The death of Jimi Hendrix: the unanswered questions

Was the guitar genius unconscious for hours while a girlfriend and roadies removed drugs from the scene? Did someone pour red wine down him until he died? Were there people who wanted him dead? Was his lover to blame? Mark Beaumont examines the evidence in a new book

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lost hours and missing drugs. Mafia debts and CIA hitlists. Police surveillance and suspicious testimonies. Every superstar tragedy prompts questions and conspiracy theories, but the death of Jimi Hendrix, who joined the notorious 27 Club 50 years ago today, remains mired in controversy. Some close to him claim it was suicide, others a terrible accident, some that he was murdered by underworld figures or secret service operatives. The events of 18 September 1970 are forever caught in a confusing crimson haze.

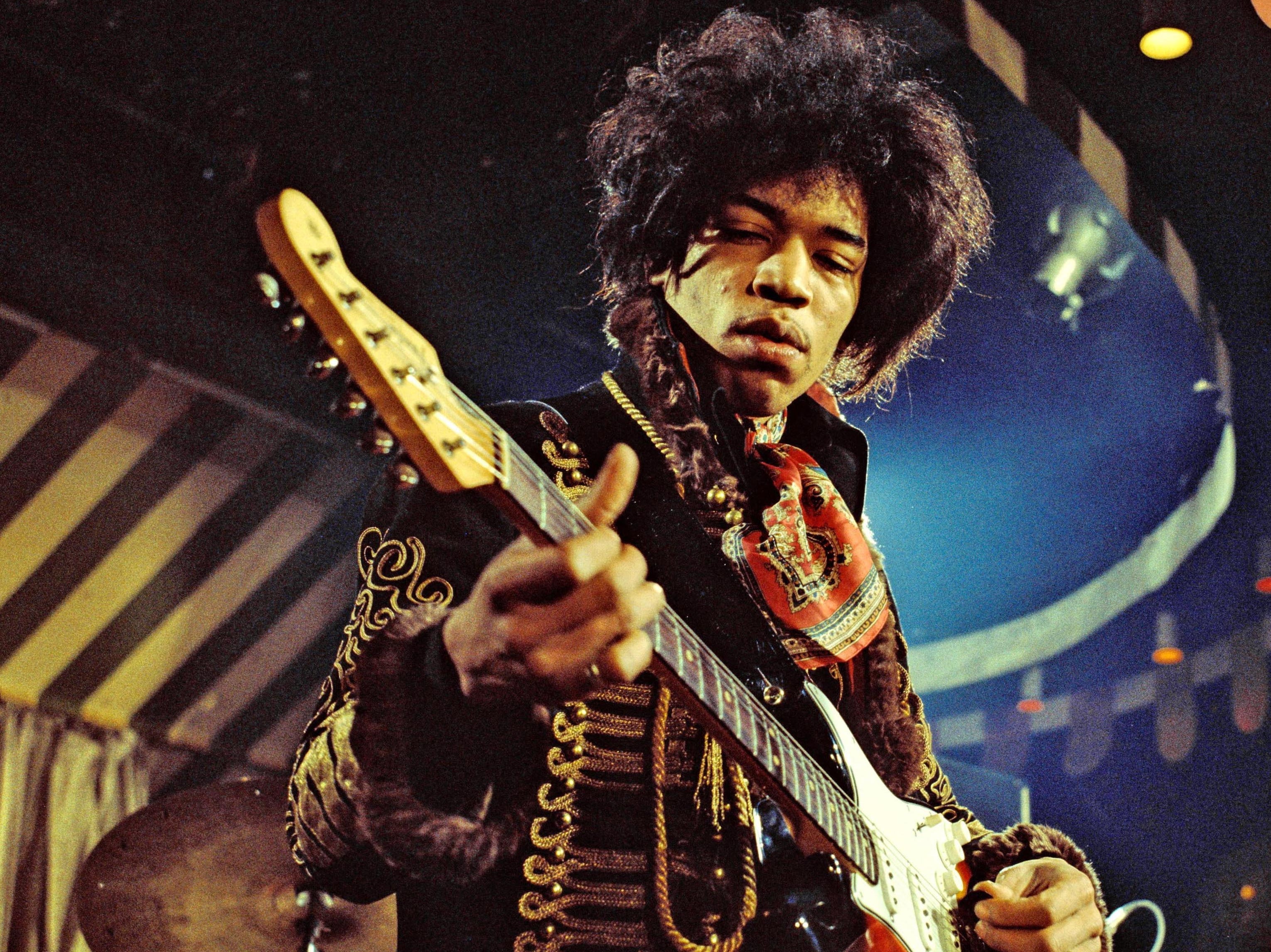

What’s beyond doubt is his genius. By 1970, Hendrix’s three studio albums, Are You Experienced (1967), Axis: Bold as Love (1968) and Electric Ladyland (1968) had established the Seattle-born guitar hero as a pivotal and influential figure in the Sixties counterculture in the space of just four years. His records, where raw urban blues met psychedelia and funk, shot through with lightning-bolt guitar work that made Cream sound curdled, were the crucible of hard rock to come, even if many of his imitators would favour macho swagger over his stylish dandy aesthetic. His knack for totemic, confrontational showmanship – the war-torn “Star Spangled Banner” at Woodstock; the flaming guitar at Monterey – provided some of the defining moments of the age.

He also had a propensity for hedonism and excess which saw him, come the late summer of 1970, in a dangerous state of flux. His girlfriends were many, his capacity for drug-taking notorious, his moods unpredictable and violent, particularly when he’d been drinking heavily. Trouble stalked him; the previous year he had been kidnapped by low-level mafia thugs while buying drugs in a New York City nightclub, and only released unharmed on the orders of the mob bosses. With his Jimi Hendrix Experience group disbanded, major festival shows marred by his drug-taking, his health deteriorating and the working relationship with his manager Michael Jeffery – a controlling, mob-connected figure who worked Hendrix to the brink of exhaustion and kept the guitarist’s finances opaque at best – on the verge of collapse, he told friends and journalists that he felt aimless, hounded and unable to trust anyone around him.

A sense of fatalism had descended. When a clairvoyant’s tarot reading on a 1969 trip to Morocco turned up the death card, Hendrix took the prediction literally: “I’m going to die before I’m 30,” he told a friend. Over his final year he’d count down his remaining months, and two days before his death he ran into a journalist friend named Sharon Lawrence at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in Soho, too intoxicated to play his planned guest spot at a residency by Eric Burdon’s band War, and told her, “I’m almost gone.”

His final weeks were a tangle of madness and misfortune. The 600,000-strong crowd at the Isle of Wight Festival were lucky to catch his last truly legendary performance, as his subsequent European tour was a sharp downward spiral. Arriving for a show in Gothenburg, Sweden, Hendrix was met by former student Eva Sundquist, who insisted he’d fathered her son James after a Stockholm show the previous year – Hendrix’s second paternity claim. That night’s show was a mess, a wasted Hendrix forgetting songs mid-solo and drifting into others. At the next gig in Denmark he had to be helped onstage by his new fiancée, Danish model and actress Kirsten Nefer, suffering from a fever and lasted just three numbers. His final show, at the Open Air Love & Peace Festival on Fehmarn Island in Germany on 6 September, was anything but loving and peaceful – a storm had stopped Hendrix playing his scheduled slot the previous night and when he finally made it onstage he was booed and jeered. At the close of his set, the Hells Angels security, on a burning and looting rampage, stormed the stage to set fire to it, shooting a roadie in the leg.

Returning to London and cancelling his remaining dates, Hendrix swiftly saw his support network collapse around him. Nefer was due back on a film set, and his key protector, bassist Billy Cox, who had played with Hendrix at Woodstock and on the 1970 tour, had drunk punch spiked with LSD at the Gothenburg show and, suffering paranoid delusions that he was being poisoned, flew back to the States. “If Billy Cox had been around it wouldn’t have happened at all,” says biographer Philip Norman, author of a new Hendrix book, Wild Thing: The Short, Spellbinding Life of Jimi Hendrix. “He’d exhausted himself, completely worn out by this awful tour that he’d been on through Europe.”

Cut free in London, Hendrix flitted. Friends and old flames saw him, looking ashen, thin and tired, out shopping on the King’s Road, taking in arthouse cinema, making his last ever appearance onstage – with Burdon’s War at Ronnie Scott’s, on his second attempt – or in private, to discuss how best to disengage himself from his contract with Jeffery. But, in Nefer’s absence, his final three days were spent largely with Monika Dannemann, a 25-year-old German ex-ice skater with whom Hendrix had shared brief trysts in Dusseldorf and London the previous year. Dannemann would later claim that the pair had fallen deeply in love and plans for their marriage were under way.

“She seemed to be an obsessive fan who could actually harm the object of their adoration,” Norman argues. “Her claim that she was engaged to him and was the love of his life seemed very questionable.”

Hendrix had invited Dannemann to see him in London, where she booked into a bedsit-style room at the bohemian Samarkand Hotel in Notting Hill. She would describe Hendrix’s final days as wrapped up in idyllic romance, writing, painting and swearing undying love for each other at the Samarkand; his last creative work, a poem called “The Story of Life”, was composed there, featuring the fateful line, “The story of life is quicker than the wink of an eye”.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Others paint a rockier picture. On 17 September, Hendrix’s last day alive, the pair were randomly spotted in traffic by Lloyds underwriter Philip Harvey – son of Tory MP Arthur Vere Harvey – and invited to his well-appointed apartment for drinks, where Dannemann berated Hendrix in the mews courtyard for half an hour when he began showing interest in Harvey’s two flirtatious female companions. After a late-night meal at the Samarkand, Dannemann then drove Hendrix to a party at music publisher Pete Kameron’s home at 1.45am. Dannemann wasn’t invited – another of Hendrix’s girlfriends, Devon Wilson, would be there – and when she came to collect him at 3am, Dannemann was berated from the window to “leave him alone”.

The following hours remain shrouded in mystery, with almost all of the eyewitness accounts changing over time until the truth of the matter slipped between the gaps. According to Dannemann, she and Hendrix returned to the Samarkand and stayed up talking – or, in other statements, arguing – until around 7.15am. He had taken a “brown bomber” amphetamine pill at Kameron’s party and, having often struggled to sleep over previous months, sometimes for days at a time, asked Dannemann if she had any sedatives he could take.

She offered him a strong German sleeping pill called Vesparax, each tablet a double dose for easing the injury which had stymied her skating career. It’s unknown how many of the tablets Hendrix took. According to a friend, folk singer Buzzy Linhart, the day before his death Hendrix had complained of being awake for days and a New York doctor had advised Hendrix to take three doses of his regular sleeping pill, considering his tolerance to such drugs. Three or four double doses of the far stronger Vesparax would have been a danger in his weakened state. Dannemann believed he may have taken up to nine.

Dannemann’s story of the timings and events of the following morning changed more than a dozen times over the coming years, and is riddled with inconsistencies. In some, she woke around 9am, in others 10.20am or closer to 11am. In her most generally accepted account, finding Hendrix “asleep”, she went out for cigarettes. On her return, she noticed vomit around his mouth and couldn’t wake him.

Hoping to find a number for his Harley Street doctor, she called her friend Alvenia Bridges who had spent the night at the Hotel Russell with Eric Burdon. Bridges would claim that Dannemann was hysterical, saying that Hendrix was unconscious and vomiting; she advised her to turn him over to stop him choking, but she failed to do so. Burdon’s story would also alter over time, but he’d variously claim that Dannemann had gone out for cigarettes after calling Bridges and had to be convinced, on a second call, to phone for an ambulance as she was worried about the drug paraphernalia littering the room and afraid that Hendrix would be angry to wake up feeling fine, handcuffed to a hospital bed.

An ambulance was finally called at 11.18am, arriving at the Samarkand at 11.27am, over two hours after Dannemann’s earliest proclaimed rising. Details of the intervening period are confused at best. Burdon made his way to the scene, in some of his accounts arriving while Hendrix was still there, in others just as the ambulance was departing. “When I arrived there ... I think I saw Jimi on the bed,” he told Hendrix’s long-term girlfriend and “Foxy Lady” inspiration Kathy Etchingham. “I didn’t want to, you know, look at it, you know, I didn’t want to look at the mess. We had to be there before. We got the guitars out, we got the drugs out of the place...”

At some point, either before the ambulance arrived or before the police came to interview Dannemann that afternoon, a clean-up took place at the Samarkand involving Burdon and various roadies and helpers. Terry “The Pill” Slater was filmed by police burying drugs in a communal garden (which were missing when he returned for them the next day), suggesting that this happened later in the day, after police had designated the Samarkand a potential crime scene. Yet, according to Etchingham’s book Through Gypsy Eyes, Slater remembered seeing Hendrix on the bed looking “knackered”, and Burdon’s claim that he’d arrived at the Samarkand while there was still morning dew on the cars led Philip Norman to believe that Burdon and his associates cleaned the apartment before the ambulance was called, while Hendrix could still have been helped.

“This was a very beautiful Indian summer [so] that would’ve been really early in the morning, dawn,” he says. “The ambulance wasn’t called, as the log showed, until after 11 in the morning. [There were] these lost few hours between the time that people went to this bedsit in the basement of this hotel and the time he was taken in an ambulance to hospital. Several hours passed when it seems quite clear he could’ve been resuscitated and saved. Instead there were people there getting rid of drugs and panicking around him without doing anything to help him.”

There were even discrepancies in reports from the medical teams who treated Hendrix. The ambulance crew reported that they found the apartment empty and Hendrix unresponsive, his throat entirely blocked with vomit: “We tried to revive him, but we couldn't,” paramedic Reginald Jones told Etchingham. “The vomit was all dried. He'd been lying there for a long time. There was no heartbeat. He was blue, not breathing and not responding to light or pain.”

An unofficial 1993 investigation by former Sussex police superintendent Dennis Care, however, suggested that Hendrix may still have been alive, albeit barely, on his arrival at St Mary Abbot’s hospital – where he was rushed to a resuscitation room rather than sent to directly to the morgue – or had died in the ambulance. Dr John Bannister, the on-call registrar who had tended to Hendrix that day, believed him to have been dead for hours, but would claim he was covered in red wine. “The amount of wine that was over him was just extraordinary,” Bannister was quoted in The Times in 2009. “Not only was it saturated right through his hair and shirt, but his lungs and stomach were absolutely full of wine … We kept sucking him out and it kept surging and surging … He had really drowned in a massive amount of red wine.”

Hendrix’s autopsy, though reporting 400ml of “free fluid” in his left lung, mentioned no wine in Hendrix’s lungs or stomach and little alcohol in his bloodstream; his death certificate listed cause of death as “inhalation of vomit [due to] barbiturate intoxication”. But such details, combined with the contradictory nature of almost every account surrounding Hendrix’s death, have allowed fanciful theories of murder and assassination plots to take root. There were certainly people and organisations with motives. The FBI’s Cointelpro (Counter-Intelligence Program) operation, designed to neutralise inspirational black figures, had files on Hendrix and his name was listed among America’s most subversive figures by the CIA as part of a surveillance programme called MHCHAOS.

“According to his brother [Leon], [Hendrix was] on a list on the same level as Osama Bin Laden later on after 9/11,” Norman says. “There were credible reasons for thinking that he might have been murdered by the American government as a threat, at a time of extreme paranoia, when they had these contingency plans for rounding up people they thought were threats and putting them in camps in the early Seventies. He had started to become affiliated with black radical groups like the Black Panthers … and that would freak out the government or the CIA or the FBI because he had such influence over white audiences.”

Stories of underworld hitmen surfaced too. In 1975, Dannemann claimed in an interview that Hendrix had been murdered by mobsters: “I do believe that he got poisoned, that he actually got murdered,” she told biographer Caesar Glebbeek. “There is something really behind the whole thing, and there’s quite a powerful group behind all that. I think it is the mafia.” Then, in 2009, The Animals’ one-time roadie James “Tappy” Wright released a memoir alleging that Jeffery, before his death in a plane crash in 1973, had drunkenly confessed to Jimi’s contract killing to him. The manager, Wright attested, had been $45,000 in debt to the mafia and, fearing Hendrix was preparing to cut ties with him, was left with no option but to try to cash in on a $2m life insurance policy he’d just signed for Hendrix. According to Wright’s account, Jeffery admitted to hiring “some villains from up north” to drown his charge in the night.

“That doesn’t really hold water that much because he was still going to be connected to that dreadful manager for some time after the actual management contract ended,” Norman argues. Indeed, Jeffery was set to continue to make significant money from Hendrix’s album advances and revenues well into the Seventies, and never received a penny from the insurance claim which, according to Hendrix’s US manager Bob Levine, was actually taken out by his record company Warner Brothers.

In 2011, Levine told musicradar.com that Wright had privately admitted to inventing the story to sell his book. “Jimi Hendrix was not murdered,” he said. “The whole thing is one giant lie … I told Tappy, ‘What are you doing making up this story? So you want to sell books – why do you have to print such lies?’ And he said to me, ‘Well, who's going to challenge me? Everybody's dead, everybody's gone. Chas Chandler [Hendrix co-manager], Michael Jeffery, Mitch Mitchell [Jimi Hendrix Experience drummer], Noel Redding [Experience guitarist]… they're all gone. Nobody can challenge what I write.’”

The likeliest available explanation for the presence of red wine came from Sharon Lawrence, who wrote in her 2005 book Jimi Hendrix: The Man, the Magic, the Truth that, on a phone call in 1996, she directly asked Dannemann if she’d poured wine down Hendrix’s throat herself. Dannemann’s reply, she claimed, was “it was all untidy. He was messy. I thought it would help”. Lawrence was convinced Hendrix’s death was suicide.

Norman, on the other hand, believes it was a simple case of confusion and ill-judgement spiralling into tragedy. “I think it really was that more mundane [explanation] of accidentally taking too much, and not being helped when he could have been helped,” he says. “I think it’s that he was befuddled, not high and not particularly drunk, but just slightly confused and took double the dose that he thought he was taking. Much later another expert said that he was in such a poor state that even the single doses that he took might have finished him off because he was in such a low state of health … He was in a state of complete physical exhaustion at the time and London was full of people who supposedly cared about him and had some sort of responsibility for him and none of them seemed to be able to save him from this preventable, tragic death.”

With Dannemann’s suicide in 1996, the truth of Hendrix’s final hours likely followed her to the grave. Like the man himself, Hendrix’s passing remains an enigma, an impenetrable kernel of rock’n’roll folklore clouded by rumour, hearsay, lies and legends. But his essence – flamboyance, passion, style, confrontation, virtuosity – infuses and inspires the best music to this day. In that sense, he’s still out there, kissing skies.

Wild Thing: The Short, Spellbinding Life of Jimi Hendrix is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments