‘Stairway To Heaven’ at 50: The song that ushered in the era of the guitar hero

Fifty years ago, Jimmy Page played his new, eight-minute opus for an underwhelmed Belfast audience. Soon, it would be one of the biggest songs in the world. Mark Beaumont looks back at the song, its origins and its legacy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Jimmy Page strapped on a double-necked guitar at Belfast Ulster Hall on 5 March 1971, the audience no doubt thought they were about to be bombarded with twice the rock. They’d already been savaged by the live debut of blues Cerberus “Black Dog”, their first taster from Led Zeppelin’s forthcoming fourth album, and were eager for the world’s hottest hard rock band to keep the pedal to the formative heavy metal.

Then Page plucked out a gentle pastoral arpeggio redolent of arcadian glades, medieval minstrels and all manner of nonny-nonnyness, a refrain crying out for classical recorder accompaniment. Robert Plant’s lyrics only enhanced its arcane air: “There’s a lady who’s sure all that glitters is gold/ And she’s buying a stairway to heaven…”

Eight minutes later, the song ended to polite applause. “They were all bored to tears waiting to hear something they knew,” said bassist John Paul Jones.

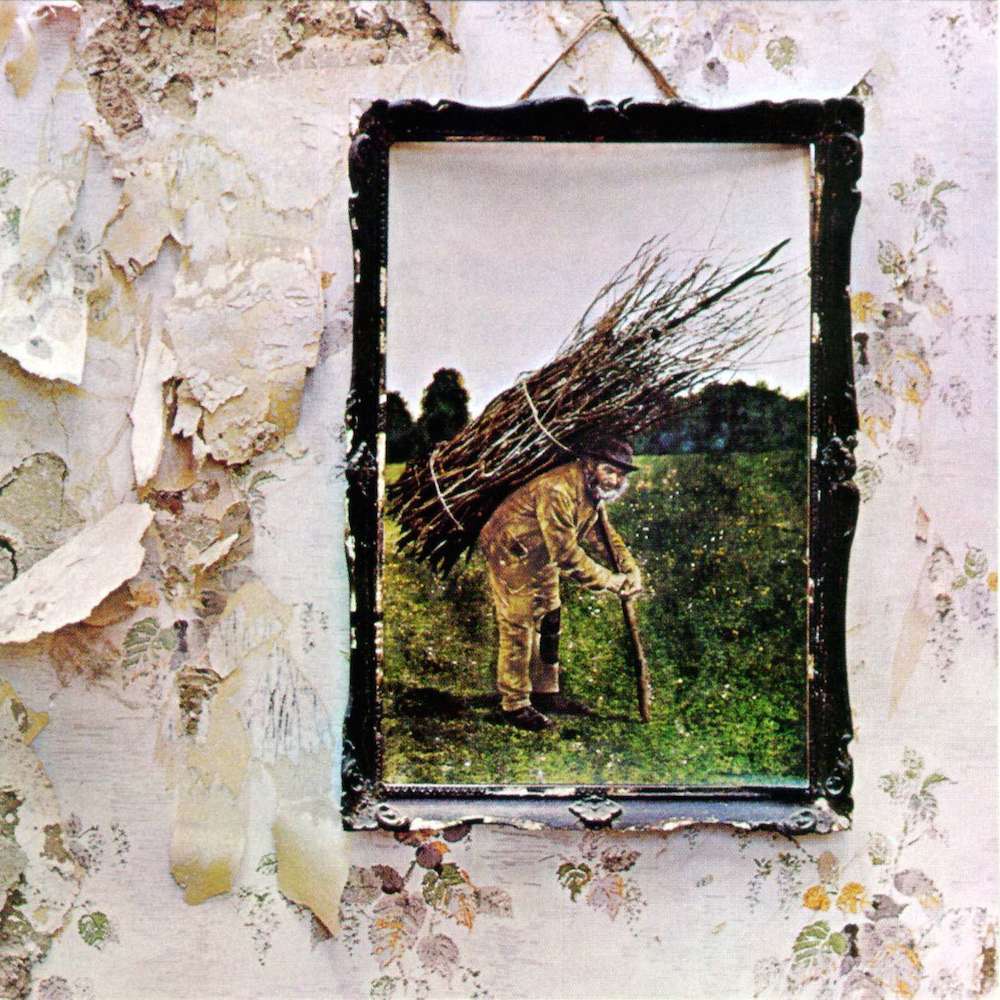

Fifty years ago this week, history passed the Union Hall crowd by on their way to the bar. By the end of that year, “Stairway To Heaven” was the most requested song ever on American radio and was proving itself crucial in sending Led Zeppelin IV (as the untitled 1971 album is commonly known) towards 37 million sales and Zeppelin themselves to the very peak of the Seventies rock pantheon. The song might have better been titled “Express Lift To Superstardom”.

For decades it would hover near the top of Best Song polls, and by 2000 it had clocked up three million radio plays, totalling 45 years’ worth of airtime. Its influence was monumental, not just on the Seventies rock and prog acts that would swiftly adopt its expanding, accelerating template – Genesis’ “Supper’s Ready”, Aerosmith’s “Dream On” and Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” are among the many tracks that sloped slyly up Zeppelin’s back staircase – but on their legions of descendants across rock’s panorama, from Metallica to Foo Fighters via Pearl Jam and, in tongue-in-cheek tribute, Tenacious D. It was the song that raised the perception and ambition of early hard rock from the primal to the profound and became such a prevalent byword for muso guitar worship that guitar shops would hang “No Stairway” signs in their try-out areas.

“Stairway…” had a fittingly rural origin. Retreating with Plant to a remote Welsh cottage called Bron-Yr-Aur in the wake of Led Zeppelin’s 1970 US tour, Page wrote the introductory guitar part for a sweeping, layered piece, building from acoustic and organ to an electric climax, that he’d been talking about in the music press before he’d even written a note. “He had the idea to have an epic song to replace ‘Dazed and Confused’ in concert,” says Jean-Michel Guesdon, co-author of Led Zeppelin: All The Songs. “Something that evolves slowly, while increasing crescendo and ending in apotheosis. It was planned, it wasn’t an accident.”

It was also intended to expand the band’s appeal beyond the headbanging boys’ club. “Page did go out of his way to create a song that women would like,” says Chris Salewicz, author of Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography. “He was very conscious that Led Zeppelin was kind of boys’ c**k rock and wanted something that had a more pastoral and presumably hummable tune.”

After further work on the song’s structure at his Pangborne home, Page presented the song to his bandmates at their Headley Grange studio in Hampshire to a bewildered response. “It’s not just one of those things where it goes verse-chorus-verse,” he told The Guardian in 2014. “It was tricky because it had sections, but they didn’t repeat exactly the same each time… The thing I was very keen to establish was that the whole thing would keep moving in tempo and intensity.”

“It’s a very complex song,” says Salewicz, “and it goes against what all popular music is supposed to do in the way it speeds up about two-thirds of the way through. That went against everything that Page had learnt in his years of playing sessions – that there was a strict format and you weren’t supposed to speed a song up. But that’s part of why it works.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Page would liken the finished track to a rising adrenalin flow culminating in an orgasm, and the emotional pull of the music combined with Plant’s mystical conundrum lyrics, written in a eureka moment by a Headley Grange fireside, to make the song an experience for both body and mind. Supposedly inspired by Lewis Spence’s The Magic Arts In Celtic Britain, the words remain a mystery to Plant himself (“Maybe I was still trying to work out what I was talking about,” he told a press conference in 2012), but commentators believe that was the point. “They’re kind of universal,” says Salewicz. “They don’t quite make sense but anyone can interpret them as they want and project their own emotions into them. That’s one of the reasons for its popularity.”

Indeed, look past the quasi-pagan imagery of May queens, echoing forests and pied pipers and you might read a scathing attack on consumerism or, as Salewicz believes, a comment on “those gold-digger women that they would encounter everywhere… For an early lyrical essay it’s very sophisticated. It’s one of Plant’s first serious lyrical efforts.”

In many ways, “Stairway...” encapsulated its time. Led Zeppelin – and the wider prog firmament – had always been shrouded in a Tolkien-esque English folk-tale mythology, but it had never been so artfully crystalised. Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Pete Townshend had burnt, beaten and beatified their guitars in iconic rock-god fashion, but it was the image of Page wielding that double-necked guitar that came to epitomise the era of the classic guitar hero.

Meanwhile, acts such as The Beatles, The Who, King Crimson and The Beach Boys had been exploring multi-sectional techniques for some years in attempts to mirror the movements of classical music and earn rock the same high art respect, and the likes of Genesis, Deep Purple, ELO and Yes were actively trying to merge the two. But the gradual, seamless shifts of “Stairway…” made it multi-sectional not out of pretension, experiment or novelty, but in service of the song. It became the instant blueprint of what a mature, timeless rock track was supposed to be. “It set the whole mould for those American hard rock bands and their stretched-out anthems,” says Salewicz.

By refusing to release “Stairway…” as a single, Zeppelin forced their fans to buy Led Zeppelin IV to get their hands on the song, and the album subsequently flew. “The album almost sold as a single because of that,” Salewicz says, “but I don’t think it’s the only reason. It’s just one other element of Led Zeppelin IV because it’s such a powerful album.” Nonetheless, the song became the main set climax of Led Zeppelin shows for the rest of their career, stretching up to 15 minutes, but would become something of an albatross for Plant. When the band discussed returning to touring during their troubled final years, shortly before the death of drummer John Bonham in 1980 scuppered all future plans, Plant insisted that a “No Stairway” sign would be hung over future setlists. “There’s only so many times you can sing it and mean it,” he said. “It just became sanctimonious.”

“I don’t know what he associated it with,” Salewicz considers. “He blamed some of his family problems and the death of his son [Karac, who died aged five from a stomach illness while Zeppelin were on their 1977 US tour] on his immersion in the group and also he was concerned about Page’s dabbling with the dark arts. So I’m not sure if he saw the song as representative of a bad period in his life.”

Though “Stairway…” was one of just three songs the band played at their Live Aid reunion in 1985, Plant wouldn’t warm to the track in later years. “Lyrically, now, I can’t relate to it, because it was so long ago,” he told the Ultimate Classic Rock Nights radio show in 2019. “I tip my hat to it and I think there are parts of it that are incredible… it’s a very beautiful piece. But lyrically, now, and even vocally, I go, ‘I’m not sure about that.’” He once even pledged $10,000 (£7,000) to a Portland radio station asking for donations on the promise that they’d never play “Stairway…”, claiming that he liked the song, but he’d heard it before.

It also caused the band legal headaches. In 1982, it was cited as a prime example of backmasking by a Californian assemblyman trying to get warning labels placed on record containing backwards messages: when reversed, he claimed, the song’s middle section included lines such as “Here’s to my sweet Satan” and “There was a little tool shed where he made us suffer, sad Satan”. And Beelzebub-wielding Black & Decker was the least of their worries – last year they finally beat a seven-year plagiarism case from LA rockers Spirit, who claimed that Page had copied the opening arpeggios from their 1968 track “Taurus”.

Today, the song has weathered its periods of being overplayed, outmoded, decried and derided by punk generations. Fifty years on, “Stairway…” remains the prototype of so much big-league rock music without losing its power to thrill and bewitch. “It has allowed hard rock to win its spurs as a sophisticated musical style,” Guesdon argues, while Salewicz considers it “the archetype of classic rock now. It still sounds fresh. You don’t feel as though it’s past its sell-by date. It still really works.” Listen very hard, the piper’s still calling.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments