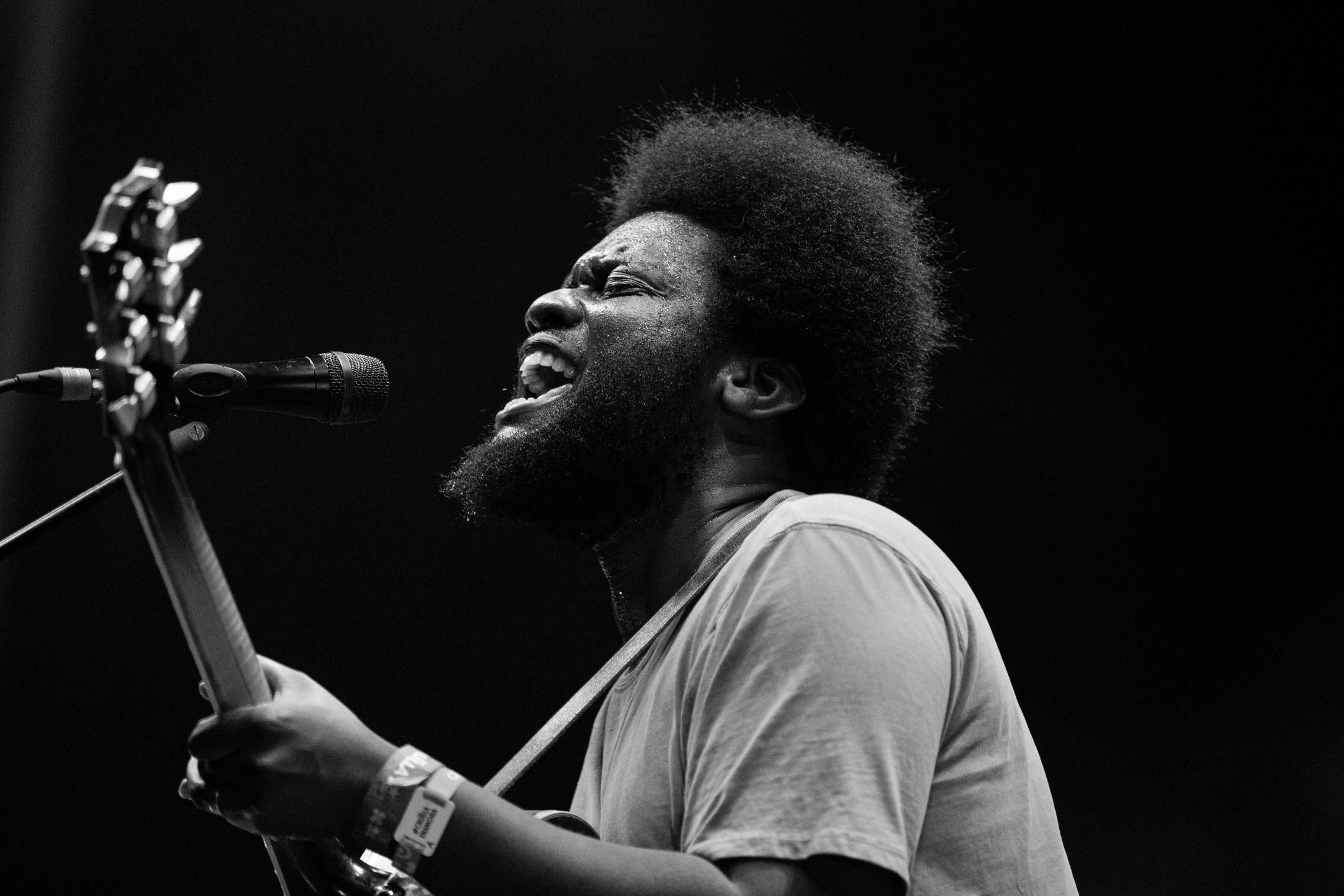

Michael Kiwanuka: ‘Sometimes you’ve got to be vulnerable – even if it’s not easy’

As he prepares to release his brilliant third album, the Mercury Prize-shortlisted artist speaks with Roisin O'Connor about moving to Southampton, racism in the UK, and coming to terms with his identity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Kiwanuka’s house is falling down. Or rather, the wall of his front garden is. The 32-year-old artist recently moved from his long-time home in Muswell Hill, north London, to Southampton. He’s loving every minute of the carnage it’s unleashed – to the point that he and his wife, Charlotte, have decided to bring a puppy, called Whisky, into the chaos.

“He’s going through his ‘teenage phase’,” Kiwanuka says. “He’s amazing, but I’m always travelling, so Charlotte has to deal with him.” He lived around Kentish Town and Camden before he met his wife, and was out every night. “I don’t regret that,” he says, “but you get to a stage when you want to settle down. And I’m lucky that I’m at a stage in my career where I don’t need to hustle so much.”

He’s sitting in a nondescript cafe in Aldgate, sipping a coffee while a man in a suit has a noisy phone conversation behind us. Kiwanuka, who is dressed casually in a wool check shirt, doesn’t seem to notice: he’s talking happily about his third record, the self-titled Kiwanuka. And you can’t blame him – it’s a fantastic album, Kiwanuka’s best by a mile, even after 2012’s debut Home Again, and the critically adored Love & Hate (2016), both of which were shortlisted for the Mercury Prize.

A quieter existence seems to suit him. He’s a calming presence to be around, with huge soulful eyes and a relaxed demeanour that he took into the studio. Kiwanuka relies far more on instinct than any of his previous work: it opens on the jangling, Kamasi Washington-esque “You Ain’t the Problem”, a defiant track borne of Kiwanuka’s feelings of inferiority in an industry that is at once highly competitive and quick to celebrate mediocrity over genuine talent. More than one article has posed the question as to why Kiwanuka isn’t more successful than he is. More often than not, the conclusion is: his peers are white, he is not.

“I think it’s slowly changing, but if you think about the artists that break through...” He trails off. “That’s why I’ve become so obsessed with identity. The way people listen to artists, including myself, is also with your eyes.” At school, Kiwanuka’s friends were white and middle-class, and most of them had musical instruments bought for them by their parents. Kiwanuka was impressed by the ones who could play guitar, and persuaded his parents – who fled Uganda during Idi Amin’s murderous regime in the Seventies – to let him pursue a career in music on the condition he studied at university (he attended the Royal Academy of Music but later dropped out).

“The guitar didn’t used to be seen as an instrument for posh people,” he says. “And it’s ingrained in us to relate to someone who looks like we do.” When he was at school, everyone on MTV who looked like him was a rapper, or singing Nineties R&B: “But then I’d find these old Seventies records, and see people like Jimi Hendrix or Bill Withers, wearing flared jeans and playing guitars.”

He has ideas of starting a studio in Southampton; his wife is a musician as well, and sang on tracks that didn’t quite make the final album (he says she didn’t mind, but was a “bit gutted” himself). “She’s got a ridiculously good voice that I want people to hear,“ he says. More than anything, he sounds determined to provide a space for local youth: “There are so many young people in Southampton, and you think that kids in London don’t have anything to do – imagine what it’s like there.” He wants to start a gallery, too: “We have all these crazy dreams, and being in Southampton is like a blank canvas.”

Some might find it strange that Kiwanuka would title his third album after himself, where most artists do so for their debut. But it’s a statement of identity by an artist who, until recently, felt caught between the middle-class surroundings of his childhood and the culture of his parents. Even the pronunciation of his name has been anglicised, he says: in Kampala (Uganda’s capital), it’s Chi-wa-nuka.

“The reason you get disconnected from your heritage and lineage is when it seems alien to what’s around you, and you just want to fit in,” he says, reflecting on the “pervasive” racism he senses in the UK. “It’s difficult to describe – it’s just subtler. People compartmentalise, they fixate on people from certain backgrounds.” He wants to see more people from different backgrounds and ethnicities in positions of power: “I think that’s when you see the perception of other races change.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

He applies this to his own audience, of which the make-up is almost entirely white. It threw him when he went to America for the first time, and it’s something he still thinks about now – to the point he and his band were discussing it in the studio.

“I was like, what is that?” he says. “Because everyone making my music is black.” He thinks it could be a while before “the penny drops” and his audience becomes more diverse. Circling back to how his schoolfriends all had their own instruments at home, he wonders if non-white fans are put off by the extravagant production and instrumentation of his own music: “It’s expensive music to make,” he says. “If you’re a rapper you can do it on a laptop and a mic. It’s accessible – fans think, ‘I could do that.’”

“This is kind of controversial,” he shrugs, “but I think when you come from oppression, for your skin colour, your sex... often you’ve been beaten down so much that you do it to each other. You get so used to being low down that when you see someone rise above you, you want to drag them back down.”

In many ways, Kiwanuka is a political album, one that samples civil-rights leaders such as John Lewis. The track “Hero” is inspired by activist Fred Hampton, the 21-year-old leader of the Black Panthers’ Illinois chapter who was murdered by police in 1969. But the album is not so much a call to arms as a series of quiet yet profound observations; it reminds you of the work of war poet Wilfred Owen, and other artists who felt compelled to document times of conflict.

“All of these people have a way of speaking so powerfully,” Kiwanuka says, citing the environmental activist Greta Thunberg as a present-day example. “She’s so young! People assume young people are disengaged, that they’re just playing Fortnite, but it’s the opposite.” There’s a lyric in his song “Light”, he brings up: “The young and dumb will always need one of their own to lead.”

The record is influenced by as broad a palette as The Rolling Stones, Gil Scott-Heron and Marvin Gaye, to the relatively unknown A$AP Rocky collaborator Joe Fox, who is recalled on the acoustic, reverb-drenched track “Hero”. There’s a real alchemy, too, when Kiwanuka gets together with Grammy award-winning producer Danger Mouse (The Black Keys, Gorillaz, Beck, A$AP Rocky, Adele) and the London-based Inflo, who worked with Little Simz on her 2019 masterpiece GREY Area. Both producers, says Kiwanuka, have a deep understanding of his aversion to being pigeonholed. “There aren’t many young black producers who do this kind of music, so Inflo’s fighting for that. We definitely met at the right time.”

He also credits Inflo with his increased willingness to appear in his own music videos, having previously felt self-conscious about his image. Fans will have seen him recently in the visuals for “You Ain’t the Problem”, cameoing with Ed Sheeran in Danny Boyle’s film Yesterday, and with south London producer-musician wunderkind Tom Misch, in the video for their buoyant, funk-influenced track “Money”. Neither Kiwanuka nor Misch can drive, so they ended up being towed around the California desert in a series of luxury cars.

“I was really nervous, terrified actually, of making that video,” Kiwanuka says. “But I think it’s a good sign, because it means you’re pushing yourself.” He recalls Inflo telling him how important it is for fans to see the artist they’re listening to: “It helps them connect.”

As our interview comes to an end, I mention how this seems like a radical step-up for an artist who, while never accused of playing it safe, has equally never been hailed for breaking new ground. “It’s definitely a big move for me,” he says of the album, “but I think it was the right time. You get to an age, particularly first-generation black men, where you redefine or reacquaint yourself with your background, and I think that’s been affecting art as well. Sometimes you’ve got to be vulnerable – even if it’s not easy.”

Kiwanuka is out on 1 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments