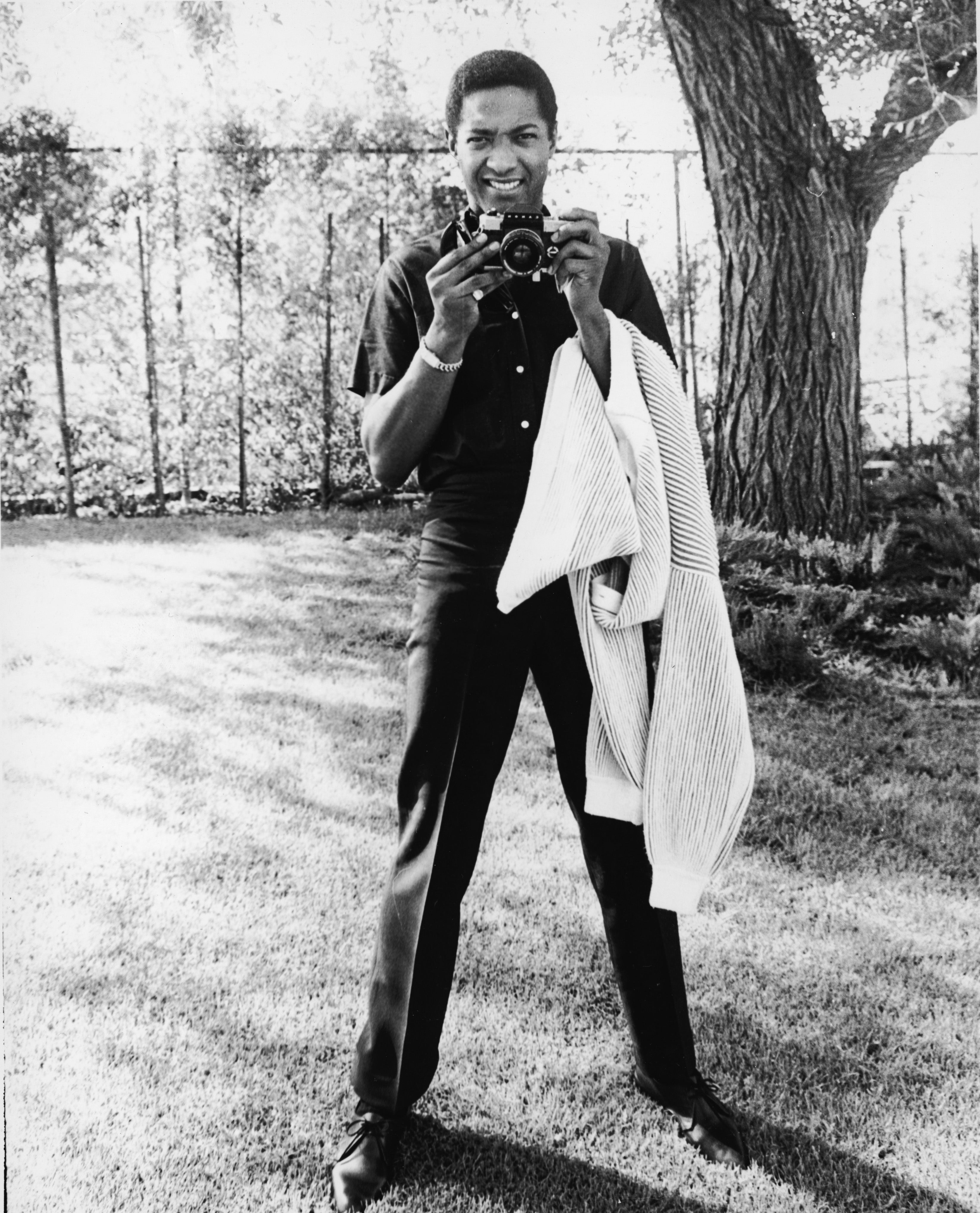

Sam Cooke’s shocking death left a lot of questions – but nothing can overshadow his music and message

The soulful Sixties crooner was 33 when he was shot by the manager of a $3-a-night motel in Los Angeles. The lingering conspiracies surrounding his death, writes Mark Beaumont, threaten to overshadow a life of music and civil rights activism – not to mention a voice that would go on to influence Otis Redding and Tina Turner

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rarely has the manner of a man’s demise been so unbefitting of their life. On the evening of 10 December 1964, soul sensation Sam Cooke dined with friends at Martoni’s restaurant, the Los Angeles hangout of Hollywood A-listers and those that fed off them, flagrantly flashing around the $5,000 in cash he’d made from recent tour dates. After several drinks, he began chatting with a young woman at the bar. Later, he failed to show up at the nightclub his friends had gone to.

Instead, in the early hours of the next morning – 60 years ago this week – Cooke was fatally shot by the manager of the Hacienda Motel, a haunt of sex workers and pimps, amid accusations of kidnap and violence. His killing would eventually be dismissed as “justifiable homicide”.

Such a shocking death, at just 33, for a man considered a gentle and high-class character by those who knew him best, inevitably led to alternative theories. That Cooke was the victim of a honeytrap sting. That he’d been murdered by mobsters muscling in on his lucrative SAR Records business, or killed by his manager Allan Klein, whose shady dealings Cooke had recently uncovered. Or that the FBI, having kept Cooke under surveillance due to his prominent and powerful position in the civil rights movement, had a hand in his untimely death.

Out of the murk, however, swiftly drifted away the real significance of Cooke’s life. Just 11 days after his death, the single “A Change Is Gonna Come” was released, a final showcase for one of the greatest soul voices of its generation and a cry of hope and defiance from the sharp end of American racism and segregation. “I go downtown, somebody keep telling me ‘don’t hang around’,” Cooke sang over noble orchestration, “... but I know a change ‘gon come.”

He might have been most famous for playful shake-shack tracks like “Twistin’ the Night Away” and “Wonderful World”, or heartfelt soul devotionals such as “Bring It On Home to Me” and “Cupid”, but “A Change Is Gonna Come” would become Cooke’s defining moment, an empowering farewell message from a loud and high-profile champion of African-American emancipation; a song that would help rally and galvanise America’s Black community for the struggles – and victories – to come. Six decades on, it still resonates today.

“At the time, it wasn’t a hit,” says Daniel Wolff, one of the authors of You Send Me: The Life and Times of Sam Cooke. “It became better known after he died. The significance now, I can’t overstate. It’s not even a protest song, that narrows it too much.” Cooke wrote the song in response to Bob Dylan’s hit protest song “Blowin’ in the Wind”, but Wolff considers Cooke’s song more important. “‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ isn’t emotional… it isn’t a soul song in that it speaks to more than just your brain. ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’ does that.”

With so many questions surrounding his death unanswered, it’s vital to Cooke’s many fans and champions that the events of his death not overshadow his music and message. His voice, after all, would go on to influence Otis Redding, James Brown, Tina Turner and Stevie Wonder. His story, meanwhile, was one of righteous bravery in the face of discrimination, and an inspirational forerunner to the great hip-hop business empires of today. Having sung with his siblings at the Chicago church of his Baptist minister father from the age of six, Cooke’s crystalline, high-flying tones saw him picked in his teens as the lead singer in gospel heartthrobs The Soul Stirrers, a kind of god-fearing *Nsync who regularly turned churches into mini-Shea Stadiums.

“When Sam and the Soul Stirrers came to [a] church, you would’ve thought they were gonna have a rock concert there,” fellow Fifties singer Smokey Robinson recalled in the 2019 Netflix documentary ReMastered: The Two Killings of Sam Cooke. “There were women who had never even thought about going to church until Sam and the Soul Stirrers were there, and they would be around the block four deep.”

Cooke had the looks of an angel and a voice to match. His vocals were a sensation; a sweetly seductive trill that could burn with a passion when really fired up. “It had an interesting emotional range,” says Wolff. “It could be very light in the pop stuff, romantic, and then it could be harsh. When you hear Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963 [a recording unreleased until 1985], or “Bring It On Home to Me”, there’s a gospel rasp that he had. And, of course, he could do what they called his yodel, that ululation at the top of his range which was distinctive, his signature.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Soon enough, the siren call of the devil’s music lured him towards the rock’n’roll rapids. “There was a potential in crossing over in pop music and rock’n’roll that wasn’t there in gospel,” says Wolff. “He’d kind of reached the top of gospel. Pop music offered the possibility to reach a new audience and talk about other things.” (Cooke, though, did not give up on religion. Later in life, amid his burgeoning friendship with Malcolm X, he became increasingly interested in Islam.)

Cooke was an instant success in the pop sphere. His 1957 debut solo single “You Send Me” launched him directly to the top of the US Billboard chart where he’d remain a Top 40 mainstay for the rest of his life. The early Sixties saw some of his biggest hits in the shape of study hall swoon tune “Wonderful World” (“Don’t know much about history…”), Hallmark soul classic “Cupid” and “Twistin’ the Night Away”, his infectious but calculated cash-in on the twist craze.

The second biggest hit of his career, though, was 1960’s grittier “Chain Gang”, a catchy number about hard labour that gave listeners an early hint of Cooke’s growing interest in political matters. The song’s amenable handling of a contentious topic was evidence of Cooke’s nous in appealing to both white and Black audiences simultaneously. “He’s talking about an almost grotesque aspect of American politics and race politics,” Wolff says, “but in a way that he can cross over with it, that people aren’t offended.”

Cooke’s growing fame in mainstream pop (his $100,000 RCA Victor deal in 1960 would be worth $1m [£780,000] today) made him a de facto pioneer of civil rights in popular culture. It was a role he wholeheartedly embraced. When the KKK threatened to attack the theatre in Atlanta where Cooke was making an appearance on the influential Dick Clark Show in 1958, Cooke stood his ground, potentially putting his life on the line to perform. Similar stands and principles powered much of his rise.

I’ve always detested people of any colour, religion or nationality who lack courage to stand up and be counted

He was the first performer to wear his hair in its natural afro state, rather than slicked back in imitation of the blue-eyed crooners. On one tour of the southern states, when police stopped his tour bus to arrest backing singer Dionne Warwick for being rude to a white diner waitress, Cooke politely but firmly ejected them from the bus. And when booked to play to a segregated audience in Memphis, he refused to play, even attempting to muster a boycott of the show. “I’ve always detested people of any colour, religion or nationality who lack courage to stand up and be counted,” he said in 1960. “I hope by refusing to play to a segregated audience it will help to break down racial segregation.”

Such attitudes made him a figure of defiance among America’s Black communities, even while he remained a butter-wouldn’t-melt teen idol to white audiences. “Whether it was teenage girls who just thought he was delicious, or teenage boys who thought ‘this is great music’, it changes your perspective [on race],” Wolff argues. “When people tell you ‘those people’ aren’t important, you go, wait, there’s Sam Cooke. He was important. Something’s wrong with this formula.”

Cooke’s activist leanings brought him into the orbit of Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, and thereby to the attention of the FBI, concerned about their burgeoning power and influence. Meanwhile, he launched his own SARS Records label and publishing company in 1961 in an attempt to own and control his music, a proto-Swiftian move that – alongside Berry Gordy’s Motown label – set a music empire blueprint for countless rap moguls to come, but it also attracted mafia interest. Around the same time, Cooke’s manager Allan Klein had finagled the company under his own ownership without Cooke’s knowledge. While bedridden with illness in December 1964 – and still heartbroken over the death of his two-year-old son Vincent in the family pool in 1963 – Cooke uncovered Klein’s nefarious dealings among his paperwork and vowed to sack him the following week. Sadly, he wouldn’t survive the weekend.

Amid such a tangled web, the true events of Cooke’s death will never be known. The woman he met at Martoni’s and drunk-drove to the Hacienda Motel that night was 22-year-old Elisa Boyer. Later to be arrested on prostitution charges, she told police that once they’d checked in as man and wife she became convinced Cooke planned to rape her, so grabbed her clothes (as well as Cooke’s trousers containing the $5,000 in cash) and fled, calling the police from a street phone to report her kidnap. Wearing just a sports jacket, a furious Cooke was reported to have been shot through the heart by motel owner Bertha Franklin in self-defence as he allegedly attacked her, convinced she was shielding Boyer. His final words: “Lady, you shot me.”

Friends and family of Cooke simply don’t recognise the violent and abusive character at the centre of this story. “He wasn’t that type of person to attack somebody,” his sister Agnes Cooke-Hoskins said in 2005, “he was a lover.” His studio engineer Al Schmitt agreed. “He wasn’t that kind of a guy that had to be domineering or have power over people,” he told the Netflix documentary. “I never saw that in Sam.”

That this was about a Black man who didn’t know his place and to stop him he had to be murdered

Such dissonance has given rise to alternative theories. According to The Boston Globe associate editor Renée Graham, his politics and popularity made Cooke a target. “Elvis believed that there was a sense in the music industry that Sam was getting too powerful and had to be stopped, which echoed what a lot of people in the Black community thought,” she told the documentary. “That this was about a Black man who didn’t know his place and to stop him he had to be murdered.”

All attempts at uncovering any additional information were scuppered by the fact that the LAPD, initially unaware of who Cooke was, decided that his killing wasn’t worth anything but the scantest investigation. “The attitude was, ‘Oh well, another n***** got shot’,” Norman Edelen, one of few black LAPD officers at the time, told People in 2021.

Thankfully, in the decades since his death, Sam Cooke’s legacy has far transcended his ignominious passing. Wolff cites Cooke as the great-grandfather of today’s industry-savvy conscious rappers. “Sam Cooke is the precursor of politically aware, musically astute performers, Black and white,” he says, pointing to the new Kendrick Lamar album as a direct descendent of Cooke’s efforts in expanding the thematic and stylistic possibilities of African-American artists. “Sam always thought there was more room and more range for a performer, especially a Black performer, and Kendrick Lamar is one of the people who’s the fulfilment of that promise. At its best, [Cooke’s] was a vision of pop music that said ‘people have to figure out a way to get along, this music can help them do it’.”

His name has been showered with posthumous awards and accolades, from Hall of Fame inductions to Lifetime Achievement Grammys. His songs have become part of the bedrock of pop culture with his heaven-scraping voice – the epitome of sweet soul sonics –celebrated as among the finest that ever sang. To this day, “A Change Is Gonna Come” is hailed as an anthem of the ongoing struggle for equality in America. “It was a long time coming in 1964,” Graham said, “and it is the shame of this nation that that song should still be so relevant.” The change might be slow in coming, but Sam Cooke’s immortal voice will forever be willing it on.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments