The dark side of the boys and girls from Brazil

It may have become the epitome of laid-back cool, but, as a new book relates, the bossa nova was forged in turbulence. By Ian Burrell

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Helo Pinheiro, "tall and tan and young and lovely", made her way through an artsy neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro on her daily walk to the beach, she was the unwitting muse for a song that has become symbolic of an entire musical genre, bossa nova.

Passing the Veloso café bar, sometimes popping in to buy cigarettes, Pinheiro inevitably caught the eye of café regulars Antonio Carlos "Tom" Jobim, a composer, and Vinicius de Moraes, a lyricist. She inspired them to write "Garota de Ipanema" ("The Girl from Ipanema"), which became the internationally recognised sound of modern Brazil, winning the Record of the Year at the 1965 Grammys.

Except that the vision it inspired was a fallacy. In the real Rio de Janeiro in 1964, the army was on the streets, staging a military coup. "Everyone has this stereotypical image of bossa nova as jet-setting cocktail music and yet there were tanks rolling down the streets," says Stuart Baker, co-author of a new book, Bossa Nova and the Rise of Brazilian Music in the 1960s.

"The Girl from Ipanema", he points out, has obscured the fact that bossa nova was a radical sound, the first musical representation of the state of Brazil and the root of Brazilian music today. It was the soundtrack of a wider creative movement that was born in the late 1950s and included the film director Glauber Rocha and the architect Oscar Niemeyer, best known for the public buildings of the country's capital, Brasilia.

With the modern Brazil ranked with Russia, India and China as one of the great "Bric" emerging economies, and the prospect of hosting the World Cup in 2014 and then the Olympics in 2016, it is easy to forget that the country has been through a previous economic revolution. At the end of the 1950s, Brazil was moving from the Third World to the First World at warp speed or, in the words of the president of the time, Juscelino Kubitschek, making "50 years of progress in five". In 1958, Brazil won the World Cup for the first time, thanks to a 17-year-old Pele.

"Bossa nova reflected this period of optimism in the country," Baker says. "Beautiful melodies, angular and complex jazz harmonies, sophisticated word play and a poetic lyricism defined bossa nova as distinctly modern, cool and cosmopolitan."

Although Brazilians had long been dancing to samba, the musical genre that to this day is most commonly associated with the country has long Afro-Brazilian roots that pre-date the modern state with its new washing machines, automobiles and motorways. Bossa nova was the sound that accompanied Brazil's transition from a predominantly rural-based society to an industrial one.

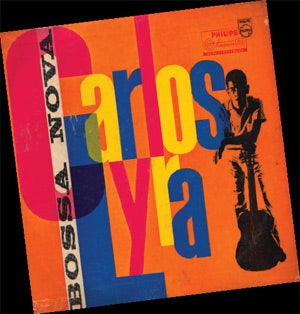

And part of this "first Brazilian cultural wave", as Baker puts it, was the arresting artwork that adorns the record sleeves of bossa nova and which provides much of the imagery for his coffee table book. Bossa nova sleeves are invariably red, black and white. They are as distinctive as the covers of New York's Blue Note, with which the movement briefly competed for the attention of jazz followers around the world. "You could spot the covers a mile off," Baker says.

The man who did most to define the look of bossa nova was Cesar Villela. Inspired by the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, Villela was a minimalist. "He was going to Brazilian record shops and all the sleeves were all full-colour – everything in the photographs was sunny, as you can imagine. He said, 'I need to make something much more striking'," Baker says. "Every other bossa nova record company copied this style, quite clearly, so across the whole of bossa nova there are so many covers that are black, white and red. It becomes the whole of the music."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Villela designed the cover for the first hit bossa nova album, 1959's Chega de Saudade ("No More Blues") by Joao Gilberto, a guitarist from the north-east of the country. The album's title track was another composition by Jobim and De Moraes.

It was the work of Gilberto – the undisputed star performer of bossa nova – and Jobim in particular that attracted the interest of American jazz musicians, and in 1962, the West Coast saxophonist Stan Getz and the guitarist Charlie Byrd released a hit album of Brazilian songs, Jazz Samba. Byrd had heard the music of Gilberto during a visit to Brazil in 1961 and taken bossa nova records back to the United States. In November 1962, Gilberto, Jobim and a group of other musicians in the vanguard of bossa nova were invited to perform at Carnegie Hall in New York. The show was so successful that Gilberto and Jobim stayed in America and made it their base.

But as bossa nova began to find an American audience, inflation and the national debt were raging out of control back home. Relations with the United States were deteriorating, especially after the ascent to the presidency of the left-winger Joao Goulart. In line with the growing political tensions, the themes of bossa nova began to change from the sunny love songs of the years before to more radical lyrics and socially conscious artists such as Edu Lobo.

It was against this backdrop that Getz, Gilberto and the Brazilian's wife, Astrud, recorded "Garota de Ipanema". When it was released in 1964, it caught the world's imagination of a Brazil of carefree seaside romance and was a global hit just as, on 1 April, the tanks arrived in Rio to enforce a military coup that lasted for the next 21 years. In a certain irony, it transpired that Pinheiro, the girl who had inspired the hit song on her walks down to the beach, was herself the daughter of an army officer. After a lifespan of just six years, bossa nova disappeared overnight. But you can hear its influence today as a heartbeat of the diverse sounds of a Brazil which is once again seized by a sense of optimism.

'Bossa Nova and the Rise of Brazilian Music in the 1960s' by Gilles Peterson and Stuart Baker is published by Soul Jazz, £25. An accompanying CD will be released in January.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments