Freedom, festivity and dead by sunrise: Inside Sid Vicious’s drug-fuelled last party

Less than 24 hours after Sid Vicious left Rikers prison after breaching his bail on charges of murder, he was found dead at the home of an aspiring actor. Mark Beaumont speaks to his long-time friends and experts about what happened that fateful night – and everything that led up to it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

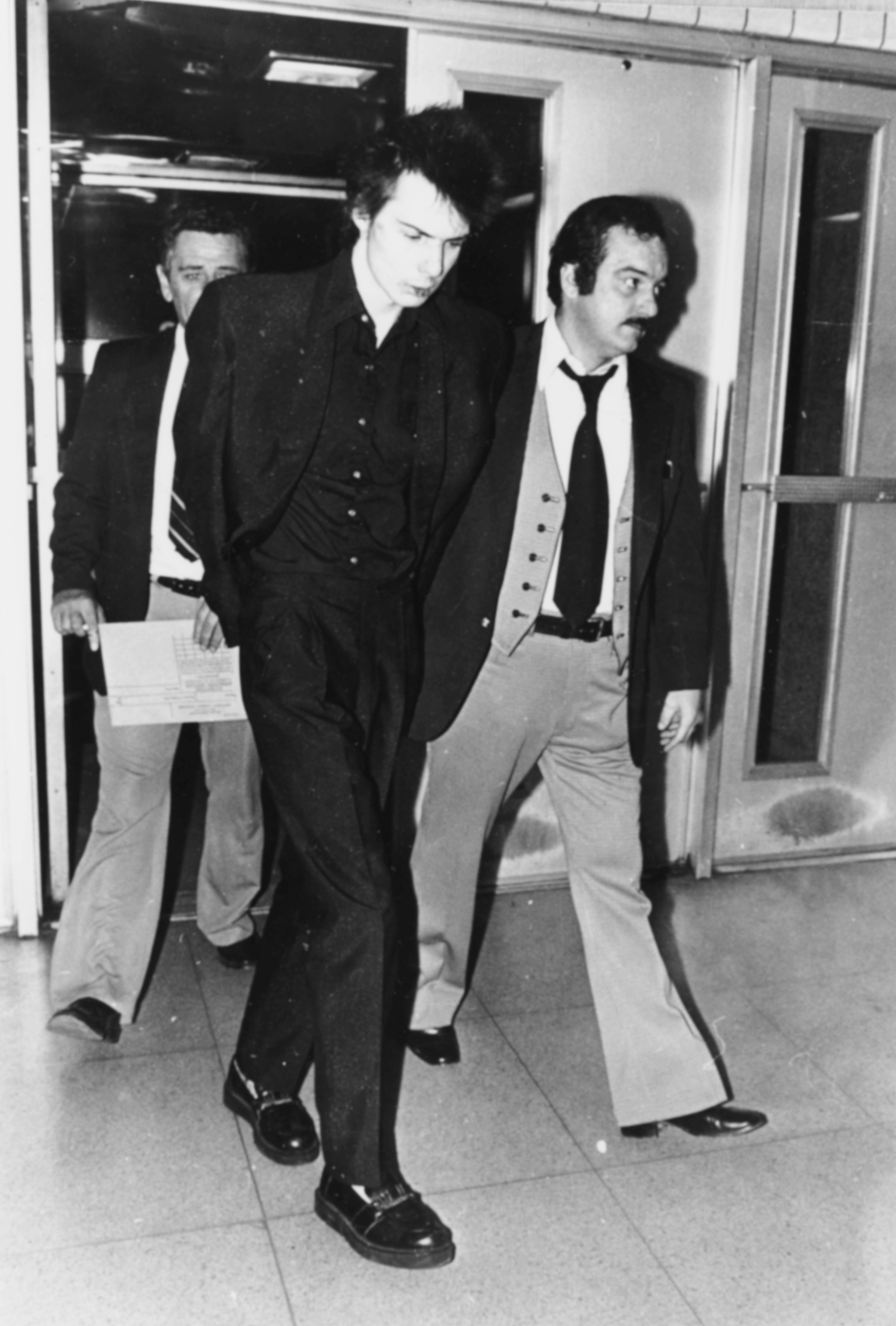

Your support makes all the difference.When Sid Vicious stepped out of Rikers Island, New York, on 1 February 1979, oblivion was the first thing on his mind. During the 54 days he spent in the notorious Bronx prison – there for breaching the conditions of his $50,000 bail from charges of murdering his girlfriend Nancy Spungen three months earlier – he’d undergone enforced cold turkey to rid him of the heroin habit that had blighted his days as Sex Pistols’ second bassist and punk’s definitive wildman. Staying clean, though, was never going to be part of the Vicious script.

Having made his way to Manhattan, Vicious ran into a photographer friend and drug buddy Peter Gravelle. Vicious – born Simon John Ritchie – asked Gravelle to bring $200 worth of heroin to a small gathering taking place that night to celebrate his release. The address was Bank Street, at the apartment of aspiring actor Michelle Robinson, one of several women Vicious had been seeing since Spungen’s death – for which he’d never stand trial because by tomorrow morning, 45 years ago, Vicious, too, would be dead aged just 21.

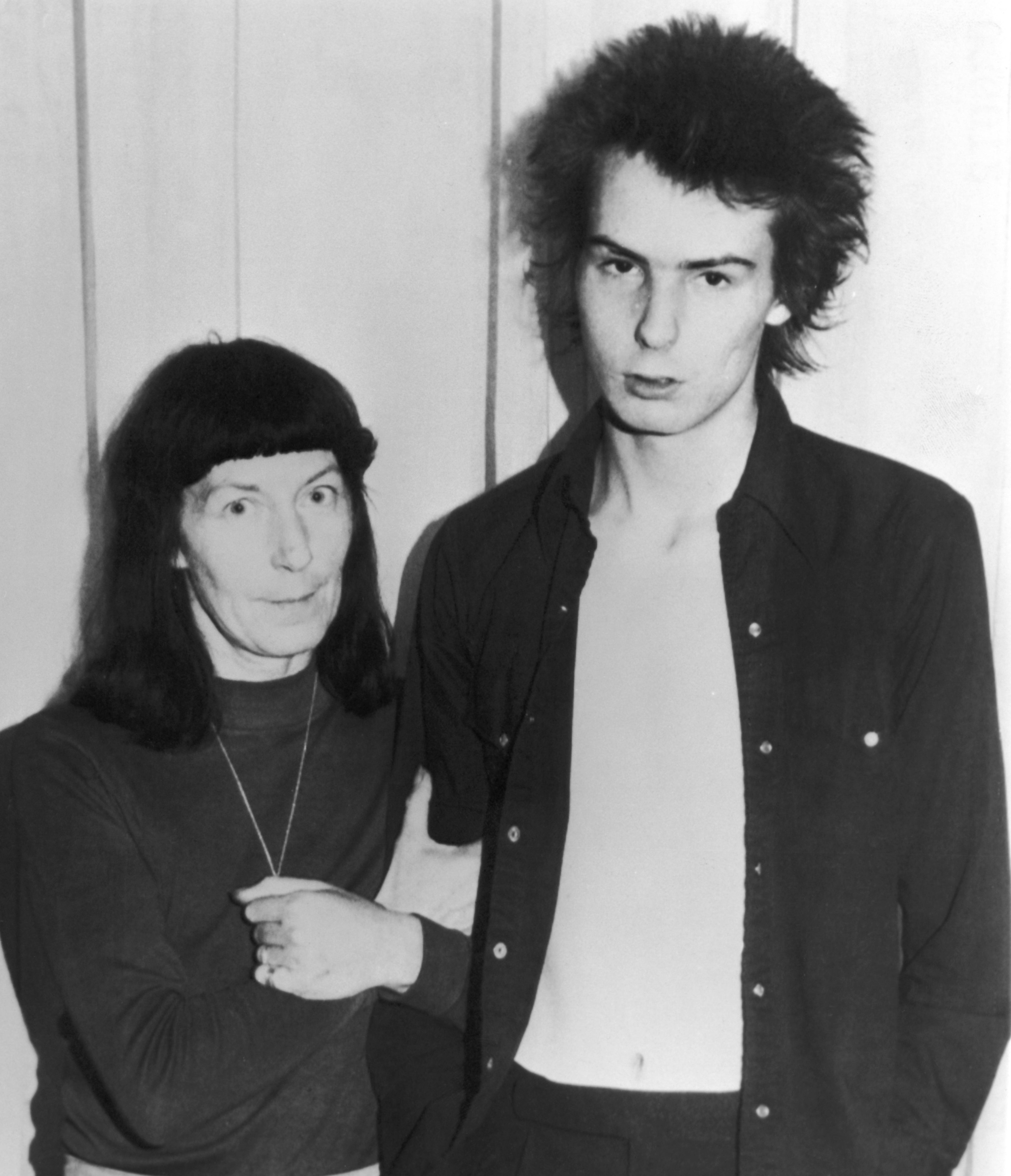

In the months that followed his death, much evidence would be presented to suggest that Vicious was of a self-destructive mindset that night. His mother Anne Beverley, herself a long-term heroin addict, produced a hand-written letter she claimed to have found in his leather jacket, referring to Spungen. It read: “We had a death pact, and I have to keep my half of the bargain. Please bury me next to my baby. Bury me in my leather jacket, jeans, and motorcycle boots. Goodbye.”

Spungen’s mother, Deborah, claimed to have received a similar letter from him, in which he agonised over how he hadn’t died with Nancy that fateful morning of 12 October 1978 at the Chelsea Hotel, where Spungen was found dead from a knife wound. “I promised my baby that I would kill myself if anything ever happened to her and she promised me the same,” Vicious wrote. “This is my final commitment to my love.” In the weeks following Spungen’s death, back in the Chelsea Hotel on bail, he’d been admitted to hospital for slashing his arms with a smashed light bulb. During one of his final interviews, when asked where he wanted to be, Vicious replied “under the ground”.

Yet when Gravelle arrived at 63 Bank Street that night, joining Vicious, Robinson, Beverley and five other close friends, he found Vicious in a defiant, future-facing mood. “The last feeling I got from them was sort of positive,” Gravelle tells me now. “He basically talked about how he was going to get himself off the [murder] charge and go upstate New York to record this album, which was gonna pay for all his legal fees and everything. On the list of songs was ‘I Fought the Law’, which The Clash did later on and I remember ‘YMCA’ was on there too. He was into that.”

Misfits’ Jerry Only and The Blessed’s Howie Pyro were among the friends who left before the drug-taking began, but Gravelle stayed and witnessed first-hand how the narcotics wreaked havoc on Vicious’s recently detoxed system. “He took a bunch of heroin and he started to turn blue,” he recalls. “We brought him round and I stayed with him for about another three or four hours, until about two in the morning or even later. When I left, he was fine. He was up, he was drinking tea, a bit weak and everything but he was okay. He hadn’t died from that hit of heroin, put it that way.” The next day, Gravelle received a call from a friend imparting the news: “I went out and it was already in the evening newspapers: ‘Sid Vicious Dead’, I couldn’t believe it.”

Others were less surprised. “Once you’ve got a heroin habit, where do you think that goes?” asks long-time friend John Wardle, aka Jah Wobble, who made the 2009 Radio 4 documentary In Search of Sid, and whose days in the formative punk scene are recalled in his forthcoming expanded autobiography Dark Luminosity: Memoirs of a Geezer. “When you take drugs and booze too much, you enter a hell-world.”

Rat Scabies of The Damned, whose first gig was in support of the Sex Pistols, sees Sid’s death in an equally fatalistic light. “If you’d invented the Sid Vicious story as a cartoon or a novel, it ticks every box,” he says. “In a funny way, it was the only ending he could have had.”

That Vicious succumbed to a drug overdose at such a young age cemented his place in the pantheon of tragic rock’n’roll figures straddling – lip forever curled – the dark divide between icon and victim. But if there was an inevitability to Sid’s fate, it was rooted in his upbringing. “I don’t think Sid had a proper foundation in his life,” says Jon Savage, author of 1991 punk bible England’s Dreaming. “I met [his mother] Anne Beverley and I liked her, but I didn’t think he had proper parenting.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Wobble agrees. “Single-parent family, mum’s addicted, it’s not going to end well,” he says. He first met Vicious at London’s Kingsway College of Further Education around 1974. They were two troubled teens enthralled by the snarling charisma of fellow student John Lydon.

Having spent his youth moving between Tunbridge Wells, Bristol, the high-rises of Stoke Newington, and the hippie enclaves of 1970s Ibiza – where Anne, abandoned by Sid’s guardsman father, reportedly sold dope to survive – Vicious landed in Lydon and Wobble’s orbit unguided and adrift from a drug-addicted mother who didn’t even know what school he was attending. Perfectly primed, then, to epitomise the punk scene forming around the duo.

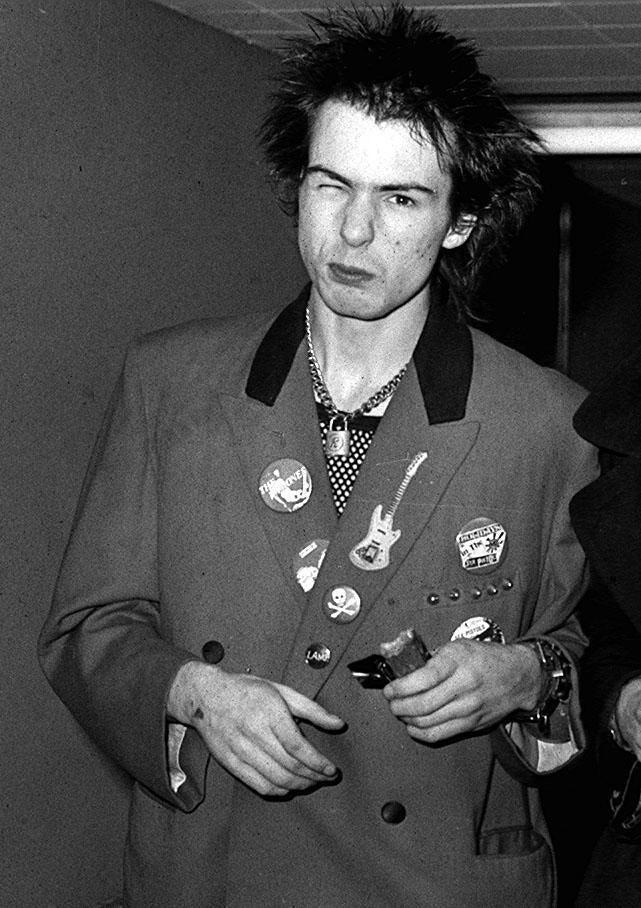

Indeed, when Malcolm McLaren sniffed out Lydon to audition as Sex Pistols singer from among the gutter chic mongrels hanging around his and Vivienne Westwood’s Sex boutique, he went out looking for the wrong John. It wasn’t Lydon, but Vicious, then going by John Beverley, who Westwood had recommended for his perfect “Blank Generation” style of spiked black hair, leather jacket, twig-like frame, and permanent, life-engendered sneer.

Despite not landing the Pistols gig, Vicious fully embraced the band’s aesthetic: its nihilism, anger, and anarchy. “He epitomised the postmodern age,” Wobble says. “That was the mantra: everything’s s***, everything’s been done. He was somebody who really lived the ideals of punk, insofar as being very extreme, very nihilistic, very self-destructive, completely not giving a f*** for social convention or bourgeois values.”

For Vicious, inventor of the pogo dance, that rebellious energy bled easily into violence. Pumped with amphetamines (Wobble witnessed him mainlining the drug from his late teens), Vicious threw a pint glass against a pillar during a Damned gig at the 100 Club, blinding a woman in one eye. He also took a bike chain to the head of NME’s Nick Kent at a Sex Pistols show at the same venue. Vicious would burn himself with cigarettes and cut his arms with the lids of baked bean tins for attention. Wobble remembers him once stabbing a Bethnal Green flatmate with a meat fork during an altercation at a house party and killing a cat by throwing it out the window of a Hampstead squat.

He had that thing of looking for weakness in people that characterises cruel teenagers, and in a way, he was the eternal teenager

Wobble is wary of Vicious being painted as a poster boy of thuggish punk attitude, though. He variously describes his late friend as vulnerable, brave, and witty, albeit with a mean streak. “He could be quite snidey,” Wobble says. “He had that thing of looking for weakness in people that characterises cruel teenagers, and in a way, he was the eternal teenager. I think he was terrified at the thought of growing up. There was obviously a lot of anger in him. Any psychiatrist could go to town on him.”

One tried. Wobble was asked to accompany a 17-year-old Vicious to sessions with a psychotherapist after he had expressed suicidal intentions. “We turned it all into a joke,” he says. They concocted a ploy to sabotage the session; when the psychiatrist asked Wobble to help convince Vicious life was worth living, Wobble informed his pal that he was friendless, pointless, and better off dead. “Sid looked at the psychotherapist with an expression of, ‘See, I told ya, no one likes me, life’s worthless, no interest.’ He was astounded, this bloke,” says Wobble. “He ushered us out in the end, and we walked up the road, got out of sight and burst out laughing – but I’ve come to realise many a true word’s spoken in jest.”

Following brief stints in Flowers of Romance and Siouxsie and the Banshees, Vicious was hired to replace Glen Matlock as Sex Pistols bassist in February 1977. He was exactly the definitive punk poster boy McLaren wanted at the heart of the group. “When Sid joined, he couldn’t play guitar, but his craziness fitted the structure of the band,” McLaren said later. High on pop stardom and heroin, Vicious threw himself wholeheartedly into the role.

Sid’s musical contributions were virtually non-existent. His bass parts on the Pistols seminal debut Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols were largely played by Steve Jones, and his on-stage impact was primarily ideological. On the band’s final tour in America in 1978, Vicious abused the local cowboys in Southern bars to a Blues Brothers-esque reception. He hit hecklers with his bass and slashed the words “gimme a fix” into his chest, intent on making sure America didn’t feel cheated by punk. During one truck stop meal en route to the final show in San Francisco, he responded to a group of rednecks mocking his aggressive look by stabbing himself in the hand with a steak knife, mid-mouthful.

The problem was, punk was a creative cultural explosion – one that wouldn’t survive being reduced to such a yob rock archetype. “Sid was a kind of cartoon and the Sex Pistols kind of became a cartoon really quickly,” says Savage “That’s why they couldn’t carry on.”

He represented for me that nihilistic, self-destructive, dark, completely uncaring side of punk –but he dulled. He was with Nancy, he was really into smack, he was cutting himself, it was all pretty sad and uninteresting

At the tour’s end, Lydon quit the disintegrating band and Vicious almost quit breathing. On a flight from San Francisco to New York City, he slipped into a coma induced by methadone, diazepam, and alcohol. On coming round, he was given six months to live unless he quit drinking.

“He represented for me that nihilistic, self-destructive, dark, completely uncaring side of punk,” says Wobble. “But he dulled. He was with Nancy, he was really into smack, he was cutting himself, it was all pretty sad and uninteresting.” Punk’s anti-bourgeois attitude meant there was no support at hand for a self-destructive addict thrown to the wolves of money and infamy. “It was really square to show responsibility,” says Wobble. “So nobody was going to put an arm round Sid and guide him. It would’ve been very difficult anyway; he’d have probably sneered at that.”

Yet music still offered him a lifeline. With McLaren trying to salvage what he could of the Pistols’ momentum, Vicious was called on to take over vocal duties for several songs in the mockumentary The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle, eventually released in 1980. The Pistols scored some of their biggest UK chart hits with Vicious’ acerbic, confrontational, and foul-mouthed covers of “My Way” and Eddie Cochran’s “Somethin’ Else”. Meanwhile, he and Matlock buried the hatchet to form the short-lived post-Pistols supergroup Vicious White Kids.

“He was broke so he wasn’t in a great place,” says Scabies, who played drums at the band’s first and last show, at Camden’s Electric Ballroom in August 1978. “But at the same time, he almost had the world at his feet. He wasn’t always on time for rehearsals, but he’d turn up and he knew the song.” Lacking any original material or much musical ability, Vicious got by on persona value alone. “What he was really good at was knowing what he was,” Scabies argues. “You go back to Robert Plant and people like that, they weren’t traditionally regarded as great vocalists, but they knew what they were and what they could do with it. Sid’s real talent was that he was very aware of who Sid Vicious was.” And Camden’s punk diehards lapped him up; with only 25 minutes of material rehearsed, the band had to play the set twice.

With Spungen as his self-appointed manager, Vicious then flew to the US to put together his own band for a series of similarly raucous, money-spinning punk and garage rock cover shows the following month, many at legendary New York punk haunt, Max’s Kansas City.

“I thought they were horrible,” says Gravelle of the shows immortalised on 1979’s posthumous live album Sid Sings, complete with between-song catcalls and crowd abuse. “They packed the place out with people, it was so hot and sweaty in there and the sound was abysmal. It could have been anybody up there.” But the money was good. “I think they’d probably walk away with $14,000 or $15,000 per night, which wasn’t bad,” says Gravelle. “But of course, it all just went on drugs – in one door and out the next.”

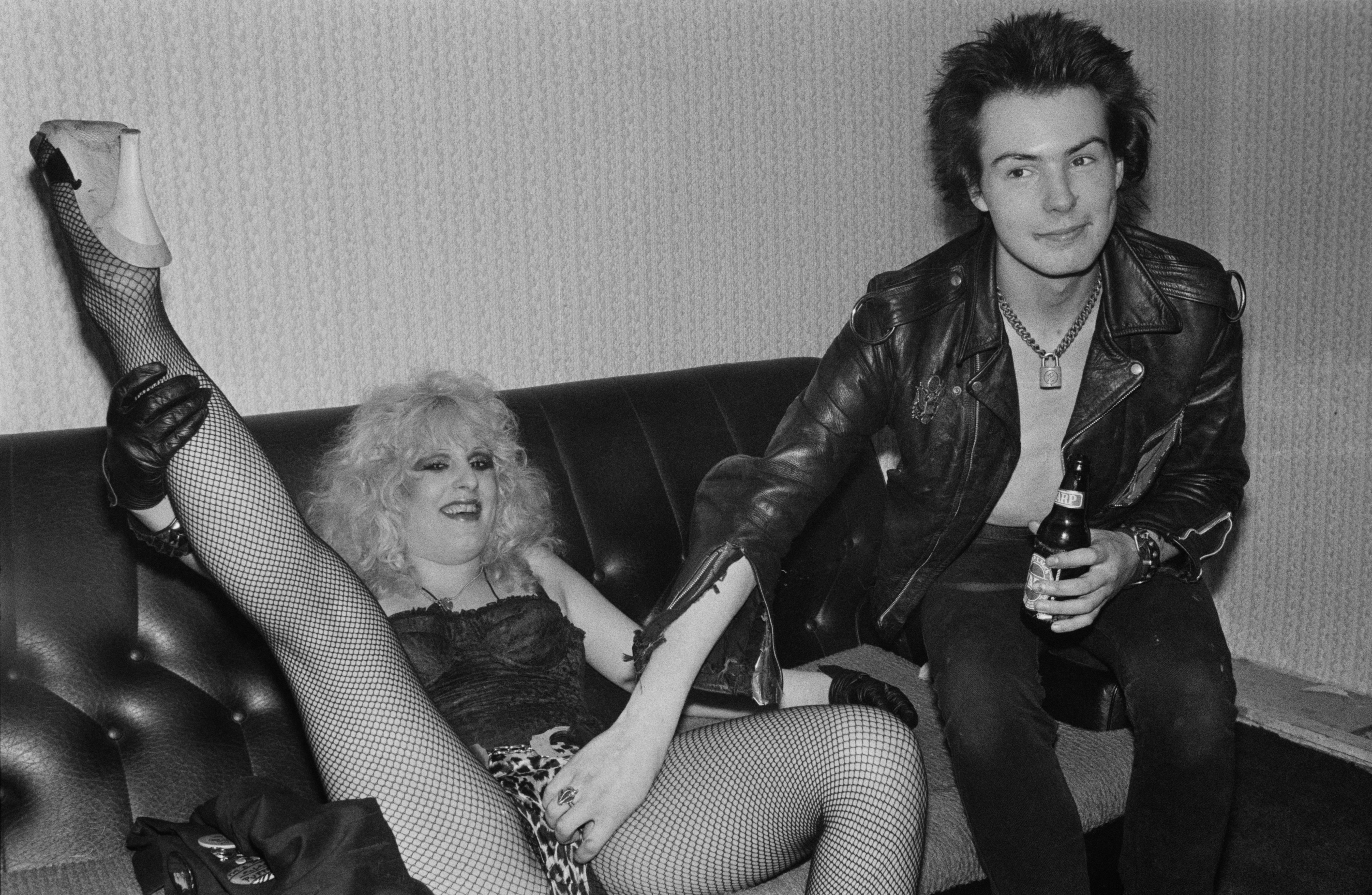

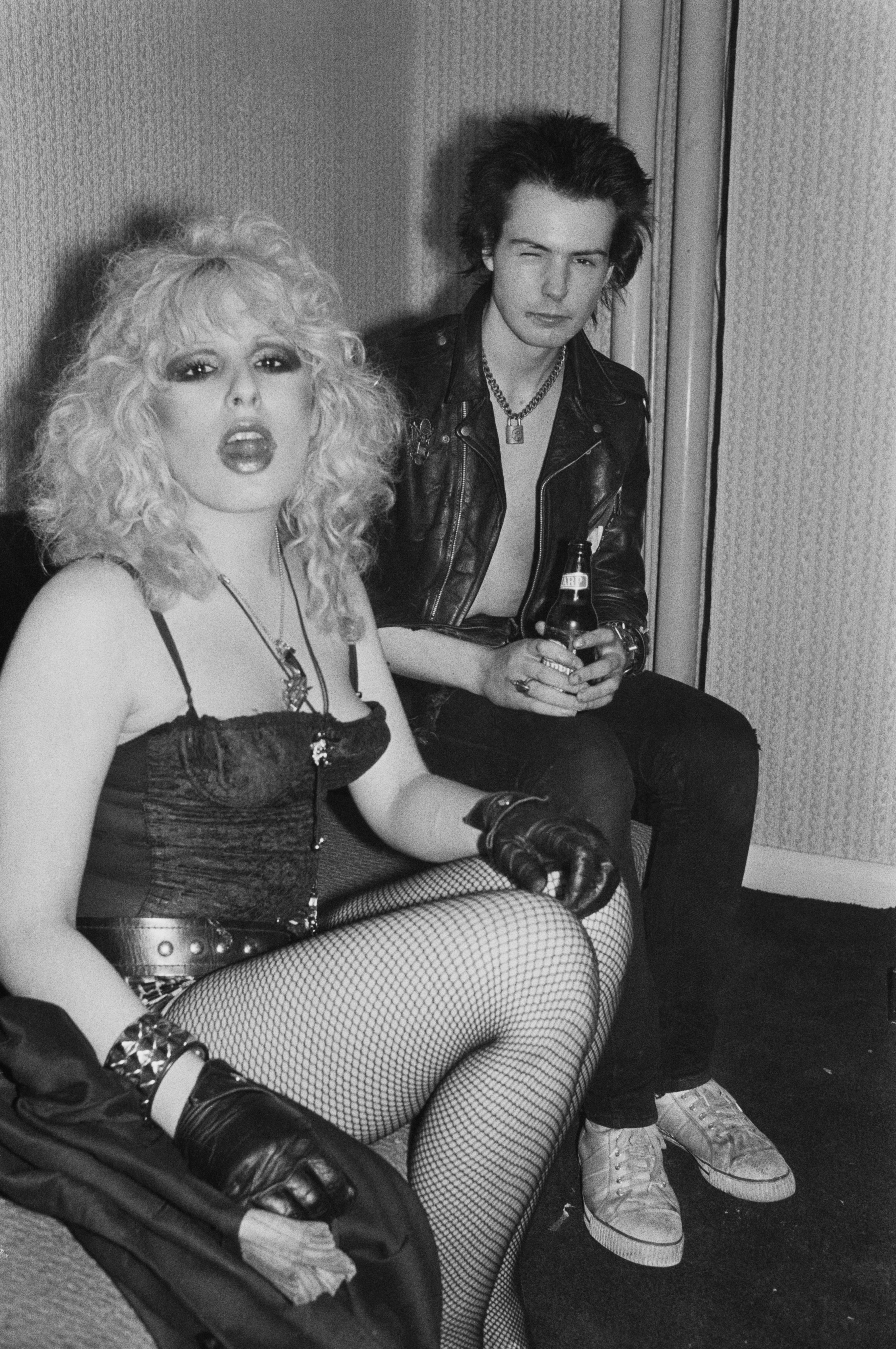

Vicious first met the Pennsylvania-born Spungen in March 1977. She was a blonde, brash, and schizophrenic 19-year-old given to self-harm, drug abuse and occasional sex work. The couple’s love affair with heroin was as intense as their romance. Visitors to their New York bolthole in Room 100 of the Chelsea Hotel often found them in a nest of trash and bedsheets, wasted, and engrossed in cartoons.

Whether nature or narcotic, their relationship fluctuated wildly between adoration and abuse. Vicious worshipped Spungen, but he also beat her. Once, he claimed to have watched her give oral sex to a stranger in an alleyway for £15. Media notoriety only fuelled their need to live up to their own legend. “The press portrayed Sid and Nancy as Romeo and Juliet in black leather, roaring into hell,” said Spungen’s mother.

The pair crashed through Hades’ gates on the night of 11 October 1978. Following an open-door party in their Chelsea Hotel room, Spungen, aged 20, was found dead in the bathroom from a stab wound to the abdomen seemingly inflicted by a Jaguar K-11 knife she’d bought for Vicious just the day before.

Speculation swirled. McLaren pushed the idea that another Chelsea Hotel junkie might have killed her for the money, himself cashing in by releasing a T-shirt featuring Vicious framed by a bouquet of blood-red flowers and the words: “SHE’S DEAD. I’M ALIVE. I’M YOURS.” Suspicions also fell on various dealers who were in attendance, including actor and stand-up comedian Rockets Redglare. Under arrest, Vicious both denied and admitted to Spungen’s murder: “I stabbed her, but I never meant to kill her,” he told police. He would later retract his confession. Having taken 30 Tuinal pills and drunk a bottle of Jack Daniels that night, he was understandably confused.

“I asked him after he got out from Rikers, I said, ‘What happened? Did you kill Nancy?’ and he couldn’t remember,’” says Gravelle. Having published several essays on the “botched job” of the police investigation and the possible scenarios of Spungen’s death, Gravelle has come around to believe that Vicious was probably guilty. Savage isn’t convinced. “I think there’s a good chance that Sid actually didn’t kill Nancy, but he was so f***ed up he probably thought he did,” he says.

Similar question marks hover over Vicious’s own demise four months later. Considering he was alive when Gravelle left him the night of his Rikers release, the photographer wonders if he and Michelle Robinson may have taken an extra, ultimately fatal, dose. “She’d just come out of a psychiatric ward and was on all sorts of drugs,” he says. “I never knew if she had given him something or if they had taken Valium or something else after. She disappeared after it all happened and has never spoken about the case.”

It had gone way beyond harmless rebellion

Few refute that Vicious’ death marked the end of punk’s first era, turning its vivid colours into a memorial monochrome. “It had gone way beyond harmless rebellion,” says Scabies. Wobble considers Sid’s death “a certain marker”. He says, “You get these events, like the death of Sid and Nancy, that articulate and epitomise the end of a chapter.”

Savage sees it differently. “Pursued to one particular conclusion, it was self-destructive,” he concedes. “But it wasn’t the only side of punk, not at all. There was the do-it-yourself side. There was the creative side. It creates an explosion in fashion, in writing, in music. On an artistic level, it was incredibly successful and stimulating. It wasn’t just a whole load of nihilistic s***.”

What does Sid Vicious mean in 2024? “A T-shirt,” Savage says. “I shouldn’t think he means very much, except an image.” Cautiously, Wobble places Vicious in “this quite one-dimensional world of the icon… like a religious figure. Like Lady Di or Jimmy Dean or somebody”. But there’s a sense already that current and future generations might start to reassess this problematic figure: to shift Sid Vicious out of the pantheon of cult anti-heroes and into the realms of cautionary historical tale.

“He falls into the romantic category, for sure,” says Wobble. “Living fast, dying young in a world that could never accept that mercurial talent, all that kind of stuff. [He and Nancy] almost died together, he died to be with her. It’s very romantic. Isn’t it? But it’s a dangerous thing, you can’t see it too much that way.” To Wobble, Vicious is, to some extent at least, the ultimate victim of the zeitgeist – prey to the dark machinations of a music industry long designed to chew ’em up and spit ’em out.

“He wasn’t equipped to deal with that world, those people,” he says. “Sometimes people just astound you at their cruelty and ruthlessness and connivance.” Ultimately, Vicious might be most fairly remembered as a piranha thrown to sharks. “It was very difficult,” Wobble argues, “for a kid like that to survive it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments