Royal Blood: ‘My appetite for hitting the self-destruction button began the moment I started drinking’

The British duo were dubbed the ‘saviours of rock’ but behind the scenes, frontman Mike Kerr’s addictions were spiralling out of control. Now they’re back from the brink and have found salvation from an unlikely source... disco, they tell Mark Beaumont

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Of the many crunch points that made Mike Kerr realise that rock’n’roll was sucking him under, one festival in Cincinnati stands out. “I just can’t believe I played that drunk,” says the Royal Blood bassist. “We decided it’d be fun to do a shot every five minutes before the gig, and we had about half an hour ‘til the show. So we got the clock out, five minutes, shots. Then the stage manager comes in and says ‘the rain has delayed your stage time’. So we keep going.”

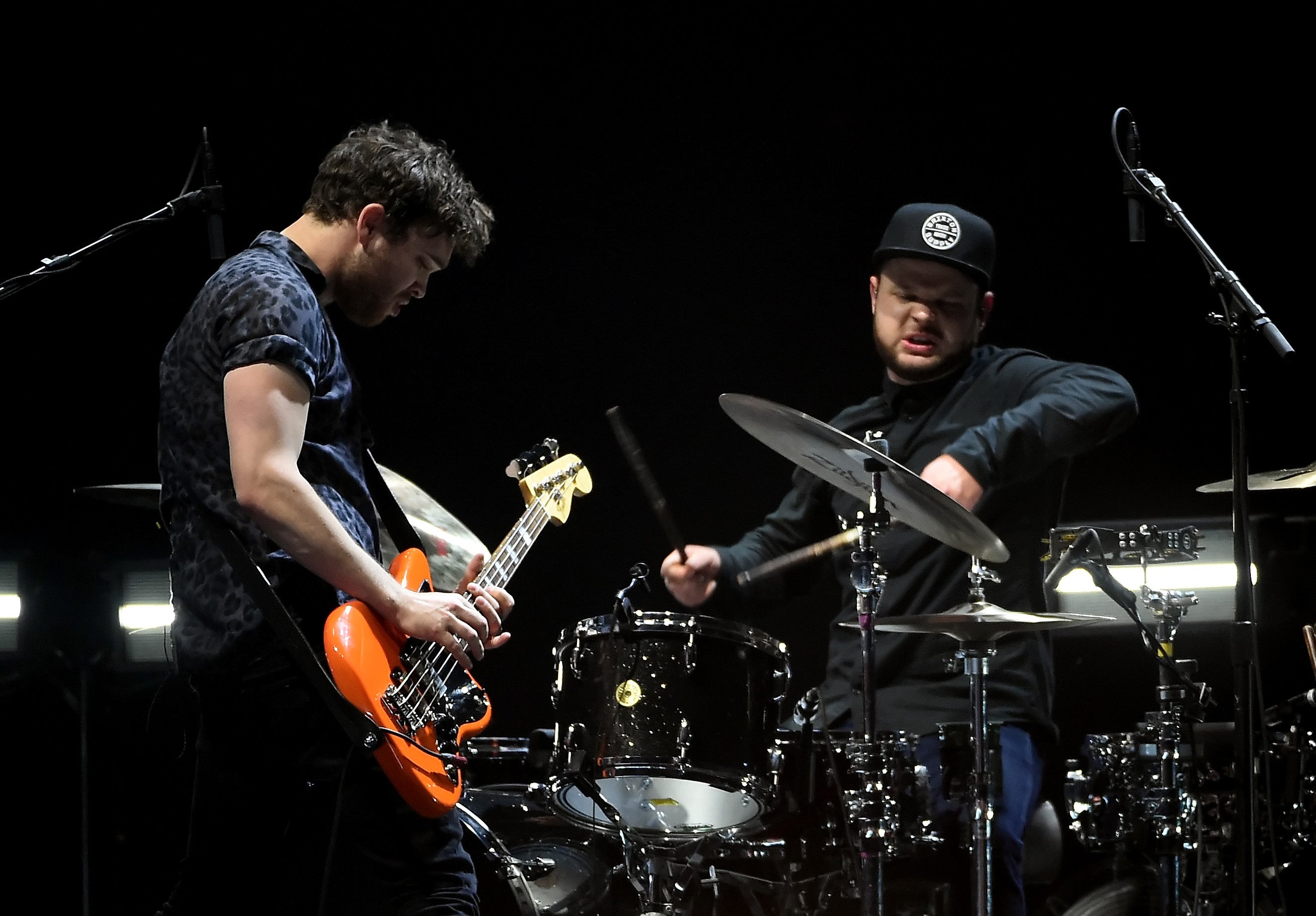

An hour later, Kerr and Ben Thatcher, his powerhouse drummer bandmate, took the stage with the rest of the bill gathered to watch the car crash through their fingers. “I was so out of it at that point, we became a spectacle to the other bands,” says Kerr, “like, ‘Royal Blood have been doing this thing, let’s go watch to see if they could do it’. That’s why it’s quite scary… it was fine. We played absolutely fine, things went great. That’s where the idea of ‘functioning’ comes in. To me, at the time, I’d have been like ‘I’m fine because I can still do that’. But actually it’s like, ‘you’re falling apart’.”

Over Zoom from a Tudor-beamed home studio, with Thatcher providing largely silent support from a separate window, the Royal Blood frontman seems bright-eyed and enthused, his striking features – eight hard-partying, shot-chaining years and two number one albums on from their emergence as Brighton’s visceral two-man rock rescue unit in 2013 – seemingly untouched by the withering finger of excess. His lockdown has been “liberating”, productive and “the best thing that could’ve happened to us”, his idle noodlings around new ideas developing into “five of the best songs” on their new, third album Typhoons. Following our chat he’s due to have his first A-list Zoom session with none other than Elton John, for his Beats 1 radio show Rocket Hour. “I reckon it’s the disco he’s into now,” Kerr grins.

Yes, disco. On Typhoons, Royal Blood’s trademark volcanic blues-rock – famously the sound of Kerr summoning an entire Queens of the Stone Age out of one bass guitar – often comes set to a revitalising, dancefloor-friendly beat, both muscle memory from when Thatcher used to drum in a wedding band in his pre-Blood days and an attempt to bring their raging afterparties, soundtracked by contemporary R&B, onstage with them. “We’d have these amazing rock shows and then have these amazing parties on the bus where it went on all night,” says Kerr. “It’s the kind of music we made when we were 15, [when] everything was very ironic and taking the piss. So it felt like a bit of a return for us. It felt like such a small reinvention on paper but it felt so fresh, like we’d tapped into a whole world of our playing and our personalities that had never been woken up.”

He says that they let go of pressures, preconceptions and “these ideas of what we should be or what people think we should be, what we’re allowed to do. It felt like we just opened our wings up, like, ‘what if we actually did whatever we wanted, what would that sound like?’ It was a weird counterpoint where the music was really upbeat and uplifting, almost as an antidote to how miserable and bleak everything was outside.”

And, historically speaking, inside. Scratch a glitter-nail’s width beneath the surface of Typhoons and you discover a breakdown you can dance to. In February, Kerr posted an Instagram photo of his sobriety coin to mark two years since his last drink, but Typhoons is set deep within his darkest days. “In my reflection I see signs of psychosis,” he sings on lead single “Trouble’s Coming”. It was inspired by recurring nightmares and concerning “what it’s like to be lost in thought and lost in depression and lost in my own head – I spent so long in this fuzz, in this washing machine of negativity,” he says. Elsewhere, thoughts become “parasites” and paranoia, addiction, meltdown and self-hatred abound. On “Oblivion”, Kerr declares “my personal apocalypse finally arrived”.

What started his spiral into the abyss? “I think it’s something that crept up on me,” Kerr confesses. “It wasn’t sudden. I personally believe that I was always heading for that, no matter what had happened in my life, whether I’d been in this band or not. My appetite for hitting the self-destruction button began the moment I started drinking and smoking – I believe that story began there.” The band’s head-spinning rise from a casual Brighton side project to Arctic Monkeys stablemates to chart topping “saviours of rock” with their self-titled 2014 debut album, Kerr believes, merely accelerated the inevitable. “The fact that what happened to us did, and the kind of lifestyle that that serves, acted as a catalyst for what was already going to happen. It just sped up the process.

I’ve thoroughly tested that way of life. It didn’t make me happy

“It’s a job role where you can go very undetected. If I was doing another job it perhaps may have been more obvious that there was an issue. If you’re the lead singer of a band you[r problems] can definitely go unnoticed… It may be something I was born with, it could be an illness I accumulated as my life went on, it could be circumstantial, I’m not too sure. All I know is that I don’t need it, I’m better without it. I’ve thoroughly tested that way of life and it didn’t make me happy, it didn’t check out for me.”

Songs such as “Oblivion” and the title track (about “how debilitating a negative thought pattern can be… how a state of mind can shut your whole body down and feel like it’s killing you”) hint that other addictions were also at play. “Yeah, drugs as well,” Kerr admits. “I don’t see a distinction between alcohol and drugs. It’s like Chris Morris in Brass Eye going ‘It’s not a drug, it’s a drink’. It makes me laugh when we say ‘alcohol and drugs’. You’re still on drugs if you’re drunk.” What sort of thing were you taking? “Everything. Anything that would get me high basically. I never did heroin.” A wry smile. “There’s still time.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Over the years, Kerr has joked in interviews about his on-tour intake, recalling having to hide from long-term Blood champion Josh Homme (who also produced their new single “Boilermaker” in his LA studio and has been known to adopt the odd disco strut himself) in a backstage toilet to avoid being plied with tequila and dragged onstage with Foo Fighters to down bottles of champagne. But, as the old rock’n’roll cliché goes, the problems really began when the road ran out but the hunger raged on.

“It was more coming home and attempting to sustain that on a Tuesday, on a normal day,” he says. “Part of this process for me is realising that I’m the problem. Beer isn’t the problem, it’s me, it’s my relationship with it that’s toxic.” On the dramatic “Limbo” he sings, “I’ve become someone I don’t recognise, I despise”. Who had he become? “Just not myself. Things I would say, places I’d be, people I’d hang out with, just everything. Waking up in the morning and being ashamed of all the things I said, and not recognising that person, but by the time the day rolled around I was that person again, living in this weird state of the two.”

Judging by the track “Who Needs Friends” (“constant creatures all around me…I got cheapskates on my right, vultures up ahead”), Kerr stopped being able to trust the people he met. “Success, for me, created a lot of paranoia. And being in the state I was in, I became unable to identify who was for me and who was against me. I now can make that distinction and it seems quite comical to me how lost I was in that. I think that’s why [fame] can be a lonely experience. Me and Ben are super grateful we’re not famous. We feel like our music’s famous, but the idea of being can’t-go-outside famous must be so lonely, and that feeling of not knowing who’s real and who isn’t must be extremely toxic. There was definitely a point in my life where I isolated myself as a way of protecting myself from that.”

There was no one breaking point for Kerr, just a gradual erosion. Until the music began deserting him. “They say rock bottom’s when you stop digging,” he grins. “I think I had to just keep coming back to that place and being hit over the head a few times. But I just gave up on the whole thing really. It’s almost like I surrendered to it. It wasn’t working and one of the biggest symptoms that scared me was my songwriting ability was slipping through my fingertips. I didn’t feel confident, I didn’t feel like I knew who I was, I didn’t feel like I had the skillset to write songs and keep this band going.”

The idea of losing that gift, he continues, was “really scary. So I think that was a big wake-up call…I clearly wasn’t very happy and I wasn’t very creative and I realised that those two things for me feed off each other. When I was making the second album [2017’s How Did We Get So Dark?] I was really unhappy and everyone kept telling me ‘it’s gonna make a great album though, it’ll be really inspiring for you to be in this dark place’ and it wasn’t. It was actually f****** debilitating.”

Kerr’s sobriety came about almost of its own accord, without going into rehab, although, he quips, “I sort of wished I did because I heard that you can go and do it in Barbados with horses.” Instead, not feeling he had a problem, he started what he thought would be a short-term detox with the help of an app. “You have to write what’s your reason, what was the goal. What I wrote was, I want to prioritise my happiness and my creativity.” A month became six weeks, became a year, then two. “I don’t attend meetings or anything,” he says. “I essentially did it through the help of friends and family and support…I’m really grateful that I’m sober and clean this young, because I think it could have taken a lot longer to get to that realisation that I needed to stop.”

The record ends on a supportive note, with “Hold On”, a message of solidarity to a struggling friend and austere piano ballad “All We Have is Now”, “another example of us not censoring ourselves,” says Kerr, and a fatalistic vow to make the best of a flawed life while he can. And with such a care-shedding party feel to much of the album, it should be quite cathartic for Kerr to dance away his hard times onstage. Part of his own personal form of 12 steps, in fact. “Shame there’s eleven tracks,” he laughs.

He doesn’t mind releasing Typhoons outside of the touring whirlwind, however. “For the first time I feel like a spectator of the record rather than being in the middle of a tour and being completely consumed by what we have to do that night,” he chuckles. “I feel like I’m at my own rocket launch.” How, two years sober, did he get so light? “I’m happier than I’ve ever been,” he smiles. “It doesn’t mean that life’s easy, I’m still a human being but I feel I have the ability to cope with life a lot better. I feel creativity. I feel present, which is really important if you’re a creative person.”

After years of grasping for the crux of his problem, now Kerr considers the crux of the solution. “Being in the moment and allowing yourself to have actual feelings,” he decides, firmly. “Rather than drowning them.”

Typhoons is out on 30 April.

If you have been affected by this article, you can seek confidential help and support from Frankon their website, by calling 0300 123 6600 or texting a question to 82111, or emailing frank@talktofrank.com (the reply email will not have your question in it).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments