How Pornography brought The Cure to the brink

Ahead of their headline set on the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury, Ed Power looks back on how drugs, drink and the recording process turned goth-rock troupe into ‘a powder keg ready to explode’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Summer 1982 was drawing to a fitful close when Robert Smith slid his guitar under the bed, scrubbed away the last of the mascara and packed his sleeping bag. The Cure frontman was about to step outside the door of his parent’s house in Crawley, West Sussex, and away from the goth-rock troupe he had led to unlikely success across the previous six years. He was heading into the blue yonder in a desperate attempt to silence the tumult in this head, the chaos that had come crashing down on his music career.

He didn’t tell anyone but he suspected that, after four albums and a lifetime of upheaval stuffed into half a decade, it might be the end for the band. As far as Smith was concerned, The Cure were over. And so here he was, a literally unhappy camper about to hit the road. “Everything seemed to be going wrong,” Smith would recall. “So I decided to go off for a few months. I took a tent and went around England.”

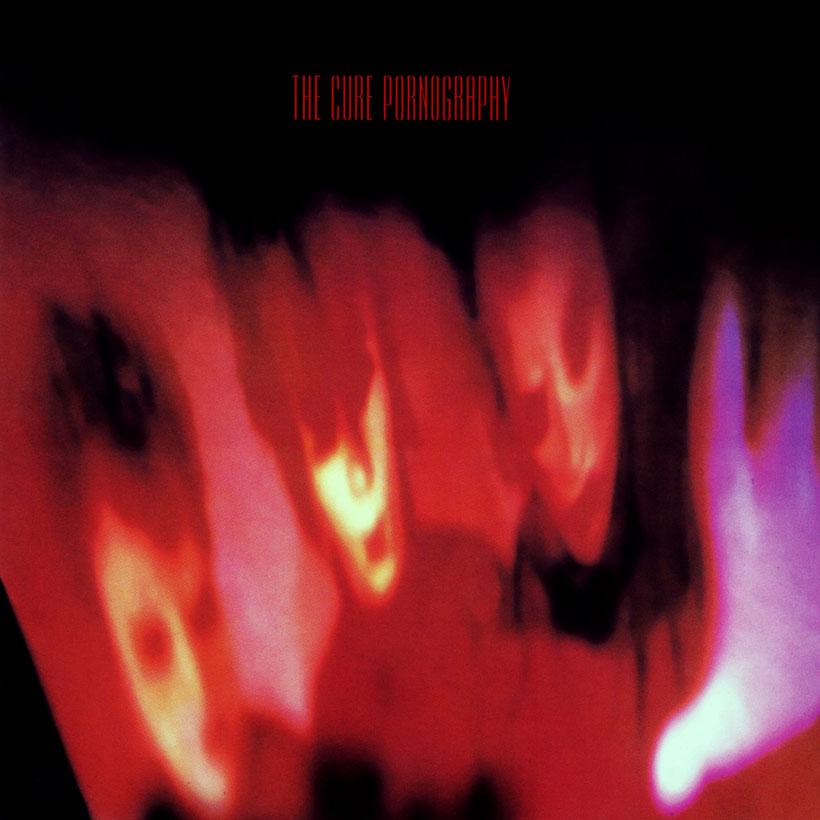

The Cure would rise like a moody phoenix, of course, and this Sunday they tick another accomplishment off their bucket list when they headline the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury. They come to Pilton after an extensive European tour that has seen them revisit every phase of their career with one notable exception. Conspicuously glossed over is the period leading up to Smith’s 1982 meltdown and his desperate camping excursion. Just one song on the 2019 setlist, the toweringly foreboding “One Hundred Years”, is from Pornography. The torrid fourth album that drove Smith over the brink and nearly devoured the band is otherwise out of sight and out of mind.

“Everything got to be too much. The whole thing had become too intense” is how Smith summarised that period in The Cure’s history. “It was very depressing. Everything seemed to be wrong. We didn’t achieve what I wanted us to achieve. Me and Simon were just fighting all the time.”

Simon Gallup was The Cure’s bass player in the definitive early line up (Gallup had first crossed paths with Smith while playing in another band, Lockjaw, at the Rocket pub in Crawley in February 1978). Always volatile, the relationship between frontman and bassist had taken a turn for the worse recording Pornography.

Drugs and alcohol were becoming a dangerous crutch for the musicians. To further darken the mood, someone had suggested that they explore disturbing imagery (they have never gone into the details). It added up to six months of unexpurgated hell. “During Pornography, the band was falling apart, because of the drinking and drugs. I was pretty seriously strung out a lot of the time,” Smith confessed to Rolling Stone. “I know for a fact that we recorded some of the songs in the toilets to get a really horrible feeling, because the toilets were dirty and grim. Simon doesn’t remember any of that, but I have a photo of me sitting on a toilet, in my clothes, trying to patch up of some of the lyrics. It’s a tragic photo.”

“We immersed ourselves in the more sordid side of life, and it did have a very detrimental effect on everyone in the group,” he continued. “We got ahold of some very disturbing films and imagery to kind of put us in the mood. Afterwards, I thought, ‘Was it really worth it?’ We were only in our really early twenties, and it shocked us more than I realised – how base people could be, how evil people could be.“

As is often the case with well-brought-up young Englishman who find themselves living in proximity for months on end, The Cure had never really had a proper row up until that point. So instead of being aired in a healthy fashion, tensions simmered. It all came to a head in spring 1982 as Smith, Gallup and drummer Lol Tolhurst, a school pal of the singer’s, set off on a European jaunt to promote Pornography.

They were proud of the album, but also tremendously uneasy about it. Smith, intense even by the standards of a 23-year-old songwriter, had conceived of Pornography as cathartic final statement, following on from its almost (but not quite) as bleak predecessors.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

”Seventeen Seconds“ and ”Faith“ had been an outlet for the shy and sensitive Smith’s deepening alienation. These negative feelings had threatened to overwhelm him as The Cure evolved from club-circuit underdogs to international rock stars. It didn’t help that he had a parallel career playing guitar in Siouxsie and the Banshees. When he wasn’t leading The Cure, he was touring with the Banshees. The pressure was asphyxiating.

Pornography took his angst to another level. It was flensing torture-porn pop, steeped in haggard guitars and Smith’s edge-of-sanity caterwaul. All the LSD and boozing didn’t help. “We had an arrangement with the off-licence up the road: every night they would bring in supplies,” Smith subsequently revealed to Mojo. “We decided we weren’t going to throw anything out. We built this mountain of empties in the corner, a gigantic pile of debris in the corner. It just grew and grew. At the time, I lost every friend I had, everyone, without exception,” he added. “I was incredibly obnoxious, appalling, self-centred.”

The misery, the confusion, the pounding hangovers… all of it seeped into the songs. “My heart explodes/My memory in a fire,” Smith sings on “The Figurehead”. “One more day like today and I’ll kill you,” he adds on the title track. “I must fight this sickness.”

Pornography was released on 4 May, peaking at number eight in the album charts. The critical response, though, was muted and confused. “Pornography comes off as the aural equivalent of a bad toothache. It isn’t the pain that irks, it’s the persistent dullness,” shrugged Rolling Stone. “Robert Smith seems locked in himself, a spiralling nightmare,” added Sounds. Melody Maker reckoned it was “downhill all the way”. The Quietus has since diagnosed it as “a vision of hell”.

Rather than retreat from the dark forces the album had uncorked, The Cure seemed determined to drag their audience down with them on the accompanying tour, as Tolhurst outlined in his autobiography Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys.

“[The stage] was confrontational compared to what had come before,” he wrote. “[It] comprised of screens that were remotely operated to come down over the drum kit which was placed to the side of the stage. They also covered other areas of the stage to create different effects. It was stark to say the least ... The effect was similar to sitting in a pub or club with a mirror bar ... A little disconcerting for the audience, which was part of our intention.”

It was clearly too disconcerting, as The Cure fanbase stayed away in numbers. At Dusseldorf Philipshalle on 20 May, The Cure played to a two-thirds empty room. In Strasbourg a week later, the tension between Smith and Gallup finally reached snapping point. Another moody, brooding gig had left the band stewing. Afterwards, as Tolhurst relaxed with County Wexford support act Zerra One, a disagreement occurred between Smith and Gallup over an unpaid bar tab. On that night, The Cure as it had existed would sputter and die, never really to return.

“When you’re firing on all cylinders it’s OK to keep going, especially when you’re young and enthusiastic,” wrote Tolhurst.” But we really hadn’t had much of a break in the three years since we’d signed with Fiction [the band’s label]. No wonder we were in such a frazzled state. Add heavy drinking and drug use and we were a power keg really to explode.”

Explode they did. The argument between Smith and Gallup erupted into a fully fledged fist fight. Smith stormed out. Then Gallup vanished too. Still in Strasbourg, Tolhurst found himself without a singer or a bass player – and with the Swiss, French and Belgian legs of the tour to be fulfilled.

Smith had gone home to Crawley, having taken The Cure as far as he thought he could. Gallup was done with the band too – and with Smith. The only one in the camp who felt The Cure should continue, in the short-term at least, was Smith’s father. When the singer arrived on the family doorstep, Mr Smith didn’t hold back in his opinions. “In a bar in Strasbourg things got so out of hand that I just took the first flight home,” Smith junior remembered. “For me it was over and out. But when I unexpectedly showed up home, my dad wouldn’t let me in. ‘You have a responsibility as an entertainer,’ he said. ‘People have bought tickets, get yourself back on tour’.”

So he and Gallup went back and finished what they had begun. Yet far from mending fences, they seemed even more determined to burn the entire edifice to the ground. Shortly before going on at the final show in Brussels on 11 June, Smith decided he wanted to play drums. In a fury, Gallup snatched Smith’s guitar and stomped on stage. Tolhurst, having little choice, took over on bass.

The gig was a surly, clattering affair. A roadie who was friendly with Gallup walked on and shouted “Robert Smith is a c***” into the mic, while Smith threw his drumsticks at Gallup, yelling “f*** off”. “That night… felt like death,” Tolhurst would write. “It was the death of that version of The Cure.”

”I remember that we were in the dressing room and I thought in one hour The Cure is finished,” Smith would add. “So I thought: let’s make it a memorable goodbye.”

And that truly seemed to be that. The tour ended, Smith packed his tent and off he went. “It was a very traumatic time for us. We’d reached the end of the road really. We couldn’t really go any further…we’d just reached a complete dead end. It was more like the edge of a cliff.”

Tolhurst thought it was over too. He was left to his own devices as his former bandmates vanished off the map. But then, a few months later, he received a phone call. It was Smith, back from his tent time and with a renewed sense of purpose. Did Tolhurst want to make a record? It would be just the two of them and everything would be different.

Smith had reached a crossroads. Much like New Order, who had retreated from the void of Joy Division with the suicide of Ian Curtis, he was ready for a new phase. The Cure would continue under their old name. In every other way it would be different (though not so different as to prevent Gallup rejoining in 1984).

What came next was the playful, irreverent Cure of “The Lovecats” and “Close to Me”. Even their heavier songs would have a pop element – as will be clear when they belt out “Lullaby” and “Just Like Heaven” at Glastonbury. As he basks in the acclaim and takes in the moment, though, a little part of Smith may reflect that without Pornography and the trauma that ensued, The Cure would never have become the beloved hit they blossomed into through the Eighties. To step into the light, they had to first pass through the darkness.

“I don’t have particularly fond memories of Pornography, but I think it’s one of the best things we’ve ever done, and it would have never got made if we hadn’t taken things to excess,” he reflected. “People have often said, ‘Nothing you’ve done has had the same kind of intensity or passion.’ But I don’t think you can make too many albums like that, because you wouldn’t be alive.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments