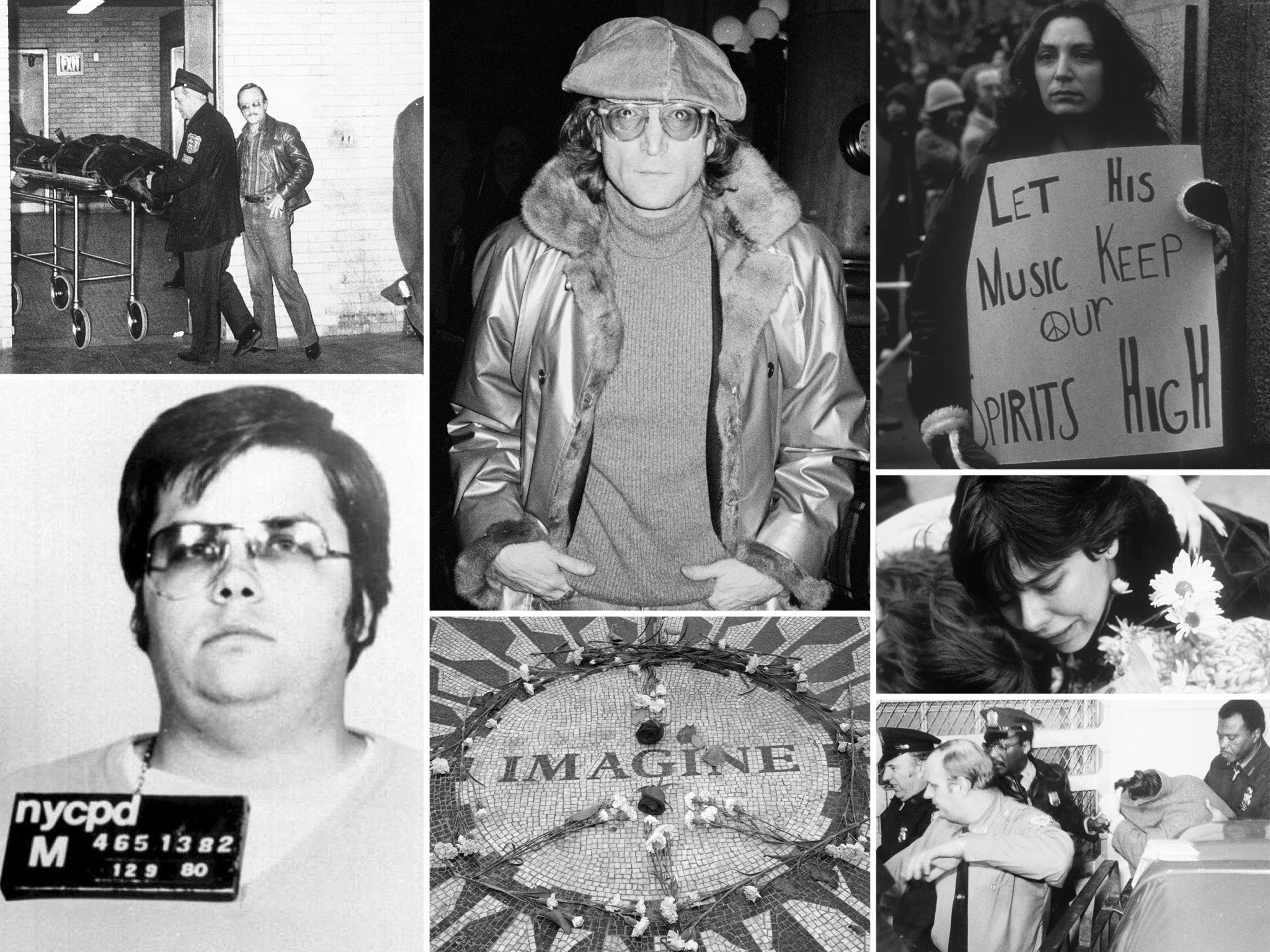

The shooting of John Lennon: Will Mark David Chapman ever be released?

Today marks 40 years since the murder of The Beatles’ founder. James McMahon looks back at the events of that fateful day in 1980, and at the man who ended the life of a legend

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two summers ago, in August, Mark David Chapman took off his prison uniform, put on his smartest clothes and – under the watchful eyes of the Wende Correctional Facility guards – made his way to the New York Parole Board building complex. This was the 10th time Prisoner 81A2860 had made such a journey, all of which had taken place within the past 20 years, having made his first appeal two decades after his initial conviction for the murder of John Lennon. Ten journeys there. Ten journeys back. And 10 rejections, despite this time Chapman seeming more contrite than he’d ever been in his many appearances in the now familiar setting. “Thirty years ago, I couldn’t say I felt shame and I know what shame is now,” he told the parole board. “It’s where you cover your face, you don’t want to, you know, ask for anything...”

The man who violently ended the life of Lennon – and any hope that The Beatles may reunite 11 years after their messy split in 1969 – is now 64. He is losing his hair and resembles little the doughy, socially inept young man who announced himself to the world 40 years ago. Five shots. Four bullet-holes in the back of Lennon, who was pronounced dead on arrival at Roosevelt Hospital, New York, a little after 11pm on the evening of 8 December 1980.

He told us to imagine no possessions and there he was, with millions of dollars and yachts and farms and country estates, laughing at people like me who had believed the lies and bought the records and built a big part of their lives around his music

Chapman was arrested metres from where the murder took place, outside the Manhattan Dakota apartment that Lennon and wife Yoko Ono shared with their five-year-old son Sean. There was the killer, leaning silently against the wall of the Dakota, reading the JD Salinger novel The Catcher in the Rye. The book, he would tell police upon their arrival, doubled as his “manifesto”. “I acted alone,” he said as handcuffs were applied.

Lennon was 40 at the time of his death. He had only just returned from a self-imposed five-year musical absence in which he had “baked bread” and “looked after the baby”. Then that October he released his first new music in years, with the release of the single “(Just Like) Starting Over”. His album with Ono, Double Fantasy, followed the next month, featuring songs he had written or finessed during a sailing trip in the summer of 1980. The trip was to be ill-fated; journeying from Newport, Rhode Island to Bermuda, Lennon’s yacht entered a prolonged storm. With most of the crew suffering from seasickness, the musician was forced to take control of the wheel alone. What followed was much meditation on the fragility of life. “I was so centred after the experience at sea,” he said, “that I was tuned into the cosmos – and all these songs came…”

Lennon and Chapman shared little in common, but both were searching for something. Just a few years prior, Chapman had made his own journey. He travelled to Tokyo. To Seoul. Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, Delhi and Beirut, then London, Paris and Dublin. Through his adventuring, Chapman met his wife, a Japanese American woman several years his senior called Gloria Abe. She’d been his travel agent. They married on 2 June 1979 (and remain wed to this day). They settled in Hawaii. He took a job as a night security guard and started drinking heavily. In September 1980 he wrote a letter to a friend. “I’m going nuts,” it read. It was signed “The Catcher In The Rye”. Salinger’s meditation on alienation has a dark legacy; the book was found in John Hinkley Jr’s hotel room after his attempt on President Ronald Reagan’s life in 1981. Robert John Bardo was carrying the book when he murdered the model and actor Rebecca Schaeffer in 1989.

It’s long been believed that Chapman’s plan to kill his idol was formulated in the midst of his heavy drinking. In recent years Chapman has claimed that his hit list extended beyond Lennon. In 2010, he claimed he’d chosen Lennon “out of convenience”. It could have been Paul McCartney, Elizabeth Taylor, talk-show host Johnny Carson, former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, actor George C Scott (famous for turning down the Best Actor award at the 1970 Oscars), even the aforementioned Ronald Reagan. Hawaii governor George Ariyoshi rounded out the list. It’s been said the musician Todd Rundgren was a target (Chapman was wearing a promotional T-shirt for Rundgren’s album Hermit of Mink Hollow when he was arrested). David Bowie once claimed he was “second on the list”.

So at that point, I had abandoned all of the plans and was going to throw the gun in the river and that type of thing and come back and everything was going to be OK. Of course, that didn’t happen

The question as to why Chapman killed John Lennon has never truly been answered. He’s given conflicting versions of his rationale for decades – citing his spiritual beliefs, his own desire to become famous, even that killing Lennon would help promote his beloved Catcher in the Rye – almost as if he’s still trying to make sense of the event himself. He had no criminal convictions prior to the murder. He’d loved The Beatles almost all his life. Lennon was his hero. As a teenager, the British band’s vivid, colourful pop provided him with a place to escape to when the fists of his violent US Air Force sergeant father reigned down upon him. By 14, he was experimenting with LSD and missing classes at Columbia High School, Decatur, Georgia. “The Beatles then were into long hair, beards, meditation, and drugs,” he said. “The Beatles were into things that fit my life perfectly.”

Unquestionably, the teenage Chapman was also already showing signs of mental instability. Most nights he would lay in his bedroom, imagining he was the “king” of a tiny race of people who lived in the walls. Generally, the appeal of his sovereignty over the “Little People” was their adoration (“I was their hero and was in the paper every day and I was on TV every day!”) but, he would later tell the journalist Jack Jones, “sometimes when I’d get mad I’d blow some of them up. I’d have this push-button thing, part of the [sofa], and I’d like, get mad and blow out part of the wall and a lot of them would die. But the people would still forgive me for that, and, you know, everything got back to normal. That’s a fantasy I had for many years.” Prior to killing Lennon, Chapman would say that the little people in the walls had come back.

And around this time he also discovered religion, attending a retreat held by the Chapel Woods Presbyterian Church when he was aged 15. He found the experience deeply affecting. He stopped taking drugs. Put away his hippie clothes. Started wearing a suit and carrying a bible at all times. He even began to leave religious tracts in the school lockers. “At some point I lifted my hands and I said, ‘Jesus come to me. Help me,’” he recalled. “And that was my time of true spiritual rebirth. That night I came to a door. When I opened the door and let God come physically into my heart, I felt cleansed. I felt totally forgiven and totally renewed.” Crucially, he also began to sour on Beatle John.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

When Lennon had told the Evening Standard in March 1966, as part of the paper’s regular franchise “How does a Beatle live?”, of his belief that the Beatles were now more “popular than Jesus”; that perhaps rock music would outlive Christianity, it drew little controversy. When the quote made it to the United States a few months later, via a reprint in the teen magazine Dateline, it induced apoplexy. Across the bible belt, Beatles records were set alight on huge bonfires. Radio stations stopped playing their songs. The Ku Klux Klan picketed performances in Washington, DC and Memphis, Tennessee. At the latter, someone threw a firecracker on stage. Briefly the band thought it was gunfire. The Beatles had headed to America to promote their seventh studio album, Revolver. They talked little about the record. They, and John – right until the very end – would never tour again.

Chapman was smarting. His dislike would only intensify with each passing year. Lennon, he decided, was a hypocrite. The release of “Imagine” in 1971 – a song Chapman considered communist – was perhaps the final straw. “He told us to imagine no possessions,” he would say, “and there he was, with millions of dollars and yachts and farms and country estates, laughing at people like me who had believed the lies and bought the records and built a big part of their lives around his music.” The cod theological pondering of “God” on 1970’s John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album – “I don’t believe in Jesus, I just believe in me” – probably didn’t help.

Chapman had made a trip to New York in October with the intention of doing the deed then. While there, he watched the film Ordinary People, notable for being the directorial debut of Robert Redford. Something about the movie spoke to him. “I came out of the theatre and called my wife and for the first time, I told her,” he said. “I told her what I was going to do, and I was crying. And I said I thought about life and thought about my grandmother, and I told her, I said: ‘Your love has saved me. I’m coming home.’ And she said, ‘Just come home. Please, come home.’ So at that point, I had abandoned all of the plans and was going to throw the gun in the river and that type of thing and come back and everything was going to be OK. Of course, that didn’t happen.” After returning home and making an appointment with a clinical psychologist he wouldn’t keep, he returned to New York on 8 December.

Chapman spent most of that day at the Dakota. No-one thought anything of it; as well as Lennon and his family, an assortment of celebrities including Leonard Bernstein and Lauren Bacall called the complex their home. Fans would lurk outside the building all the time. Chapman had left his £64 ($83) a night room at the Sheraton Centre downtown early, but had missed Lennon when he stepped out of a cab and entered the Dakota that morning after becoming distracted. He was much more focused a few hours later when he spotted Lennon’s housekeeper, returning from a walk with then five-year-old Sean. “You’re a beautiful boy,” said Chapman, referencing the song John had written about his younger son, “Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)”, and shaking the little boy’s hand.

At 5pm, Lennon and wife Yoko Ono left the building. They had an appointment at the Record Plant Studios on West 44th Street. As the pair walked towards their limousine, Chapman approached John and asked if he’d sign his copy of Double Fantasy. Lennon did, writing “John Lennon 1980” on the sleeve. During his wait at the Dakota, Chapman had befriended an amateur photographer called Paul Goresh. He captured the act of Lennon signing the album for Chapman on camera. When Lennon had gone, Chapman panted excitedly: “John Lennon signed my album! Nobody in Hawaii is going to believe me!” He tried to talk Goresh into waiting around with him for Lennon to return later. He could get his album signed too. “You never know if you’ll see him again!” Chapman told his new friend. Six hours later, John Winston Ono Lennon was dead. Lennon and Ono had returned a little after 10.50pm. As their limousine pulled up to the Dakota’s archway entrance and Lennon stepped out onto the pavement, Chapman dropped to one knee, firing five hollow-point bullets from his .38 special revolver into Lennon’s back and shoulder. His lung was punctured, his left subclavian artery torn. Two hours after that, Chapman would get on his knees and pray to God, pleading for the ability to rewind time.

In August earlier this year, Mark David Chapman took off his prison uniform, put on his smartest clothes and made his way to the New York Parole Board building complex once more. There the three-member board were in possession of a letter from Yoko Ono – still a resident of the Dakota, incidentally – in which she pleaded for Chapman to remain imprisoned, as she’s done for every previous appeal in the past 20 years. It was unthinkable that the judgment, in this year of all years, would be any different to the 10 that have preceded it. And as anticipated, Chapman returned to his cell, stripped and put on his prison uniform once more. Just him and his Little People. Just him and his regret.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments