Ray Davies - How a lonely Londoner created one of the great Sixties songs

Of all The Kinks' hits, Waterloo Sunset is the one that still casts a spell. Ray Davies tells the band's biographer, Nick Hasted, how he came to write a genuine anthem

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

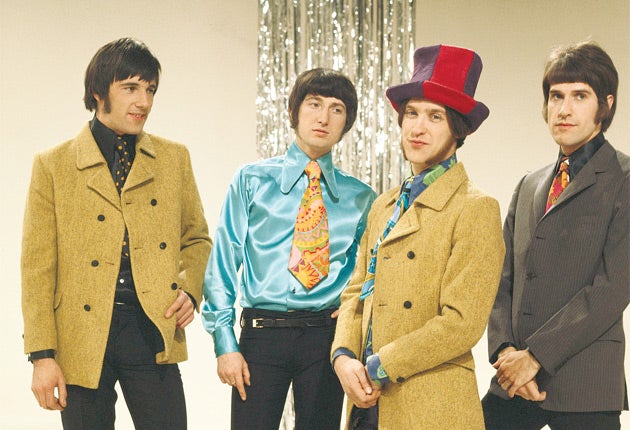

Your support makes all the difference.When I was researching my new biography of The Kinks, there were several special moments: sitting in the slightly shabby remnants of their legendary north London studio Konk, for instance, listening to drummer Mick Avory's reminiscences, while Ray Davies flitted around spectrally in the background, scarf trailing behind him like Rupert the Bear. Most magical, though, was the winter evening I spent at 87 Fortis Green, a solid white north London semi-detached house from 1829, which Ray moved into in 1965. This was the quiet suburban refuge from the Swinging Sixties where almost all his songs were written, till he moved out in 1973. I stood in the front room, facing the wall where his white piano once was. And I imagined him in 1967, on the spot where I was standing, writing perhaps the decade's greatest song.

"Waterloo Sunset" is a spell cast every time you press play, drop a stylus, or hear a minute of it on a radio. It has made millions contemplatively pause around Waterloo, a busy urban area the record gives a sacred glow. The place already had that resonance for Ray. As he told me, "Waterloo Sunset" drew on his past, spilling fragile memories.

Even if you don't quite grasp the lyrics, you catch the narrator's condition. He is a lonely, wounded animal who doesn't dare leave his room, scared by the restless flow of the Thames and the crowd "swarming like flies" around Waterloo Tube. Even the cold spring air is too much. So he contents himself with watching the young lovers Terry and Julie, and the beauty of the sunset from his window. "And I don't feel afraid," he sings, holding on to this view of "paradise". The comfort the record finds for his pain is one reason hearing it can feel like healing.

"I didn't think to make it about Waterloo, initially," Ray says. "But I realised the place was so very significant in my life. I was in St Thomas' Hospital when I was really ill [when he had a tracheotomy aged 13], and the nurses would wheel me out on the balcony to look at the river. It was also about being taken down to the [1951] Festival of Britain with my mum and dad. It's about the two characters in the song, and the aspirations of my sisters' generation before me, who grew up during the Second World War. It's about the world I wanted them to have. That, and then walking by the Thames with my first wife, and all the dreams that we had. Her in her brown suede coat that she wore, that was stolen." He laughs quietly as he thinks of that once beloved wife, Rasa Didzpetris, the mother of his first two daughters, who divorced him in bitter circumstances in 1973. "Sometimes," he continues, "when you're writing and you're really on good form, you think, I can relate to any of these things. That's when you know it's good."

The Kinks have strong memories of making their delicate masterpiece. "I remember I bought a little mini-grand piano, and I wrote it on that," Ray says. "What was missing was the sound, the arrangement."

"Ray introduced us to it in his front room in Fortis Green," says Avory. "He played it on the piano." Dave Davies, The Kinks guitarist and Ray's combative, crucial foil, who is these days estranged from his brother, remembers everyone chipping in devotedly. "Apart from the vocal lines and the guitar riff at the beginning, I think the arrangement evolved from playing it. It was Ray's song, of course. But we were all so in love with its atmosphere that every embellishment contributed to the outcome. We were charged with ideas."

When it came to recording, the song drew out Ray's perfectionism. "I did the back-track over the course of two or three sessions," he says, "in Pye No 2, a smaller studio, while making an album. I did it on the end of sessions. I said, 'Let's go back to that, and do the next bit', and gradually built it up. I tried it out at the beginning with [legendary session man] Nicky Hopkins on keyboards, and it felt too professional. So I kept it as a band track. Then I went on a separate day and put Dave's guitar down."

"The guitar playing one note at the beginning is the glue that holds it together," says Dave. "The bass and my guitar go down as the song rises. It's like tunes I loved as a kid, that went up and down like snakes and ladders – it's sad, but you know it's going to erupt into something good." A third session began with Dave, Rasa and the group's bass guitarist Pete Quaife recording ethereal backing vocals. Dave remembers their loving closeness, now long gone. "We just sang along. It was very organic. It would be lovely to be able to work like that now. Having Rasa there, that female vibe, softens the attitude of the song. It makes it warmer."

Ray added his lead vocal last, and lyrics he hadn't shown a soul. All the music had been made without anyone else having a clue what they were playing was about. It was so personal, he was frightened they would laugh. "I felt very precious about it, because I really didn't want to rewrite this," he says. "I had it all set in my head. It was all definite." "It's a song about isolation and detachment, and not wanting to be a part of the world," Dave says of its voyeuristic perspective and sad claim that "I don't need no friends", which so clearly describes teenage Ray in his hospital bed, and perhaps him as an adult outsider. "Because The Kinks never really fitted in. It wasn't just Ray's observations. It was us looking outside at a harsh world, and trying to pick out the bits of it that were beautiful and inspiring. I felt very safe in the music, and in the picture Ray was trying to paint."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

The identity of the two young lovers is one of the 1960s' piquant, enduring mysteries. Terry and Julie were thought to be Terence Stamp and Julie Christie, glamorous young stars together that year in Far from the Madding Crowd. In interviews at the time, Ray sometimes suggested this might be so. These days, he says Terry was his nephew Terry Davies, who he was perhaps closer to than his real brother in early adolescence. Dave thinks the song's secret code is even more personal. "I've always thought Ray meant him and Rasa. Ray's never been very good at emotional things. He projects them on to characters in songs."

Does Ray think so many people respond to the record partly because it draws from such a deep well of his emotions?

"I think so. The record triggers people's imaginations, as well as what they're actually hearing from the gramophone or radio. It puts people into a world. Like most things that have been around for a long time, it sounds commonplace and inevitable now. I was there when it was played back the first time, and it sounded like nothing like it had ever been done. Now I think of it, 'Waterloo Sunset' was all in the air," he says, suggesting the visionary, "waiting for someone to put it together".

Ray was still reluctant to let it be heard. He considered not releasing it at all. Instead, he pretended he had made it for his family. Its first audience was his niece Jackie, and his beloved sister Rose – Terry's mum. "That time playing it at home to my sister was magical," he says. "I think they were moved. I know Rose liked it." It was released on 5 May, as spring turned to summer. "It's the best record you'll ever make," Disc and Music Echo's Penny Valentine rang Ray to tell him, and it was.

A friend of mine remembers being unhappy in London. The air was turning into the song's "chilly, chilly" early spring, and as she saw Waterloo Bridge she sang it in her head. At that moment, a courier cycled past her whistling it too. It was the first time she felt there were people in the city with whom she might connect. When a boyfriend gave her flowers from the stall where he worked at Waterloo Station, she thought of Terry and Julie. That's the impact of this beautiful London folk song and pop record. It's why The Kinks are loved.

"It's not a question of being loved," Ray says. "I just knew, within the terms of what I was doing, that I couldn't have made it better. I'm not saying it changed the musical landscape of the world. But in the world that I inhabit, it did all the right things. It's a very innocent record. I'm proud of that. You can't beat innocence."

'You Really Got Me: The Story of The Kinks' by Nick Hasted is out now from Omnibus Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments