Why The Beatles split: The true story behind the break-up of the biggest band ever

Paul McCartney’s 1970 press release was the end for the Fab Four, but it had been coming for years, and by the time Yoko Ono was answering for John Lennon in band meetings, the writing was on the wall. Mark Beaumont details the flash-points, fights, and behind-the-scenes tensions that led to the rift that never healed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After eight years that shook the world, redefined music and rerouted popular culture, it took just one word to kill off the best band that ever lived. “Are you planning a new album or single with The Beatles?” Paul McCartney was asked in a press release for his first solo album McCartney, sent to journalists on 9 April 1970. Answer: “No”. And to drive the final nail home: “Do you foresee a time when Lennon-McCartney becomes an active songwriting partnership again?” “No.”

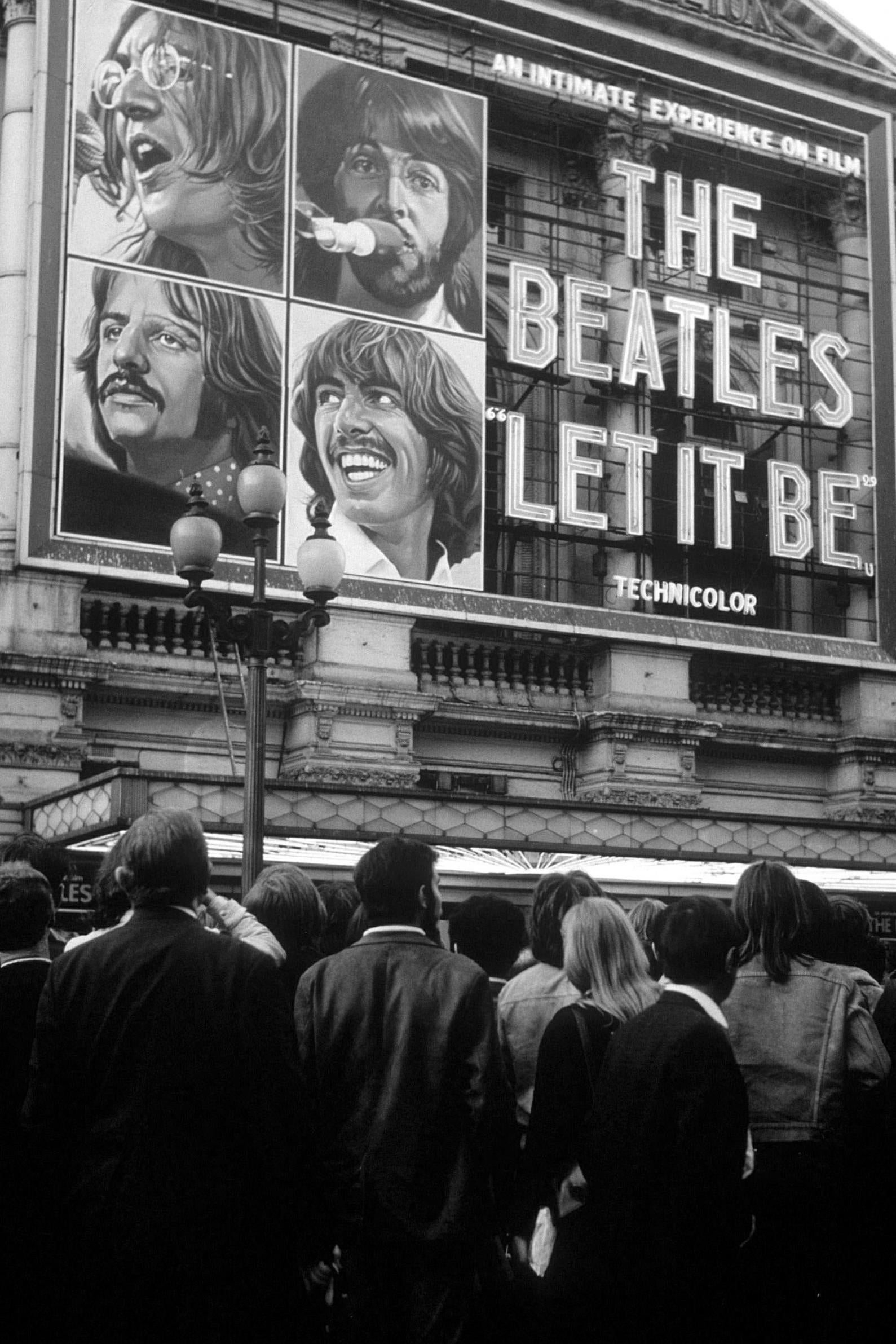

With that, the dream was over. On 10 April, the Daily Mirror ran the front-page headline “Paul Quits The Beatles”, and the media across the world ignited. Fans and reporters gathered outside the offices of Apple Corps at 3 Savile Row, distraught or eulogising. “The event is so momentous that historians may, one day, view it as a landmark in the decline of the British Empire,” reported a CBS News crew from America. “The Beatles are breaking up.”

A generation was plunged into shock and mourning. Not just the screaming hordes of Beatlemania, still barely in their twenties, but the counter-culture dreamers and social activists of flower power who had found mainstream acceptance in the band’s mid-period albums, and the darker rock and psychedelic experimentalists for whom The White Album and Abbey Road were such rich and influential pickings. For almost a decade, through The Beatles and their acolytes, music had owned the world; for many this felt like a full stop not just on the greatest band in history, but on the onward rush of an evolving, revolutionary youth culture.

The Beatles themselves were also shocked. McCartney would later claim that he hadn’t intended his release to be taken as announcement of a split, and was “devastated” at the reaction. George Harrison refused to comment, Ringo Starr responded, “This is all news to me,” while John Lennon quipped: “It was nice to find that he was still alive. Anyway, you can say I said jokingly, ‘He didn’t quit, I sacked him!’”

In reality, the band felt that McCartney had betrayed them by using a break-up they knew was well under way to promote his new record. Under the strains of enormous global success and incredible cultural expectation, The Beatles had become a bristling tangle of ego, insecurity, frustration, hard-drug addiction, spiritual confusion, miscommunication and thinly veiled hostility, their issues exacerbated by the lack of managerial control, encroaching business catastrophe and – yes, to a degree – Yoko.

The writing had been on the wall as far back as 1968 and for Lennon, who’d informed his bandmates of his intention to leave in September 1969, there was the added rancour that it was his band, and his band to destroy.

“I wanted to do it and I should have done it,” he said later. “I started the band, I disbanded it. It’s as simple as that.”

The roots of the split went deep; right back, in fact, to the moment the screams of Beatlemania began to fade.

The cracks appear

By the time McCartney made it official, every Beatle had quit at least once. Harrison was the first to threaten to walk out back in 1966, just four years after “Love Me Do”, insisting that he’d only continue in the band if they stopped touring. As their fame exploded, their live shows had become messy and inaudible above the screaming. McCartney had to be convinced, and for Lennon it marked the beginning of the end. “That’s when I really started considering life without The Beatles,” he said. “What would it be? And that’s when the seed was planted that I had to somehow get out without being thrown out by the others.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

His bandmates were watering their own seeds of resentment. 1967’s Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, their last truly unified work, captured the essence of psychedelia and would come to define the Sixties, but as it was very much McCartney’s concept its success also marked the point where the band’s power structure shifted. From that point, McCartney would often press for and direct projects of his own invention, such as that year’s Christmas TV special and album Magical Mystery Tour, to the point where the rest of the band began to resent his controlling – and sometimes condescending – attitude.

It particularly irked Harrison, who was struggling with feeling underappreciated. His songwriting was coming on in leaps and bounds, as evinced by his three fantastic contributions to Revolver in 1966 – “Taxman”, “Love You To” and “I Want to Tell You” – yet the Lennon-McCartney partnership had such an iron grip on the band that he felt his contributions weren’t getting a fair hearing. “We’d have to record maybe eight of theirs before they’d listen to mine,” he said.

Such divisions were compounded by the band’s trip to the Indian ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in February 1968. While supportive of Harrison’s burgeoning interest in eastern philosophies and keen to ditch drugs in favour of the biological narcotic of transcendental meditation, each had their own reaction to the Maharishi’s training course of lecture and meditation. Starr left just 10 days in, claiming he couldn’t eat the food and missed his kids. McCartney lasted a further week, largely using the retreat as a very productive writing session, much to Harrison’s annoyance.

Harrison and Lennon stayed on for several weeks more, but Lennon became frustrated that the Maharishi’s methods were not giving him any grand metaphysical answers to his problems. If anything, India worsened them – during his stay he became estranged from his wife Cynthia, sleeping in a separate room and sneaking away to receive daily telegrams from Yoko Ono, whom he’d met in 1966. When rumours of the Maharishi making sexual advances on some of the women at the ashram angered Lennon and Harrison enough to make them leave, Lennon spent a drunken flight home detailing his infidelities to Cynthia.

The Beatles returned from India with 40 new songs, but a changed group. Their meditation practices had made them more insular as songwriters and highlighted their personal incompatibilities. John was angered and betrayed by the experience, more bereft of answers than ever and soon to begin dabbling in heroin to numb his pain, just as McCartney started fuelling his recording routine with cocaine. Never a recipe for creative synchronicity at the best of times.

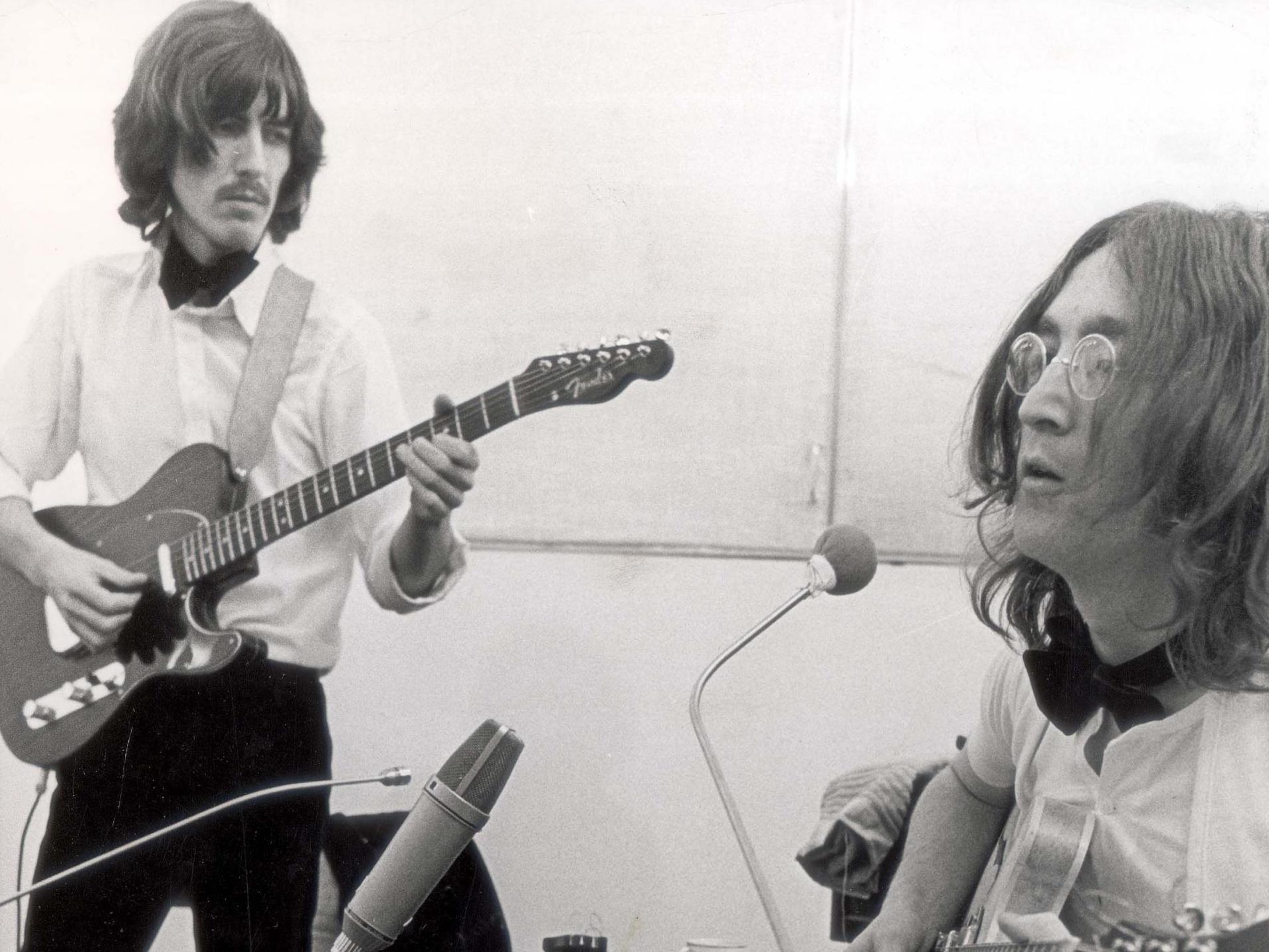

And these were some of The Beatles’ worst times. When they reconvened at Abbey Road to record The White Album in May 1968, they were so personally and creatively at odds that they often recorded their songs in three separate studios. Lennon disliked McCartney’s saccharine “granny” songs, and McCartney was equally un-taken by Lennon’s brittle primal screams and arthouse experiments. Each songwriter used the rest of the band essentially as backing musicians, with McCartney particularly dismissive of his bandmates’ tracks: “We’d take hours on his songs then just knock off ours,” Lennon would say.

The sessions were fraught – Lennon stormed out of the recording of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” from sheer boredom, McCartney berated producer George Martin, and engineer Geoff Emerick quit due to the knife-edge atmosphere. McCartney would dub the record “The Tension Album” and comment, “There was a lot of friction during that album. We were just about to break up, and that was tense in itself.” Lennon argued, “The break-up of The Beatles can be heard on that album.”

Into this slow-punctured wheel, enter Yoko Ono, a near-silent stick in the spokes. Cynthia had returned home early from holiday to find Lennon and Ono together, the knell on their marriage, and from the recording of “Revolution #1” at Abbey Road Ono was a constant presence. Lennon intended her to become a de facto Beatle, contributing to the sessions; she would accompany him everywhere, even sitting beside him on the floor as the band played, quietly muttering suggestions. Ono became a barrier both to Harrison’s bond with his old LSD buddy John and the musical intuition between Lennon and McCartney, who would never collaborate as closely again. Her musical influence caused friction too. “It was terrifying when Paul confronted John over ‘Revolution #9’, accusing him of sabotaging The Beatles,” a witness said. “Lennon didn’t respond at all.”

On 22 August, The Beatles split for the first time. Starr, feeling unvalued and peripheral, left the band over McCartney’s relentless criticism of his drumming on “Back in the USSR”. When the band begged him to return after a two-week break in Sardinia, Harrison had covered his drum kit in flowers. It would only be a matter of months, however, before Harrison would make his own bolt for the door.

The business disasters

Behind the scenes, the empire was teetering. Since the death of manager Brian Epstein from an accidental sleeping pill overdose in August 1967, the band were left to run their Apple Corps business themselves, for which they were woefully unprepared. Initially founded in 1967 as a tax shelter, Apple was intended to discover new musical talent as well as delve into publishing, real estate, electronics, retail and film. But in the hands of four doped-up hippies who thought themselves rich beyond all concern and considered the idea of the company making profit as a bread-headed betrayal of their ideology, Apple swiftly became a financial sinkhole.

Salaries were high, the cost of buying 3 Savile Row exorbitant and the business a free-for-all. Harrison referred to it as “rooms full of lunatics… and all kinds of hangers-on” and accountants quit over the band’s messy personal finances. By 1969 it became clear a firmer hand was needed on the tiller of both band and Corps.

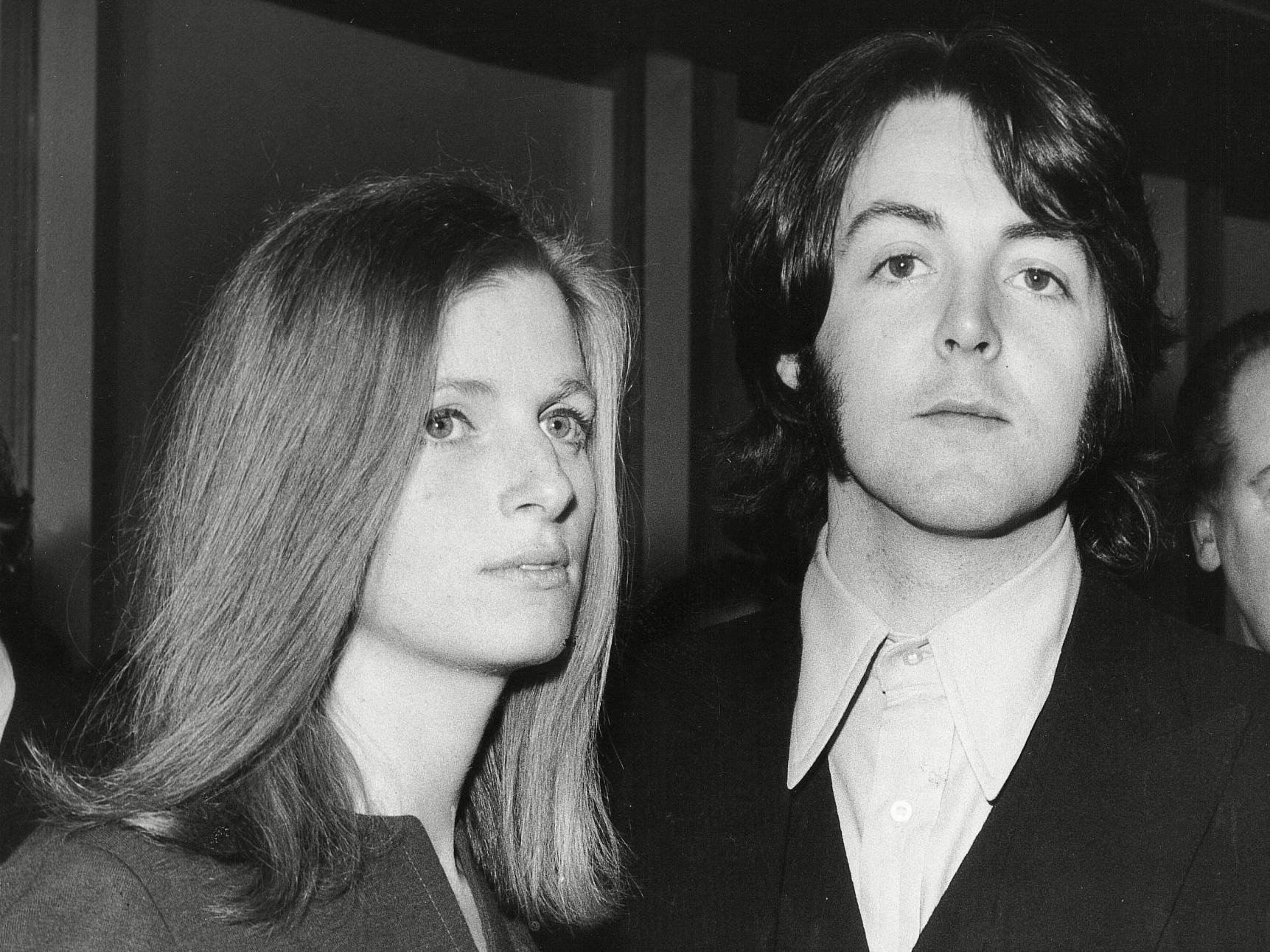

McCartney was keen to employ his future wife Linda’s father and brother, entertainment lawyers Lee and John Eastman, but his bandmates were wary of giving him even more control over the band. Lennon and Ono, meanwhile, had been seduced by Allen Klein, the streetwise manager of The Rolling Stones who had been desperate to get his hands on The Beatles. He had a reputation for tough negotiating but was under investigation by the US financial authorities – Mick Jagger even sent McCartney a note warning him not to go near Klein. Nonetheless, Lennon was flattered into signing Klein as his financial representative on their first meeting, and as Klein baited the Eastmans in fraught meetings, Starr and Harrison were convinced to take him on as manager. McCartney reluctantly accepted the group decision, but it drove a further wedge between himself and Lennon, and he refused to put his signature on Klein’s contract. It would prove his escape route from the band.

The flashpoints

The desire to “get back to where you once belonged” wasn’t just shared by Jojo and Sweet Loretta Martin, it was a subliminal mission statement for Let It Be. In the hope of rekindling the band’s old Hamburg cohesion, McCartney suggested they return to their rock and blues roots for a project provisionally entitled “Get Back”. The idea was for director Michael Lindsay-Hogg to film the rehearsals for a live show consisting of new material, to be performed at London’s Roundhouse on 29 January 1969. The end result, however, was The Beatles pretty much breaking up on camera.

When sessions began on 2 January, working an un-Beatles schedule of nine-to-five on a cold Twickenham soundstage, Lennon, Starr and Harrison were unsure about the whole idea, while the “workaholic” McCartney was directing the rehearsals like another of his personal projects. “Why are you here?” he asked the band. “I’m here because I want to do a show, but I don’t see an awful lot of support.”

By now Lennon and Ono were on heroin and communicating via the wordless practice of “heightened awareness” – if a decision was needed, Lennon would stay silent and let Ono speak for him, destroying any real band interplay. The terseness of the recording spilled onto celluloid: “I’ll play whatever you want me to play, or I won’t play at all if you don’t want me to play,” Harrison snapped at McCartney during a frayed session for “I’ve Got a Feeling”. “Whatever it is that will please you, I’ll do it.”

Ostracised from Lennon, patronised by McCartney and detesting the idea of the live gig, Harrison was next to quit the band. After a fight with Lennon on 10 January over Lennon speaking publicly about Apple’s looming bankruptcy – George Martin would later claim that punches were thrown and “hushed up” – Harrison left the band on film. “I’m out of here,” he said as he packed up and left, “put an ad in and get a few people in. See you round the clubs.”

An initial attempt to patch up their differences at a meeting at Starr’s house two days later ended badly when Harrison again stormed out when Ono kept speaking for Lennon. Sessions for Let It Be, as it would be renamed, only resumed two weeks later at Savile Row on Harrison’s insistence that there would be no major concert. Instead, the band famously played their last show together on the roof of Apple Corps on 30 January, and even then Harrison had last-minute reservations. “George didn’t want to do it, and Ringo started saying he didn’t really see the point,” said Lindsay-Hogg. “Then John said, ‘Oh, f*** it – let’s do it.’” Forty minutes later, as the police raided the rooftop, Lennon closed the last ever Beatles performance with the quip, “I hope we passed the audition.”

It was perhaps the old spark of playing live, clearly visible in the grins passing passed across the rooftops of W1 that afternoon, that encouraged The Beatles to make one more album together. They reconvened in July to record Abbey Road, individually inspired (particularly Harrison) but with no impasse in sight. Lennon initially wanted his and McCartney’s songs separated on each side of the album, and insisted on having a bed installed in the studio for Ono. When McCartney missed one session, Lennon broke into his house and damaged a painting. “The three of them were a little bit scared of him,” EMI engineer Phil McDonald said, and biographer Barry Miles agreed: “The other Beatles had to walk on eggshells just to avoid one of his explosive rages.”

The Beatles last played together on 18 August, fittingly recording “The End”. With Harrison contributing two of his greatest songs in “Something” and “Here Comes The Sun” and McCartney’s concept of linking songs together into a spectacular suite stretched over side two, they’d pulled a masterwork from wreckage. Abbey Road was the culmination of eight years of inspired exploration, an album that The Beatles deserved to bow out on. Instead, their end would become more of a scramble for the wings.

The last months

On 8 September 1969, McCartney, Lennon and Harrison met to decide The Beatles’ future, and vent long-held frustrations. With a glut of material, both Harrison and Lennon were tired of having to fight McCartney for the chance to record their songs so Lennon suggested a more democratic approach to the next album – an equal-rights songwriting split of four songs each from Lennon, McCartney and Harrison and two from Starr. The rapturous reception given to his Plastic Ono Band show at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival on 13 September changed Lennon’s mind though – on the plane home, in another airborne revelation, he resolved to leave the group.

At Apple HQ on 20 September, he let loose, blaming McCartney for making him doubt his songwriting abilities and stifling his voice until he’d lost the will to fight for his songs. When McCartney suggested that touring again might rejuvenate their magic, Lennon snapped “I think you’re daft. I wasn’t going to tell you, but I’m breaking the group up. It feels good. It feels like a divorce.”

“Our jaws dropped,” McCartney said; the news shocked everyone. Ono hadn’t even picked it up on their psychic airwaves. “We went off in the car,” she revealed later, “and he turned to me and said, ‘That’s it with the Beatles. From now on, it’s just you, OK?’”

A new, improved royalty deal with Capitol records was due to be signed, so the band convinced Lennon to keep the split secret. As Lennon talked up the possibility of a new Beatles tour in the press over the coming months, and told a Danish journalist, “We’re not breaking up the band, but we’re breaking its image,” his bandmates speculated privately about whether Lennon was having “one of his flings” and would change his mind.

In his remote Scottish family farm, a distraught McCartney turned to drink, only crawling from the bottle when he found the spirit to record his solo album McCartney. Phil Spector’s new, lushly orchestrated production on his plaintive piano ballad “The Long and Winding Road” horrified him, but with his communication with Klein having entirely broken down he wasn’t able to insist on changes before Let It Be was pressed. The final straw came when Starr was sent to his house with a letter from the band insisting he move his album’s release date to make way for Let It Be – McCartney flew into a rage and threw Starr out. The next thing the band knew, McCartney had split the band by press release.

Recriminations were instant. Fans flocked to condemn McCartney for splitting the band, and he rushed to defend himself in the press: “Ringo left first, then George, then John. I was the last to leave! It wasn’t me!” The band’s press officer released a statement citing McCartney’s issues with Klein and claiming The Beatles “do not want to split up, but the present rift seems to be part of their growing up… at the moment they seem to cramp each other’s styles… They could be dormant for years.” Both Lennon and Harrison spoke of the band regrouping – “It could be a rebirth or a death,” said Lennon. “It’ll probably be a rebirth” – and when McCartney called Harrison as he set about trying to extricate himself from Apple, Harrison told him, “You’ll stay on the f***ing label. Hare Krishna.”

In December 1970, with his bandmates still claiming their differences could be resolved, McCartney resorted to the courts to dissolve the band in litigation which would only formally wrap up The Beatles on 9 January 1975. By then the individual Beatles were deep into successful solo careers, and their legacy and legend had long outlasted the scrappiness of their break-up. Yet many early solo records were steeped in regret and, to this day, The Beatles split feels like an avoidable tragedy, the saddest example in rock history of the suffocating effects of untameable talent and success. And yes, they passed the audition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments