The Cranberries on losing Dolores O’Riordan: ‘She was in a good place – it made it harder to get that call’

As they release their final album, The Cranberries talk to Elisa Bray about their late frontwoman’s unique voice, her battles with anorexia and bipolar disorder, and the band’s enduring legacy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

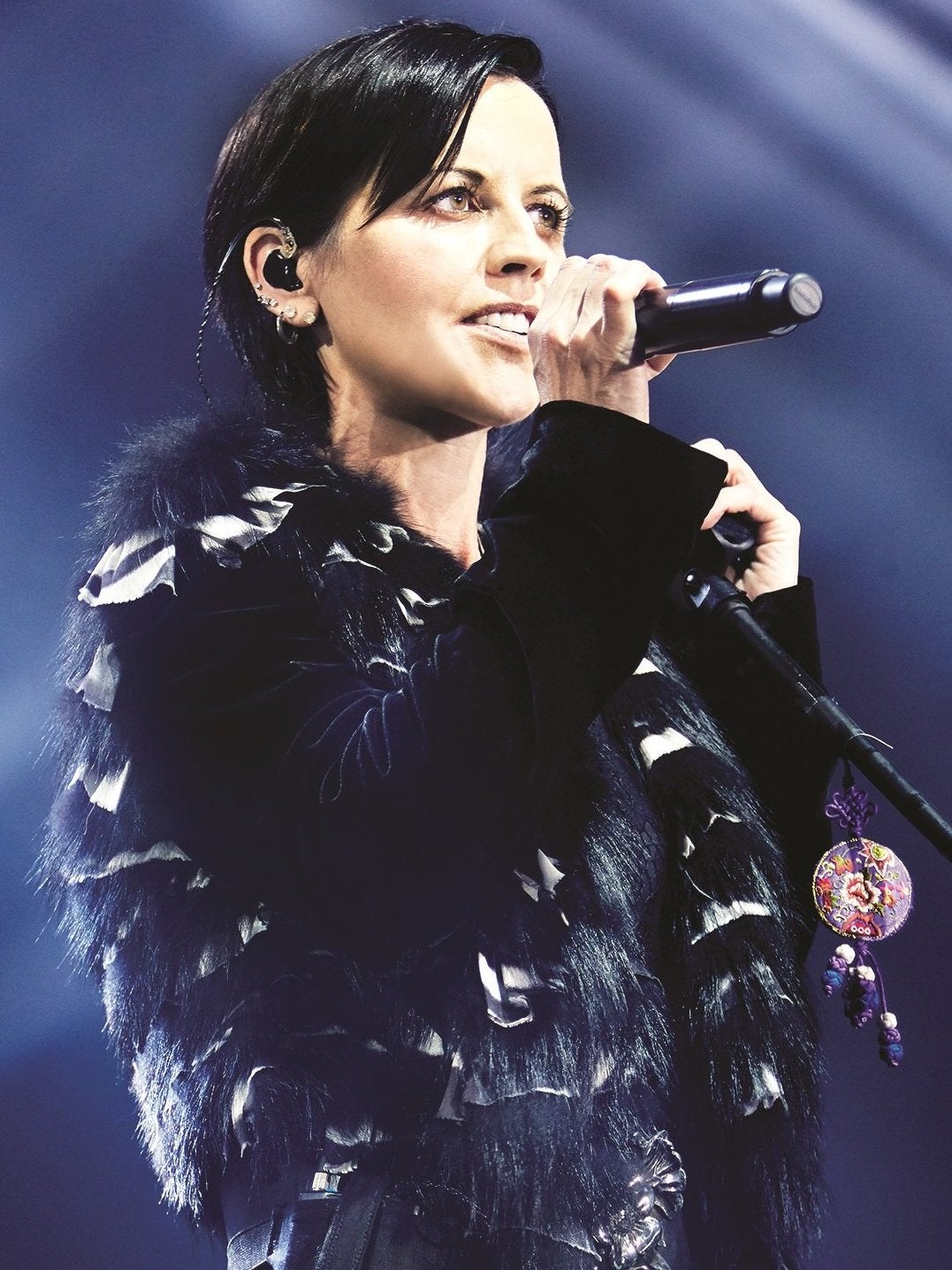

Your support makes all the difference.Fifteen months ago the music world lost one of its most distinctive singers. Dolores O’Riordan, lead singer of Irish band The Cranberries, was the voice of some of the Nineties’ biggest alt-rock hits – from the dreamy yearning of “Linger” to the grungy roar of “Zombie”. But it took her death aged 46, drowning in the bath of a London hotel room after a night of heavy drinking, for her three surviving band members to realise just how much The Cranberries meant to millions around the world. “We had no idea,” says guitarist and O’Riordan’s co-songwriter Noel Hogan. “And then we saw this outpouring of how much of an impact we’ve had. It’s a great legacy to leave behind.”

We’re in the band’s record label offices in London discussing their latest – and final – album, In the End, which gives fans one more chance to hear O’Riordan singing new material. The remaining members – Noel, his younger brother, bassist Mike, and drummer Fergal Lawler – got back in the studio with long-term producer Stephen Street just a couple of months after O’Riordan died. The first few days without her were the hardest. “You’re dragging it all back up again like it happened yesterday,” recalls Noel. “The first day it’s all you could really think about: that she’s not here and what happened to her. You’d put on the headphones and there’s Dolores singing at you again. But the realisation came to us that if we’re going to be moping around like that, we’re not going to be doing these songs any justice.” Hard as it was, focusing on the album helped with the grieving process, adds Mike. “It did take our minds off it a bit. Once we’d got past the first week, and put the emotions aside, it was almost like a therapy.”

With the spotlight now on them rather than their frontwoman, today’s mood vacillates between warm reflection on their almost 30-year career and sad acceptance of their bandmate’s absence. “Dolores would always be here, and you miss that energy she had,” says Lawler, quietly. “That is strange.” In a way, you wonder if O’Riordan would be the one to keep the mood lighter today. “She had a great sense of humour,” says Noel, and the others rush to agree. “She was great to lighten the mood in a room because in this business people can take themselves very seriously and she couldn’t really deal with that. She used to take the piss out of people – ‘they’re so straight!’” “Mischievous”, is how they fondly remember her.

People will also remember her for being vociferously political. Take her 1994 hit, “Zombie”. A response to the death of two children in an IRA bombing, the song was a guttural plea for peace, at once delicate and fierce, with distorted guitars and lyrics about bombs and tanks. Twenty-five years later, it still resonates – particularly following this month’s murder of journalist Lyra McKee in Derry. “It’s terrible to see this type of stuff coming back up again,” says Noel. “The world should have moved on. I was watching the funeral and it’s like going back in time.”

Just as O’Riordan was willing to speak out politically, so too she resisted the sexist pressures of the music industry. The band remember when she returned from a photo shoot where she’d refused to strip half-naked. “It was about the music, her voice and her songs. That was her priority, and she would walk away rather than do anything like that,” Noel says. “But as the years went on, people knew she wouldn’t stand for s**t,” adds Lawler.

One of their favourite memories remains the first time they heard that voice. Back in 1990, they had almost given up on finding a singer to front their band when the quiet, “small girl” from the countryside walked into an audition room in Limerick with a keyboard under her arm and performed in front of the three city boys and their friends.

It was an intimidating first meeting, and they sensed a steely determination in O’Riordan. They gave her the chords for “Linger” and she returned with the vocals complete. It was only a month or two before the band went into the studio, and it was there that they heard the astonishing potential of O’Riordan’s voice. “She was doing backing vocals and soprano stuff so we went, ‘Christ, she can really sing’,” says Lawler. “That’s when it really hit us.”

If a demo tape including “Linger” and “Dreams” got people talking, it was a gig at the University of Limerick attended by 32 music execs that secured them a deal with Island Records. Their debut album Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? was released in 1993, but it wasn’t until “Linger” was picked up by American college radio and the band toured the US that the album became a UK No 1 that would sell more than six million copies worldwide.

From then, things didn’t stop. And what has become a tale too often told of the music industry, the pressure just kept building – until it all imploded at the time of their third album, To the Faithful Departed. They were all depleted, and O’Riordan was anorexic. It was, they all agree, the toughest period of their career.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“She was really, really thin at that point, she wasn’t really eating,” says Noel. “You can see it if you look at videos from that time.” “It was scary,” adds Lawler.

“The fun aspect had gone,” Noel continues. “It started to feel that it wasn’t even our band, that it was being controlled by managers and record companies. We shouldn’t have gone in to do that album, looking back. We should have taken a year off.”

They describe how they were on a 12-month tour when a further year of touring was organised and they naively signed up. By the time they realised they had reached their limit, it was too late to cancel – or at least that’s what they were told by bullying managers. “There would be a lot of scaremongering with managers saying to us, ‘If you cancel this now, you’re going to be sued for millions’, and when you’re 21 or 22 and you’ve come from nothing to that, that’s a scary thought, so you just go ‘OK’. But eventually we did pull the plug.”

O’Riordan was the one who made that decision to take a break, and the rest of the band backed her up. When they pulled out on tour in Australia, their management and record company “went mental”. Angry calls flooded in, but they knew they were doing the right thing. “We were like, ‘No, it’s done. Accept it’”, says Noel. “And nobody did come and sue us.” They’re laughing, but it’s a laugh loaded with regret.

“Dolores was so skinny,” says Lawler, “and she had injured her knee on the second album, and because she was so skinny she had no muscle around her knee, so it gave way. It was just adding up and adding up.”

By the time they reconvened for their fourth album, it was with new managers and a newfound joy to be making music together again.

Experience, they say, has enabled them to spot those industry types to avoid. In contrast, their current label could have pushed for an earlier release to jump on the wake of O’Riordan’s passing, but they gave the band the space to do it the way that felt comfortable.

Where posthumous albums are typically a cynical move by record companies to rake in the cash, In the End is no cut-and-paste assemblage. The album contains the 11 tracks that O’Riordan had been working on with Noel since summer 2017 – and they had set down clear rules. “We didn’t want it to sound cobbled together,” says Lawler. “It wouldn’t do justice to the legacy of the band.”

“It was written as another Cranberries album,” says Noel. “We said to ourselves, ‘If we’re a week into this and it’s not feeling right, we’ll just pull the plug on it.’ We were very aware of that.”

As for the finished album, they feel certain that she’d be “delighted” with it. “Look, we’ll never really know, but we’ve been so careful to be sure that we’re doing the right thing.” They played it to O’Riordan’s family in January at a one-year anniversary mass to mark her death, and “there was nothing but praise for it. You think, ‘OK, we’ve done the right thing.’”

While it is by no means a depressing album, it highlights the challenges that O’Riordan had suffered in recent years. After 20 years with Don Burton, the father of her three children and the former manager of Duran Duran, the couple divorced, and she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Songs such as the title track, and “Lost”, with its dark lyrics “I’m lost without you/ Bring in the night” were the hardest for the band members to work on.

“In the End was sad,” says Lawler. “But it was nice to have some upbeat songs, and to make it a celebration of her life. Because in some ways she’ll always live on in her songs.”

It had been a prolific writing period for O’Riordan, because nobody feels the pull to write more than when engulfed in the grief of loss or heartache (Noel himself has been writing non-stop since his bandmate’s death). “Her way of dealing with things was to write songs about it and you couldn’t keep up with her,” says Noel.

The months before O’Riordan died had been all about looking to the future; Noel recalls his final conversation with her, when she was “excited and pumped” as they discussed dates for touring and recording the album.

“She was in a good place,” Noel says. “And it made it harder for us then, when you get that call.”

The new album feels a fitting ending, not least because of its classic early-Cranberries sound, which brings them neatly back to their beginning. This, they put down partly to the softness of O’Riordan’s vocals, gentler because they were recorded from her apartment in New York. And while they are thrilled with In the End, if there’s one thing they rue, it’s that it will never be toured by them, as The Cranberries, and we will never get to hear the songs morph into their unpredictably dynamic live versions. “There’s a mass of curiosity in your head just wondering what they would sound like live,” says Noel. “But there was one Dolores – she’s got that voice.”

In the End is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments