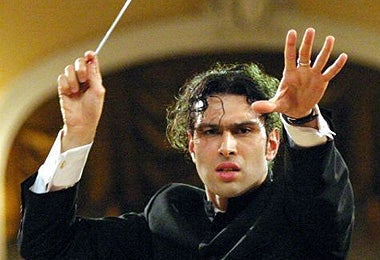

Vladimir Jurowski: Taking up the baton

At 35, Vladimir Jurowski is young to be the LPO's new principal conductor, but musically he's wise beyond his years, discovers Edward Seckerson

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

There's no such thing as a casual conversation with Vladimir Jurowski. The gifted young Russian conductor, who today assumes the role of principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, brings the same intensity to talking about music as he does to performing it. He weighs and considers your words as carefully as he does his own. Don't violate his pauses; he won't violate yours. Pauses are for thought, so think before speaking. He is gracious and charming but doesn't do small talk. An innocent remark will be scrutinised as thoroughly as something more significant.

Shortly after sitting down for this interview, I blithely comment on how much learning he has packed into his relatively short life (he is 35). He counters immediately: "But learning isn't knowledge. Learning is the assimilation of information, and information is dead weight until it has been processed. It's not the same as knowing. It's not knowledge."

He's right, of course, but just now and again, you hope that you might be allowed a careless observation for good behaviour. The fact remains, though, that of all the conductors I have met over the years, Jurowski is probably the most perceptive, well read and tirelessly inquisitive. He is a veritable treasury of information, none of it useless, most of it "processed", to use his word.

Music, of course, is at the very heart of everything for him – it isn't just his profession but his obsession. It all began with his father, Mikhail Jurowski – also a conductor and a very fine one at that. He was Vladimir's first teacher, and it is with evident pride that Jurowski Jr can trace his musical inheritance back to the Austro-German tradition created by Gustav Mahler. (His father studied conducting with Leo Ginzburg, who had been Otto Klemperer's assistant at the Kroll Opera in Berlin in the 1920s. Klemperer in turn had assisted Mahler in the first performance of the Second Symphony, Resurrection.)

"At first, studying with my father was the most natural thing in the world. I was grateful to have him as a guide, to be able to grow in the presence of this wonderful musician. But then I started feeling embarrassed about my privileged position, uncomfortable about all his help and advice – which was silly, but it was my attempt to gain autonomy. I needed to discover things for myself."

A pause while he trawls his memory bank for an illustration: "Like Rimsky-Korsakov said to Balakirev, his teacher and guru, 'I cannot always get it right because you have told me exactly how to do so. I need to get it wrong, because then at least it will be my mistake'."

Jurowski's conversation is peppered with such anecdotes. Like all scholars, he likes to back up his theories with a colourful reference or two. But he's leading us towards an indisputable truth here: that great musicianship cannot be learnt. Rather, it is acquired through instinct, osmosis, practice and experience, trial and error. "Sometimes, it is years before you understand what a teacher meant when he said this or that. Only when you've made all the mistakes can you really know."

And that's something of which he's particularly mindful now that he has started teaching himself. Listening to others is, he says, an essential part of any musical education. For him, CDs (especially of live performances) are an invaluable source of information. To experience the tradition of performance from three-quarters of a century ago, to have recordings of the great names of the day, has to be instructive.

Is he never concerned about the dangers of influence? The answer – "no" – doesn't surprise me because Jurowski knows as well, if not better, than most that you can't clone a Furtwängler, a Kleiber or a Bernstein performance. All you succeed in cloning are the mannerisms.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

And that's all they are – mannerisms. The soul of those performances comes from something deeply organic that can only be found within oneself. "I don't have a problem separating someone else's analysis of a piece from my own. I can listen objectively and say – OK, so it can sound like that. Or, so that's how it sounded 50 years ago. But finding my own way to this music, going deep down into it, that is hard spiritual work."

Meditation is one way that Jurowski has found of assisting the process. Daily yoga is another. But suddenly, he says, you are in front of an orchestra, and that's another matter altogether.

The first time Jurowski ever stood in front of a professional orchestra was in 1991, during a master class with Sir Colin Davis. Today, he describes himself as "35 going on 65", and adds to that impression with some peculiarly quaint turns of phrase. Actually, he speaks English better than most Englishmen, but when he uses phrases like, "I am not being coquettish when I say this...", he cuts an endearingly old-fashioned figure. He also reminds us that true intellect is not some gift of class or circumstance, but the fruit of learning.

Which brings us to the whole issue of intellect versus spontaneity in music-making – because I am aware (and I think he is, too) of an ongoing conflict between the two. Sometimes in Jurowski's performances there is a sense of the one inhibiting the other – meaning that, occasionally, his analytical approach to a score will come between us and its emotional core. He acknowledges that it's a delicate balance, adding that "expressive" is different from "emotional".

"Expressivity is the active force that unlocks the emotion," says Jurowski. "And how you achieve that with an orchestra is at the heart of what music-making is about. I believe it is of the least importance to communicate my emotions about a piece to musicians. It doesn't matter what I feel about the music, or indeed what they feel about it. I agree with Stravinsky that music can but express itself."

But it can and should produce a raft of emotions in the listener? "Of course, but it's not my job to tell an audience what to feel." Haven't great conductors such as Leonard Bernstein done that? Wasn't he pilloried for "acting out" pieces on the podium?

"Bernstein was a performing composer. I am not. He came to conducting through composition – like Mahler – and that gave him a totally different perspective when it came to interpreting other composers' work."

Yes, it did. But in spite of such fundamental differences in approach (and in personality), Jurowski still acknowledges Bernstein as a major inspiration. Like Bernstein, the theatre has coloured a lot of what Jurowski has sought to do in the concert hall. The one inevitably impacts upon the other. Conducting his orchestra – the London Philharmonic – at both Glyndebourne and the Festival Hall lends a whole new meaning to the phrase "the best of both worlds".

For the LPO, the Jurowski era begins with a programme that starts as he means to go on: Wagner's Parsifal Prelude; Berg's Three Orchestral Pieces; and the original version of Mahler's astonishing Das klagende Lied. That's not a programme, that's a manifesto. Indeed, such is the inventiveness and originality of Jurowski's programming in his first season that, for the first time in perhaps a decade, we can predict the unpredictable on the South Bank.

The LPO's 2007/8 season under Vladimir Jurowski begins tonight at the Royal Festival Hall, London SE1 (020-7840 4242)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments