and Jay-Z; Cole has toured with Drake; and so on.

Though all of them engage with fatherhood in their music, what truly marks this phase of their careers is the way they interact with the generations above and below them.

Sometimes these intergenerational tensions are expressed through music, not words. Drake’s “8 Out of 10” sounds like a musical slight towards West, invoking West’s horn-thick early production. (And “Talk Up”, his collaboration with Jay-Z, feels pointed as well.)

On the title track from “KOD”, Cole – who also took on West a couple of years ago, on “False Prophets” – embraces the opposite approach, rapping in terse SoundCloud-rap patterns, as if to prove a point.

And sometimes the parent spanks the child with words. On “No Mistakes”, West seemingly aims some shots at Drake, an inheritor who is now a peer: “Too close to snipe you / Truth told, I like you.”

On “Boss”, Jay-Z – an owner of his own streaming service and management company – laments those who would “rather work for the man than to work with me”. On “Brackets”, Cole is mindful of the younger artists “hating on me, I ain’t used to that / Know a couple people wanna shoot for that / I say ‘No, no, no, chill, it ain’t no need for that.'”

Of the four artists, Cole has been the most thoughtful in how he wields his power. Following his album’s release, he wrangled the 17-year-old rising star Lil Pump – one of the rapscallions who made Cole’s name a punch line – for an hour-long video interview.

It is a remarkable exercise in empathy, and a genuine attempt at bridge-building. Cole understands that hip hop’s intergenerational battles can be as poisonous as the ones between the genre and outsiders, and made the humane choice to reach out to and embrace Lil Pump rather than scorn or dismiss him.

That Cole then modelled maturity and vulnerability for him – talking about his difficult relationship with his stepfather, advocating for financial responsibility, admitting his own stubbornness about hip hop’s shifting tides – was startling and impressive.

In those moments, Lil Pump went from a pest to a peer, and Cole from an abstraction to a real human. A true superhero does not need a perch of any kind.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments