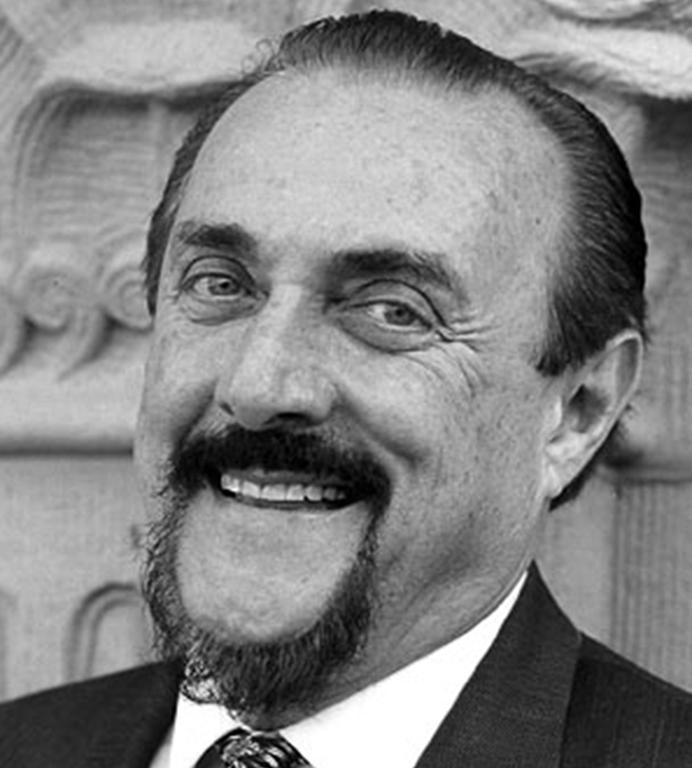

The Stanford Prison Experiment: ‘put people in bad barrels and they’ll become bad apples’

A new movie charts how Philip Zimbardo’s famous 1971 project at Stanford University in California had a devastating effect on those involved

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Human Subjects Research Committee at Stanford University in California had only one concern about Dr Philip Zimbardo’s now infamous prison experiment: was it a fire hazard?

“College kids playing cops and robbers in a simulated prison in a university – what could go wrong? That’s what the committee said,” says Zimbardo. “They came down and looked at the prison. There were no windows and only one entrance. They said if there was a fire it could be dangerous, and insisted that I get carbon-dioxide fire extinguishers. The ‘guards’ ended up using them on the ‘prisoners’.”

For just under a week during the summer of 1971, Zimbardo was chief superintendent of his very own “prison” in the basement of Stanford’s psychology department. Offices were converted into cells, the corridor was turned into a yard and a janitor’s cupboard became the “hole”. Twenty-four students – mostly white, middle-class and mentally sound – had been selected to play the roles of prisoner and guard. Like the committee said: what could possibly go wrong?

A new drama film, The Stanford Prison Experiment, shows in claustrophobic detail how very wrong things went. Several of the nice, sane, well-educated kids who had been chosen at random to be guards soon began to derive pleasure from psychologically torturing the prisoners. Others simply stood by and did nothing while their colleagues sexually humiliated inmates, deprived them of sleep, forced them to defecate into buckets, and much more besides. The experiment, which was meant to last two weeks, had to be cut short after six days.

The seemingly obvious conclusion: put people in bad barrels and soon enough they’ll become bad apples. Evil actions are caused by evil situations, and individuals to have little say.

After almost half a century, Zimbardo’s work continues to capture people’s imaginations. The idea that evil lurks within all of us and, like a seed beneath the soil, and needs only the right conditions to flourish is a compelling one. But has his work stood the test of time? And what can it teach us today?

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the ethics of clinical psychology were about as developed as law enforcement in the Wild West. But for Zimbardo, “it was a wonderful era … in which they were just beginning to have concerns about the limits to what you can do in an experiment”.

And it was an era that allowed the prequel, of sorts, to Zimbardo’s prison study: Stanley Milgram’s famous work on obedience to authority. “He and I were high school classmates doing the same exact class when we were 17-year-old high school seniors,” says Zimbardo. “He was a little Jewish kid, smart. He was obsessed with this question: could the Holocaust happen again in America? Could his family end up in concentration camps?”

Milgram’s experiment, in which subjects obediently administered what they thought were deadly electric shocks to an unseen actor, caused them a level of mental anguish (when they eventually realised what they’d done) that would not be permitted today. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine the prison experiment, which scored its first of several nervous breakdowns within 36 hours, being cleared by a modern ethics committee.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“No such research can ever be done again,” says Zimbardo. “The human subjects committees have gone to the far extreme. You cannot do anything in research that causes undue stress to participants. It eliminates so many key questions on human nature.”

While the stress caused to the prisoners was, in many cases, unbearable, the transformation undergone by those inflicting it – the guards, the head of the parole board and even Zimbardo himself as prison superintendent – was truly remarkable.

“One hundred per cent of the participants, when asked, said they wanted to be a prisoner,” says Zimbardo. “In 1971 they hated guards and hated police. Students were rebelling against the Vietnam War. Most universities called the police on campus and they beat up students. Guards were pigs. Nobody wanted to be a guard, but in one day they became a guard. For me that’s still fascinating.”

Such, says Zimbardo, was the power of the situation. It’s a claim that seems hard to refute. Even a hardened ex-convict, Carlo Prescott, who had recently emerged from 17 years hard time in San Quentin, became “everything he hated” when Zimbardo signed him up as head of the parole board.

“In the study he said: I hate parole board officers, they humiliated me,” says Zimbardo. “[But] in that moment he became the composite of all those terrible parole board officers that turned him down. In some cases prisoners were literally crying. At the end, Carlo said: ‘I’m sick. I don’t know what happened in there. I became my enemy.’”

Whether or not the Stanford Prison Experiment was ethically or even practically sound – there is some evidence to suggest that those willing to sign up to such things have greater authoritarian tendencies than most – it left Zimbardo with a deeply held conviction that systems and situations should be held to account when individuals turn bad.

Following this belief led Zimbardo from Stanford to Hollywood, via Baghdad. It was a long journey. Zimbardo published a few articles after the prison experiment, and then moved on to different things: initially studying “shyness as a self-imposed psychological prism”. It wasn’t until the abuses carried out by American military personnel in Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq came to light in late 2003 and early 2004 that he felt the need to return to his earlier work in depth.

“Former students started writing to me, saying the images were exactly from my study,” says Zimbardo. “They were putting bags over their heads; they were naked. So I made a statement: our soldiers are good apples, and somebody put them in a bad barrel. We have to know who are the bad barrel-makers, because that’s the evil in the system.”

Zimbardo ended up acting as an expert witness for the defence of Chip Frederick, one of the first soldiers to face trial for torture at the prison.

“The military created a situation and then absolved themselves of any responsibility,” says Zimbardo. “It’s not the grunts who should be punished. It’s the entire chain of command which has to be called to question.”

From that experience emerged a book – The Lucifer Effect – which looked back at the prison experiment in detail, and from that arose the film script, which is, says Zimbardo, “90 per cent accurate”.

The Stanford Prison Experiment, directed by Kyle Alvarez, makes for hard viewing, partly because many of the scenes seem so reminiscent of the Abu Ghraib abuses. In this case, however, it was Zimbardo who was the bad barrel-maker. During his six days as prison superintendent, he becomes indifferent to human suffering; at other times, he seems to encourage it.

“We cannot physically abuse or torture them,“ says Zimbardo to his guards at the start of the film, echoing words spoken in 1971. ”We can create boredom. We can create a sense of frustration. We can create fear in them, to some degree. We can create a notion of the arbitrariness that governs their lives, which are totally controlled by us, by the system, by you, me … In general, what all this should create in them is a sense of powerlessness. We have total power in the situation. They have none.”

As well as following a somewhat maniacal Zimbardo (“I think in the back of their minds, the writer and director had this mad scientist image,” he says), the film examines the progress of two participants: the heroic, rebellious prisoner 8612 (played by Ezra Miller) and one of the most sadistic guards, nicknamed John Wayne.

The perverse realisation, delivered halfway through the film, is that the only thing differentiating the hero from the villain is the toss of a coin. The jackboot could just as easily be on the other foot. Can we really have so little agency?

“We like to believe that we are masters of our fate,” says Zimbardo. “The key is that we are when we are in familiar situations. My experiment and the Milgram experiment put people in totally new situations where they didn’t have any bearing. They’re trying to figure out what do they do that’s appropriate. In this case, you know people are looking at you, so you want to do the right thing in that situation. If you’re a guard, the right thing is the kick prisoners’ asses.”

“I hope the film is an experience,” says director Kyle Alvarez. “I wanted to create a movie that leaves you a little breathless at the end and you feel you watched something harrowing but then you have a conversation. The number one primary goal is to leave you talking.”

No doubt it will. The continued power of the Stanford Prison Experiment lies in its ability to force people to consider what sort of guard they would be, or what sort of prisoner. Would you rebel? Would you oppress? Or would you passively allow the oppression of others? Perhaps you already do.

“We are all prisoners and guards in various ways in our lives,” says Zimbardo. “If we’re prisoners, we hope to do things that give us appropriate amounts of power; if we’re guards, to be sensitive to the misuse of our power. That’s really the message: to be aware of whatever power you have and to try to figure out how you can use this power to make the world better.”

‘The Stanford Prison Experiment’ is in cinemas from Friday, on digital download from 13 June and on Blu-ray and DVD on 27 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments