Richey Edwards: The mysterious disappearance of the Manic Street Preachers star, 30 years on

The guitarist vanished on 1 February 1995 and is widely presumed to have taken his own life, but a body was never found and there is no definitive proof that he died by suicide. Thirty years later, Ed Power reflects on the rock star whose legacy is one of tragedy and conspiracy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The scars came back when he drank too much. Or so Richey Edwards explained to an interviewer in Toronto in April 1992. “It’s healing very well,” elaborated the Manic Street Preachers’ guitarist and lyricist. A fragile grin played across his face.

He proffered the arm into which he had notoriously carved “4 Real” with a razor blade the previous May. The faintest traces of the words were visible as a glowering welt. “It always comes out nice and red if he’s had a bottle of vodka,” nodded his bandmate Nicky Wire. “Brings it out in the blood.”

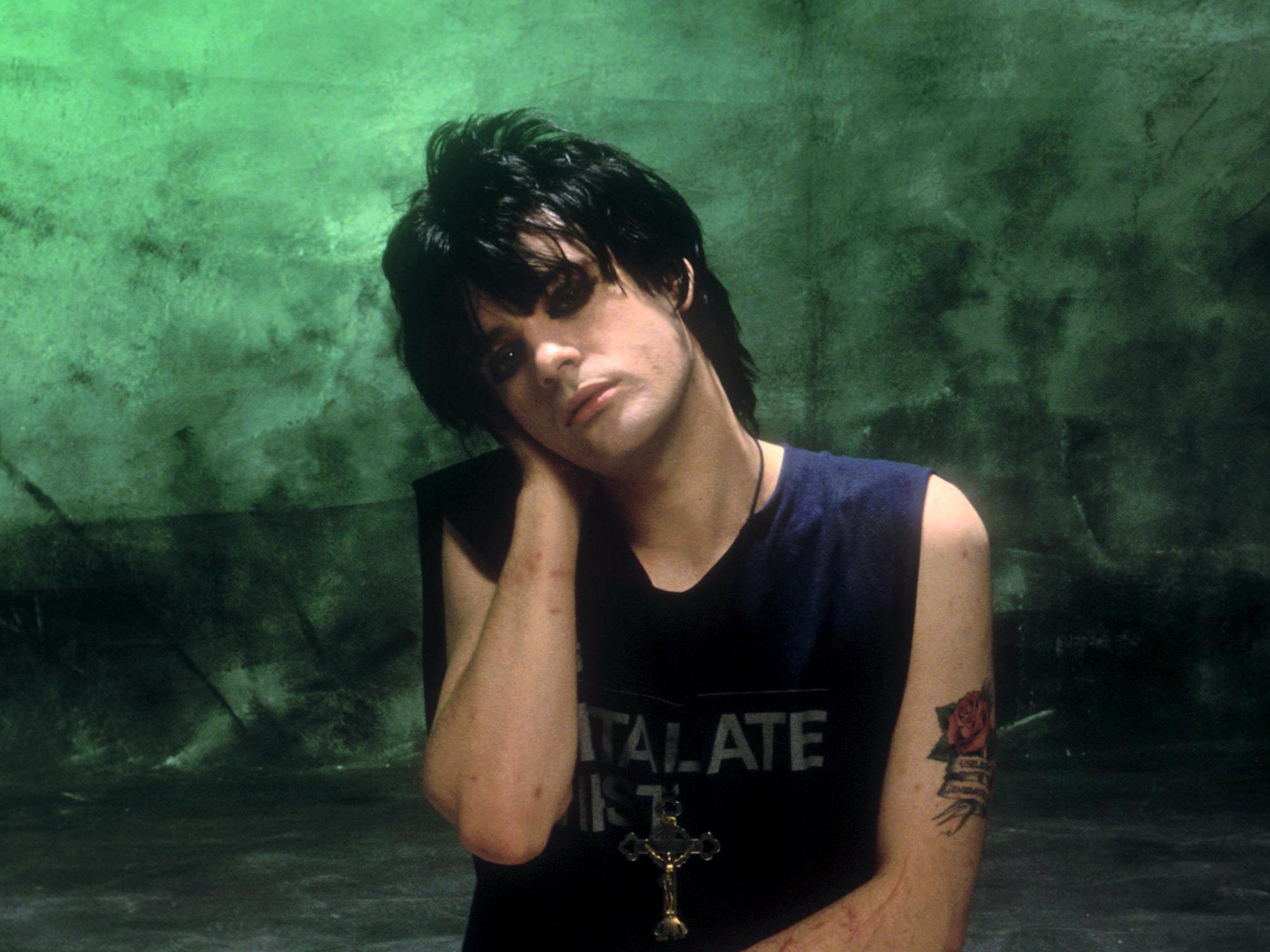

Edwards continued to smile sadly as Wire spoke. That expression of delicate amusement tipping into something bleaker was already familiar to the Welsh quartet’s fanbase, in particular the segment drawn to Richey’s gothic beauty and haunting lyrics. He was the heart and bruised soul of the group.

But today, so many decades later, Edwards is seldom remembered in this way. Saturday 1 February marks the 30th anniversary of the musician’s disappearance. He checked out of his hotel in London first thing in the morning and drove to Wales. That same day he crossed the Severn Bridge, which connects England to Wales. There, the trail grows cold and one of the most enduring puzzles in British indie rock begins.

His body has never been recovered. Edwards is widely presumed to have taken his own life at age 27 and was declared legally dead in November 2008. But there is no definitive proof that he died by suicide. And so a mystery has sprouted wings and taken flight. Just as Elvis sightings persisted years after Presley’s passing, so Richey Edwards has become the eternal spectre of early Nineties alternative rock. A tragedy and a conspiracy theory bound up in one.

The Manic Street Preachers were divisive from the outset. They could barely play their instruments when they emerged from the decaying Monmouthshire pit town of Blackwood in the early Nineties. Yet they quickly established themselves as the great arch provocateurs of their generation.

Early notoriety was gained through their calculated gibing of the London music press. The Manics claimed to have more affinity with Guns N’ Roses and Mötley Crüe than with student disco totems such as The Smiths and The Stone Roses. More outrageous yet, they bragged about wishing to sell millions of records and had happily signed to a major. When they sang the chorus to their 1991 single “You Love Us”, it was as a taunt rather than a boast.

Behind it all was Edwards, the group’s conceptualist and lodestar. “Richey was the chief lyricist, orator, poet, philosopher and media manipulator of the band,” says Sara Hawys Roberts, co-author of Withdrawn Traces: Searching for the Truth About Richey Manic.

“When we started we said we wanted to be the biggest band in the world,” Wire told me once. “It wasn’t for the money or fame – it was because we had something important to say.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

As their grand scheme took shape, Edwards was both central to the Manics’ allure and an outsider in his own ensemble. He wasn’t really a musician and rarely got involved in the studio (singer James Dean Bradfield played all the guitar parts instead). On stage, his amp was frequently turned down. He was there to be looked at, not listened to.

But there was so much to see. And with cheekbones like water flowing over sharpened rocks, he cut a strikingly, almost alarmingly glamorous figure in the early Nineties “toilet” circuit. I saw the Manics on their Holy Bible tour – their last as a four-piece – and what I remember of the gig today is Edwards giving off an eerie luminescence, like an agitated ghost.

He hugged the back of the stage, swamped by shadows. Yet he radiated more charisma than the other three bandmates combined. And that despite Wire’s attempt to wind up the audience by punching a hole in the low roof with his bass (the band’s management had insisted the venue replace pint glasses with plastic, assuming the Manics would be bottled at least once).

“We started at a time when rock’n’roll was dead,” Edwards would later say, despairing of the scene in which the band had come up. “The UK was in the grip of dance, rap, and the acid house thing. All that Manchester sound stuff that sounded so contrived... The only real rock’n’roll was coming out of America. We were consciously reacting against all that. Our friends laughed at us because they said there was no audience for us. But we felt we had to do something to bring back rock’n’roll, so that’s how the Manic Street Preachers came about.”

“He was so enigmatic on the inside and outside and played the part of the rock star so well that he drew people in with his outlook and aesthetic,” says Hawys Roberts. “He reached an audience by articulating the tragic sublime and resonated with people who felt voiceless or unable to express the way they felt.”

Four years before his disappearance, it had been the “4 Real” controversy that put Edwards on the map. It occurred at the end of an interview with the NME’s Steve Lamacq, with whom the Manics had an antagonistic relationship. Lamacq had been a cheerleader when they’d first moved to London. But things turned sour after he gave an early gig a poor review.

“The Manics were an aspiring, ambitious rock’n’roll four-piece from Wales,” Lamacq would recap in his 2000 autobiography, Going Deaf For A Living. “I was the NME journalist sent to review them. After a post-gig interview in which we discussed both their methods and their merits, guitarist Richey Edwards invited me backstage for a final word. Edwards, while still talking, then cut ‘4 REAL’ into his arm with a razor blade.”

Extraordinarily, Edwards had then pressed on with the chinwag, taking place at the glamorous Norwich Arts Centre. Lamacq watched in growing horror as the musician continued to hold forth, apparently oblivious to the blood gushing from his arm.

“By the end, the conversation was going around in circles and Richey’s arm was beginning to look uncomfortably gory,” Lamacq wrote. “The blood from the first cut had started to trickle down his arm the moment he’d finished it, until I saw the photos the next day, I didn’t know what he’d written because it was obscured by the blood. ‘We’d better do something about that... you’re going to mess their carpet up.’”

The incident contributed to their growing fame, Edwards’ in particular. But if acclaim was what he was after, he appeared to find the results both underwhelming and too much to handle. Under the spotlight, the eating disorder with which he wrestled for some time spiralled. It would inspire the song “4st 7lb”, on 1994’s The Holy Bible.

He also drank too much and eventually went into rehab. When he re-emerged he seemed increasingly isolated even from the bandmates with whom he had grown up. In one of his final interviews, he spoke of being fundamentally unlovable and doomed to be alone.

“I’ve never had any long relationship,” he said. “The longest, when I was young, was about four days. Since the band started, I’ve only really been involved with one girl. I can speak to her more naturally than to anyone else. It means something. But I’ve never told her I love her. I’ve known her for years, but I’ve only kissed her once... once, twice. That’s all. How can I explain? When I love somebody, I feel sort of trapped.”

In the end Edwards was an enigma even to those with whom he was closest. His lyrics made explicit his turmoil. Yet even as his writing turned from desolate to pitch black with The Holy Bible, the assumption in the camp was that he was taking on a persona rather than exorcising something deep within.

“I thought he was being a bit more vicarious about it all than he was,” Bradfield would note. “I didn’t assume it was all about him. It is a very nihilistic album, infused with intent and ideas and observations. We did see a lot of dark introspection there, but he was looking outwards as well.”

“The truth is, though, that we exploit our rock’n’roll stars,” commented photographer Kevin Cummins, who had snapped the Manics for several NME spreads. “We want excessive behaviour. We live our lives vicariously via theirs. Until it all goes wrong.”

So he was a young man in a dark place. Later, after he vanished, his bandmates would theorise that Edwards was too fragile for the world. He’d had a happy childhood in Blackwood, where he was cosseted by his beloved grandmother. Maybe he found the grown-up world – so uncaring and relentless – too much.

“Up to the age of 13, I was ecstatically happy,” he had said. “People treated me very well, my dog was beautiful, I lived with my Nan, and she was beautiful. School’s nothing – you go there, come back, and just play football in the fields. Then I moved from my Nan’s and started a comprehensive school and everything started going wrong. In my twenties, there’s nothing that’s been that spectacular since.”

It all came to a head on 1 February 1995. He and Bradfield were due to fly to America for a promotional tour that day. In the fortnight leading up to the disappearance, the guitarist had withdrawn £2,800 from his bank account. Rising early at the Embassy Hotel on Bayswater Road, he took his wallet, keys, passport and some Prozac. He checked out at 7am.

Two weeks later Edwards’ Vauxhall Cavalier was found abandoned at the Severn View service station. It was close to the Severn Bridge, a known suicide site. A toll booth receipt was recovered confirming he had crossed the bridge the day he vanished. He was initially thought to have driven through the booth at 2.55pm on 1 February. But this timeline has become disputed after it emerged that the tolling system uses a 24-hour clock, which would mean he had crossed at 2.55am.

Speculation that Edwards might have faked his death began immediately. Later there were reported sightings – in Goa, the Canary Islands and at Newport Public Library. This was excruciating for his parents and younger sister Rachel, his only sibling. Without a body, they could never say goodbye to Richey properly.

“The public engaged with the disappearance of Richey. They read the articles, tried to understand what happened. And they saw some of the family’s pain… it is very similar to the pain of other families with somebody missing, who might not be as high profile,” says Jo Youle, chief executive of the charity Missing People, which has worked with Rachel Elias (nee Edwards) to raise awareness of missing persons cases.

“That awful sense of just not knowing. Swinging between, ‘Maybe we’re going to get an answer, we’re going to hear from them one day,’ to hopelessness and then swinging back again to, ‘Maybe we’re going to hear.’ That ambiguity is hard to live with. As it goes into years – how do you then metaphorically walk away from that?”

Not everyone sees this as an open and shut case. “Richard’s own uncle went off the grid for 10 years when he went out to lecture in Texas in the Sixties and Seventies and this was something that fascinated Richard as a young man,” says Hawys Roberts.

“There is every possibility he could have been in Goa, there is every possibility that like his uncle he intended to return after 10 years, but who knows what could have happened in the first 10 years of Richey being a missing person. He was spotted in Goa and on the hippy trail, there’s every chance he could have been in Thailand in 2004 and sadly perished in the Boxing Day tsunami. Maybe he intended to come back but his passing was not of his own choosing. Every hypothesis must be considered when dealing with such a rare and unique missing persons case.”

The Manics, who had never really relied on Edwards in a musical sense, pushed on. They became Britpop stars with their first post-Edwards album, Everything Must Go. With Wire taking over as lyricist-in-chief, the record was more pop-oriented than anything they had recorded with Edwards. Reeling from the agony of his loss, they stepped towards the light.

“I understand why Richey would be regarded as a bit of a cult figure,” Wire once told me. “He was one of my oldest friends – we’d played football together as seven-year-olds. However, I was never really upset that people latched on to him afterwards. That’s what happens in rock and roll. As kids, I’m sure we felt the same about Jim Morrison and Ian Curtis. Rock stars who die young have always seemed glamorous.”

This article was originally published in 2020.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments