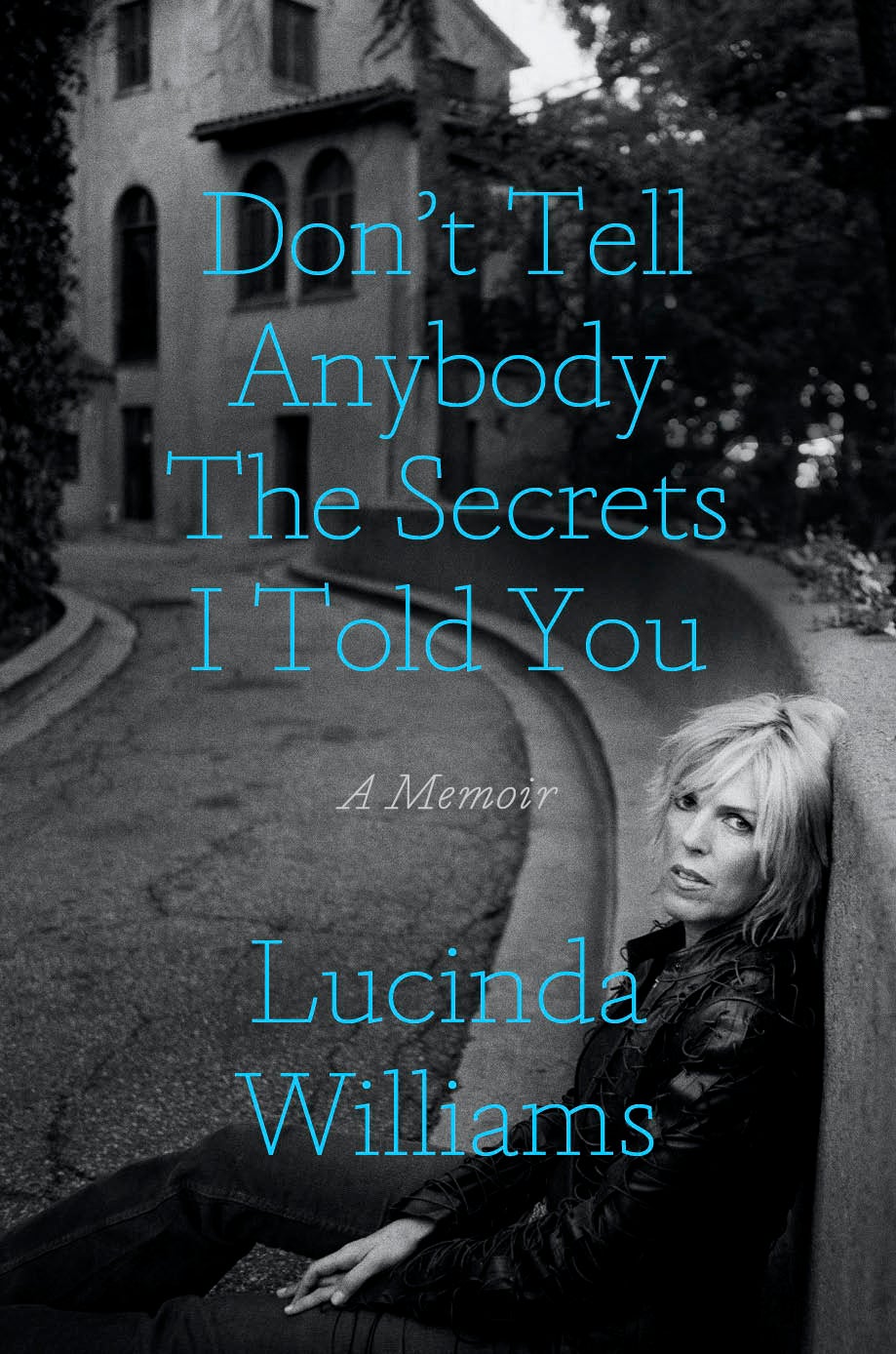

‘That was one of the things I was going to take out!’: Lucinda Williams on her soul-baring memoir

The singer-songwriter has written a deeply personal memoir, ‘Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You’. She talks to Jim Farber about revisiting controversial family history, her early struggles in a male-dominated music industry and wanting to be ‘a friend’ to Ryan Adams

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lucinda Williams has been having a lot of second thoughts lately. This week, the singer’s memoir, Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You, will be published. Ask her about important parts of it, though, and her reactions range from trepidation to borderline shame. Early in the book, she writes about suffering from OCD, which she began to experience as a young teen when the obsession caused her to pick at her skin so badly it looked like she had cut herself. “Oh God, that’s so embarrassing,” Williams says with a wince when the subject is brought up. “Because of the deadline on the book, I didn’t have time to go back and amend things. That was one of the things I was going to take out!”

Another concerns a story her father told her about her mother being sexually molested by various members of her family when she was a child. “I knew that was going to open up a mountain of questions, so I was going to leave that out, too,” she admits. “The key word here is ‘alleged.’ We don’t know what happened to her for sure. It was second-hand information from my father.”

In the end, that troubling anecdote, as well as others that vexed her – including mental health issues experienced by her brother that have rendered him a virtual recluse – stayed in the book, because, says Williams, “it is what it is. I wrote about things the way they were.”

That way, it seems, was, by turns, harrowing and rousing, wild and rich. While making sure to highlight the many achievements that have made Williams one of the most acclaimed artists of her generation, the book also makes clear that she isn’t exaggerating when she compares her life to the Southern Gothic fiction of Flannery O’Connor. The simple act of talking to Williams is an immersion into the culture of the American South. She has a drawl so pronounced, it sounds like she gargles with molasses before she speaks. The roots-rock legend, who broke through in the Nineties with the classic album of pain, longing and grit, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, reveals everything in the book from her family’s deepest secrets, to her struggles to be understood in the music industry, to the corrosive romances that inspired many of her songs.

Her mother, a secret alcoholic, suffered from mental illness that led to a course of electroshock therapy and a prescription to Lithium, neither of which did anything to alter her erratic behaviour. While Williams describes her mother’s good days as full of intelligent talk and loving care, her bad ones could result in her showing up in just her underwear at an important meeting or locking her daughter in a closet when she couldn’t cope with being a parent. In the book she presents her father, Miller Williams, a celebrated poet and professor, as a beacon of both emotional and creative support. At the same time, when Williams was entering adolescence, her father began a romantic relationship with a student of his who was 18 at the time – just six years older than his daughter. To make it more awkward, the student was also Williams’ babysitter. That event took place in the 1960s, a time when such things read differently than they do today. “The age thing crossed my mind when I was writing about it,” the singer says. “But, at the time, I don’t remember it even being discussed or questioned.”

That laissez-faire attitude didn’t only have to do with the era, but also with the bohemian milieu of the Williams family. “My family was always very progressive. This was just one more thing to be progressive about.”

It helped that the relationship was far from just an affair. It led to a long and happy marriage between her father and her stepmother following the divorce of Williams’ parents. When the singer writes in the book about the more disturbing aspects of her early home life, many of which involved her mother, she’s remarkably understanding and forgiving. Asked if this represents her current perspective as a mature adult of 70 who has had years of therapy, as opposed to that of the vulnerable child she was at the time, Williams allows that it may be the former. Yet, she also stresses that the way her father explained her mother’s condition to her and her siblings made a dramatic difference. “He was always very compassionate, so if my mother was having a particularly hard time, he would say ‘it’s not her fault. She’s not well,’ she says. “He would present it to us that way, so we had a place to put it in our minds. That’s why we bonded.”

They bonded, too, on their mutual devotion to the artistic life, for which her father became her ultimate role model, if sometimes an excessive one. In the book, Williams states that when it comes to drunken partying, musicians have nothing on writers. It seems that the men Williams tended to get romantically involved with for many decades in her life represented a rough mix of her father’s intellectual acuity and her mother’s emotional unavailability. Her type, she said, was “a bad boy with brains – a biker crossed with an academic”.

Often, they were members of her band, including one guy who, after their relationship became serious enough to invite talk of marriage, promptly dumped her with the line, “I love you, but you just don’t fit into my agenda right now.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Another musician she had a fling with, Paul Westerberg of The Replacements, proved equally elusive. During their affair, she writes, he kept yammering on about his issues with his kids, which prompted a fed-up Williams to finally suggest he tell his problems to a therapist rather than to her. He instantly ghosted her. She experienced similar evasiveness from Ryan Adams, with whom she had more of an emotional affair with than a fully physical one. In 2003, she chronicled the relationship in her song “Those Three Days.” In the book, Williams writes that Adams got back in touch with her in 2019 after news broke about the many accusations of sexual harassment made against him. “You must think I’m a monster,” she reports him saying to her. “No,” she answered. “I just think you made some bad choices.”

Williams demurs when I ask if she believes the allegations or not. “I don’t like to make accusations without knowing the other side of the story,” she says, adding that the cultural moment at the time also affected her decision to refrain from judgement. “There was a lot of that going on at the time – the whole MeToo thing. I saw a lot of imbalance. I felt like it was just getting out of control. I wanted to be a friend to him. The last thing he needed was one more person judging him.”

Besides, Williams had experienced years of being harshly judged herself, especially by people in the music industry. A significant portion of the book chronicles her dealings with record executives who didn’t understand her taste, character, or intent. Upon hearing her songs in the Eighties, one prominent A&R man said that they “didn’t have bridges in them, so I needed to go back to the drawing board, which was ridiculous. One of the songs he pointed to was ‘Change the Locks’,’ which was eventually recorded by Tom Petty.”

When she told another clueless A&R person that she wanted her production sound to evoke “Blonde on Blonde”, he thought that was the name of a new band, rather than the title of a Bob Dylan album commonly recognised as one of the most important releases of all time. She also endured some uncomfortable encounters in the industry. Williams alleges that when moviemaker Paul Schrader was hired to direct a video for her in 1998, he showed up drunk to their first meeting and announced, “if I weren’t so f***ed up right now I’d probably try to get inside your pants.” No video was made.

The issues Williams faced weren’t just with other people but within herself. Insecurity has plagued her since childhood. “That’s one of the things that formed in my brain for some reason,” she says. “I don’t know why… but it’s there.”

Somebody isn’t difficult to work with just because they change their mind about something

It came up strongly when she first started to achieve success. In 1994, when she was nominated for a Grammy for Best County Song for writing “Passionate Kisses”, which became a hit for Mary Chapin Carpenter, she became so self-conscious she bailed on the event. (She wound up winning the award). In 1997, when she was recording her breakthrough album, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, a New York Times writer shadowed her in the studio and wrote a story that presented her as a controlling and difficult person who couldn’t make a decision, accounting for the album’s long delay. “Emmylou Harris later told me, ‘never allow a journalist into the studio with you because they don’t understand the recording process,’” Williams tells me. “A lot of what he wrote about is just normal stuff that happens in the studio. Somebody isn’t difficult to work with just because they change their mind about something.”

She sees sexism in the characterisation. “I remember John Fogerty having an album that was just coming out and I think it had been 11 years between albums for him and it was never mentioned as a problem,” she says. “You work out the difference.”

At times, Williams hasn’t only been accused of being difficult but of being certifiably crazy. When she was about to meet the man who would later become her husband and manager, Tom Overby, a friend warned him that she is “literally insane”. The scathing characterisation cut especially deep because of Williams’ experience with her mother’s mental issues. “It p***ed me off,” she says. “It brought up all that stuff again about being misunderstood.”

Luckily, the warning had no effect on Overby, to whom she has been married for the last 14 years. Meeting him broke the pattern of bad boys in her life. “I was definitely ready,” she says, with an exhale that speaks of relief.

Williams has also been very prolific in those years, creating six studio albums. However, two years ago she suffered a major setback when she had a stroke. “I had to learn to walk again,” she explains. “I couldn’t get across a room without falling down.”

While she says she’s feeling great now, the stroke affected her ability to play guitar, so for her new album, Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart, which will be released in June, she co-wrote most of the songs for the first time – some with her husband; some with New York musician Jesse Malin. The book includes nothing about the stroke. Instead, it ends with her marriage to Overby in 2009, a key moment that certified her maturity and assurance. Both were long in coming. By the time Williams found a solid marriage, she was in her fifties; by the time she broke through commercially, she was in her forties. And yet neither were a concern for her because she grew up in a family free of ageism. “With us, it just wasn’t an issue,” she shrugs.

That’s a refreshing contrast to a life that has seen no shortage of dark issues. Still, the way Williams has processed them for the book displays an uncommonly non-judgmental nature, a stance that mirrors the empathy in her writing. For her, the ability to accept the mysterious nature of other people’s lives is a core value. Several times during our interview she quotes a line from a poem her father wrote titled “Compassion”. “The last line of the poem is, ‘you don’t know what wars are going on down there, where the spirit meets the bone,’” she says. “That, to me, says it all.”

‘Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You: A Memoir’ is out now. Lucinda Williams is playing Black Deer Festival 2023, 16-18 June, tickets available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments