The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

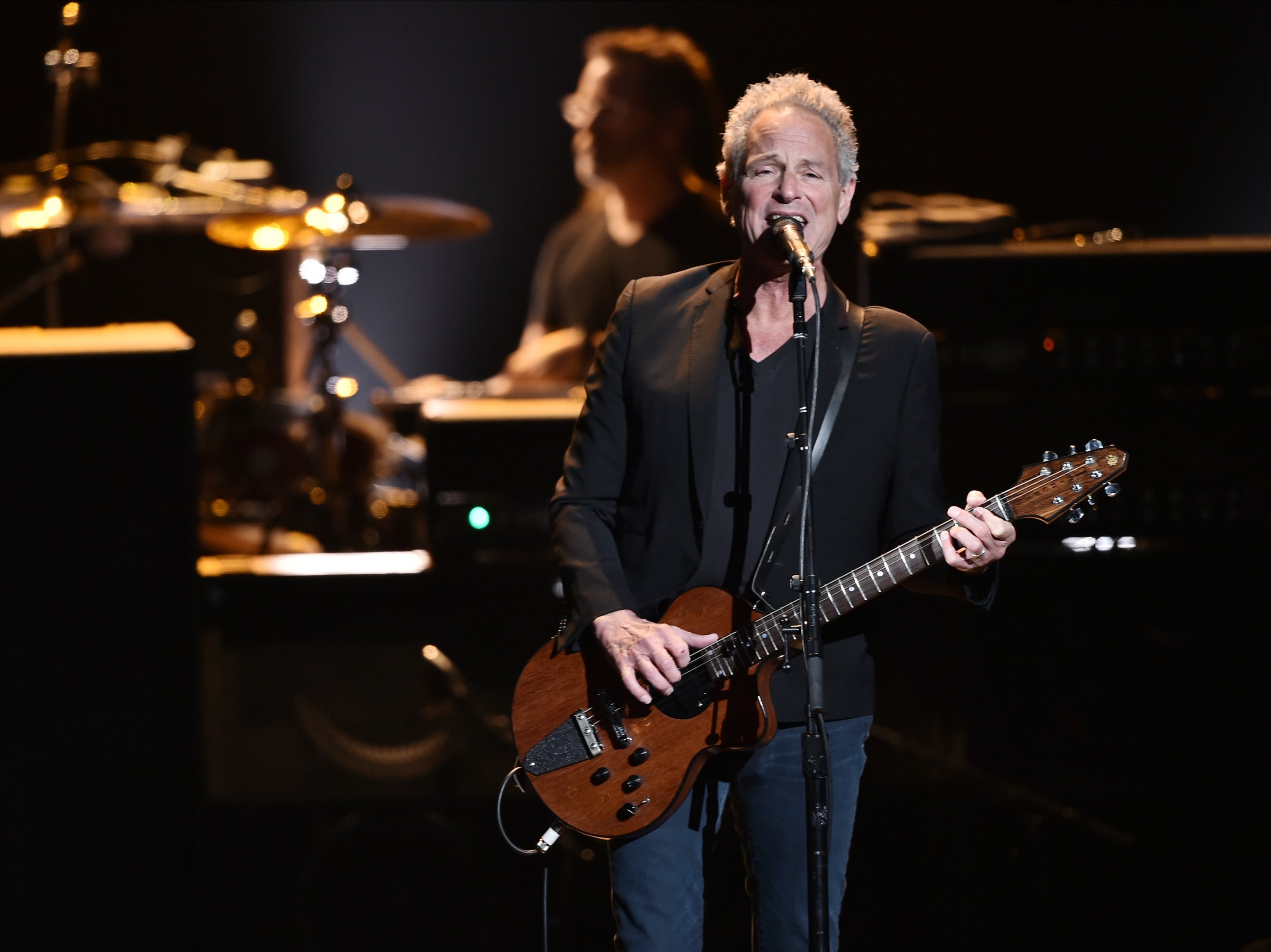

Lindsey Buckingham: ‘I think there’s a better way for Fleetwood Mac to finish up than we did’

Now that the ex-Fleetwood Mac front man’s long-awaited solo album is finished and audiences are ready to go, Buckingham is eager to get back on the road, writes Lindsay Zoladz

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One day in early February 2019, Lindsey Buckingham woke up to a wallop of a surprise: He had just had a heart attack, followed by an emergency triple bypass.

The good news was that he’d had a cardiac event at arguably the best possible time and place, while under anaesthesia for a minor medical procedure. (His older brother Greg, an Olympic swimmer, dropped dead from one alone in his backyard in 1990, at 45. A similar fate befell their father at 56.)

Buckingham found out the bad news when he tried to speak and realised he couldn’t raise his voice above a hoarse whisper: Someone had been “a little rough with the breathing tube,” as he put it, and damaged his vocal cords – not just any vocal cords, but those of the onetime Fleetwood Mac yelper responsible for such modern pop standards as “Go Your Own Way”, “Second Hand News” and “Never Going Back Again”. For months, he wasn’t sure if the injury was temporary or permanent. But fortunately, from his serene California living room one Summer Saturday afternoon, Buckingham can now recall it all with a full-voiced laugh.

“Somebody in the hospital was going, ‘Oops! Hope he doesn’t find me!’”

Buckingham, 71, may be playing a bit on what he knows is his prickly, self-serious reputation – as parodied, however absurdly, by Bill Hader on US comedy institution “Saturday Night Live” – but throughout a series of conversations he was remarkably open and quick with the occasional self-deprecating joke. As he prepares to release Lindsey Buckingham, his first solo album in a decade, on 17 September, his edges seem to have smoothed a bit in the wake of a series of perspective-shifting events: the bypass and then the pandemic, of course, but also the July 2020 death of Fleetwood Mac founder Peter Green, and Buckingham’s recent separation from Kristen Messner, his wife of 21 years and the mother of his three children.

Then there was the business, three years ago, when he got kicked out of Fleetwood Mac a beloved group known as much for its timeless songcraft as its intra-band pyrotechnics and power struggles – and then sued his former bandmates.

Many of Buckingham’s solo releases have been pressure valves for when Fleetwood Mac was feeling a little too tense or controlled. After steering the group more left of centre with the edgy and eclectic Tusk in 1979, the drummer and (in Buckingham’s words) “vibe master” Mick Fleetwood said they would have to reorient in a more commercial direction. Buckingham told him, “OK, well, I guess I’ve got to make some solo albums.”

Buckingham was able to release his first two – the taut Law and Order (1981) and the angular Go Insane (1984) – while still in the band, but after recording Fleetwood Mac’s 1987 blockbuster Tango in the Night, he took a decade-long leave to fulfil himself personally and artistically. (Buckingham’s decision to step away from an environment of excessive drug use and drinking was also, as he put it, “for my own survival”.) He made one of his best albums, Out of the Cradle (1992), and met Messner when she photographed him for another solo project. He returned to the Mac in 1997 for their triumphant Clinton-era victory lap, The Dance.

“That guy is one of the best producers on the planet,” says Rob Cavallo, a record industry executive and Grammy-winning producer who’s worked on and off with Buckingham since the mid-1990s. “So much of the style and techniques from Rumours on, so much of it is him,” he adds, referring to one of the most successful and storied albums of all time.

It’s unlikely that any single incident was to blame for Buckingham’s departure, but several days later, he was shocked to receive a call from the band’s manager, Irving Azoff, telling him he’d been fired.

Lindsey Buckingham, a blend of California-sunny power-pop and partly cloudy ballads, is perhaps the most straightforward release of his solo career. “I went into it thinking I wanted to make a pop album,” says Buckingham. While he noted that its musical reference points date back to Rumours, the subject matter is “family and long-term relationships”. Though he wrote and recorded the album in 2018, long before Messner filed for divorce, he now believes some of the stormiest songs were “a little bit prescient”.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Still, these songs aren’t all emotional turbulence: Buckingham sees them as being about how “joy and pain have to coexist side by side”. Perhaps that, too, is prescient: after a period of separation, he and Messner are once again spending time together, even though he’s not yet sure what the future holds for their relationship.

A similar haze of uncertainty clouds the future of Fleetwood Mac. Even though Buckingham and some of his bandmates are once again on speaking terms, and he admitted he’d “be back like a shot” if they’d have him, his potential return is contingent upon one member in particular.

As he tells it, the latest tensions began simmering in 2017 when he asked to postpone a proposed Fleetwood Mac outing by three months so he could release and promote a solo album: “At least one person in the band” – his eternal ex Stevie Nicks, he clarified – “wasn’t very receptive to that.”

But things boiled over in January 2018 during what Fleetwood Mac fans now simply refer to as “the smirking incident”. At a New York concert where the band were the recipients of the Recording Academy’s annual philanthropic honour, the MusiCares Person of the Year, Nicks was said to have believed that Buckingham was making a face behind her while she gave a heartfelt acceptance speech. “I would doubt very much that I was smirking,” Buckingham says, while also pointing out that band members dancing or exchanging exaggerated glances when Nicks’ stage banter went on for a while was a “running gag” in the Mac.

After decades of cumulative personal conflict, it’s unlikely that any single incident was to blame for Buckingham’s departure, but several days later, he was shocked to receive a call from the band’s manager, Irving Azoff, telling him he’d been fired. He says that Nicks had given her bandmates an ultimatum: him or me. (The members of Fleetwood Mac declined to be interviewed for this article. In December 2018, Buckingham said that he and the band had settled his lawsuit.)

Now that his long-awaited solo album is finished, though, and audiences are (if a little tentatively) ready to rock, Buckingham is eager to get back on the road. His voice is “at 95 per cent” following the breathing tube debacle. “A couple of the songs we’ve lowered the keys a little bit, but we’ve been doing that all along anyway, the older we get,” he admitted with a laugh.

Both times we meet, Buckingham wears the exact same thing – a faded black V-neck T-shirt and slim-cut jeans – as though like a rock ’n’ roll Steve Jobs, he long ago selected an optimal outfit and cleared that much more space in his mind for what is still his central concern: music.

He and his family downsized a few years ago from a sprawling Brentwood property just down the street, but he still has the living room of a person who’s been married to an interior designer and recently sold his extensive publishing catalogue for many millions of dollars. (“There was this axiom for years and years, ‘Don’t sell your publishing’,” he says. “And I think there may still be some truth to that, but you get to a certain point in your life…”)

Tasteful coffee table books adorn the gleaming slab of marble in front of us, but the house buzzes with domestic life. In the kitchen, Buckingham’s college-age daughter LeeLee and her boyfriend are baking Australian meringues. They have brought their two dogs over, which adds to the usual trio. As Buckingham and I chat about his new music, the canine quintet periodically yap and jaw at one another in the foyer like, well … Fleetwood Mac making Rumours, probably.

Raised near Palo Alto, California, Buckingham taught himself guitar – and his unique, Scotty Moore-influenced style of fingerpicking – after becoming entranced with Elvis at age six. By the summer of Sgt. Pepper’s, he’d already been experimenting with early home recording devices. His obsessive, solitary interest in music made him something of a round peg in a square town. Few of his peers were interested in the counterculture; competitive aquatics were more their thing.

In his sophomore year at Menlo-Atherton High School, a new girl – a junior – who shared some of his musical interests transferred in: Stevie Nicks. She eventually joined Buckingham’s acid-rock band, Fritz, but by the late 1960s they had realised they worked better as a duo, professionally and romantically.

Nicks is another matter: save for a brief email she sent to Buckingham after his bypass, the two haven’t spoken

The pair relocated to Los Angeles and began working on material that showcased their tight harmonies and Buckingham’s wailing, knotty guitar playing. But what they thought was their big bang – the 1973 release of their first and only record as a duo – turned out to be more of a whimper. The moment that would actually change their lives forever seemed pretty ordinary at the time. One day Mick Fleetwood, a drummer trying to keep his band together after the departure of its lead guitarist and singer, happened to be testing out the equipment at Sound City Studios. To showcase the sound system’s power, engineer Keith Olsen played him the screaming solo from Buckingham Nicks’ “Frozen Love”.

Who was this guitarist? Would he be interested in joining Mick’s band? Only if his girlfriend could join too, Buckingham told him.

In the post-Peter Green era, Fleetwood Mac always seemed more like a random group of people stuck together in an elevator than a band – a lanky British giant, a West Coast sorceress, a nervy guitar virtuoso, a serene songbird, some guy who always seemed like he would rather be sailing – which was of course part of its magic. As the members’ romantic relationships sparked and sputtered, their peculiar alchemy and soap-operatic personal lives fuelled a stretch of timeless rock albums.

When we meet up again, Buckingham escorts me to his home recording studio, in the pool house’s basement. The night before, Buckingham mentioned, some younger neighbours had thrown a raucous party with a DJ, so the guitarist of one of the more notoriously hard-partying bands in rock history had to knock on their door and ask them to keep it down.

Even if those young neighbours didn’t recognise him, they likely would have known the tunes. More than almost any other band of the 1970s, Fleetwood Mac’s music has maintained an age-defying relevance: “We started seeing two or three generations of people at our shows,” says Buckingham, “and you start realising that you must be doing something right.” He has also appeared on recent albums by The Killers and Halsey. “He was so easy to work with, we even tried bribing him to be in the band,” the Killers drummer Ronnie Vannucci Jr says via email.

Proof of the Mac’s continued popularity came last year, when “Dreams” from 1977 was the soundtrack to a wildly popular TikTok challenge, and re-entered the Billboard charts. Buckingham filmed his own version of the meme, atop a horse, even if he didn’t realise that’s what was happening at the time. “My daughter made me do that,” he says. One day when they were up at their stables, she innocently asked him to pick up some Ocean Spray. TikToks “are like, five seconds or something,” he adds with a shudder. “Isn’t the attention span short enough already?”

A few weeks before their viral moment, Buckingham had reached out to Mick Fleetwood in the wake of Green’s death: “We both just adored Peter Green.” The two have begun talking and texting again (“Mick and I are soul mates,” he says), though recent plans to meet face-to-face for the first time in more than three years were thwarted when someone in Fleetwood’s circle tested positive for Covid-19.

In an interview with Rolling Stone earlier this year, Fleetwood expressed optimism that Buckingham may one day rejoin the band for a proper farewell tour. “Somehow,” Fleetwood said, “I would love the elements that are not healed to be healed.”

Nicks is another matter: save for a brief email she sent to Buckingham after his bypass, the two haven’t spoken. Buckingham isn’t sure what it would take to get them to hash things out, but he is open to mending fences. “I’ve known Stevie since I was 16, so I would like to think there’s a better way for us to finish up than we finished up,” he says. “Not just for Fleetwood Mac and for the legacy, but just for the two of us.”

Still, he says that after “the 43 years we’d been together” weathering more serious storms, the relatively small disagreements that he believes led to his ousting “dishonoured the legacy”.

But aren’t those disagreements also part of the legacy and the emotional authenticity of Fleetwood Mac?

“When you have just one super-creative megastar in a band, that’s pretty hard to handle. In this case, you have five, and three of them who can write and sing their own records,” says Cavallo. “When they’re contained inside of a band, that struggle and competitiveness can create amazing things,” he adds. The flip side, though, is that “the emotional part, the drama part, it doesn’t end. It’s not going to end, ever.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments