The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

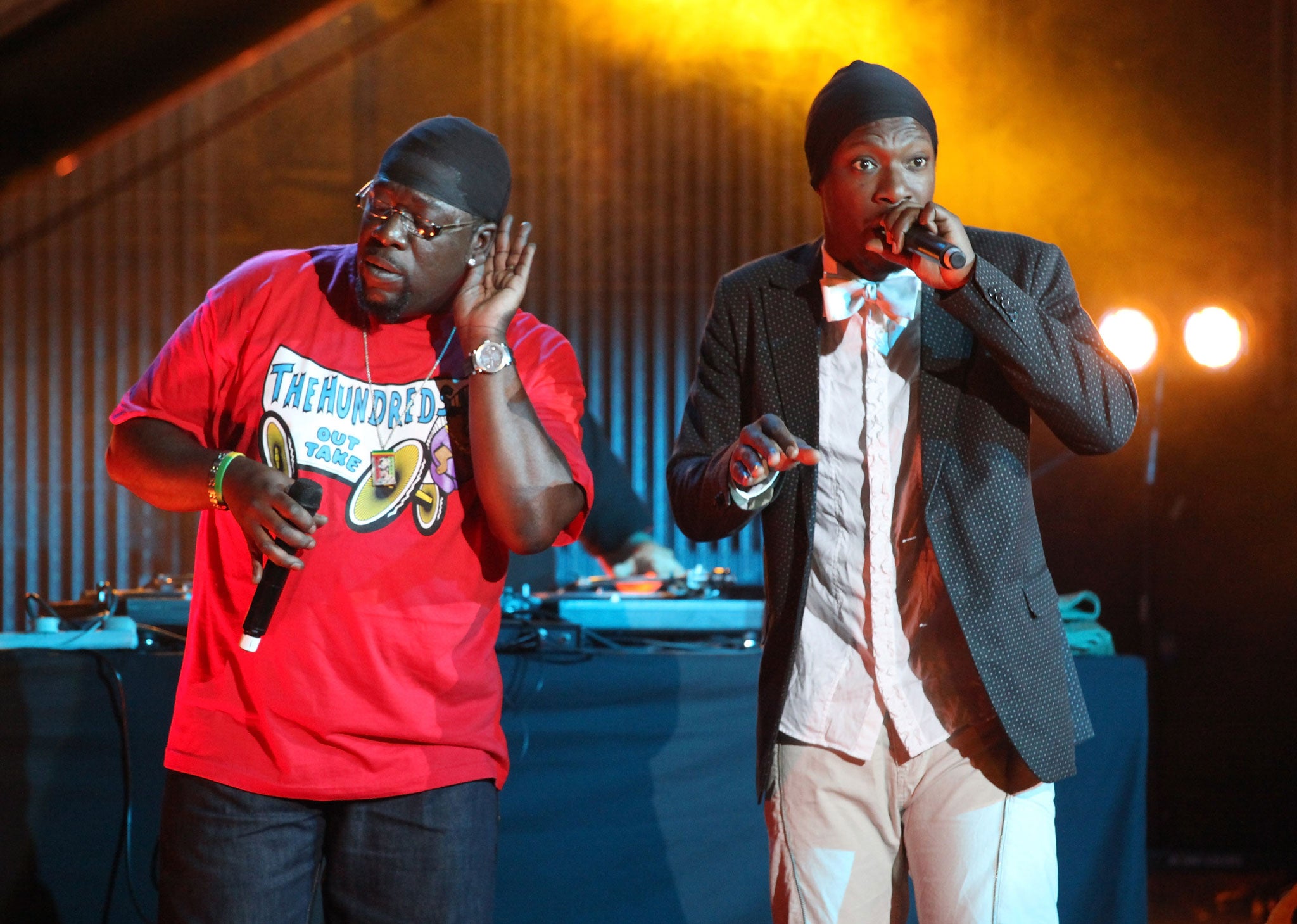

Roots Manuva interview: Why Britain's greatest rapper swapped London's Tottenham for leafy Surrey

Roots Manuva was a British hip-hop pioneer who once rapped about his skunk-fuelled hallucinations. But now the 42-year-old Rodney Smith is living (and gardening) in Esher, has he become all that he dreaded?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.According to his Twitter feed, Roots Manuva needs a hoe. That's not hip-hop slang – he means a garden hoe. The rapper, who grew up in inner London but now lives in leafy Surrey, has been trying his hand at horticulture. So far, he's taken to it like an elephant to a surfboard. "I've got the worst name for someone who can't make anything grow," he hoots, "but I can't do it. My shit does not grow! Whatever I plant, the animals seem to eat it!"

It seems an odd juxtaposition, the streetwise rapper in a garden centre, where "real shit" is something you buy in bags to spread on your flower bed, but in Manuva's case it makes a kind of sense. He has always been a nonconformist and an eccentric. So at a time when suburban youth is flocking to the inner city to live an urban lifestyle, Manuva, a totem of the lifestyle they aspire to, has moved in the opposite direction (to raise his children, though he is very protective of them and unwilling to discuss specifics).

Today, we are not in Surrey. We are in a meeting room at the offices of his record label, Big Dada, in Kennington, south London. It is a stone's throw from where Manuva grew up as Rodney Smith, son of a Pentecostal preacher. "My dad tells me there was a party of some kind on our street every weekend from when I was a baby until I was about six," he muses, gazing out of the window at the concrete skyline. "I basically lived on a well-ordered 'front line' of a kind, but there was never much trouble – everyone seemed to get on with it. Within the space of 20 terraced houses on my street, there were so many people living in overcrowded spaces, but still surviving and managing to be civil while lord-knows-what was going on – gambling rooms, front-room cafés, home factories, domestic nightclubs, maybe even brothels; though nobody seemed to complain. It really makes me wonder: where has general interpersonal tolerance gone?"

I do not have an answer for him. We sit down opposite each other. Smith is dressed all in black and looks much younger than his 42 years, albeit with a Clooney-esque touch of grey at his temples. He is quietly spoken, his booming voice only revealing itself on occasions when he becomes animated about music. Personal details trickle through at his own pace, but rarely in response to direct questions about his life – which tend to yield opaque replies, subject changes or jokes.

He tells me he moved to Surrey "as someone who has stamped his foot into being a proper forty-something parent. But because of the internet, and the amount of time I have to travel around the world, it's almost like I don't live anywhere. I had a workspace in Tottenham, but I gave it up – because of laptops, I can work at home, although generally I have to be in London. I'm constantly staying out late…" He doesn't see himself as aspirational middle-class so much as "undefined travelling class. But in a parallel universe, I'm still in Kennington. London is still in my veins."

Rodney Smith has always inhabited a parallel universe of some kind. Since his debut album in 1999, Brand New Second Hand, which established him as a pioneering force in UK hip-hop, he has repeatedly turned down major-label cash – he refers to the majors as "the Devil" – to remain with Big Dada, an independent. "I've always wanted to hang on to the life raft of me and what's inside," he shrugs.

Rapping over bass-driven, wildly inventive electronic soundscapes, he has won much critical acclaim for his five studio albums. Arctic Monkeys cite him as an influence. Usain Bolt is a fan. Yet mainstream success has remained elusive. His 2001 single "Witness", often voted the greatest UK hip-hop tune of all time, peaked in the UK singles chart at number 45. The highest he has ever been is number 28, as a guest on Leftfield's 1999 single, "Dusted".

Thanks to his global fanbase, his albums sell hundreds of thousands, but he remains an outsider. His collaborators away from hip- hop have sometimes confounded expectations, too – Damon Albarn (with Gorillaz), but also Jamie Cullum, Skin from Skunk Anansie and indie darlings the Maccabees. Roots Manuva is UK hip-hop's biggest contrarian.

Anyone worried about the effect Surrey life might have on his creativity will be reassured by his new double-sided single, "Facety 2:11/Like a Drum", on which his serene lyrical flows are underpinned by vortexes of glitchy rhythms. They are the first, highly promising, releases from his as-yet unfinished sixth album. "I just needed to say hello again," he says.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

It has indeed been a while. His last album, 4everevolution, came out four years ago. Since then, he has changed managers and begun working with a new team at Big Dada, which is taking a much more active role in shaping his creative output. "The past 10 years, I've been going off on tangents, recording at my own speed with my own funds, and presenting it back to the label and saying, 'If you like it, put it out,'" he says. Now, the game has changed. For a man used to doing his own thing, that can't be easy.

"It's been good for the music, but not for my ego," he admits. "I'm trying to be the best I can in terms of leaning on the team for support, but I'm still the artist having the tantrum – they're cutting bits of me away! I'm like, why can't we release a 60-song record?"

He reveals, startlingly, that he's recorded up to 40 versions of certain new tunes. "It's k ridiculous!" he howls. "It's not even an album in my head any more – to me, there are at least six or seven different universes of record, and they're not all me rapping to a beat. There are some things that are more rocky, or nutty electronic wordless stuff, some more symphonic studies, tribal stuff, and more high-chedelic, psychedelic, arpeggiative kind of weirdness…"

This is how he talks – in a twisty-turny vernacular that mirrors his idiosyncratic rapping style, which he describes in an email to me after we meet as "a weird concoction of annunciated [sic] ping-pong flipping between patois and London drawl and even moments of over-pronounced, refined English". He delights in such kooky wordplay – "Taskmaster burst the bionic zit splitter" goes the bizarre opening line to "Witness" – but sometimes his lyrics can be darker, apocalyptic sermons. "The misled mislead, afflicted by the greed/Government man keep fighting down the weed/While they boost up the booze, the Prozac and methadone/Use the taxpayer's money to develop they clones/Misinformation, mass sedation, nations baited for spiritual rapings," he spat on "Chin High", from his 2005 album Awfully Deep.

Smith was rumoured to have been struggling with his mental health at around that time – the album was full of references to paranoid hallucinations, medication and "kinky nurses" who "poke you in the arse". But he has never really spoken much about what he actually went through. So after we have been talking a while, I ask if his life then was as difficult as it sounded.

"I don't know…" he hesitates, momentarily wrongfooted. "The reality of that time was that it was the most financially secure I've ever been. I'd been given all this money [after the success of his previous album, Run Come Save Me, in 2001, which contained "Witness"], so the source of those lyrics came from experiences that happened before making the record. And it came from a fear of getting too comfortable, of losing my edge. My constant fear was, I don't ever want to be considered coffee-table or easy listening."

It's hard to tell where fact ends and fiction begins, listening to his work, I say. Especially as the lyrics aren't linear stories, but streams of consciousness – but sometimes he weaves in what appear to be very personal narratives.

"I'd rather not write about specific experiences," he says. "Like, on my first album there's a song called 'Strange Behaviour', where I talk about meeting a drug addict. That didn't happen to me, but I'm quite familiar with something of that nature. So the details are not always specific to a life experience… But over the years, yes, there were times when, specifically to do with medication and doctors, I was hitting the skunk weed way too hard. And I couldn't tell anybody. It got to the point where I didn't want to leave the house. There was a time when I had to be taken by management and my big brother, to see someone, to see if I was OK.

"But the whole thing with Awfully Deep was, I really liked [the dark TV comedy] The League of Gentlemen and that uneasiness, the uneasy self-deprecation and weird ha-ha humour," he continues. "So yeah, life does seep into the art, but it's not always in an obvious way."

The League of Gentlemen reference makes sense. Smith's videos are often shot through with a surreal, very British sense of humour – the video for "Colossal Insight", the lead single from Awfully Deep, had him on stage in a working-men's club channelling his inner pain through a ventriloquist's dummy. In others, he has rhymed his way through a game of village cricket, or a school sports day where he trounces the kids in the egg-and-spoon race.

Where does this eccentric streak come from? "I think it comes from having old-fashioned parents," he says. "Parents who come from rural Jamaica and have those time-leap values. They were kind of living with these Victorian values, so I've always felt… I've always had a fantasy about time travel, about being born in the wrong place at the wrong time." He has said that his future lies "in a place like Wiltshire, with a massive building, trying to turn it into a spaceship".

What impact did his religious upbringing have on his music? "My dad is a very great public speaker," he says. "As a grown man, I haven't always agreed with his interpretations of Biblical instances, but he still makes it sound so convincing and uplifting. He always encouraged me and my siblings to speak with the fullness of our voices, but before anything, he has a love for what he is saying – so, yes, memories of my dad's vocal delivery have been a massive influence on how I try to put originality and mystique into my songs."

This gets harder with age, he admits – the process becomes longer. "You become more self-conscious. There was a time when I was really into just the first take, even if it wasn't perfect. Now, it's like putting songs through a rowing machine to see how they last. But I'm getting there – I've got an arsenal of stuff ready to come out. And I think we're going to get it right because everybody feels good."

'Facety 2:11/Like a Drum' is out now on Big Dada. Roots Manuva will play select festivals this summer across the UK and Europe, and support Blur at British Summer Time, Hyde Park, on 20 June (ticketmaster.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments