Keith Jarrett: Agony and ivory

He grunts, he swears and rants … anything can happen at on of his gigs. Phil Johnson celebrates the last piano giant

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When the jazz pianist Keith Jarrett takes the stage of London's sold-out Royal Festival Hall at 7.30pm on Monday week – and if you're going, don't dare to be late, or cough, or fidget – he will be met by whoops, cheers and wave after wave of tumultuous applause: what someone called "the sort of ecstasy that might greet a returning prophet". As he fiddles with his piano stool before composing himself for what is sure to be a marathon assault on the keyboard, the adoration will likely turn to nervy expectation, for a solo concert by Jarrett is a leap into the unknown, for audience and performer alike.

An improviser who really does make it up as he goes along, Jarrett is the musical equivalent of a high-wire act without a net, and there's always the possibility of a metaphorical fall, or a very real tantrum. It can even end in tears, witness his last RFH show in 2008, when after five triumphant encores Jarrett departed in distress. In the unusually revealing notes to the live recording Testament: Paris/London (ECM), his wife of 30 years had just left him, and he'd only agreed to the hastily arranged concerts to take his mind off the resulting depression: "I was in an incredibly vulnerable emotional state, but I admit to wondering if this might not be a 'good' thing for the music."

Just the sight of couples doing Christmas shopping in the London streets was enough to send him fleeing back to his hotel, curtains drawn for consoling darkness.

His most famous record, the Koln Concert of 1975, was also a product of stress. Arriving at the venue, the Cologne Opera House, after a long drive from Zurich and a week of sleepless nights due to a back ailment for which he had to wear a brace, Jarrett discovered that the correct piano had been replaced by an inferior baby grand, a rehearsal instrument. He tried to cancel the late-night concert, and only agreed to a planned recording going ahead as a "test". It went on to shift 3.5 million copies, becoming the best-selling solo piano album ever, in any genre.

And yes, there have been strops. At another RFH concert, with his trio in 1992, when drummer Jack DeJohnette spotted a red light in the stalls that could have come from an illicit recording device, Jarrett stopped playing and started to lecture the audience about their responsibilities to the artist. It turned out to be an LED on the mixing desk. Then there was the infamous Umbria Jazz Festival incident of 2007. "I do not speak Italian," Jarrett tells the audience in Perugia, "so someone who speaks English can tell all these assholes with cameras to turn them fucking off right now."

He was banned, and later apologised. But it's not hard to feel a sneaking sympathy, for Jarrett operates at a consistently high musical level. And if he is more comfortable with music than with life, that's only to be expected from a prodigy from Allentown, Pennsylvania, who played his first engagement at the age of six (Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and a composition of his own). "I grew up with the piano," he told his biographer, Ian Carr. "I learned its language as I learned to speak."

With a genius IQ, he started school in the third grade. "I was two years younger than everyone else. It wasn't that much fun!" If his manners might sometimes be found wanting, consider the scatalogical language of Mozart. The Wolfgang analogy is appropriate, for Jarrett combines the "You hum it and I'll smash it up!" iconoclasm of the authentic jazz genius with the lost tradition of the classical improviser who, like Mozart and Beethoven, could dash off an extempore cadenza.

Totally immersed in his music, Jarrett may moan or grunt along as he plays. But he's Keith Normal compared with classical grunter the late Glenn Gould, whose neuroses could bankroll a pharmacy, and often did.

There has been real pain, too. Now 67, Jarrett was all but silenced in mid-career by an energy-sapping malaise similar to ME, and it's only in the past seven years that he's been able to return to solo performance. He also had to watch umpteen episodes of Ken Burns's Jazz, the TV series for which his nemesis and fellow former Jazz Messenger Wynton Marsalis acted as consultant, without hearing his name mentioned once.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

"Who's really talking about individual achievements now, even in jazz?" Jarrett told me in a rare interview before another RFH show in 2000. "You read in the New York Times about how the need for the solo is retreating, and that it's a good thing. I just am not willing to make that excuse, and I would ask why are there not good jazz soloists who you don't get bored by after 10 minutes? What I hear around me is not moving me at all." Ouch.

But the best of Jarrett is close to the best of all music I know. Unlike most recent jazz, which can be self-referential to the point of solipsism, Jarrett deals in big emotions and big ideas: life, the universe, everything. Keith Jarrett is definitely weird, but pianists are often odd introverts. In jazz, while the horn-men get to sashay around the stage, the pianist has to sit chained to a big wooden box, holding everything together for hours on end. In solo performance, there's no one else to take up the slack, and with Jarrett, there may not even be a conventional tune to hide behind. Instead, what you get is a long-haul flight of sustained lyrical invention that can sound as perfectly composed as an operatic aria.

It's also one of the great dramatic spectacles as Jarrett, head bowed so low it's almost touching the keyboard, moans along in ecstasy as he plays. You can imagine the shades of Wolfie, Ludwig and all the great composer-improvisers of the past standing by his shoulder, looking on.

Keith Jarrett, Royal Festival Hall, London (0845 875 0073), 25 Feb (returns only)

Genius at the keys

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91)

Like any good jazz musician, Mozart could improvise on the spot, used his ear to complete what he couldn't sight-read at speed, and abandoned commissions if he thought he might not get paid. According to a contemporary: "He would improvise fugally on a subject for hours, and this fantasia-playing was his greatest passion."

Art Tatum (1909-56)

Partially-blind pianist Tatum blended the "stride" style of Fats Waller with the swing of Earl Hines to create elegant arabesques. His reinventions of shopworn popular songs such as "Tea for Two", define jazz sophistication. He came to specialise in solo performance and recordings partly because other musicians found it difficult to keep up. He also loved to drink beer, and died of complications arising from kidney disease.

Glenn Gould (1932-82)

The classical pianist revered more than any other by the jazz fraternity for his feeling and freedom of interpretation. Canadian genius Gould was also the most eccentric: he would only perform sitting 14 inches from the floor on his father's old chair, now in the National Library of Canada. The recording studio had to be heated to tropical temperatures. And he moaned as he played. His 1981 Bach Goldberg Variations, which Jarrett has also recorded twice, is a groaning and grunting masterpiece.

Brad Mehldau (B.1970)

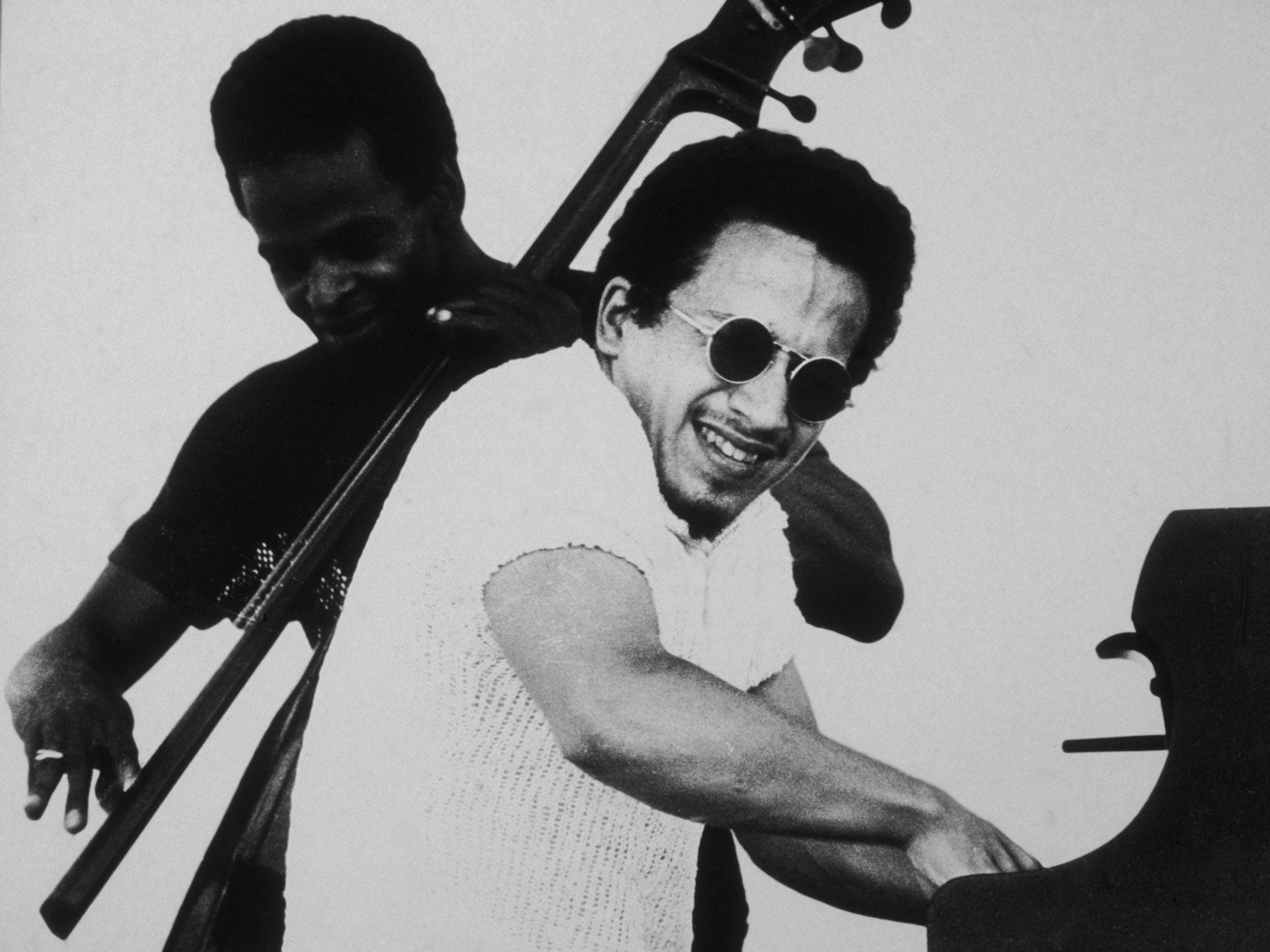

The current jazz piano genius (left), whose personal eccentricities are yet to fully show through (although he can throw the odd hissy fit). As well as performing swinging trios, cover versions of Beatles tunes and pellucid solo improvisations, Mehldau writes articles such as "Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Beethoven and God".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments