The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Why the 27 club is a myth: Jimi Hendrix and Amy Winehouse may be members but that doesn't make it real

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What do Otis Redding, Gram Parsons, Nick Drake, Jimmy McCulloch, James Ramey (aka Baby Huey), Bryan Osper, and Jon Guthrie have in common?

What about Tim Buckley, Gregory Herbert, Zenon de Fleur, Nick Babeu, Shannon Hoon, Beverly Kenney, and Bobby Bloom?

And Alan Wilson, Jesse Belvin, Rudy Lewis, Gary Thain, Kristen Pfaff, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Pete de Freitas, Raymond “Freaky Tah” Rogers, Helmut Köllen, and Linda Jones?

In a population of dead musicians spanning seven decades from 1950 to 2010 for which an accurate age of death could be identified (n=11,054), 1.2% (n=128) died at 26, 1.4% (n=153) died at 28 and 1.3% (n=144) died at 27.

Age 56 had the highest frequency of deaths (2.2%; n=239). Notables dying at this age include Eddie Rabbitt, Tammy Wynette, Mimi Farina, Johnny Ramone, Chris LeDoux, Vandy “Smokey” Hampton, and Charles “Baby” Tate. Below is a visual representation of the percentages of deaths at each age.

So why isn’t there a 56 Club or a 28 Club? Is it because Brian Jones (drowning), Jimi Hendrix (aspirated vomitus from barbiturate overdose), Janis Joplin (heroin overdose), Jim Morrison (drug-induced heart attack), Kurt Cobain (suicide by gunshot) and Amy Winehouse (alcohol poisoning) all died aged 27?

All were tortured souls who reached pop stardom and died tragically at their zenith. Perhaps we need to consider a change of name for this group – from the 27 Club to “The Tragic Six” or “The Tragic Seven” if we include Robert Johnson?

There are many more musicians who died at the age of 27 than these six (or seven) – there were another 137 in my population including the very notable musicians named earlier. So …

Jimi Hendrix died at 27

What percentage of pop musicians needs to die at age 27 to support the existence of the 27 Club?

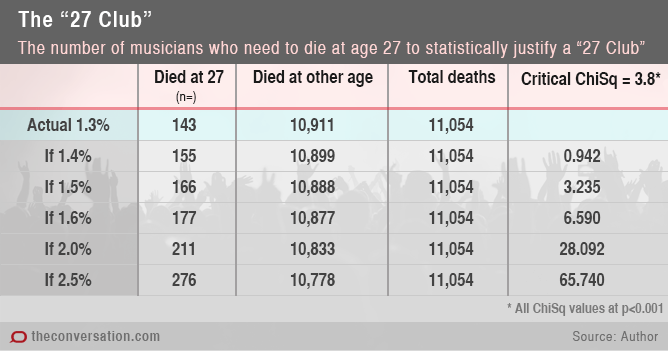

Here is a thought exercise we can submit to statistical scrutiny to answer the question: how many pop musicians need to die at the age of 27 to justify the notion of a 27 Club. The actual proportion is 1.3%. Do we need 1.4%, 1.5%, 1.6%, 2% or 2.5% of popular musicians to die at the age of 27 to conclude that age 27 is associated with a higher risk of death than other ages?

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

We can test this question using a single sample ChiSq test, which assesses whether there is a significant difference between the expected frequencies (i.e., specified proportions of deaths at 27) and observed frequency of actual deaths.

As the table shows, a minimum of 1.5% to 1.6% of deaths in the population need to occur at age 27 to “justify” the 27 Club statistically. It is at this number that the ChiSq value exceeds the critical ChiSq. In other words, the actual number of deaths is significantly less than the number that would need to die at 27 if the 27 Club hypothesis were correct based on numbers alone.

But even at 1.6% of deaths occurring at 27, few would argue that this constitutes a sufficiently large proportion of deaths.

Increased risk of death extends beyond age 27 to early adulthood and middle age

The idea of the 27 Club has been imprinted into the collective imagination by books on the subject – such as Howard Sounes’s biographical book 27, on the big six 27-ers, Sarah Milne’s wider coverage of pop musicians who have died at 27, and Michael Owens' more fanciful treatise on the significance of the age of 27, together with continued media fascination with the notion.

But other investigations into the 27 Club, for example, by Eric Segalstad, Martin Wolkewitz, and mine, have concluded that the age of 27 does not bestow any greater risk of death in popular musicians than other ages.

Notwithstanding, all of these studies have identified an increased risk of death in pop musicians during the younger decades of the lifespan compared with the general population.

Sampling strategy and sample size varied between studies but the conclusions were essentially the same, as in my recent research findings, that pop musicians die younger than the general population.

Wolkewitz and his colleagues studied the 1,046 musicians who had a number-one album in the UK between 1956 and 2007 and found that the death rate per 100 musician years for age 27 (0.57 deaths) was similar for other ages: age 25 (0.56 deaths) and 32 (0.54 deaths).

They concluded there was no peak in risk at 27 years, but observed a two- to three-fold increase in risk of death for British pop musicians with number-one albums between 20 to 39 years compared with the general UK population.

The 27 Club is not just about the numbers

I would like to give some comfort to those who might grieve the demise of the 27 Club.

While the actual numbers of pop musician deaths don’t show a spike in deaths at age 27 and hence do not support the 27 Club, there appear to be qualities shared by the 27-ers that stand them apart from many other deceased young pop musicians, which may go some way to understanding how this club entered the pop culture psyche.

These qualities include exceptional talent, the contribution of groundbreaking innovations in their musical genre, intense psychological pain, a squalid death at their peak, and immortalisation – each of “the tragic six” has become a cult figure.

Jimi Hendrix was described in Rolling Stone as:

the greatest guitarist of all time […] one of the biggest cultural figures of the Sixties, a psychedelic voodoo child who spewed clouds of distortion and pot smoke.

His unrepeatable virtuosity on the electric guitar received the following citation in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame:

[Hendrix] expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar into areas no musician has ever ventured before. His boundless drive, technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll.

Janis Joplin, “the greatest white blues mama who ever lived”, was crowned “First Lady” and “Queen” of Rock and Roll. She died only two weeks after Hendrix. Although the official cause of death was heroin overdose, Janis fell into a “yawning chasm of tortured loneliness”. Then, “the life was gone, the legend was born”.

Just a year later, in 1971, the wild, handsome, charismatic Jim Morrison exited the pop music scene in similar fashion. Because of the proximity of these three deaths, the kernel of the idea of a 27 Club was born.

Brian Jones (d. 1969) and Robert Johnson (“King of the Delta Blues Singers”) (d. 1938) became retrospective members; Kurt Cobain (d. 1994) and Amy Winehouse (d. 2011) have reinforced the idea in recent times.

Immortalised in death, a life-size bronze statue of Amy Winehouse has just been unveiled in London.

The Conversation is currently running a series on Death and Dying.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments