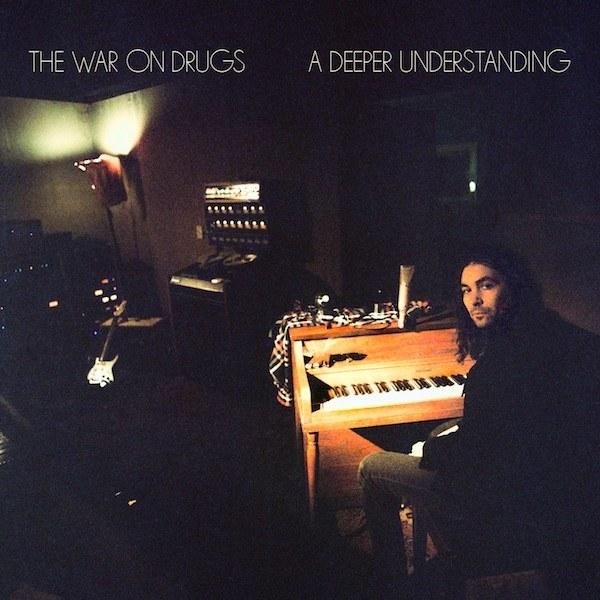

The War on Drugs' Adam Granduciel on new album, creative control and roots in Philadelphia

The Philadelphia sextet, who have just released their new album ‘A Deeper Understanding’, are still playing rock the old-fashioned way

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Though the designation would probably make him uncomfortable, Adam Granduciel is – on paper, at least – what passes these days for a rock star.

As the lead singer and songwriter for The War on Drugs, one of the least likely breakout acts of this decade, Granduciel has taken an old-fashioned concept – the rangy, six-string-centric American band, steeped in reverence and grandiosity – and made it newly relevant, with more guitar solos than narrative or musical gimmicks.

On the strength of The War on Drugs’ sweeping 2014 album, Lost in the Dream, Granduciel, an unassuming frontman with a tangle of shoulder-length curls, went from toiling on the local indie circuit to headlining international music festivals and even signing a major-label record deal, a rarity for a 38-year-old traditionalist heading into his fourth LP.

“Maybe there was a void for a split second and then we were there,” Granduciel says, declining to muse much on the state of modern rock’n’roll, which has all but disappeared from the Billboard charts. “I don’t think about it too much,” he insists.

But while Granduciel may be a reluctant saviour of rock culture, commercialism and bombast – personally, he has remained largely anonymous, even while, in another throwback move, dating a famous actress, Krysten Ritter (Breaking Bad, Jessica Jones) – he is a careful steward of the sound, an obsessive studio rat in constant search of the authenticity he sees in titans like Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and Neil Young.

“Adam knows his record collection,” says Steve Ralbovsky, a veteran music executive who courted The War on Drugs for Atlantic Records, which released the band’s new album, A Deeper Understanding, today (25 August). “The people that he’s plugged into, he’s plugged into deeply.”

As another exercise in that devotion, A Deeper Understanding is free of any compromises that might be expected to come with new corporate backing. The initial offering from the album, an 11-minute, multi-movement epic called “Thinking of a Place”, was representative in its ambition and sure-footedness: most of the record’s ten tracks clock in at over six minutes.

Loose but not noodly, the reverb-heavy songs luxuriate in space yet find a centre in Granduciel’s plaintive, placeless drawl and facility with layering rich textures that manage not to clutter. (On one track, Granduciel, who wrote, produced and recorded the album, is credited with playing ten instruments on top of singing.)

Such a vintage, singular vision may not sound like a Spotify blockbuster, but neither is it as niche as remaining rock purists might fear. Powered by relentless touring and critical adoration, Lost in the Dream – the most acclaimed album on year-end lists in 2014, as tallied by Metacritic – has sold more than 255,000 copies (including streaming equivalents), according to Nielsen; some 114,000 of those sales were physical, defying overall trends but in line with a vinyl boom among certain indie-rock types.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Bruce Warren, the programme director for Philadelphia’s alternative FM public radio station WXPN (tagline: “Vinyl at Heart”), recalled the word-of-mouth growth the band experienced across age groups. “The millennials and the boomers were all coming together over classic rock,” he said. “These guys are playing tomorrow’s classic rock today.” (Jimmy Iovine, the Apple executive and former label boss who also worked as an engineer on Mr Springsteen’s Born to Run, has said that The War on Drugs “should be gigantic”.)

Granduciel, a careful talker who often self-censors rather than finish a sentence, does not shy from such lofty associations, freely referring to “Bruce” when nerding out over studio lore. Still, he retains a believable working-class humility and dedication to craft and leadership, even – or especially – as his band’s impact and resources have increased.

“I think of it as a small business,” he says in the gear-strewn rehearsal space where the band recently settled in South Philadelphia. “I have employees, overheads.” While the group’s lineup has varied since it started in 2005 as a partnership between Granduciel and the singer-songwriter Kurt Vile, who left after the band’s 2008 debut, Wagonwheel Blues, The War on Drugs currently includes the musicians Dave Hartley, Robbie Bennett, Charlie Hall, Jon Natchez and Anthony LaMarca.

Though Granduciel fears a reputation for micromanaging, especially given his creative dominance – Hartley plainly calls the band “a totalitarian regime” – he involves himself in all War on Drugs matters, from label business to hiring road crew to travel accommodations for band members during recording.

“Ten years ago, I believed if you thought about that other stuff it meant you weren’t a serious artist,” Granduciel says. “I’ve just grown up. Respecting yourself and your art means taking an interest in the other responsibilities.”

At the same time, he enjoys being held accountable. “I like to work hard and I like to work for somebody,” says Granduciel, who was raised in suburban Massachusetts and had jobs in a bookstore and at a Friendly’s restaurant. “I like to stay late and clean up the back and show the boss in the morning.”

In Atlantic, and especially Ralbovsky, he found such an authority. After three albums on the independent label Secretly Canadian, The War on Drugs became free agents just as their stock was highest, near the end of 2014. “I didn’t want to start aiming for fame,” Granduciel says, but “it would be silly to not have entertained offers.”

His non-negotiable demand? Complete freedom.

“It’s like an indie-rock deal with a major,” Granduciel says. “All the things were lining up to this one moment, so I’m just going to f***ing do it,” he recalled thinking. “It’s two records for Atlantic, full creative control. What more do you want?”

He was also drawn to the pedigree of Ralbovsky, who had worked with Tom Verlaine (of Television) and The B-52s in addition to signing crossover rock acts like the Strokes, Kings of Leon and My Morning Jacket.

“For the most part, I’ve signed bands at the very beginning of their career,” Ralbovsky says. But even without youthful sex appeal or a hit single, he was intrigued by The War on Drugs, “a great band at the peak of their powers” that had “just made a landmark record”.

Following that up was another matter, especially for Granduciel, whom Ralbovsky called “a real perfectionist, a real sculptor”. He added, “Anybody that tells you they didn’t feel pressure after signing a new deal with a big company, they’re not telling you the truth.”

For The War on Drugs, those expectations were compounded by memories of making Lost in the Dream. Saddled with anxiety and prone to panic attacks on top of his obsessive attention to sonic detail, Granduciel nearly destroyed himself on the way to his musical breakthrough.

“There’s an alternate universe in which that record never gets finished,” says Hartley, the band’s bassist, who met Granduciel more than a decade ago, when the singer was “fairly broke and sort of a mess,” but in an “inspiring way.”

However, during the “pretty tortured” recording process for Lost in the Dream, Hartley recalled Granduciel as a self-lacerating defeatist: “There was not a single time we’d listen and be stoked. It was always him being upset.”

Hartley adds that Granduciel “has to self-immolate a little bit to feel like he’s created something true to himself. I’m not going to lie to you, it’s a little bit tough to be involved with as a bandmate.”

Granduciel credits touring, cognitive behaviour therapy and a change of lifestyle with his ability to make another album and keep the group together.

“I think he came out of it a better person,” Hartley says. “He used to be a partyer, a heavy drinker and pretty freewheeling socially. He completely became an ascetic – no coffee, no booze, no drugs, limited types of food. He’s just a bit more well-adjusted.”

The content of A Deeper Understanding — with songs titled “Up All Night,” “Pain,” “Holding On,” “Knocked Down,” “In Chains” and “Clean Living” – indicates a continued reckoning; Granduciel calls it the tying-up of “a lot of loose ends”.

But he found purpose and structure in more than a year of writing and recording those songs, and he committed himself to involving his bandmates more in this album’s creation for a sound closer to the group’s live show. (The recording engineer Shawn Everett, known for his work with Alabama Shakes, said he aimed to “to keep the psychedelic fog” of Lost in the Dream “but maybe press the gas on the ambition a little bit” for A Deeper Understanding.)

Granduciel, who spent time between tours in New York and Los Angeles with Ritter, also vowed to make Philadelphia, where The War on Drugs formed, its home base. “Having a moderately successful indie-rock record and living in LA full-time,” he said, “was the antithesis of what I wanted to be.”

He pointed to a band like Wilco, the experimental indie stalwarts from Chicago, as a model for The War on Drugs’ future: “self-sustaining, self-governing, great fan base, tight connection to their roots – that’s what we’re trying to build over here,” Granduciel says.

“I just need to work,” he adds. “There’s no other thing with me.”

The War on Drugs’ ‘A Deeper Understanding’ is out now

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments