For my next number – illness and death

Forget sex and drugs, rock's newest subject is ageing, says Nick Hasted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Hope I die before I get old," Roger Daltrey declared in The Who's 1965 song "My Generation". Pete Townshend, then 20, wrote the words in the voice of a speed-gulping mod, a raging adolescent foreseeing no future.

He was keeping faith with the 1950s rock youthquake, and anticipating the hippies who trusted no one over 30. Many of rock's heroes, from Janis Joplin to Amy Winehouse, obligingly died at 27.

In 2012, one of Townshend's contemporaries, 63-year-old Peter Hammill, is by contrast singing this, on his remarkable new song "All the Tiredness": "All the tiredness that you've held in waiting, in abeyance, now comes rushing in… Though I made it through the shows, something got left behind, a debt I owe." The Van der Graaf Generator vocalist lists the inescapable exhaustion that hits the body in its sixties. This is rock's new subject, as the elixir of youth it promised fails, and its makers and listeners face decrepitude and death. When you don't die before you get old, Hammill has survived to say, this is how it feels.

"When I started playing in the 1960s," he tells me, "nothing had been going longer than five years, and it was – and largely remains – the music of youth. But once it became clear that, 'Yes, this can go on longer,' it had to start addressing the point of view of all sorts of ages, and the problems that hit."

Right from the music's start, as with Buddy Holly's "That'll Be The Day" ("when I die…") and "Not Fade Away", its wisest minds sensed a reckoning would come one day. The Kinks' Ray Davies spiked the 1960s' youthful optimism with "Where Did My Spring Go?", an account of physical decay even less sparing than Hammill's. A potentially crippling childhood injury, Davies told me, left him "feeling older… aware when I was young that it's not always going to be this good."

The Fall's Mark E Smith (who wrote "50-Year-Old Man" when he became one) and songwriter Paul Heaton, 50, have also faced up to old age early. "Fifty-fvie and 65, you wipe like spit from chin," Heaton observes on "It's a Young Man's Game". "But 75 and 85, that dribble's part of grin."

Bob Dylan's "Not Dark Yet" (1997), written aged 56, signalled the sea-change, as the spokesman for Townshend's generation glimpsed its end, not from excess, but the unglamorous aftermath. Dylan resignedly watches "time running away", resting his bones in death's antechamber, where "it's not dark yet, but it's getting there."

The final act of Johnny Cash's career is a textbook case of what rock has gained and lost as it nears its 60th birthday. The series of albums which began with American Recordings (1994) when he was 62 resurrected Cash, as an artist with no time or inclination left to compromise.

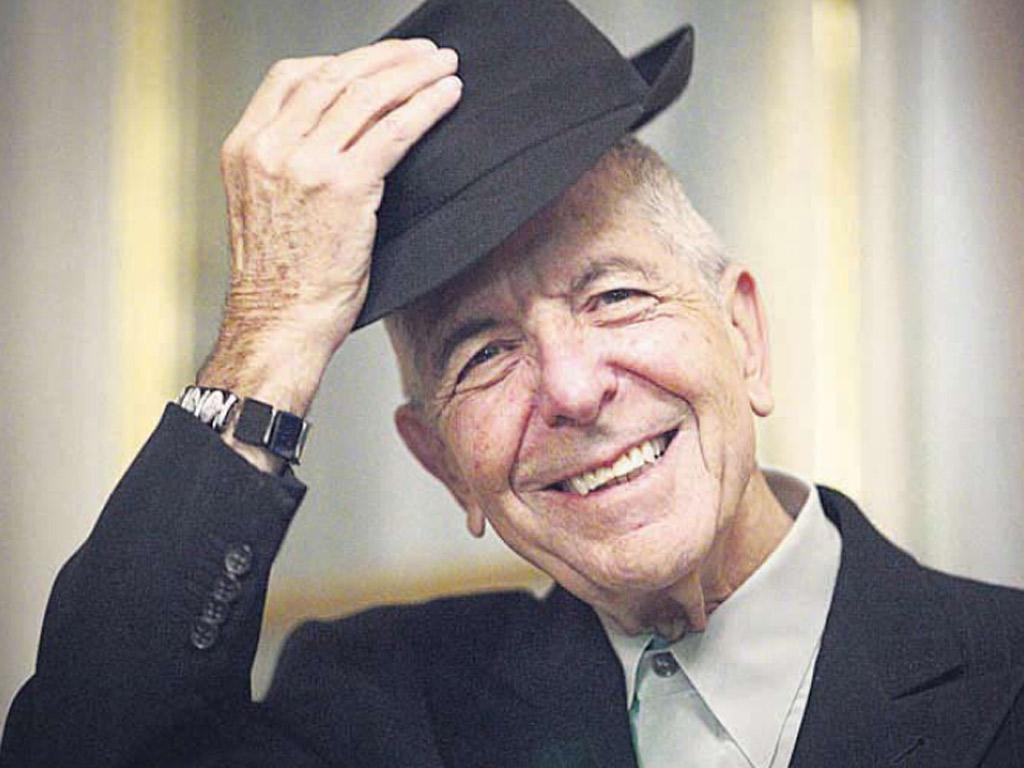

Leonard Cohen, at 78 rock's most senior citizen, came down from his buddhist mountain retreat with this year's Old Ideas, an LP whose dark wisdom feels biblical. On songs such as "Different Sides" the gentlemanly poet carves out hopeless truths about humanity with deeper fatalism than ever.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

"This is reality now," Hammill ponders. "Strangely, I feel doubly invigorated, because I've found new themes to explore – the sense of the disappearance of people, of places, of certainties. And if you reach this sort of age, your friends and contemporaries are experiencing the same things, and as a songwriter there's a responsibility to address that."

Pop as a whole still replenishes itself. But the battered visages of Keith Richards, Dylan and Cash suit rock in its dotage. Rock'n'roll will, perhaps, never die. But as we inevitably do, the music now has something to tell us about that, too.

Peter Hammill's album 'Consequences' is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments