The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

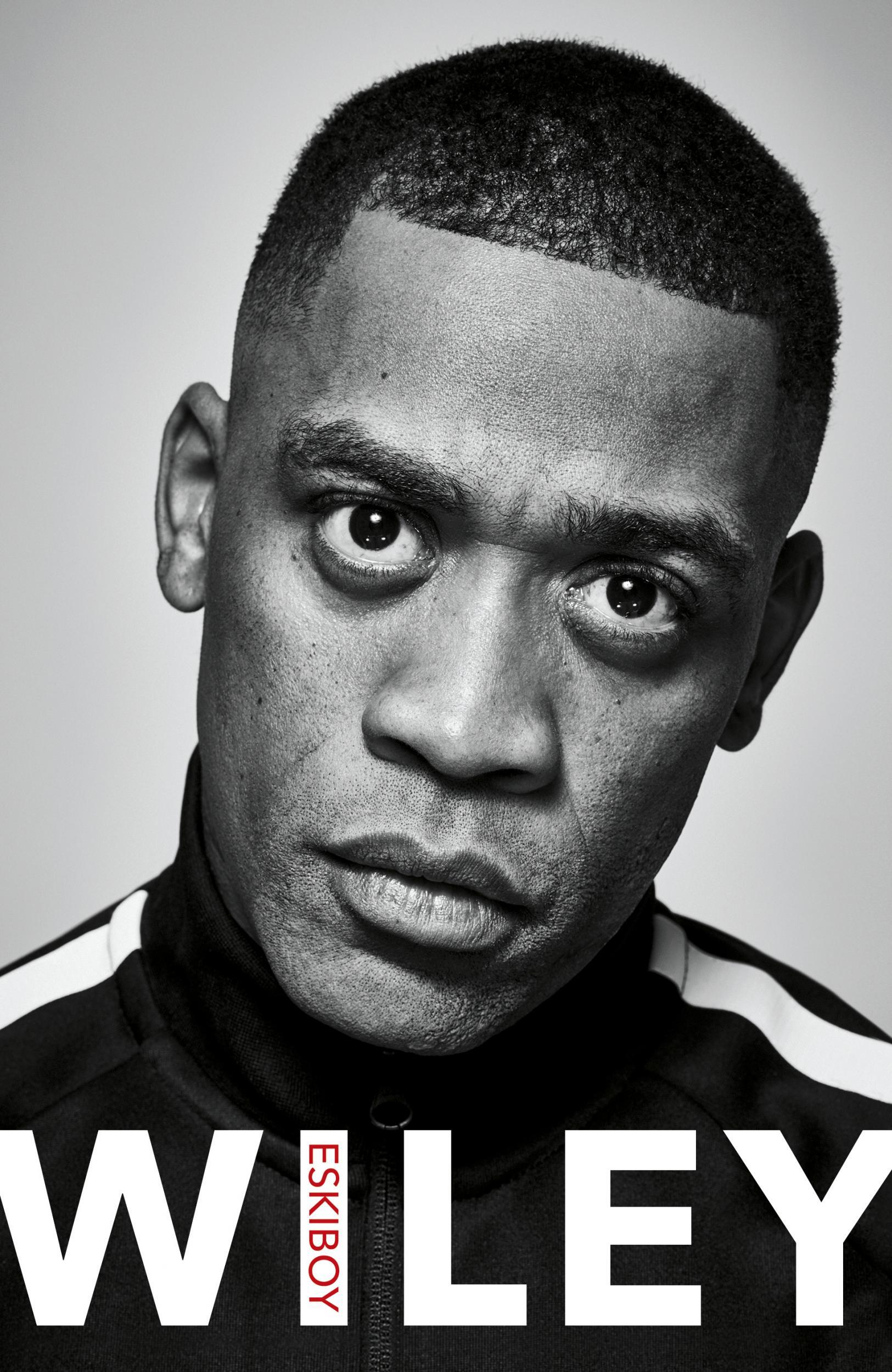

Wiley: Read an extract from the Godfather of Grime's autobiography 'Eskiboy'

In this exclusive extract, Wiley reflects on the moment he realised he could make music without industry support

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.14. Dubplate

My dad is all about music. That’s his thing. And that’s what’s so unusual about us lot, as well. Our parents loved music, and our parents played music, and our parents all knew each other through music. It was kind of what connected everyone.

Their generation passed on a lot to our generation. For me at least, I’m doing what I’m doing because of them. He gave me the gift. They’ve paved the way, and we’ve reaped the rewards for their work. Maybe we’ve gone further because now it’s easier to become someone with less work, do you know what I mean? It’s not about playing instruments and singing. You can make a little tune and put it out yourself and have people pay attention.

We owe a debt to them, though. Not only our parents, but all the seventies, eighties reggae people, Tippa Irie, Smiley Culture, whoever, bro. These guys. We grew up listening to a lot of dub tracks. Dub was kind of what made us who we are.

My dad always used to say, ‘I’m a roots and culture man. Anything that sounds good to my ears and my heart.’ When they started out they all used to go to youth clubs. Everyone would come from different

areas – Bow, Poplar, wherever – and try and get on the mic. Everyone knew who was good and everyone knew who was up-and-coming.

But you had to have bars. If you asked for the mic and you didn’t have any talent, you wouldn’t get the mic again. End of. The good people would get the rewinds, they’d get noticed. That’s how it was with dancehall, with ragga and with reggae, back in the day.

The whole confrontation thing was exactly the same, too. Back then, if you jump on the mic, you’ve got to prove who you are. You couldn’t talk nonsense, or just make something up. The bars that you were spitting were actually true. You had stories. That was really the start of MCing, or MCing as we understood it to be.

That culture also fed into jungle. Jungle knowledge is important.

Jungle was kind of the first music that we felt could be ours, or that we could be a part of. It was all happening in the early nineties, or up to 1995, 1996. I had just moved back to London with my dad, so I was around thirteen, fourteen, fifteen. A lot of people were into it. D Double E, Terror Danjah, Footsie, Slimzee. Getting decks, getting on the radio.

Slimzee and me went to the same school and we’d get the same bus home. I knew he DJed, and around the time I was getting into music myself. I remember having a conversation with someone else from school about him.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

They bigged him up. And it turned out he lived across the road from me.

So one day, I went round to his house and asked if I could see his decks. He had all the hardcore selection already. And that was the music that was like clubbed into my brain at the time, fully. So I was gassed. I was like, ‘Oh my god, I know that ragga tune!’ I was really excited about any jungle tracks which had a little ragga sample or a hip hop sample. I used to love that, and had a lot of it.

Back then, it was all about the scene. There was a proper scene, and we were all trying to get into it. But we were all kids, really. We loved it, and they obviously showed appreciation to us for loving it, but we weren’t really in it. Jungle kept it tight. Like they didn’t care about major labels, they don’t jump up for man, they weren’t gassed about anything. They were feet-on-the-floor people. You can’t just go in jungle and bust one tune then go clear. It didn’t really work like that. You had to keep going and keep going. I respected them for that. Most other scenes are really disposable.

That was the start, in a way. It was the first time I realised that we could do this. We didn’t really need anybody else. We had decks, we had the mic, we had the radio. Didn’t need to wait for anyone, impress anyone, push anyone. Just us.

Extracted from Eskiboy by Wiley, out now from William Heinemann - available here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments