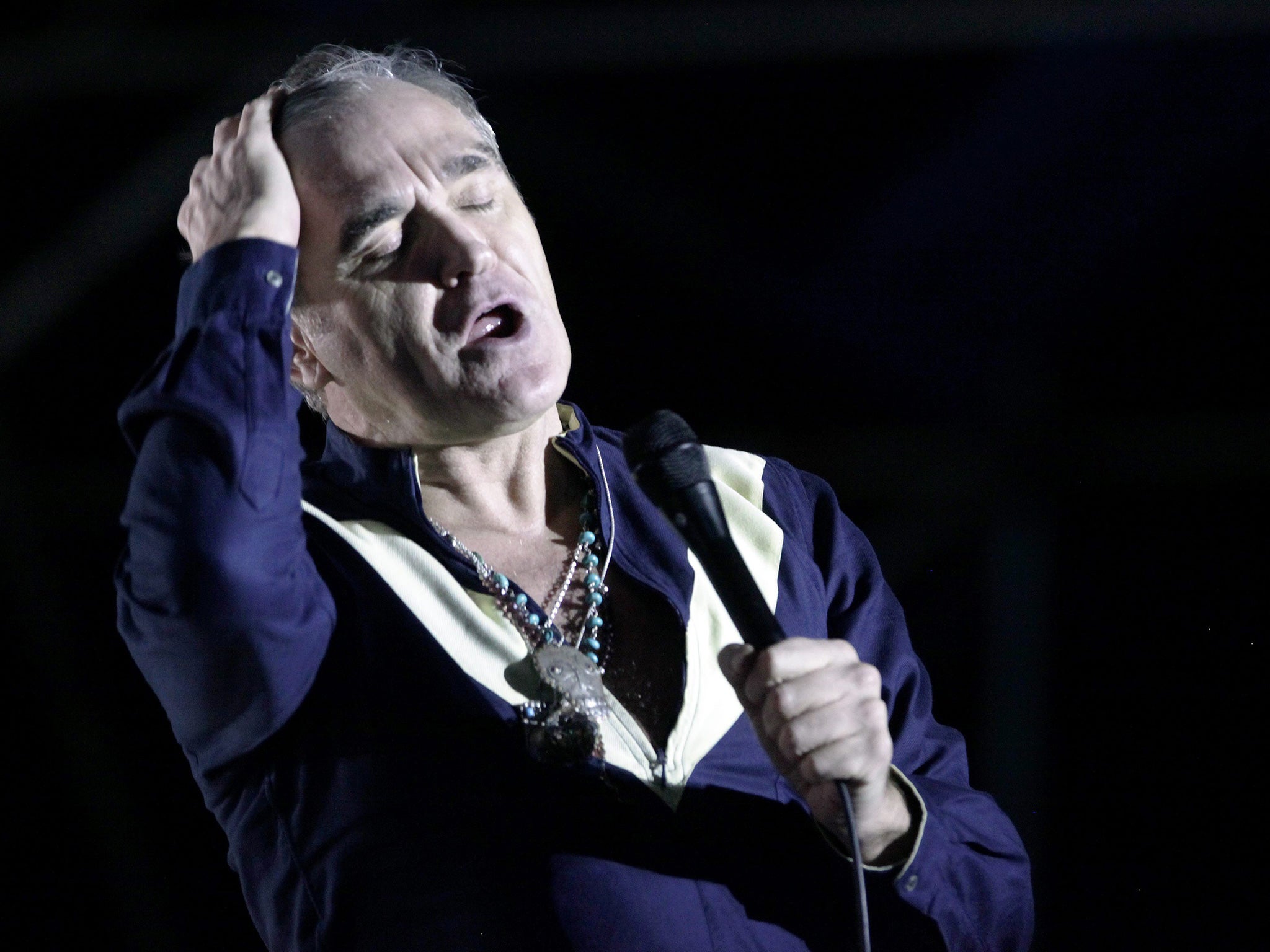

This Charmless Man: How Morrissey’s big mouth struck again... and again

When bigmouth strikes these days, it can be hard to stomach. Nick Hasted details the decline of a once-beautiful artist, who now seems to expect and almost cultivate betrayal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Listening to Morrissey is like a drawn-out divorce; you keep seeing hopeful flickers of the old love, but you know something’s broken for good. The traditional rites were replayed across London venues last week, as devoted fans rushed to touch the one star who still casts a spell like Ziggy Stardust’s rock’n’roll suicide, or the primal teenage princes of an old Nik Cohn profile.

More recent Morrissey rituals have gone with it as he’s made his way across the UK, loathing Nicola Sturgeon and loving Brexit. The “mainstream media” – decried on his new song “My Love I’d Do Anything for You” – had their headlines written for them, and a few more old fans quietly left the room.

The Steven Morrissey who in his youth shared a TV studio with Bernard Manning in visceral, mutual horror now calls Nigel Farage a “liberal educator”. But his ugly views aren’t really the problem. It’s his calcified music that’s irredeemable. His latest album, Low in High School, has bright moments, but holds little hope that we’ll see his best once more.

When bigmouth strikes again these days, it can admittedly be hard to stomach. His vegetarianism encourages misanthropy more than empathy, as when he dubbed the Chinese a “subspecies” for their treatment of animals in 2010. Telling Der Spiegel in 2017 that refugees had made Germany “the rape capital of Europe”, meanwhile, seems to show that the troubling attitudes that NME first accused him of in 1992 have developed unchecked.

The expansive, attractive sense of Englishness that orbited The Smiths with icons from Charles Hawtrey to Keats soured early anyway. In the same 1992 Q interview in which Morrissey declared that he didn’t think “that white and black people will ever really get on and like each other”, he said: “I don’t want to be European. I want England to remain an island.”

There remains an upside to his outspokenness. The “lock-jawed pop stars” afraid to “smear their lovely career”, who he condemned in “The World Is Full of Crashing Bores”, are with us more than ever. The front ranks of what’s left of British alternative rock, too, mostly come from comfortable backgrounds very unlike Morrissey or Johnny Marr’s, and rarely seem troubled by iniquity. The vast good done by “politically correct” speech and #MeToo, meanwhile, has also led to obsessive policing of acceptable discourse, narrowed further by social media firestorms.

The internet doesn’t intrude on Morrissey and, as he sang on last year’s single “Spent the Day in Bed”, his dreams at least remain “legal”, and his thoughts his own. Low in High School therefore bulges with messy opinions on the Arab Spring (as he sensitively, sensually bonds with a protestor on “In Your Lap”) and Israel.

His blanket condemnation of soldiers and their work in “I Bury the Living” and “I Wish You Lonely”, with the latter seeming to gloat at their deaths, is cruel. It’s no worse, though, than our patriotic acceptance of the civilian deaths caused by our military. The Morrissey whose most controversial ’90s song, “The National Front Disco”, was sung in sorrow for a boy clinging, lost, to racism, is still worth listening to.

Morrissey can still be glimpsed at his best, then, right next to him at his worst. Listen back to The Smiths, though, and his decline is defined. On The Queen is Dead alone, the 1986 album I left my last day of school clutching, “Never Had No One Ever”, “There is a Light that Never Goes Out” and “I Know it’s Over” showed their singer sunk fathoms-deep in suffocated desire, straitjacketed in his own body, and gloriously breaking free in his mind.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Intertwined with the liberating glow of Johnny Marr’s music, Smiths songs reached out to the listener in a mutual ache for love. Something equally profound might have followed, as Leonard Cohen, say, spent a lifetime working towards happiness. Solo Morrissey instead shrank into lovelessness.

His Autobiography (2013) charts the landmarks in this personal and artistic tragedy. It begins with a richly recalled evocation of his Manchester childhood, where he walked on “flagstones that have cracked under the duress like the people who tread them”. It’s a sooty, crepuscular, condemned world, left behind by everything outside it, in which communities and families are ripped asunder by alien authorities. His sense of injustice at all those in power starts here.

The kitchen-sink cinema icons on Smiths record sleeves immortalised a black-and-white environment that he remembers living in. Morrissey writes about his relatives with devoted love. Though he could be an outsider in it, this working-class community was home. His 2006 song “On the Streets I Ran” goes back to it, but it’s gone. 2017’s “Home is a Question Mark” wonders where.

Life in the eternal sunshine of the anti-Manchester, LA, briefly buoys him. But Autobiography ends in the only other place he’s ever belonged: the stage. He lists audiences in precise numbers, as if trying to keep his seat in Parliament, and sociologically, as if to prove his relevance. Their fashion sense, tribalism and eruptions of violent emotion fuel him. Though he rails against religion at every opportunity, devotion pumps his blood. His new song, “Jacky’s Only Happy When She’s Up on the Stage”, couldn’t be more autobiographical. His fans are his community. So long as they believe in him, the rest can go to hell.

The boy who admired his parents and befriended Johnny Marr as an equal never grew up any further. The spontaneous afternoon that Marr’s autobiography records the pair spending in a Manchester pub in September 2008 is even more poignant than The Smiths reunion they flirted with then. Who else can Morrissey talk naturally with now?

Instead, Autobiography and his recent records seem to relish the suspicious walls he’s built around himself. From record companies to friends, he expects and almost cultivates betrayal. The shifting members of his band are among the few to provide companionship. The mostly decreasing circles of his music are the product of a world of one.

In song after song, in Autobiography and his perverse novel List of the Lost (2015), Morrissey sees humanity as a fearful, painful, mostly loathsome thing. His loneliness once made him beautiful. Now, as he pulls up the drawbridge on refugees and the rest of us, it leaves less of him every day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments