Quincy Jones’s brilliance goes far beyond his work with Michael Jackson

The late great music producer is best known for his work with the Eighties pop star, but there was more to Quincy Jones than ‘Thriller’. Mark Beaumont chronicles an expansive, masterly career that spanned history-making collaborations, social activism, and no fewer than 28 Grammys

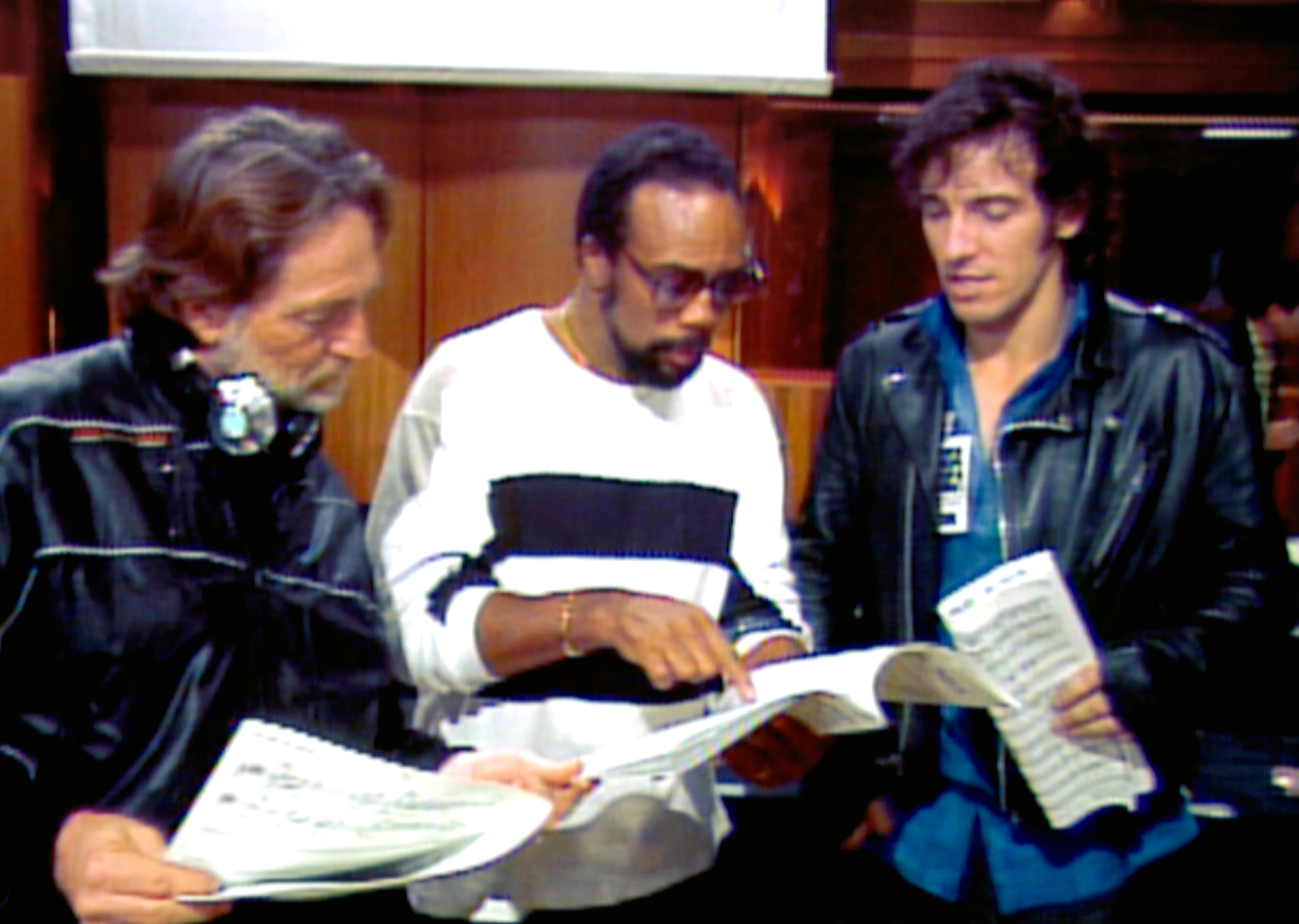

Bruce Springsteen parked up across the street and wandered through the crowds at the gate to the studio. Inside, Michael Jackson was already recording his vocal parts as Billy Joel and Stevie Wonder paid their respects to Ray Charles, and Diana Ross jumped playfully into Bob Dylan’s lap. And still they came: Paul Simon, Tina Turner, Dionne Warwick, Lindsey Buckingham, every major star in American music bar Madonna and Prince – all drawn to A&M Recording Studios to tape the USA for Africa single “We Are the World” on the evening of 28 January, 1985, marshalled by one of the fundamental figures in US music and arguably the most successful producer of all time, Quincy Jones.

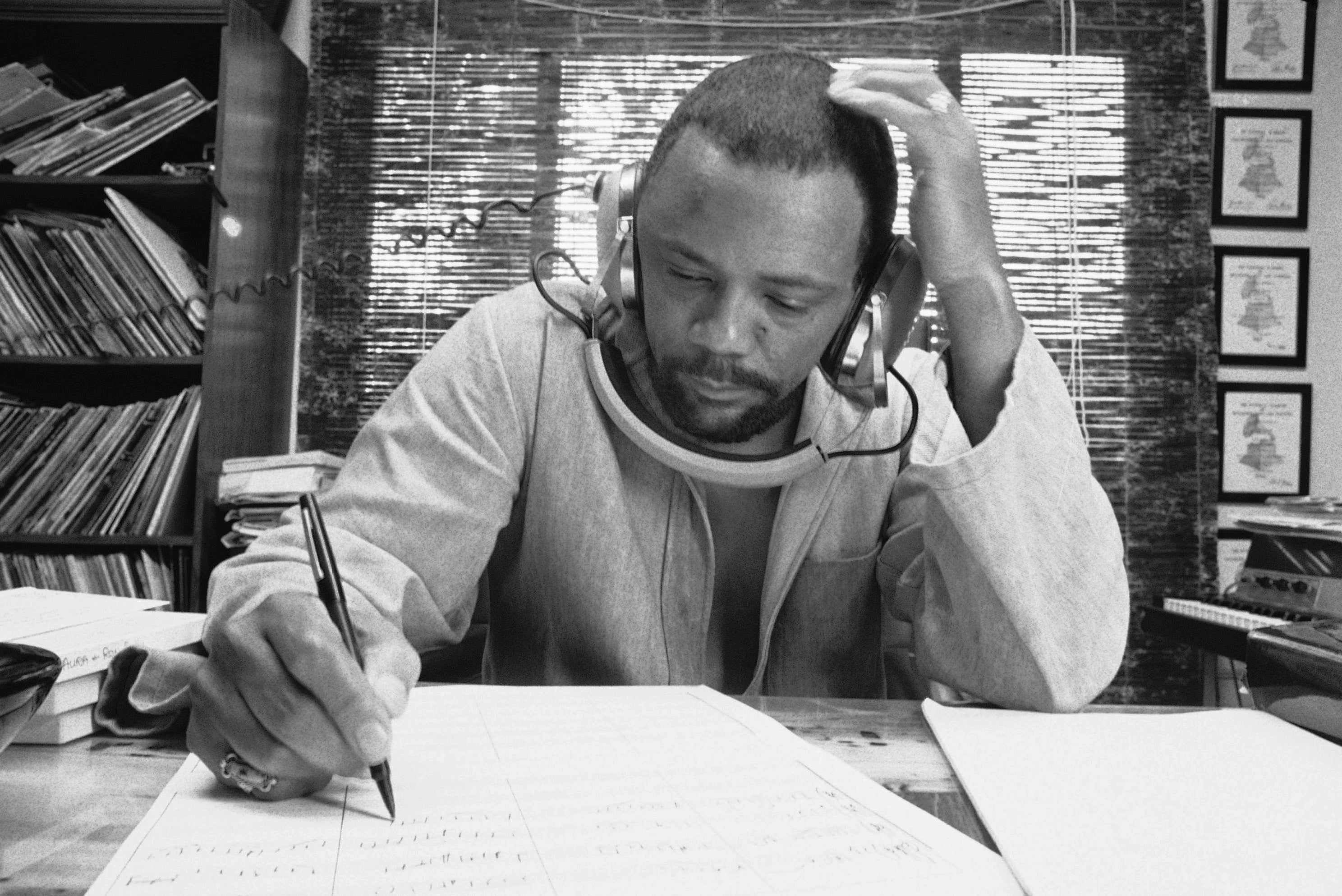

That Jones, who died on Sunday aged 91, took the producer’s chair at the most star-studded and ego-laden recording session in history – an experience he described as “like running through hell with gasoline drawers on” – is the ultimate testament to his elevated standing in the US music pantheon. His production work on Jackson’s Off the Wall, Bad and Thriller, secured his position as one of the biggest and most powerful names in production. Thriller went on to become the best-selling album ever. By then, though, he’d already kicked down numerous barriers to become a groundbreaking focal presence in American pop culture.

Born in Chicago, this shrewd and streetwise jazz trumpeter and bandleader had vowed to conquer the music industry, onstage and off. In 1961, he rose through the ranks of Mercury Records to become its first African American vice-president at 28 years old, en route to producing and playing with Frank Sinatra and a vast array of jazz and soul greats. In 2014, he listed Aretha Franklin, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Billie Holliday, Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, and Louis Armstrong among his most impressive collaborators, while the mid-Sixties singles, he produced for Lesley Gore produced four million-sellers, including “It’s My Party” and “You Don’t Own Me”.

It was just the start of a plethora of pioneering firsts for Jones who opened doors for generations of artists and industry figures. He was also the first African American to score a major film, 1964’s The Pawnbroker; the first to be nominated for the Best Original Song Oscar for “The Eyes of Love” in 1967; and, in 1971, the first to become musical director and conductor at the Academy Awards.

Jones was also considered one of the most celebrated jazz players of the Fifties and Sixties. As such, he would have gone down in history even if the brain aneurysm he suffered in 1974 had taken his life prematurely as expected. Given only a one per cent chance of surviving his surgery, he attended his own memorial service at The Shrine in LA that year alongside Richard Pryor, Marvin Gaye, and Sydney Poitier.

“It was special to see so many people there to celebrate what would’ve been my 41 years of life,” he wrote in 2018. He said that being warned by doctors never to play trumpet again, lest the clips inserted in his brain give way, spurred him on to his subsequent success. “I didn’t let that stop me from pursuing other passions,” he said. “If I sat around feeling sorry for myself, I would’ve never gone on to do Thriller, ‘We Are the World’, The Color Purple [which Jones produced and scored], or anything else that happened post ’74.”

Key to Jones’s advancement were his passion, adaptability, and determination, along with a frank and straight-talking humour that took no prisoners. In a 2018 Vulture interview, he described the early Beatles as “the worst musicians in the world, they were no-playing motherf***ers”. As for Jackson, he called the pop star “greedy” and “Machiavellian”, accusing him of pilfering melodies from the likes of Donna Summer without credit. Donald Trump, he simply referred to as a “a f***ing idiot”.

Jones’s attitude was the result of a troubled but inspiring upbringing. Descended from both slave stock and British royalty (he traced his bloodline back through US entrepreneurs and poets to Edward I of England), Jones grew up in Illinois in the Thirties and Forties in a dislocating family: his well-educated mother had a schizophrenic breakdown when he was young and would later die in a psychiatric hospital. “Brilliant lady, but she never got the help she needed,” he told Vulture. “Her dementia praecox could’ve been cured with vitamin B, but she couldn’t get it because she was Black.”

His father, he’d claim, worked for notorious Chicago gangsters The Jones Boys, and Jones himself would run errands for local pimps. “It was fun,” he told The Guardian in 2014. But finding a self-made emancipation in jazz music, having introduced himself to a 16-year-old Ray Charles at the age of 14 and earning a scholarship to Boston’s Berklee College of Music in 1951, made Jones both proud and assured of his achievements – and keen to support others not so fortunate. “The rich aren’t doing enough,” he told Vulture. “They don’t f***ing care. I came from the street, and I care about these kids who don’t have enough because I feel I’m one of ’em.”

Hence Jones’s 50 years of humanitarian and social activism work. In the Sixties, he was a loud supporter of Martin Luther King Jr and founded the Institute for Black American Music and Chicago’s Black Arts Festival to help record and celebrate the fundamental contribution of African American artists to western music. He would go on to work closely with “my little brother” Bono on numerous philanthropic causes at the highest levels of entertainment and politics. “I introduced him to all the heads of state in the world that I know, and he did the same for me,” he told The Guardian.

In the Seventies, he launched Quincy Jones workshops to support talented inner-city youth in Los Angeles and was crucial in discovering then-aspiring actor Will Smith when his Quincy Jones Productions company created The Fresh Prince of Bel Air in 1990. More than anything, he will likely be best remembered for helping turn Michael Jackson from child performer into the world’s biggest pop star. They had reconnected when both were working on The Wiz, Sidney Lumet’s 1978 remake of The Wizard of Oz; Jackson was just 12 years old. According to Jones, the Jackson 5 star told him he was looking for someone to produce his first solo outing.

Fusing funk pop and disco, and channelling the sound towards a more sophisticated electronic future, the first album they made together, 1979’s Off the Wall, sold 20 million copies; the second, Thriller, north of 65 million. For that alone, Jones will forever stand as one of the major architects of modern pop.

The slickness, easy funk groove and melodic immediacy of Jones’s work with Jackson, though, was the culmination of decades of acclaimed music-making that shouldn’t be overshadowed. During his early career, he played trumpet on Elvis Presley’s debut TV appearance, toured as musical director for Dizzy Gillespie, and fronted his own celebrated big band. He also produced and arranged acts including Sammy Davis Jr, Peggy Lee, Sarah Vaughan and Sinatra, whose “Fly Me to the Moon” would become the first song played on the lunar surface.

Time named him one of the most influential jazz musicians of the 20th century. Between his first album, 1995’s Jazz Abroad, to his last, 2010’s Q Soul Bossa Nostra, Jones evolved from renowned player to masterful conductor and arranger, moving with the times through funk, disco and pop – and gathering a vast array of acolytes along the way.

The guest lists on his last few albums are a virtual Who’s Who of pop, jazz, rap and R&B: Bono, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, Queen Latifah, Phil Collins, LL Cool J, Snoop Dogg, Akon, John Legend, Amy Winehouse and dozens more turn out to be brushed by his legend. After almost seven decades of against-the-odds success, entrepreneurship and humanitarianism, the most definitive message Jones leaves us was perhaps one of his simplest. Don’t stop ’til you get enough.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments