Nothing compares to it: Revisiting the wild story of Sinéad O’Connor’s hit 35 years on

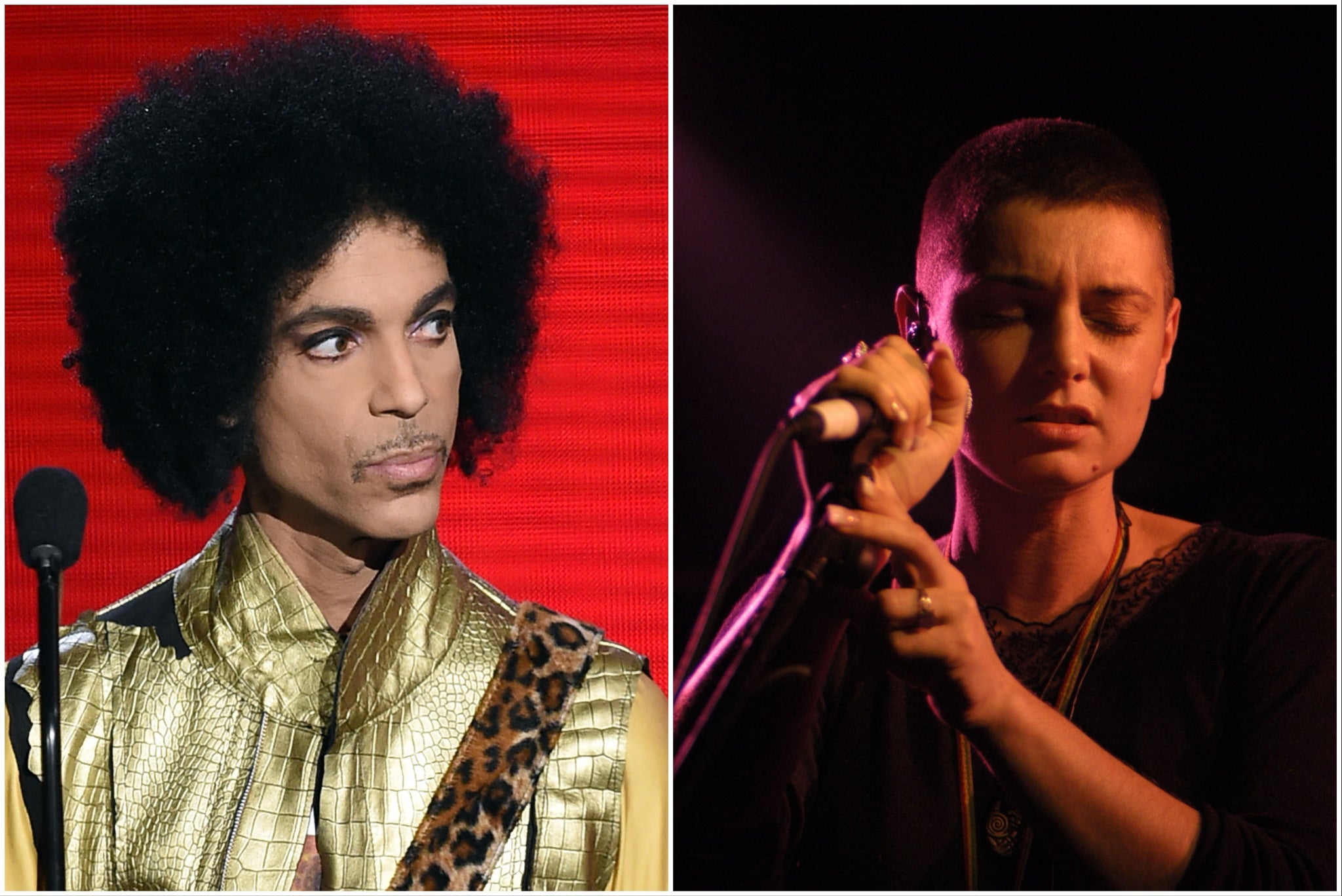

Everyone remembers the Irish singer’s mesmerising video for ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’. Few know that Prince was the musician who wrote and released the original – or the level of chaos that ensued when he and O’Connor met. On the song’s 35th anniversary, Mark Beaumont delves into its emotive story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When a long black limo pulled up outside Sinéad O’Connor’s LA home one night in 1990, she imagined it was her Cinderella moment. A grand carriage, dispatched to whisk her to her Prince. When she told friends that The Purple One had called earlier that night to suggest a meeting, and then sent a car to pick her up, they got romantic ideas. “We all thought maybe me and him would fall in love,” O’Connor wrote in her 2021 memoir Rememberings. Or that at least they’d get along. “We thought ‘He must be wanting to celebrate the song doing so well. There’ll be cake!’”

“The song” had done very well indeed. O’Connor’s lustrous, synthetically orchestrated version of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U”, released on 8 January 1990 – 35 years ago this week – had broken the world’s heart with just two tears on a young woman’s cheeks.

Those tears were shed by O’Connor in John Maybury’s starkly emotional video for the song, as the singer thought about the mother she’d lost in a car crash four years earlier. “I didn’t know I was going to cry when I sang in the video because I didn’t cry in the studio recording it,” she said later; she revealed in Rememberings that she always thought of her mother when performing the song. “I feel it’s the only time I get to spend with my mother and that I’m talking with her again. There’s a belief that she’s there, that she can hear me and I can connect to her.”

The raw journey O’Connor took through the song – grief, anger and pure desolation, as the track’s deft poetry demanded – animated and encapsulated the loss and heartbreak of millions. It reached No 1 in 14 countries, including the UK and the US, and sold 3.5 million copies in 1990 alone. Today it stands as one of the defining tracks of the 1990s and one of the most moving and beloved cover versions ever recorded.

Surely, at Prince’s house, there’d be cake? Instead, O’Connor slid into the back seat of the limo to be driven to one of the most acrimonious celebrity meetings in pop history. “We had a punch-up,” she told Norwegian radio station NRK in 2014. “He summoned me to his house, and – it’s foolish to do this to an Irish woman – he said he didn’t like me saying bad words in interviews. So I told him to f*** off. He got quite violent. I had to escape out of his house at five in the morning. He packed a bigger punch than mine.”

It marked an ugly end to one of pop’s most beautiful stories. Prince first wrote the song in July 1984, during a prolific period in which he wrote and recorded a song each day. Fresh from a flight from Dallas, where he’d been to watch the Jacksons’ Victory tour, he returned to the Flying Cloud Drive Warehouse, just outside Minneapolis, where he was working on the one and only album to come out of his funk side-project The Family.

According to his engineer Susan Rogers, the song flooded out of him in an hour. “I was amazed at how beautiful it was,” she said in Duane Tudahl’s book Prince and the Purple Rain Era Studio Sessions. “He took his notebook and he went off to the bedroom, wrote the lyrics very quickly, came back out and sang it. I was very impressed with it.”

Prince’s own inspiration for the song has been the subject of much debate. In his memoir The Beautiful Ones, published three years after his death, he wrote about his mother making “late night calls and pleas” to his father after their separation, and of being enlisted to beg his dad to return to the family. “I think that’s why I can write such good breakup songs, like ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’,” he wrote. “I ain’t heard no breakup song like I can write... I have that knowledge.”

Some imagined that Prince had drawn insight from his relationship with The Family’s Susannah Melvoin, one of the song’s two original singers. However, Jerome Benton, another member of The Family, believed that the song was based on the heartbreak he had shared with Prince over the collapse of his own engagement.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Rogers argued that lines such as “All the flowers that you planted, Mama, in the backyard/ All died when you went away” were directed at Prince’s former housekeeper Sandy Scipioni, who had recently left Prince’s employment after her father suffered a heart attack. “It would have been Sandy who planted those flowers,” Rogers told The Guardian in 2018. “Sandy ran Prince’s life. He kept asking, ‘When’s Sandy coming back?’”

Alongside all this pain, at least one story connected to the song had a happy ending. In order to summon the required emotion for the song, The Family’s other singer Paul Peterson recalled memories of being heartbroken by a girl called Julie in high school. A few years after the release of the track, Julie and Paul were married.

As the song topped charts worldwide and propelled ‘I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got’ towards 7 million sales and four Grammy nominations, it seemed as though the world wept along. All except Prince

The Family’s heavy-handed rendition of the song swiftly sank into obscurity – until O’Connor’s manager and then-partner Fachtna Ó Ceallaigh remembered it at a point when his relationship with O’Connor was falling apart. Ó Ceallaigh wisely suggested that O’Connor cover the track on her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got.

Since she’d made her name with the impassioned, confrontational pop-rock of her 1987 debut The Lion and the Cobra, this was a chance for O’Connor to showcase a more delicate side. Between engineer Chris Birkett, his co-producer Nellee Hooper (of Soul II Soul fame) and Japanese jazz virtuoso Gota Yashiki, a minimalist synthesised orchestra and drum-loop backing was crafted, uncluttered by bass, against which O’Connor’s vocals could swoop and rage. “It’s a bit like the Stanislavsky acting method,” she later told the BBC. “You have to find emotional stuff inside yourself that you can use.”

Yashiki remembers the sessions as being as smooth as the song. “The atmosphere was calm, relaxed, yet serious and focused,” he says. “There was no shouting or arguing, and very little laughter.” It was O’Connor, he says, who drew the core of the song from Prince’s original. “Sinéad suggested simplifying the chord progression as much as possible because the original was quite complex.”

According to Birkett, the recording took just over a day to complete. He recalls O’Connor’s vocal take as a moment of instant sonic alchemy. “She nailed it in one take,” he says, “then she said ‘I wanna do a double track’ and sang the perfect double track. It sounds like one voice, it’s so tight.”

O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” very nearly followed the fate of the original. A few weeks after its release, the song was brushing the underside of the Top 40 when the BBC decided to drop it from its playlists. It was Maybury’s video, swiftly filmed in Paris, that made the track a global heartbreaker. “She did a great performance, crying real tears in the video,” he says, “and that video is the thing that really broke it. Suddenly the sales picked up and it was No 1. Without that video, it would probably have disappeared.”

As the song topped charts worldwide and propelled I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got towards 7 million sales and four Grammy nominations (it won the award for Best Original Music Performance, though O’Connor refused to accept it), it seemed as though the world wept along. All except Prince. As that long black limo delivered O’Connor to the front door of Prince’s sprawling mansion in the Hollywood Hills, she was met not with cake but with confrontation.

Her description of the evening, according to Rememberings, would have made a great horror-film script. After being led through reception rooms with vast windows covered with aluminium foil (“He don’t like light,” a nervous underling informed her) to a small kitchen, she was first challenged by Prince for her foul language in interviews, then invited to have a pillow fight with her host. “On the first thump I get,” she wrote, “I realise he’s got something in the pillow, stuffed down the end, designed to hurt.”

O’Connor managed to escape the house at 5am and hide in the gardens while he searched for her. She then made her way to a highway, where he tracked her down and chased her, hurling violent threats. It was only by ringing the doorbell of a nearby house, O’Connor claimed, that she eventually scared him away.

In subsequent interviews, O’Connor expressed the belief that she may have become unwittingly embroiled in a business wrangle between Prince and her manager Steve Fargnoli, who had previously managed Prince. She also suggested that the singer had been angered by the fact that she’d covered his song without being offered it, circumventing his usual process. “He was uncomfortable that I wasn’t a protégé of his,” O’Connor said.

O’Connor’s description of the secretive Prince as a threatening, demanding and controlling presence has seen bad blood linger. Prince’s estate refused permission for director Kathryn Ferguson to use the song in her 2022 documentary about O’Connor’s life, Nothing Compares. “I didn’t feel [O’Connor] deserved to use the song my brother wrote in her documentary so we declined,” Prince’s half-sister Sharon Nelson said in a statement. “His version [released in 1993] is the best.”

Prince’s version gained traction in the US, particularly after the furore over O’Connor ripping up a picture of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live in 1992. “Sales in America went down to literally zero the week after,” Birkett says. “It was selling millions of copies and then nothing. That one act cost me about a million dollars in royalties.”

Yet the song has become inextricably entwined with both artists’ lives and deaths. The week after O’Connor died in 2023, the track re-entered the UK chart, while on Prince’s death in 2016, radio stations across the US conspired to play his version of the song exactly seven hours and 13 days – in accordance with his original lyrics – after his passing.

The track itself has proved immortal. “The lyrics resonate with people all over the world,” says Yashiki. “The simple line ‘Nothing compares to you’ allows listeners to project it onto someone special in their own lives.” It remains, in tear-jerking terms, incomparable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments