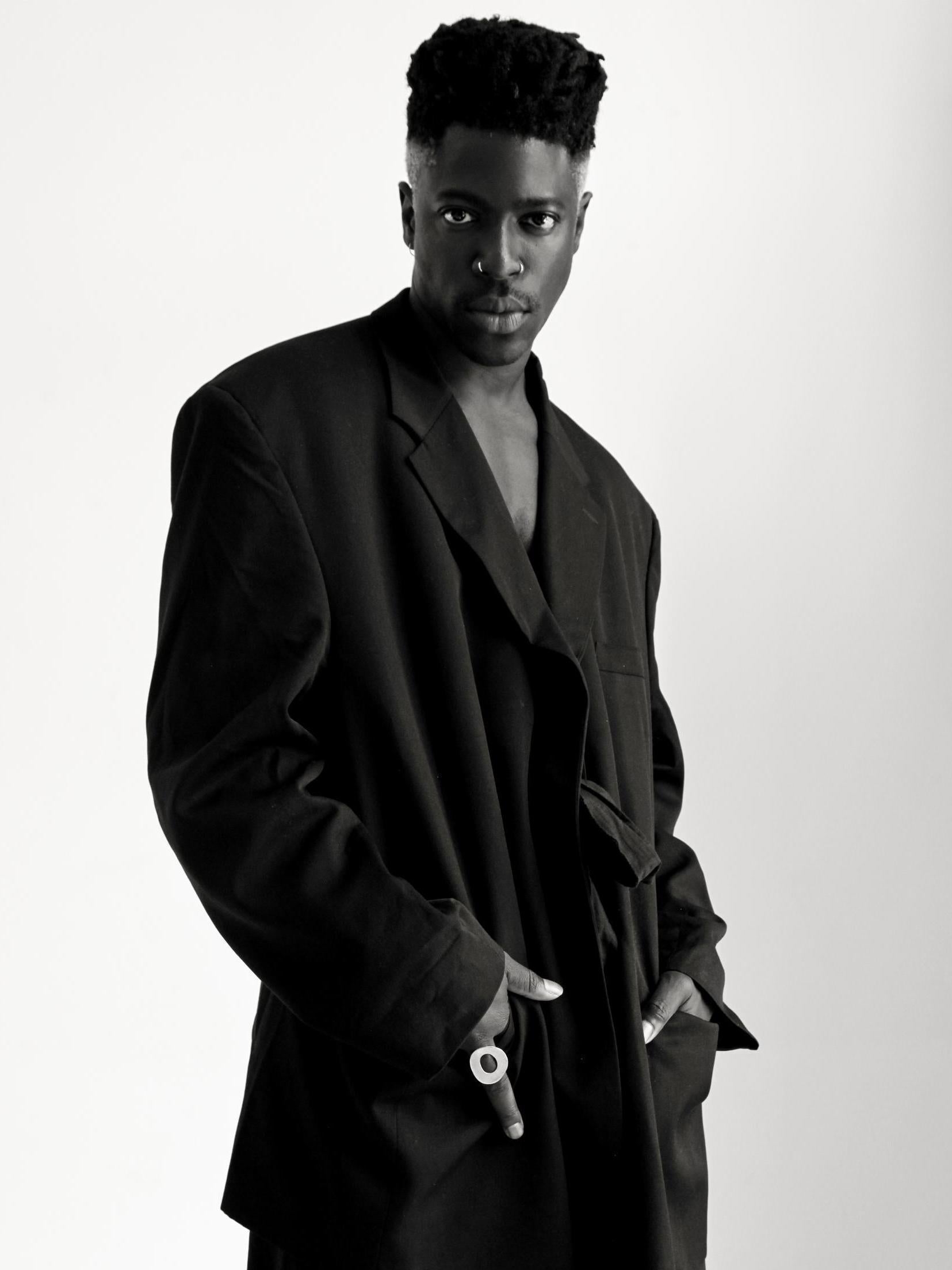

Moses Sumney: ‘Men are entitled to find what socially responsible worth they have’

The musician has made one of the albums of the year in ‘Græ’, with its bold exploration of gender binaries, sexuality and identity. It’s time masculinity had a makeover, he tells Helen Brown

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mas-cul-inity… Hmmmm…” Moses Sumney rolls the word slowly and uncertainly around his mouth like a man at a wine tasting. He savours each syllable, but with an audible inclination to spit. The 28-year-old Ghanaian-American feels that there is still “a lot to be discovered” about that topic. “Pop culture has swung the pendulum really hard against the patriarchy in a way that forgets that inherent masculinity – outside of the toxic sphere – isn’t necessarily negative,” he says. “We need to look again for the positives.”

The question of how to be a man in 2020 is explored with bold and beautiful nuance throughout Sumney’s second album, Græ. One accompanying video – for the gentle, acoustic “Polly” – finds him staring straight to camera, tears streaming relentlessly down his face as he asks a polyamorous lover: “Am I just your Friday dick?” Another – for the pugnacious “Virile” – finds him stripped to the waist, flexing muscles it took him a year to build, dancing between dangling hunks of meat and sneering: “Cheers to the patriarchs… you got the wrong idea, son.” The song and its visuals “represent what it feels like to be a black man in America,” he says. His daring, experimental and sexually charged but sexually ambivalent tone makes him sound like a bit of a millennial Bowie, slipping defiantly beyond the conventional pigeonholes of identification.

Although Sumney was courted by all the major labels the minute he broke through in 2014, quickly drawing praise from Beck (with whom he collaborated), Sufjan Stevens and Solange Knowles, he made a wise choice to “go weirder” by signing with Jagjaguwar. The indie label – also home to Bon Iver, Angel Olsen and Unknown Mortal Orchestra – has given him greater freedom of expression, with a genre-defying sound that cocoons his gorgeous falsetto in silken layers of harp, electric guitar, lute, synth and spoken word interludes. If he had to define it, he’d say he made “experimental folk-soul-jazz”, although, as with most things, he’d rather not define it at all.

Sumney’s immediate musical allure lies in his sweet, soulful crackle-croon, so it takes me a while to adjust to the ridiculously deep, Barry White rumble of his speaking voice when I call him at his home in Asheville, North Carolina, where he is locked down and “recuperating” from making Græ with lots of books and box sets. While he says the album was “fun” to make, he was also drained because he does almost all aspects of the work himself. In addition to writing and arranging everything, he directed his own videos, so it’s unsurprising that he is welcoming the down time. As we make a little quarantine small talk, I say it’s a bit spooky how Græ opens with the track “Insula”, which plays with the pandemic buzzword “isolation”, and he laughs. “Well, Moses was a prophet…”

Sumney, the son of a preacher, was named in all earnestness after the biblical bearer of the Ten Commandments. His parents, both Christian pastors from Ghana, moved to San Bernardino, 60 miles east of Los Angeles, where Sumney was born in 1991. They were technically illegal immigrants – on new song “Cut Me” he sings “guess I’m a true immigrant’s son” – although now Sumney says he prefers the term “alternative entrants”. Despite their strict faith, even banning their children’s “demonic” Pokémon cards, on one occasion, they brought radical pan-Africanism into their belief system.

When Sumney was 10, they moved their family back to the Ghanian capital of Accra for six years. Their son – once teased for being the African in America – was disoriented to now find himself equally mocked for being the American in Africa. “In Accra,” he explains, “people are very chilled, very fun. They have a laugh and a dance. As a very shy and reserved child, I hated it. The culture did not gel with me then, although I enjoy it now.” He also found it hard to catch it up at school, despite being smart. “I did not understand anything,” he says, and so “I went to the bottom of the class. Then when I came back to America and went to UCLA, I was an honours student. I feel like I grew up on every side of every coin.”

The constant perspective-flipping of his childhood meant he never felt he belonged. And although he now enjoys how that gives him “the liberating ability not to fit in anywhere I like, including North Carolina”, it’s a freedom that comes after years of struggle. He credits his friend Taiye Selasi, the author who provides Græ’s narrative interludes, with helping him see that “when you move between cultures you don’t belong to one thing or the other. She says you become a third thing. There’s a kind of splitting into something nameless and shapeless...” He adds that “being a middle child and having undiagnosed ADHD” didn’t make him any more comfortable with his identity. “But having a creative imagination made going off into my own head not just bearable but fun. There was always so much going on in my head. It could be overwhelming.”

That multiplicity extends to Sumney’s musical approach, too: “I realise that the way I combine genre comes from the combined genre of my childhood,” he says. He did, however, find solace in pop music. In Ghana, Sumney compensated for a lack of friends with a romantic obsession with American pop music. He learned to sing along with Nelly Furtado “rewinding, rewinding, rewinding, over and over. Then I started to record my voice, and that became a repeating thing.” On hitting puberty he became “terrified of my voice dropping. Falsetto had become a safe, comfortable zone for me. So I continued to sing that way all the time. I first heard Ella Fitzgerald at 16 and had to learn to do riffs. I would transcribe and replicate all her scats – that felt so good.”

Although he jokes that he now “sounds like Macy Gray smoked too many cigarettes”, he’s aware his voice has the power “to bring you in with beauty. I can sing in a way that pop music prioritises: all those high notes and riffs. But then I want to surprise you with production that’s heady and complicated, a little uncomfortable. Or with lyrics that are deeply sad or melancholic. I want to combine the things that attract you with the things that repulse you. I need to sound ugly sometimes, too.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Sumney’s 2017 serene debut, Aromanticism, stirred together all that swooning intensity and social disconnection. Its concept was challenging. He told The New York Times that he had “never been in love, in romantic love” and never connected with love songs. He had wanted to write music that “questions the idea that romantic love is the be all and end all of human existence” and wrote lines like “Am I still vital/ If my heart is idle?”. Many critics loved the way he left so much open and unanswered.

But today he admits that, despite that supposed openness, he became uncomfortable with the way “I boxed myself into a corner with Aromanticism. I got categorised as somebody who hates love, which is not something I ever said. And it wasn’t something fully that journalists ever said, although the idea was exaggerated in interviews.”

While he doesn’t want to discuss his romantic status, he is happy to expound on the public ideas about it. He is often billed as a “queer” musician, although I can’t find any interviews in which he has defined himself that way. “I have never identified, publicly or privately, as queer,” he says. “But I don’t correct people when they say that. I try not to correct people too much these days, because the desire to do so stems from ego. And I realised at some point that proclamations of identification are largely for other people, not for the self. So people can call me whatever they want to call me, if it helps them feel actualised or like they are relating to something they see in themselves. But it’s worth noting that no one has ever been considerate enough to ask me.”

Millennials, he continues, are “more open about sexuality, less ashamed, more open to acknowledging the spectrum” than their parents. “But they are not nearly as free as the next generation, who are thankfully marching toward a new kind of liberation.”

After graduating from UCLA, Sumney worked, briefly, as a music journalist and knows how the online narratives seek to pigeonhole artists. “I started to think about how the internet is binaristic. People just read the headline. Interviews just give you one angle. Considering that made me challenge myself with the nearly impossible task of talking about multiplicity. Beyond that, talking about greyness. Exploring subtlety, uncertainty, blandness, nothing flashy…” No clickbait? “Exactly!”

This makes him a slippery interviewee. Sumney prefers asking questions to giving answers. Græ – released in two parts, which flow seamlessly together – is a sonic adventure of Björkian heights. While he says Aromanticism was “meditative”, with its questions directed more inwardly by the strings of an acoustic guitar, Græ is more surprising, its questions designed to buttonhole passersby. “People have come to associate my singing with prettiness,” says Sumney, and so he “loved creating the stuttering, guttural AA-AA-AA sound that opens ‘Virile’”, a huge track that backs delicate harp and lute strings with clanging industrial percussion and metallic guitars.

He’s resistant to direct readings of his lyrics because, he says, it degrades human complexity. He’s often sexually direct, singing of a desire to “melt like cotton candy” in the mouths of many lovers on “Polly”, a song that could be interpreted as a polyamarous person singing to a monogamous lover. But when I ask if another line is about fisting, he deflects. “It says more about the listener if they think it’s about fisting! I just wanna be an honest lyricist and sometimes you can’t talk about intimacy without addressing the flesh.”

When it comes to masculinity, he says, coming back to the record’s central preoccupation, he needed to “embody it” in order to properly critique it, hence turbo-buffing up for the “Virile” video. He found it gruelling to give up sugar on a year’s keto diet (though “all bets are off” in quarantine) but also exciting to develop the kind of mighty physique worshipped by a patriarchal culture that doesn’t make much room for men who study poetry and cover themselves in glitter. The video was about representing a person caught between the “two extremes”, he says; “a person breaking free from the body and also representing the black, male body as an object for consumption”.

He feels that this is an interesting moment for masculinity, post-MeToo, but we’ve still got a long way to go. “Men should look on this moment as an opportunity, not a threat,” he says. “Beyond the oppression, beyond the idea that value came from ruling over others” – which, he adds, he doesn’t connect with – “men are entitled to find what socially responsible worth they have.” In his case, he loves “my stature, my strength and resilience, and my desire to nurture others” – there’s a lot more scope for the still-limited interpretation of masculinity that we have today. “I hope I bring some of that to the conversation,” says Sumney. “That’s all I can hope for. If I do that, I’m happy.”

Græ is out on 15 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments