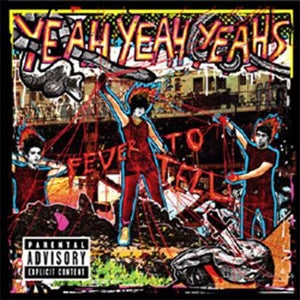

Karen O, self-destruction and rubber bones: Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Fever to Tell, 20 years on

As ‘Fever to Tell’ celebrates its second decade, Mark Beaumont looks back at the glitter-stained, tequila-soaked origins of Yeah Yeah Yeah’s iconic debut record

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Landing clean out of the blue, in a shockwave of cheek glitter and sweat, she was a very postmodern Gotham superhero. When mild-mannered film student and acoustic singer-songwriter Karen Ohm donned her endless array of outlandish outfits and drank her special potion – margaritas, champagne, tequila, fan beers – she transformed into Karen O, the art punk chaos queen of the Noughties New York scene.

As the singer of Yeah Yeah Yeahs – the Brooklyn trio comprising Karen O, guitarist Nick Zinner and drummer Brian Chase whose iconic, million-selling debut album Fever to Tell was released 20 years ago on 29 April – Karen O was formidable. She could shape-shift in an instant, morphing between a she-wolf howl and pussycat purr. She could swallow virtually an entire microphone while still singing; spew beer from the height of any lighting rig; and mesmerise indie fans in their thousands with her incredible concoction of celebratory raunch rock, fun-time innocence and open-hearted fragility. Most vital of all, with one lick of liquor, she grew rubber bones.

“My insanity onstage had been escalating and the more I hurt myself, the more the crowd enjoyed it,” Karen O told Billboard in 2013. “I was like Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler.” She found that performing drunk imbued her with a looseness that prevented injury whenever she fell – and she fell a lot. She thinks it was the alcohol that saved her life when on 9 October in 2003 at Sydney’s Metro Theatre, the O show almost reached a gruesome, premature end.

“During the song ‘Rich’ I was on the edge of the stage, sort of draped over the monitor with my legs in the air,” she told Lizzie Goodman for the scene’s renowned oral history Meet Me in the Bathroom (2017). “And I was really drunk. I flipped off headfirst, hit the guardrail and landed on my back. Then the monitor fell on my head…The only thing that saved me from breaking my neck and my spine was the fact that I was so wasted, I was limber. I fell off like a wet noodle.”

While their New York peers such as The Strokes and Interpol took great pains to look unflappably cool onstage, Yeah Yeah Yeahs were undoubtedly the most heart-in-mouth live experience of the age. The sort of exhilarating spectacle it’s almost impossible to capture on a studio recording. Fever to Tell, though, did just that. Garage art rackets “Y Control”, “Tick” and “Pin” – sounded as if they were distilled from the sweat sloughing off a Williamsburg basement club ceiling. Sleazy blues rockers “Black Tongue”, “Cold Light” and “Date With the Night” – a song Karen O described as “seeping with sex” – gave lascivious voice to New York’s post-millennial lusts. Her inherent hotline-to-the-heart rang out on the more fragile “Modern Romance” and “Maps”. The latter was a visceral love song addressed to her boyfriend Angus Andrew of Liars. It became the album’s tear-sodden calling card.

“At the time it was really hectic with us touring and my boyfriend being away with his band,” Karen O told Spin in 2004. “The line ‘They don’t love you like I love you’ was like, ‘Why are you over there with them when you should be with me?’ It’s about missing someone.” Later, she told Rolling Stone that her candour had shocked even herself. “I exposed myself so much with that song,” she later told Rolling Stone.

Fever to Tell certainly shocked anyone that had watched Karen O’s rise through New York City’s thriving ranks. A reserved and studious Jersey girl, she’d originally met Chase at Oberlin arts college in Ohio, bonding despite in-built musical differences. He was a jazz fiend who wrote classical pieces; she was a stan for The John Spencer Blues Explosion. To get herself through Ohio’s stultifying winters, Karen O decided to learn guitar and began writing songs on a karaoke machine: “The ultimate in lo-fi.”

In 2000, seeking less spirit-sapping environs, she relocated to NYU to study film – and knee-slide across the dancefloors of the city’s burgeoning alt-rock club scene. It was at grungy East Village haunt, the Mars Bar, that she first met Zinner, a freak-haired photographer and guitarist who seemed to be in every warehouse art band in New York. “All her songs were really morbid,” he told NME in 2003, which he saw as a challenge: “These are great, but I can make them better.” The first time they played together, Zinner instantly sensed the magic. “I felt it,” he told Goodman. “Just woooooshhhh. Immediate connection.”

Together they became Unitard, a gentle folk duo playing what Zinner called “great, haunting ballads…very Paris, Texas”. They began making waves in the anti-folk scene emerging from the Sidewalk Café, which also produced The Moldy Peaches. But such a combo could never contain the natural trouble-making exuberance that went on to make Karen O a literally intoxicating presence on the scene. Zinner called her a party-in-a-bag. “She had this infectious, super-wild, didn’t-give-a-f***, awesome, fun, silly thing,” he said. “Unitard was super dark but that lightness, that silliness, was inside us and Karen was an expert in bringing it out and embodying it. We really needed that and New York needed that too.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

One night in Zinner’s loft, playing around with a drum machine, Karen Ohm drank her superhero potion – rum fruit cocktails, and plenty of them – and became Karen O. “We drank brass monkeys and literally in two hours wrote four songs, and two or three of them were on our first EP.” The first song they wrote was “Bang”. As a f***, son, you suck,” that febrile, clatter punk debut track declared, shaking awake the sparse crowd lucky enough to catch Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ first show at New York’s Mercury Lounge in 2000, fifth on the bill to The White Stripes. And of the city’s swarm of new post-Strokes sounds, it was “Bang” and its parent Yeah Yeah Yeahs EP that blew up biggest.

By the summer of 2001, NME’s We Love NY issue and The Strokes’ first album Is This It? had made the New York scene an international phenomenon. If the cult cool of the scene was captured by Julian Casablancas and his roughed-up Rat Pack staring out from a monochrome photo frame, collapsed around an East Village bar in slept-in suit jackets, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs EP encapsulated all of the wild colour coming along in their wake. “Mystery Girl” and “Art Star” spoke to the city’s art punk pulse, “Our Time” to its place as the wellspring of the 21st Century zeitgeist. As the EP – eventually voted the second best single of 2001 by NME – and word of Karen O’s beer-guzzling, hard-partying onstage antics filtered through New York, Yeah Yeah Yeahs quickly became a sensation.

“There was just such urgency and self-destruction,” Karen O told Goodman, “the need for release, hedonism”. YYYs gladly fulfilled it. They tore up NYC fashion parties, wrecked the backstage area at SXSW 2002 and, though Karen O claims to have no memory of the event, allegedly shoved Courtney Love into a catering table when she turned up backstage unannounced to hob-nob with the band. “We set out to conquer,” she recalled, “with the invincibility of rebel youth times a hundred, fuelled by tequila and really, really naughty prankster behaviour [plus] all those people trying to find us and woo us.”

Among so many archly wasted male peers, Karen O was adopted as a champion of forthright feminism, unashamedly indulging desire, despair and delight in equal measure. “A lot of girls, myself included, finally felt we had someone onstage we could relate to,” her designer friend Christian Joy told Goodman. “Someone who did not give a f*** in the same way we did and didn’t mind being dirty and unsexy and was just being herself and was not a dude.” Joy designed all of the outfits, which were key to Karen O’s onstage persona. No two ever remotely the same: ruined cheerleader dresses, psychedelic catsuits, new age sci-fi work-out garb. They were often put together at very short notice, too. “I’d call her up the day before a shoot and say, ‘I need something tomorrow!’” Karen O told NME in 2003. “She’ll burn the midnight oil, but the next day, I’ll put it on and it’ll be really short or my boobs will just be popping out. I guess it’s her way of venting frustrations.”

The band chose a friend of theirs to produce their debut album – their tour manager David Sitek, later of rock group TV on the Radio but back then an unknown. “They said I should record their new record,” he told Spin in 2007. “I said ‘I dunno, you guys have a lot of momentum. I might screw it up.’” But by the time the band came to record it the industry scrum to sign them, coupled with the “overwhelming” fanaticism and physical toll of living up to the fervid expectations they had set for their live performances, had caught up with them. Karen O later likened the experience to feeling like the celluloid cowboy knocked from his horse “but his foot is still on the stirrup and he’s just being dragged by this f***ing mustang”. Having rushed through much of the record in a day or two, she insisted that the band cancel a scheduled tour, including an appearance at Reading & Leeds 2002, in order to concentrate on finishing the album. Organisers offered to triple their fee, but no dice.

“I was at the tipping point,” she told Goodman, fearing burn-out at such a pace. “I definitely felt like I was on the verge of a meltdown… The record was more important than dragging ourselves around on the road. And for me personally, just like health-wise.” She soon moved out of the city to the New Jersey farmlands with Andrew, then later to LA, her departure signifying the beginning of the end of the New York scene. “We had to survive that insanely precarious razor’s edge that you walk on as a band that’s hyped so young, trying not to get sliced down the middle.”

The extra time on Fever to Tell was well spent. Though YYYs would go on to make more consistent, refined albums – Show Your Bones (2006); It’s Blitz! (2009) – and attract a new generation of electro-modernist fans with last year’s Cool it Down, their debut remains one of the most vibrant burst-from-the-underground records of all time. Despite glowing initial press notices, still it is perhaps no surprise that album sales tripled upon the release of “Maps” as a single. After all, that moment Karen O’s anguished trills of the title collide with Zinner’s highway pile-up of a guitar solo is among the most heart-stopping in pop.

“I’m going to rewrite history right here,” Karen O told Goodman of the lyrics “they don’t love you like I love you”, which she had lifted from an old email love letter. “I wrote it with a quill. It was a feather quill, written in blood,” she insisted instead. “It might as well have been.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments