Crazed girls, loose bladders, and JFK: How The Beatles defied the odds to break America

Sixty years ago the Fab Four touched down in the US, greeted on the tarmac by fainting fans and police cordons – but stateside success wasn’t always a sure thing. Mark Beaumont chronicles the extraordinary, inimitable series of chance events that secured these scouse mop-tops a permanent place in America’s heart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Word of the encroaching invasion rang out across the airwaves of New York City. “The Beatles are coming!” yelled DJs and newscasters, echoing the slogan that had been emblazoned across badges, posters, car stickers and newspaper ads for weeks prior. Hundreds of reporters and cameramen descended, police formed cordons, and merchandise companies handed out sweatshirts. Screaming teenagers lined the balconies and walkways of JFK airport hoping for a glimpse of the mop-topped pop sensation from across the Atlantic who, 60 years ago today, broke America – before they’d even set foot on it.

“There were millions of kids at the airport, which nobody had expected,” Paul McCartney said in 1995’s Anthology documentary. “We heard about it in mid-air. There were journalists on the plane, and the pilot had rung ahead and said, ‘Tell the boys there’s a big crowd waiting for them.’ We thought, ‘Wow! God, we have really made it’… I remember the great moment of getting into the limo and putting on the radio and hearing a running commentary on us. ‘They have just left the airport and are coming towards New York City…’ It was like a dream. The greatest fantasy ever.”

“What got the kids to the airport were the radio stations promoting it,” says US Beatles expert Bruce Spizer, author of The Beatles are Coming: The Birth of Beatlemania in America. “When The Beatles’ plane took off in London, the New York radio stations were [narrating it] and kids are thinking ‘I’m gonna cut school.’” More than 3,000 kids skipped class to see The Beatles touch down that afternoon.

The image of John, Paul, George and Ringo waving from the top steps of Pan Am Yankee Clipper flight 101 at 1.20pm on 7 February 1964 is among the most iconic in rock’n’roll history. Not for the bemused realisation on their faces that they had truly made it but for its impact on the hopes, dreams and possibilities of generations to come. That picture of the moment Beatlemania hit the States would come to encapsulate the ultimate fantasy and ambition of every dreamer they inspired to pick up a guitar, and thousands more thereafter. To break America, amid pandemonium.

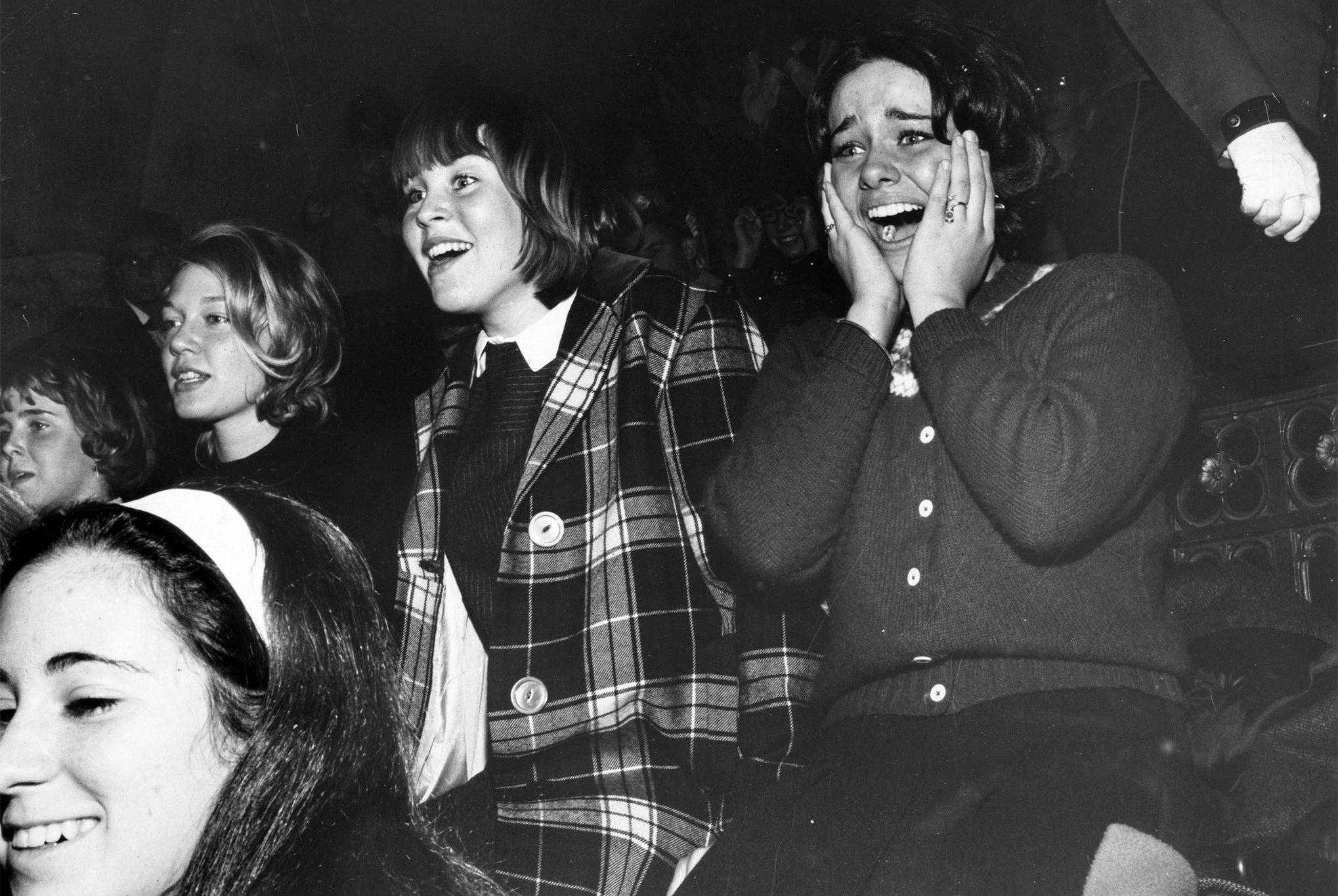

Yet this was a seismic moment in pop history that, like so much of The Beatles’ career, would prove impossible for later UK acts to replicate – even those that would manage to break America, such as The Rolling Stones and the rest of the subsequent British Invasion, or later Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, The Prodigy or Coldplay, would fail to inspire scenes of such bladder-loosening Fabslust. Partly because the virulent US strain of Beatlemania was the result of an extraordinary, inimitable series of chance events.

It’s easy in a globally linked, instant access 2024 to assume that pop songs as timeless as “She Loves You”, “Please Please Me” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” would naturally have taken off in the UK and America simultaneously, or that The Beatles’ genius would inevitably have conquered the States by the time of, say, Help!. The latter may well be true but for a serious minute in 1963, The Beatles came close to being written off in the USA.

Six decades of rock’n’roll evolution, indeed, were almost scuppered by some cloth ears in situ at Capitol Records. As the US subsidiary of The Beatles’ umbrella label EMI, they declined to release both “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me” in America in 1963; an A&R exec called Dave Dexter couldn’t understand what all the Cavern-cramming fuss was about in the UK. Under pressure from producer George Martin, an attorney named Paul Marshall shopped “Please Please Me” around other uninterested major labels before signing The Beatles a five-year deal with Vee-Jay, a tiny R&B and gospel label in Chicago. Vee-Jay had recently scored a Top Five hit with another Capitol reject – Frank Ifield’s “I Remember You” – but, backed with limited airplay, shifted only 5,000 copies of “Please Please Me”.

A second Vee-Jay single, “From Me to You”, fared fractionally better because the much more famous Del “Runaway” Shannon was releasing a cover of it at the same time. And when Vee-Jay stopped paying royalties, sinking the deal altogether, The Beatles landed back in Dexter’s lap like a stray cat with mange, this time singing “She Loves You”. “He listens to ‘She Loves You’ and he listens to ‘I’m Confessing’ by Frank Ifield,” says Spizer, “decides one of these is going to be a big hit, and has Capitol take out a full-page ad in Billboard for Frank Ifield’s ‘I’m Confessing’.”

“She Loves You” eventually found a home at Philadelphia’s minuscule Swan Records, only to be classed a miss by local TV star Dick Clark’s music show American Bandstand. The song followed its forebears into obscurity’s chasm. “It’s not happening in the States,” says Spizer. And Dexter, true to form, decided that releasing The Beatles’ next single “I Want to Hold Your Hand” would just be setting money on fire. The band’s frustrated manager Brian Epstein, however, went over Dexter’s head, calling the president of Capitol, Alan Livingston, to convince him to give the songs a spin.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“Livingston tells Dexter, ‘Look, can you send me a couple of Beatle discs up here?’” Spizer explains. “Dexter says, ‘Alan, they’re a bunch of long-haired kids, they’re nothing.’ And Livingston says, ‘Just the same, I want to hear it.’ And he listens to ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ and he gets it.” When Livingston called Epstein back to confirm the release, Epstein’s chutzpah stretched to insisting that Capitol couldn’t have the song unless they spent a then-monumental $40,000 on promotion.

With Capitol finally behind a Beatles single release, scheduled for mid-January 1964, the US media sat up. News crews from CBS, NBC and ABC were dispatched to a Fabs show in Bournemouth in November 1963 to film Beatlemania in action; the low-rated CBS Morning News ran a four-minute story on the phenomenon on 22 November, with Walter Cronkite planning to give the piece a higher-profile repeat on his Evening News show that night.

Then, a few hours after the morning broadcast, shots rang across Dealey Plaza in Dallas, puncturing history’s pages. The Beatles were shunted from Cronkite’s news cycle by a national crisis and, for the coming weeks, four waggle-headed lads from Liverpool seemed a world away from a country in shock and grief. There The Beatles’ American ambitions might have perished, gunned down alongside America’s sweetheart president, John F Kennedy.

The youth of America, though, would not be robbed of their cultural coup. When Cronkite decided, a fortnight later, that the US was in need of some light relief, he ran the Beatles footage – and in doing so lit the fuse of global Beatlemania. Somewhere in Washington DC, a 15-year-old girl called Marsha Albert was so enraptured by the performance she saw on CBS that she wrote a letter and mailed it to her local DJ, Carroll James at WWDC-AM. “Why can’t we have music like that here in America?” she asked, begging him to play “I Want to Hold Your Hand” on the radio. Through airline contacts, James acquired an import copy from the UK and began playing the song; the switchboard exploded – and not just with fans desperate to hear the track again. “[Capitol] get their attorney to call them up and say, ‘Stop playing the record’,” says Spizer, “And the station says ‘Are you nuts? It’s a hit!’”

I’ve heard that while the show was on, there were no reported crimes, or very few. When The Beatles were on ‘Ed Sullivan’, even the criminals had a rest for 10 minutes

Recognising a wildfire when they saw one, Capitol moved the release of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to Boxing Day. Across the holiday period, the track flew to No 1 across the nation. “Kids in those days weren’t playing video games,” says Spizer. “They were listening to the radio. They weren’t in school. They had Christmas and Hanukkah money, and mummy and daddy could take them to the record store.”

Still sitting on the rights to those earlier singles, Vee-Jay and Swan cashed in with re-releases of “Please Please Me” and “She Loves You” while Ed Sullivan started plugging the band’s forthcoming appearance on his show an unprecedented month upfront. Meanwhile, Capitol started throwing their $40,000 promo budget directly at pop consumers: “The Beatles Are Coming!” read billboards, buttons and even a specially printed newspaper of Beatles news, distributed at schools. By the time the band landed at JFK in February, their singles were hogging the top three places of charts nationwide and both Vee-Jay and Capitol had rush-released albums. The Beatles were flying into a whirlwind.

Thankfully, they exceeded the hype. During chaotic press conferences, The Beatles won over a condescending press with knockabout charm and off-the-cuff wisecracks. What did they think of Beethoven? “Great, especially his poems,” quipped Starr. Would they sing something? “We need money first,” snapped Lennon. Were they going to get haircuts? “I had one yesterday,” Harrison deadpanned. How did they find America? “Turned left at Greenland,” Starr retorted, a line so good that Lennon would steal it for himself in their first movie A Hard Day’s Night.

The good-natured yet rebellious snook that The Beatles cocked at the media’s attempts to mock them – their Liverpudlian accents, their collar-threatening hair – exposed the establishment’s outdated conformist attitudes and made the band look like carefree social emancipators, freedom sprouting from every follicle.

“They had a way of thumbing their nose at authority and authority laughing along because authority wasn’t getting it, but we got it,” says Spizer. “We weren’t in a global community. They were from across the pond, this foreign land, England, plus some port town, Liverpool. They had this radically long hair, they looked different, they sounded different with the British accents.” The argument that, after several months of grieving JFK, a devastated America was primed to fall for these cheery mop-tops doesn’t hold water with Spizer. “Did it cheer the nation up? Of course, it did, but it was not cause and effect. We fell for The Beatles because the music was great, and The Beatles were exciting to us.”

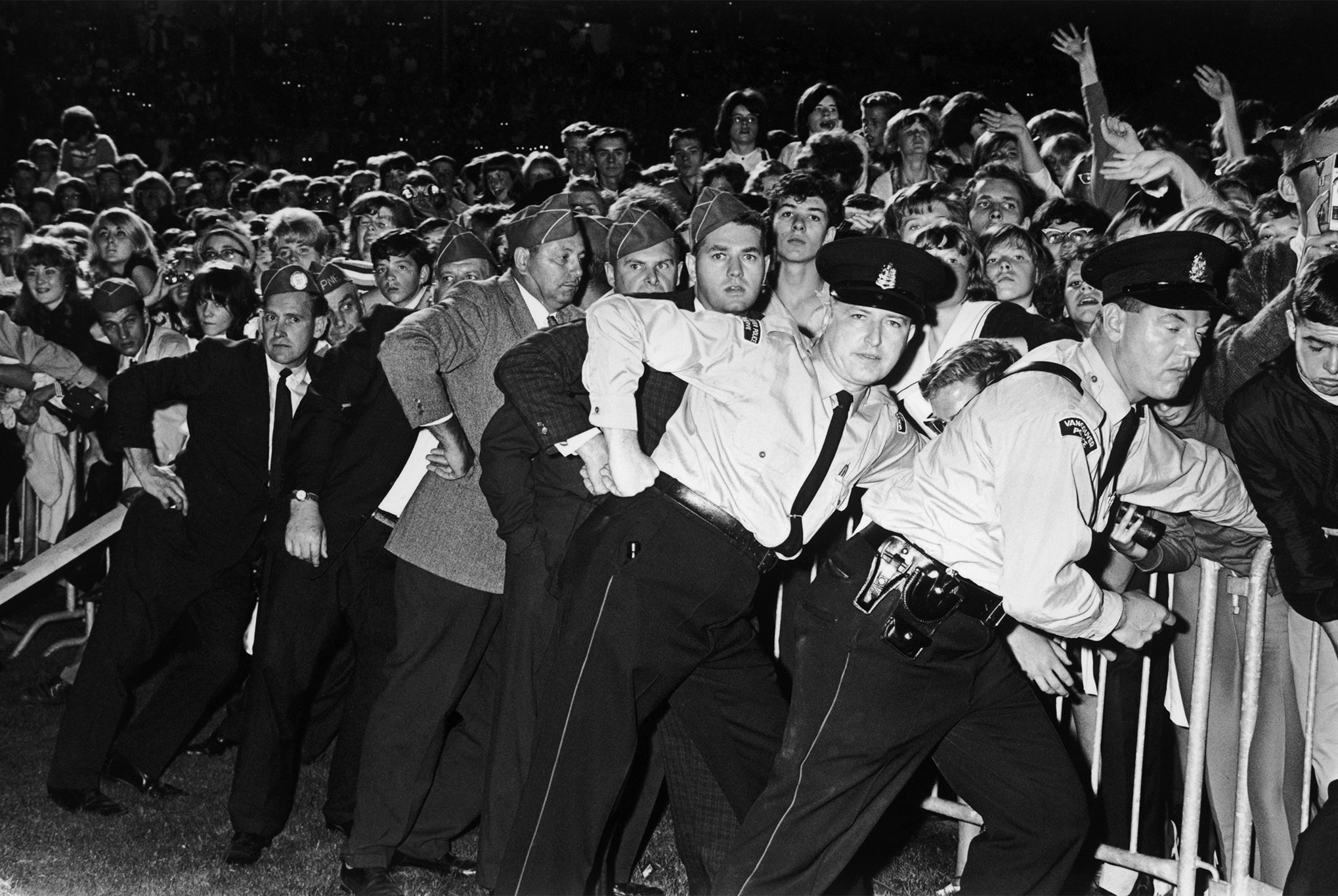

That fever chased The Beatles across the east coast. A recent National Portrait Gallery exhibition including McCartney’s own photographs from the trip, Eyes of the Storm, gave a Beatles-eye view of fans pursuing their car along New York City’s West 58th Street and of screaming hordes held back by mounted policemen outside their Plaza Hotel. Visitors to their 10-room, 12th-floor presidential suite included The Ronettes; Elvis sent a telegram. Their legendary appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show on 9 February – booked back when the band were floundering nobodies in the States– drew a record-breaking 73 million viewers, still one of the biggest US TV audiences of all time.

“I’ve heard that while the show was on, there were no reported crimes, or very few,” Harrison said in Anthology. “When The Beatles were on Ed Sullivan, even the criminals had a rest for 10 minutes.” “All these kids are now grown-up, and telling us they remember it,” added McCartney. “It’s like, ‘Where were you when Kennedy was shot?’ I get people like Dan Aykroyd saying, ‘Oh man, I remember that Sunday night; we didn’t know what had hit us – just sitting there watching Ed Sullivan’s show’.”

Spizer was eight years old when the Fabs dazzled him that night. It was all he and his friends could talk about. “Everybody watched it,” he says. He particularly applauds the perfectly concocted setlist: “All My Loving, “She Loves You”, “I Want to Hold Your Hand”, “I Saw Her Standing There” – and “Till There Was For You” for “all the moms and dads”.

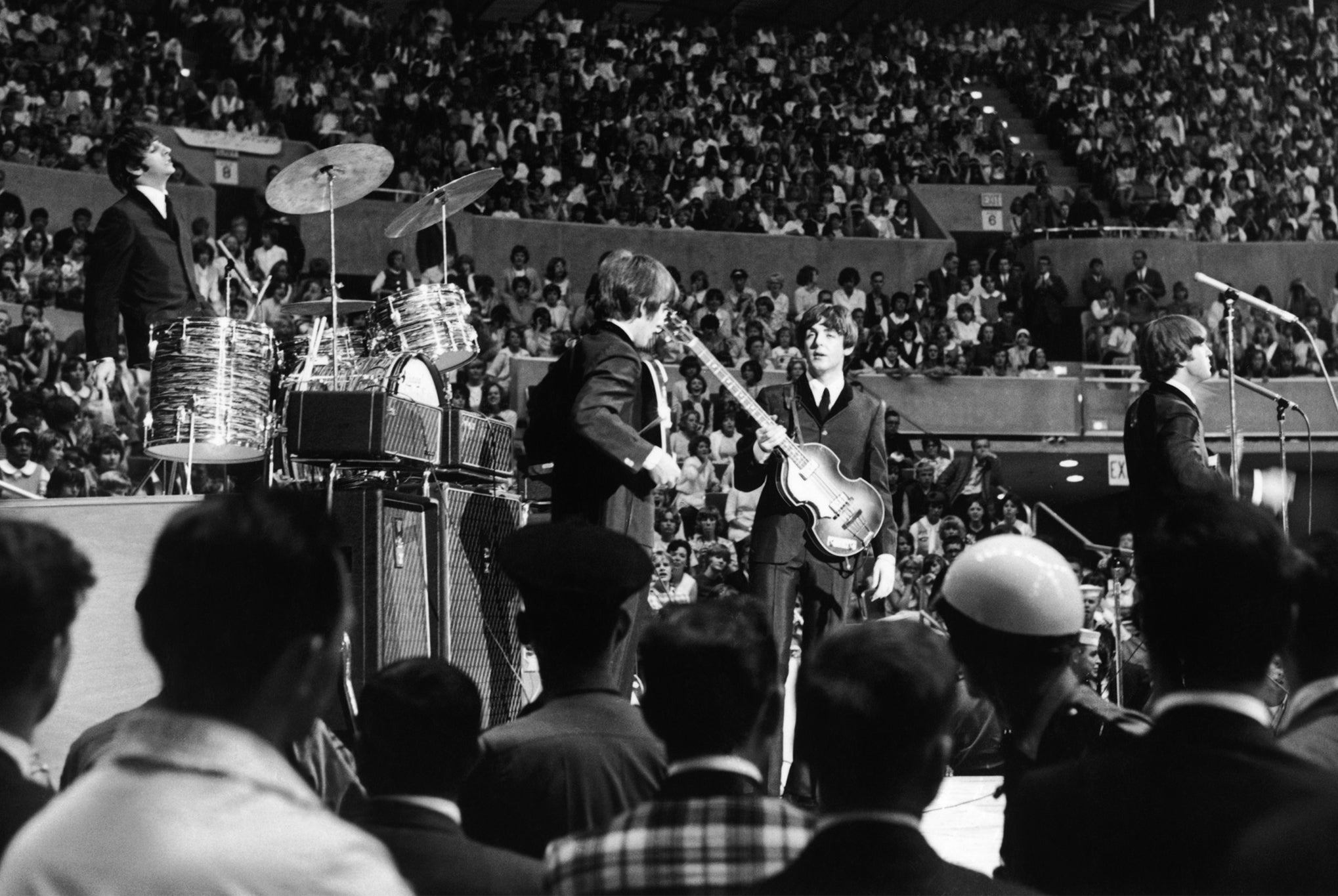

When a snowstorm scuppered the band’s plans to fly to their first US show, playing to 8,000 fans at the Washington Coliseum boxing arena, thousands of them turned up at Union Station to meet them from their high-security train. “We almost got killed when we got off the train,” said DJ Murray the K, who was travelling with the band. “Some 10,000 kids had broken through the barriers. I remember being pinned against a locomotive on the outside, and feeling the life going out of me … George looked at me and said, ‘Isn’t this fun?’” Less enjoyable was the show itself, where the band were pelted with jelly beans by fans who’d read they liked them, and an aftershow reception at the British embassy where they were pawed at like animals. One of the assembled dignitaries cut off a lock of Ringo’s hair. “I walked out of that. Swearing at all of them and I just left in the middle of it,” Lennon said.

At Penn Station, 10,000 screamers welcomed them back to New York for two shows at the auspicious Carnegie Hall; after the second, promoter Sid Bernstein offered Epstein $25,000 to play Madison Square Garden the following week, knowing he’d fill it. Epstein politely declined. By the time The Beatles reached Miami for some downtime ahead of a second Ed Sullivan recording there, such was the national hysteria around them that they were granted random audiences with the likes of Muhammad Ali and reporters were caught trying to smuggle themselves onto their boat tours.

When The Beatles flew home two weeks after their historic arrival, they had no idea that the culturequake they’d triggered there would dominate music for six decades to come. UK labels had been abruptly awoken to the idea of America as a land of unimaginable opportunity. It was a revelation that sent a tsunami wave of British Invasion acts across the pond over the coming years – The Stones, The Kinks, The Who, Small Faces – arriving Stateside to similar fanfare, there to feed America’s insatiable hunger for scruff-haired British beat groups roughing up American blues and rock’n’roll. With an unwholesome rebel energy and exotic Old-World allure, these types were far removed from the slick-haired hip-swivellers of heartland USA, and American teens swallowed them whole.

Not only did The Beatles’ US success help to inspire 1960s counterculture on both sides of the Atlantic – and crown a pantheon of UK rock establishment bands that would endure to this day – it also made Britain a musical behemoth of equal standing with America. These two cultural titans would ping-pong the zeitgeist across the Atlantic for decades. They gave us Dylan, The Beach Boys, The Monkees, and Hendrix; we gave them Led Zeppelin, heavy metal, and the giants of prog. They gave us New York punk; we gobbed it straight back in their face. They gave us all-American slacker grunge; we responded with the bright-eyed and twitchy-nostrilled Britpop – something of a British Invasion tribute, really, as if to remind America who was boss.

There were less welcome effects, too. That aeroplane steps photo was pivotal in instigating a dynamic in rock music whereby boys played guitars to the wild adulation of girls, a misguided social “norm” that became so deeply embedded in the music industry that we’re only now beginning to untangle it. Every Reading & Leeds bill short on women is a direct – albeit inadvertent – result of Ringo turning left at Greenland.

But that shouldn’t detract from the impact of the moment, unrepeatable in the atomised and industrialised musical landscape of 2024. “Could a British band come to the US and have this kind of impact today?” Spizer asks. “No, they could not. No matter how great they could be. Radio is too segmented now. We had Top 40 radio, which meant most people were hearing The Beatles all at the same time. But today, people are going to listen to the type of music that they most want to listen to. So, I don’t think you ever would get that kind of exposure again that The Beatles got.”

It was a moment when music united the world – a hit we’ve been chasing ever since.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments