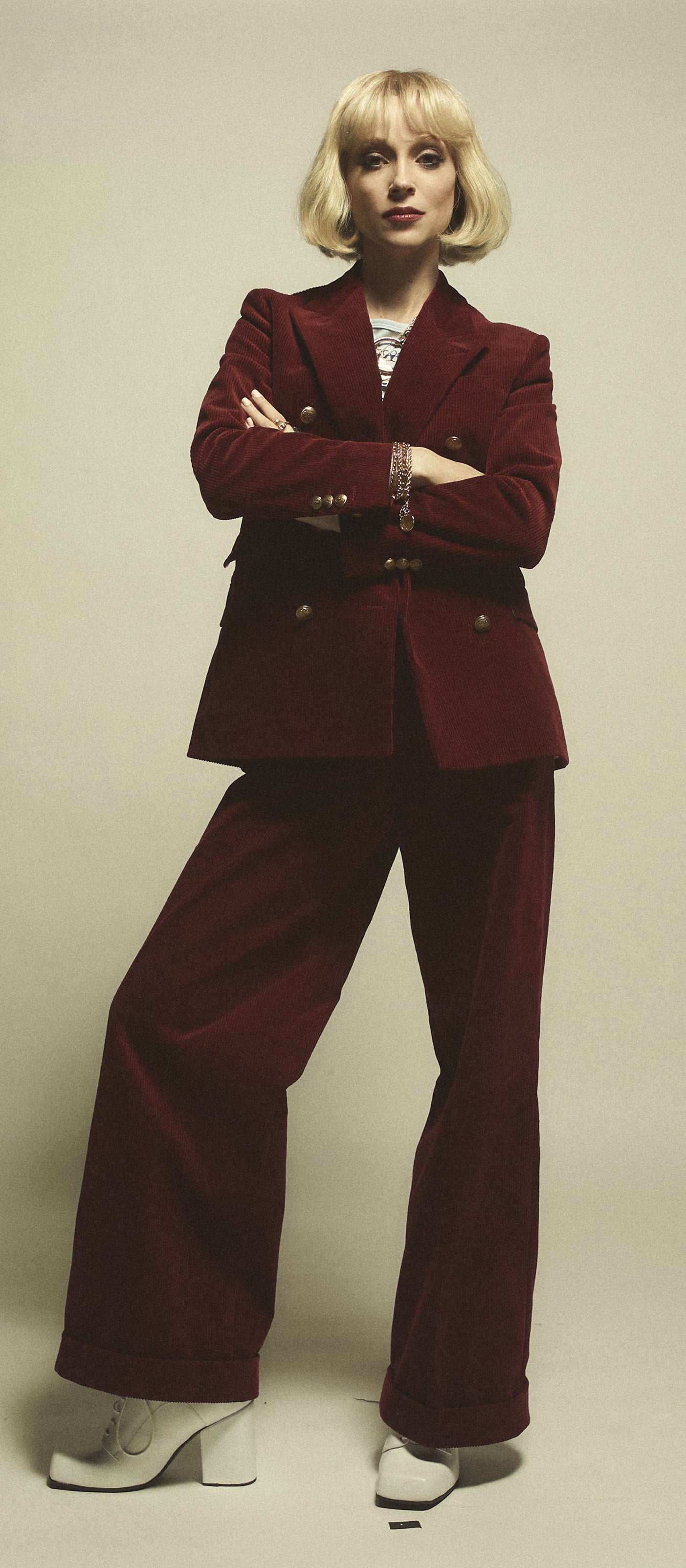

St Vincent: ‘At a certain point, we are all culpable. Just don’t be a s***ty person’

Annie Clark’s new album is her most personal yet. She talks to Alexandra Pollard about her father’s time in prison, the pitfalls of ironic detachment, and why society’s obsession with ‘making another one of you’ begs the question, ‘God, why are you so great?’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I’m good,” says St Vincent brightly. “I’m better than last time when I was a royal dick. So apologies for that, again.”

“Royal dick” is pushing it, but my last encounter with Annie Clark was definitely frosty. In 2017, off the back of no sleep, too many interviews and a clumsy comment on my part, the musician shut down on me. Her answers became either curt or disdainful; at the interview’s nadir, she pulled out her phone and told me to “keep asking away” as she typed. In the moment, knowing that Clark relished the odd power play – she had recently asked journalists to crawl into boxes with her and played pre-recorded answers if their questions were too mundane – I thought that she was toying with me. She wasn’t. I’d given her the impression that I hated the Masseduction tour she was still part way through – the decision to perform with just a guitar and backing track had already “incensed” some people – and she was genuinely upset. That cold indifference was a front.

The apology came a few days later. It was a sincere, warm one that gave explanations without making excuses. Clark told me how “horribly guilty” she’d been feeling. I should still write what transpired, she said, “but on a human level, f***, I’m really sorry”.

Today, Clark is like a different person. Even with her camera off, thousands of miles away in LA, the 38-year-old seems less distant than she did reclining on a chaise longue metres away from me, barely making eye contact. She is gentle, open, self-reflective – even a little nervous, often second-guessing how her answers are going to be received. (Her fears are proven right a few weeks later: she becomes Twitter’s pound of flesh for the day after a journalist self-publishes a slightly tense conversation with Clark, frustrated that the singer’s team had apparently asked for it not to run. Some wondered whether it was because the journalist had asked too many questions about Clark’s father’s imprisonment – but she seems perfectly happy to talk about that this evening.)

When Clark was growing up, her dad told her that the best way to lead her life was with “ironic detachment”. It was a good tip in theory, but emotions always break through that carapace eventually. “It’s so useful to be able to detach from the emotional, to go up and look at something from a bird’s eye view,” she says. “But the other side of ironic detachment is a lack of vulnerability, or an impenetrability, which is not actually helpful. It prevents communication and can be quite cowardly. But I do have to say, between my mother’s unwavering feminism and my dad’s insistence that all us girls be tough, I’m actually quite glad that there was a premium put on toughness. Sometimes you just have to be tough.”

But Clark is sensitive, too – more so than she necessarily lets on. The white-haired ice-queen from her self-titled masterpiece; the housewife on pills from Strange Mercy; the “dominatrix at the mental institution” from Masseduction, on which she tells me she was “performing femininity to the point where it was aggressive” – those were all characters. Or, at least, exaggerated fragments of Clark’s psyche. It is not as simple as St Vincent vs Annie Clark – they are both there, always, which can make things tricky when it comes to interviews. On stage, whether she’s throwing herself slow-motion down a flight of stairs or doing a jagged, carefully choreographed dance, she knows what she wants to present. But once she’s off-stage, at least in public, you get the sense that she is grappling with which self to be.

It is this juxtaposition that gives her music its affective alchemy. It finds a way to make the beautiful ugly, the ugly beautiful. Cold one moment, carnivalesque the next, it is swaggering and sentimental, formidable and vulnerable. Her sound was ambitious from the off – 2007’s Marry Me was a triumph of freewheeling art-rock, a xylophone here, a dulcimer there. With every album after that – Actor, Strange Mercy, St Vincent, Masseduction – her music grew increasingly riff-laden, those corrosive guitars offsetting her porcelain vocals like a chainsaw juddering beneath birdsong. The crunchier the guitars got, the more people clambered to work with her – Taylor Swift, Dua Lipa, David Byrne. The remaining members of Nirvana recruited her to front the band for their induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (she’ll be inducted herself one day, I’m sure). Clark has said a few times lately that to be described as “nice” would be the biggest insult to her; it is certainly not a word that ever applies to her music, even at its most raw and heart-wrenching.

Clark’s new album, Daddy’s Home, channels the sound of Seventies downtown New York. Thick with Coral sitars and prog guitars, it is both funkier and looser than anything she’s made before. “It’s very much like, ‘Welcome to this world, have a seat, have a drink’,” she says, “instead of aggressively, presentationally, ‘I’ll choke you until you like this’.”

Before I heard the album, I was sent a cartoon strip in the post. In the first panel was a drawing of Clark with tears running down her cheeks. In the reflection of her sunglasses, you could see a man being led away by two police officers. “I saw my pops taken away by the US government in May of 2010,” the cartoon strip read. “What followed were weeks and months of heartbreak, reckoning, drinking, punctuated, thankfully, by music.” Her father, a stockbroker, was sent to the Federal Correctional Institution in Seagoville, Texas, for “white-collar nonsense” – aka multimillion-dollar stock manipulation. He would stay there for a decade. The new album’s title refers to his release – although, as she puts it to me with a laugh, “it’s sort of a transformation too – I’m Daddy now”. Because it’s not a St Vincent record without a bit of camp.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

It’s nothing new for Clark’s music to be inspired by a deeply personal story. What’s new is how upfront she’s been about it. I suppose she felt lyrics like “I signed autographs in the visitation room/ Waiting for you the last time, inmate 502” might need some explanation.

“If I’m honest, I thought if I put it in the little comic strip, then I wouldn’t need to talk about it so much,” says Clark with a weak laugh. “I think I was really naive. It’s kind of hilarious how much I ended up talking about my own pops.”

For most of the past 10 years, she has barely talked about him at all. It’s obvious now that the trauma of her dad’s imprisonment is in the very bones of 2011’s Strange Mercy – with its references to “our father in exile for God only knows how many years” – but at the time, she kept shtum. And Clark’s fans, happy to just be dazzled by her, never demanded the cold hard facts. “To protect my family, I wasn’t keen on having it out in the world,” says Clark, who grew up in Texas after her parents split up. She has eight siblings, most of whom were still children when her dad went to prison.

Back when Strange Mercy came out, “I thought, ‘I’m not very established – the story would overshadow the work,’” Clark explains. Then in 2016, when she was in a relationship with supermodel Cara Delevingne and thus the subject of intense tabloid speculation, “the story was told without my consent”. In other words, the Daily Mail dug it up. By trawling through court records and doorstepping extended family members, the newspaper discovered and published intricate details of her father’s crimes – and just for good measure, threw in a claim that he’d failed to pay child support when he split up with Clark’s mother.

With Daddy’s Home, she decided to take back control of the narrative – or try to. “I wanted to be able to tell my version of it with humour and compassion and a lack of judgement,” she says. Where Strange Mercy felt like “a lifeline, some place to put it”, Daddy’s Home felt more celebratory. “Not to be Disneyfied about it, but he spent a decade of his life behind bars and he served his time and he’s out. It’s best-case scenario for the post-prison life – being integrated into the family and being a person among kids and grandkids and all that stuff. So there’s a sweetness to where it ended up.”

Still, Clark seems conflicted about how to talk about the situation beyond that. When I ask her how she feels about the US criminal justice system now that she has personal experience of it, she is torn – between wanting to use her platform to advocate for social justice, and not wanting to stake a claim in a struggle she has no place in.

“We’re still living the history of the enslavement of Black people in this country,” she says slowly, methodically. “There’s a direct line between slavery and incarceration. A direct line.” Drug laws designed to disproportionately affect Black and brown people, she says, are one of many “injustices that have been done to the descendants of formerly enslaved human beings. I have a lot of thoughts on the failings of the criminal justice system and the problems of monetising incarceration. So yes, it’s an American tragedy. It is.”

There’s a long pause. “So my own personal experience… it’s just one story. It’s not intended to encapsulate the entirety of the thing at all. The situation with my family, it’s not a result of the same lineage of slavery. It was a different thing. It’s my little sliver, which is that my father’s actions... the American criminal justice system said, ‘In exchange for what you’ve done, you’ll give us 10 years of your life. And then after that, you’ve paid your dues.’ And that was the exchange. And it’s wild to think about that. It’s wild to think about what people…” She breaks off. I hear a sharp, shaky intake of breath, and then a long sigh. “The prison system is American capitalism figuring out how to use humans as meat machines.”

Daddy’s Home is not just about Clark’s father’s imprisonment. On “My Baby Wants A Baby”, a swaying, Moogy feast with resplendent backing singers, she grapples with the prospect of motherhood. “I wanna play guitar all day/ Make all my meals in microwaves/ Only dress up if I get paid/ How can it be wrong?” she sings as the song builds to an almost frenzied climax. “What in the world, what in the world, would my baby say? ‘I got your eyes and your mistakes’.”

“If you’re an artist, you’re already married to your work,” says Clark, “and you don’t want to make any decision that’s going to make it so that you can’t make things. And for most people, their version of making things is procreation. Not that those things are mutually exclusive, but I think for the female artist, it’s just an extra layer of, ‘What do you do?’ There’s this bare, neurotic voice of ambition [on the song]. And the dirt-bagginess. I’m definitely being self-deprecating but it’s not that far off. If left to my own devices, I would barely survive in a conventional way. So the song’s just exploring all of that. How much weight society puts on [the idea] that truly the best thing you could do is to make another one of you. But God, why are you so great?”

Both art and babies, I suggest, are ways of making yourself immortal. Is Clark’s legacy something that fuels her? “I don’t actually think about it. I have a very good ability to focus on what’s in front of me. I have a hard time imagining that far into the future, but I don’t look back. I’m just sort of in whatever I’m in.” That’s quite a rare talent – the ability to just be present. “Well, make no mistake, I worry about the present.”

I hope I’m making it easier for the next generation

On “The Melting of the Sun”, a sultry jam with one of the album’s best refrains, Clark does look back – to women like Joni Mitchell and Tori Amos who she feels paved the way for her. “I feel like I’ve benefited from their bravery and I wanted to say thank you,” she explains, “and to say, ‘You made it easier for me, and God I hope I’m making it easier for the next generation.’” Then again, she adds, “I didn’t walk around feeling a lot of hostility coming up in the industry. I didn’t have an antenna that was tuned to that station. I wasn’t in every room – I’m sure there were plenty of objectionable things that were done – but if I ever encountered sexism to my face, I would kind of make it their problem.” Does she think that’s because of the way she was brought up? “I do. I mean my mother’s motto for us was, ‘We girls can do anything’. To the tune of the Barbie song, by the way. So when I encountered it, it either confused me or I would make it their problem. I would say something snide, leave them holding the bag of their own shame. ‘No, don’t put this on me, that’s for you.’”

Zoom warns me that the meeting’s about to end, so I wonder aloud if we should hang up now and reconnect – but Clark isn’t listening. “I mean, this is such a hairy world to get into. I probably shouldn’t have said anything.” About what? “Well, just about sexism. I’ll get accused of victim-blaming and that’s not it at all. I’m just… yeah.”

The call cuts out. When we reconnect, I ask instead about “Down”, on which she sings so close to the microphone, it feels like a threat. It’s a song with no time for excuses. “Tell me who hurt you – no wait I don’t care/ To hear an excuse why you think you can be cruel.” “I’ll never say who it’s about,” Clark tells me with a chuckle, “but yeah, it’s a revenge fantasy. At a certain point, we are all culpable. Just don’t be a d***. Don’t be a s**tty person. There’s not even that much more I can say about it.”

It reminds me of the many famous men who’ve responded to accusations of abuse or misconduct by referring to their own personal demons. Was that on her mind? “Probably ambiently so,” she says. “The song was not in reference to that specifically. We are in an interesting time of trying to figure out the tantamount consequence for action. And if it can’t be legislated in a court of law, people are going, ‘What is it this person deserves for this transgression?’ And we haven’t figured out any clean lines for that yet. It’s a wild time. It’s the wild, wild west.”

That’s when terms like “cancel culture” get thrown around, I say. “Yeah, and unfortunately the right co-opted the term ‘cancel culture’ and used it in ways that were intentionally misleading. And so now, if you want to have a thoughtful conversation about action and consequence, you can sound like a pundit on the right decrying cancel culture. Unfortunately, the right is very good at packaging things and serving neat lines of outrage. But we have to be careful of lack of nuance, everywhere. That’s dangerous.”

As for Daddy’s Home, it is a record about “flawed people doing their best to survive”. “This record is from guts and pelvis,” says Clark. “All I really want to do is just make the best work I can. I kind of don’t give a f*** about anything else. It’s a real like, ‘Take it or leave it, like it or don’t, either way is actually fine for me because I love it.’” She laughs. “It’s a good place to be, not giving a f***.”

Daddy’s Home is out on 14 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments