World Goth Day: An anatomy of melancholy from Goya and Edgar Allan Poe to Bauhaus and Tim Burton

Post-punk subculture still thriving as inclusive movement and traces origins back to Romantic literature, architecture and painting

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.World Goth Day takes place on 22 May, an occasion for the pale and morbidly-inclined to emerge squinting into the sunlight to celebrate their individuality.

Goths in black hoodies, band t-shirts, panda eye shadow and even Victorian funeral weeds and moderate fetish wear are a common sight in market town centres across the country these days. Most people now understand that the look is nothing to be intimidated by, not necessarily a symptom of depression and much more than “just a phase” that teenagers drawn to occultism and pagan symbols will grow out of.

Wearing black is actually a clear indication of a melancholic personality type as old as the Elizabethan malcontent and Goth turns out to be a healthily inclusive tribal movement that shuns prescribed gender expectations and unrealistic physical ideals, placing an unfashionable premium on reading. All reasons its adherents, predominantly middle class and white, deserve respect rather than ridicule.

Primarily an offshoot of the punk era – although there were pre-1977 proto-Goths such as Screaming Lord Sutch and Alice Cooper and plenty of rockabilly groups toying with graveyard motifs – bands like The Damned, Siouxsie and the Banshees and Misfits all adopted Halloween dressing-up box aesthetics for shock effect.

The first Goth song proper is generally agreed to be “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” by Bauhaus, a nine-minute ode to the Hungarian actor so famous for playing Dracula that he was buried in his costume cape in 1956. The piece is known to many from its ominous use at the beginning of The Hunger (1983), Tony Scott’s vampire movie starring Catherine Deneuve and David Bowie.

Subsequent bands took the style in different directions throughout the 1980s, from the scary antics of garage rockers The Birthday Party and The Cramps to the gloom pop of The Sisters of Mercy and The Cure. Killing Joke and Depeche Mode led matters in an industrial direction culminating in Nine Inch Nails and the cybergoth rave scene, while others pushed on into dark metal territory, hence Cradle of Filth and Marilyn Manson.

Gliding swiftly past My Chemical Romance, Panic! At The Disco and the genuinely horrifying world of Emily the Strange merchandise, a track like Jenny Hval’s dreamy “Female Vampire” from 2016 shows what can still be achieved within the confines of the genre.

Before the punks, cinema had long catered to the same taste for the macabre, from Universal’s monster pantheon of the 1930s to the atomic age American B-movies of the 1950s, Hammer Horror, Italian giallo and the suburban slasher films of the 1970s. Tracks like “I Was a Teenage Werewolf” by The Cramps or “Night of the Living Dead” by Misfits directly referenced the key films that informed these Goth taste-makers.

Tim Burton subsequently picked up the megaphone, himself hugely influenced by the shlock disasterpieces of Ed Wood and Roger Corman’s series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations starring Vincent Price. His early films, notably Beetlejuice (1988), Edward Scissorhands (1991) and particularly The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), are all Goth favourites, their melancholy protagonists obsessed by their own outsider status, a mood he made the subject of two Batman features.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Neil Gaiman’s Sandman (1989-96) and James O’Barr’s The Crow (1989-) graphic novels are required reading. The central characters of Morpheus, the Lord of Dreams, in the former and undead avenger Eric Draven in the latter were both modelled on the gaunt figure and pronounced cheekbones of Peter Murphy, frontman of Bauhuas, AKA “the Godfather of Goth”.

There’s room for humour in all of this, incidentally. Goths are drawn to the morosely funny artwork of Edward Gorey and Charles Addams, the TV and film spin-offs of the latter’s New Yorker cartoons, re-runs of The Munsters (1964-66) and novelty records like Bobby “Boris” Pickett’s “Monster Mash”. Even Nick Cave’s The Birthday Party, whose heroin-fuelled gigs earned notoriety at the turn of the 1980s, sent themselves up riotously on “Release the Bats”.

Or how about Jonathan Richman’s affectionate spoof “Vampire Girl”?: “Does she cook beans? Does she cook rice? Is she into ritual sacrifice?”

Prior to its late blooming in 20th-century pop culture, the Gothic really emerged as an aesthetic in the Romantic literature, architecture and painting of the 18th and 19th century.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) is, obviously, the ur-text of modern Goth but the subculture’s roots go back further to the stories of Robert Louis Stevenson, Poe and Sheridan LeFanu and the “haunted summer” of 1816 when Mary Shelley conceived the central idea for Frankenstein during an evening of ghost story recitals on Lake Geneva with her poet husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron and Dr John Polidari, whose own tale that stormy night, “The Vampyre”, would directly influence Stoker.

Even before this, there was Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1775), William Beckford’s Vathek (1786) and the supernatural mystery novels of Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823), works satirised by Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey (1817).

Walpole, an MP and the son of prime minister Sir Robert Walpole, was so enraptured with the Gothic that he had his own mansion built in order to live it, a lavish vanilla Viennetta of battlements and spires known as Strawberry Hill in Twickenham. His influence sparked a fashion that continued throughout the following century when many of London’s most recognisable landmarks, from the Palace of Westminster, London Bridge and St Pancras Station, were constructed.

Walpole’s taste was neo-Gothic, strictly speaking, drawing on an architectural movement that first flourished in continental Europe between the 12th and 16th centuries, characterised by cavernous masonry, rib vaults, pointed archways and stained glass. The Basilica of St Denis and Chartres Cathedral in Paris are two fine surviving examples.

None of this has anything much to do with the historical Goths, by the way. These were the East Germanic people, divided into Visigoths and Ostrogoths, who fought the might of the Roman Empire. The term “Gothic” has been applied to architecture retroactively, thought to be because of the melancholy connotations associated with these tribes as harbingers of darkness for the Romans, responsible for the sun setting on the early superpower’s dominance of Western Europe.

There was no coherent Gothic movement in painting per se but the German landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), a specialist in misty ruins and lone figures adrift in the sublime, certainly fits the bill: “I have to stay alone in order to fully contemplate and feel nature.”

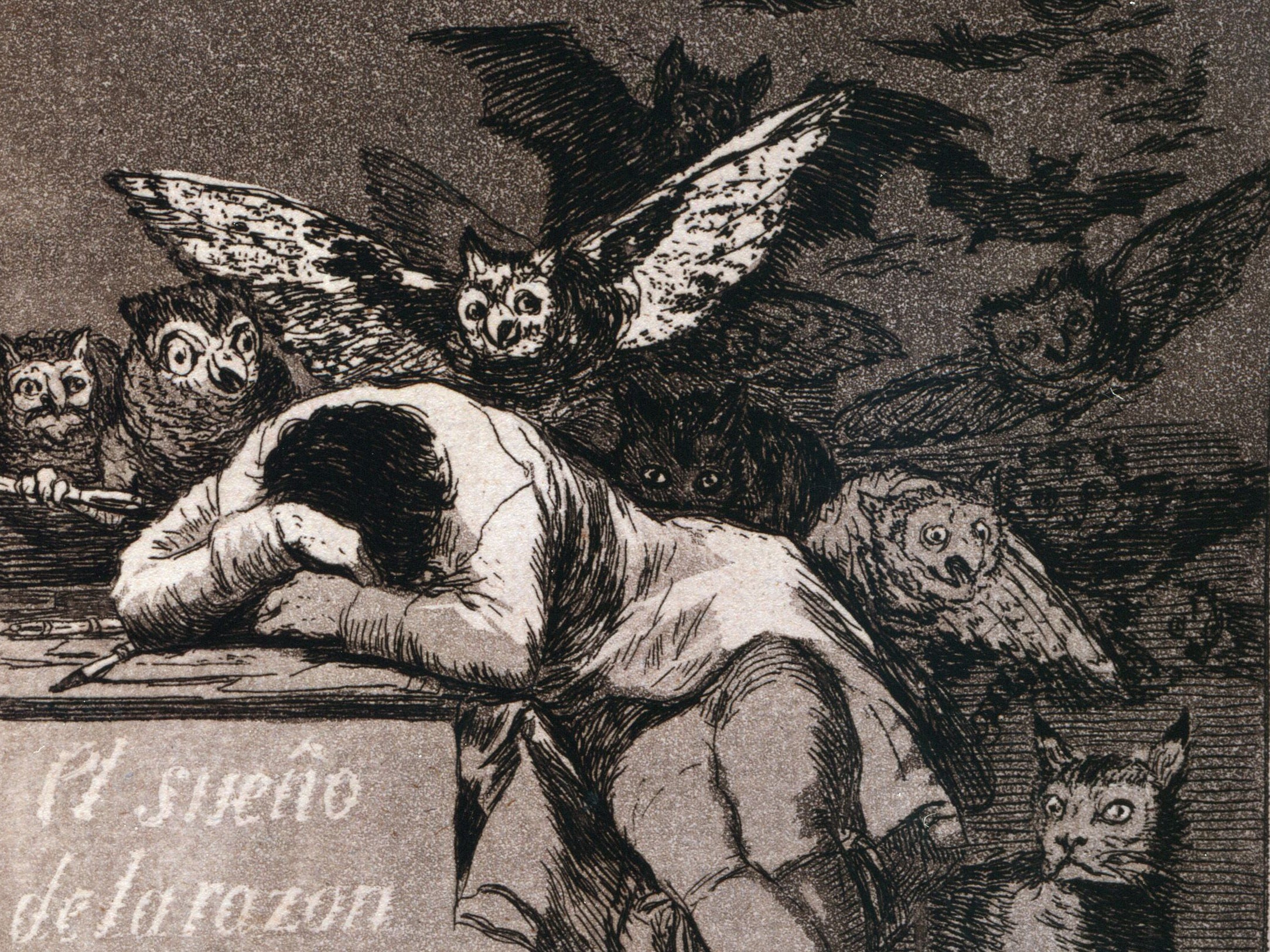

Other artists who exorcised their personal demons on canvas long before there was a name for it include Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), best known for his disturbing and erotic “The Nightmare” (1781), and Francisco Goya (1746-1828), whose etching “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” (1799) externalises the inner torment many feel but struggle to express.

A style as deathless as its heroes, Goth is an entirely positive movement because it enables its followers to find solace in the like-minded, who are clearly demarcated by their outfits, and because the genre is loaded with stone-cold bangers like “This Corrosion” by The Sisters of Mercy.

And everyone looks good in black. Or, as Dwight Pullen put it: “You really look sharp wearing sunglasses after dark.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments