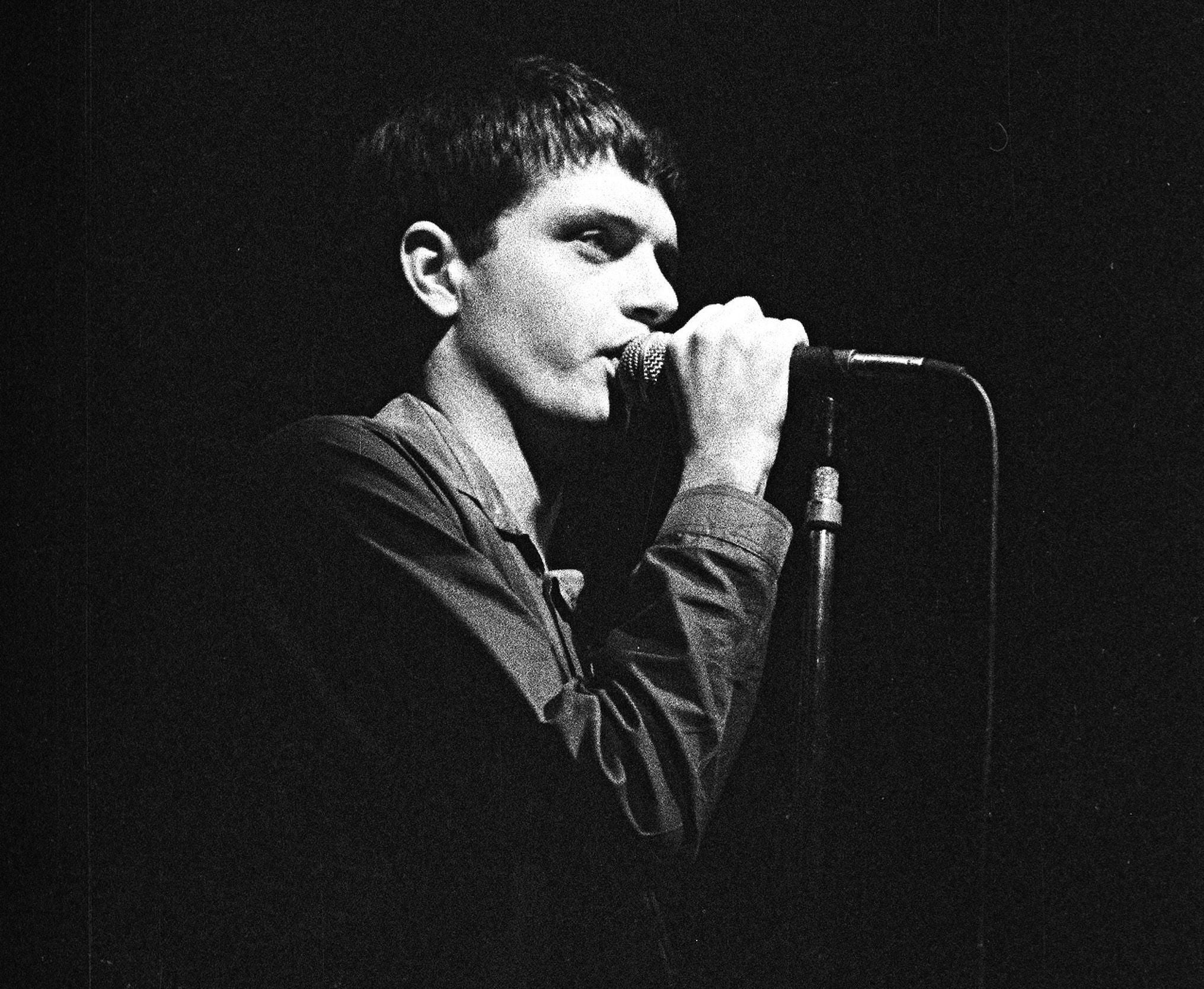

Joy Division on the death of Ian Curtis: ‘Listening to Closer, you think, f***ing hell, how did I miss this?’

Forty years on from the day the singer took his own life, Mark Beaumont talks to bandmates Peter Hook and Stephen Morris plus Tim Burgess, Grian Chatten, Orlando Weeks and Jon Savage about the man, the artist and his legacy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sunday 18 May 1980 wasn’t a day that rocked the globe. Not in the way that Monday 8 December would, the day John Lennon was murdered. The death of Ian Curtis of Joy Division, who hanged himself in his kitchen aged 23 on the eve of an American tour – the culmination of spiralling depression, worsening epilepsy and marital breakdown – passed almost unnoticed by the mainstream press.

Its reverberations, however, would be felt through the music world for decades. Curtis’s visceral intensity, poetic candour and devastating tragedy infiltrated the underground scene and lay the bedrock for much of the more glowering, portentous and meaningful alternative music to come. On the 40th anniversary of his death, we spoke to his bandmates, disciples and descendants to prise open his influence and enigma and glimpse the man behind the myth.

THE BANDMATES: PETER HOOK, Joy Division bassist

“I remember meeting Ian in the bar at [Manchester club] the Electric Circus. It was only a small clique that followed all the punk bands around at that time, and he was recognisable in that he was, like the rest of us, excitable. We were a group of like-minded individuals, misfits and freaks… a very incestuous, small little clique of people in the scene in Manchester.

“We recognised him pretty soon from a lot of the concerts and got talking to him. He was young, like us, he was as enthusiastic, as friendly. And he had ‘hate’ written on his back in orange paint, which was pretty weird. He was somebody that you looked at and if somebody said to you, ‘I’ll give you a million pounds to guess what he’s got written on his back’, you would not have looked at Ian Curtis, the wonderful kitten of a man that he was, and said he had ‘hate’ on his back.

“Ian was very, very likeable. He was very easy-going, until he got drunk. He was a real nice man. Very easy to, if you like, fall in love with. And then when he started singing – and don’t forget, our equipment was absolutely s***e – we couldn’t hear what he was doing but you could see what he was doing, which was putting in the same amount of passion, enthusiasm and anger. So I didn’t have to hear what he was singing about. All I had to do was look at him and his actions let me know that he was perfect for this group. We didn’t look at him and think ‘he’s got a unique voice’. To us he was just another snotty kid screaming his balls off. We were screaming our balls off with our guitars and he was screaming his balls off into a microphone.

“It was Ian that had the enthusiasm and the vision to think about what we could do. He educated us very well, musically, but he never came in and took over. He was very generous and was always up for sharing the limelight. The trouble was that he was so good, as soon as you started listening to him the occasional flash would come through this awful noise and you’d think ‘f***, that was good’. You suddenly realised that as a lyricist and as a songwriter he was in another league.

“He was a born-to-be frontman. I’ve never had the like since. The scene in Manchester turned out to be quite middle class and we didn’t fit into that scene. We would have to fight to get gigs, and Ian would fight. For the famous gig at the Electric Circus [immortalised on the 1978 live album Short Circuit – Live at the Electric Circus], we had to go and kick off at the door with Ian threatening the promoter to get on that gig because they closed that gig to us. Ian was the one who was at the front kicking off like s***. Of course, we went on and then the next thing the album’s out with a sticker on saying ‘featuring Joy Division’.

“He would never back down. If we had a gig on Friday and he’d just had a massive [epileptic] fit, he never said, ‘You know what, I can’t do the gig on Friday’. He’d go ‘f*** that, we’re doing that gig on Friday, we’ve got to’. No matter how bad his fits got, he always wanted to carry on. All we wanted to do was play so if he was going, ‘I’ll be alright’, you go, ‘thank f*** for that’. You could usually tell when he was going to go [into a fit onstage] and it was usually always to do with the lights. When the idiot lighting guy who you’d told not to flash the lights flashes the lights, he’d go almost immediately. He’d go glassy-eyed and just fix a stare, then the next minute he’d fall over and be absolutely rigid. The roadies would come on and take him off. A lot of people thought it was part of the act. Sometimes he’d recover instantly, other times it was usually me or Rob that ended up sitting on him and sit with him and hold his tongue while he stopped fitting.

“In the studio, he kept his corner up perfectly. While we were jamming and getting the songs together, he was the spotter going, ‘Oh, that sounds good, that sounds good, put that together with that bit’ because we didn’t have any tapes. Ian knew that we were fantastic. I didn’t analyse the lyrics. I think it would have felt a bit intrusive – when you saw the lyrics to ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, it was obvious that he was breaking his heart about a relationship that was over. Us working class northern males did not go around talking about how we express our feelings in song. I suppose the mystique helps. There’s hardly any footage of Joy Division, there’s hardly any interviews of Ian or Joy Division. Luckily, me, Bernard and Steven didn’t get to f*** up the mystique of Joy Division in the way we f***ed up the mystique of New Order.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“People assume that when he died it was like Nirvana but it wasn’t. The last gig we played, in Birmingham, we played to about 150 people. So we were not successful. Ian always said we’d be huge all around the world. He would sit there whenever any of us got down about everything, as you do when you can’t get a gig or a record deal or whatever. He’d always say, ‘Don’t worry, we are going to be big in Brazil. We’re going to be big here, we’re going to be big there’. It was always him that was the cheerleader, that would pick us up by the scruff of the neck and convince us to go on. He had the passion and enthusiasm every time we waned, he was amazing at that.

“In New Order, it was frowned upon to celebrate anything to do with Joy Division. But when it came to 30 years of his life I felt like I should be celebrating it. We [Peter Hook and The Light, who perform Joy Division’s albums on stage] did one gig at the Factory. I wasn’t sure if anybody would come, and we sold out. So we did two nights. And then we started getting offered gigs all around the country and then it became all around the world. The highlights for me are just too many to count. Watching grown men cry is fantastic. I’ve not got anyone reluctantly playing, and we play the music really well. The first gig I remember a young French kid coming up to me, 18, going ‘Oh, what was Ian Curtis like?’ I was thinking, ‘Jesus, he’s been dead for 30 years. He died before you were even a glimmer in François’s eyes’.

“Playing the music is fantastic because it gave me back something that I had so cruelly taken off me, which was Closer. We never got to play Closer, some of the tracks we never played as a group. Everywhere you went, the appetite for Joy Division was fantastic. It was only then that I got an insight into his lyrics and I was absolutely blown away. I felt I was privileged to be able to fulfil his wishes. We got to Mexico and we got to Brazil. We got everywhere that he wanted to go, we did America 10 times. I often go and see him, whenever something nice happens. I’m very proud of what we’ve done and every time I go and see him I say, ‘Mongolia mate, done, China, done…’”

THE BANDMATES: STEPHEN MORRIS, Joy Division drummer

“I answered an advert, rang him up and he was like ‘come round for a cup of tea’. My first impression of him was, ‘how can this bloke be a singer in a band?’ He was remarkably quiet. Not exactly mild-mannered, just a regular guy who’d been to the same school as me. I imagined something a bit more confrontational. We were all ‘Velvet Underground, yeah, I like Iggy’. He was listening to the same sort of stuff as me, just a regular lad. The other thing we had in common was a similar taste in books – he liked Burroughs and Ballard.

“We did a rehearsal to see if I was suitable for the job, and he just sat with his microphone and his lyrics, smoking away and chatting. It was strange at first because he wasn’t trying to sound like anybody else, he was just trying to be himself. He was learning how to be a singer at the same time we were learning how to be the band, so everybody was doing something quite unique. He was the perfect frontman, because when you did get to see him live, he totally transformed into this force of nature. The very first gig at Eric’s, when I saw him being Ian the singer for the first time, you’re shocked. I’d expected him to be someone very quiet who mumbles into the microphone and he didn’t do that. The best ones were the ones where he’d really get wound up, which happened quite a lot in the early days. You’d have band arguments when you’re playing some dive on Oxford Road and it’d be, ‘we’re going on last!’ and he’d get very wound up about it. When that happened, he was just this bundle of energy, rolling about on the floor. All the anger or whatever he felt all came out in his singing. It was a release.

“It wasn’t like he was putting on a show, it was just what he was. Sometimes he’d be perfectly still and sometimes he’d erupt and be all over the place. It was great, but the thing about Joy Division was that we never really talked about anything, what we were doing or what we wanted to do. Each of us had our own bit of space and we kept to it. You’d never ask Ian ‘what’s this song about?’, we’d just go into the room and play, that was all we wanted to do.

“Ian was very, very passionate about the band. He was the most belligerent about our lack of success in the early days. We all had a bit of a chip on our shoulders, but he was always like, ‘the other bands are getting on, why can’t we?’ He was very driven that we should be doing more than we are doing, he always wanted us to do more. And that makes you want to do more as well. He was doing something he’d always wanted to do, and he was very good at it.

“The one thing that really upsets me about the general perception of Joy Division and Ian particularly is that he always comes across as a morose, depressed individual, a tortured artist, where he was anything but. We joined a band to have fun and that was what we were doing. He was always having a laugh, he told terrible jokes. Do you remember [Freddie] Parrot-Face Davies? Seventies comedian, awful, awful jokes. I always remember him smiling and when you see pictures of him now there’s very few pictures of him smiling. I don’t really remember him as the picture of him with his head in his hands. He probably did that once or twice but that’s the image you’ve got of Ian, being the thinker. Most of the time he wasn’t. He was very into practical jokes. Putting jam on the car door handles, really puerile, childish stuff.

“It was in the studio when you got to hear the words. It was like he was writing little stories, his words always seemed quite inclusive, like how Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground would write stories with other people in. We thought it was great the way he was writing about other people and it sounds so real. You never once thought that he might have been writing about himself. The tragedy of it all, really, is we were all bloody grim northern bastards and you don’t talk about your emotions. It’s got to come out somewhere, all that stuff you’re keeping inside and with Ian it came out in his lyrics because there wasn’t anywhere else for it to go. It was just natural, we assumed Ian wasn’t talking about himself because nobody else did. We were stupid and selfish.

“When Ian got ill, it kind of made it worse because there was something else there and he wouldn’t talk about it. Ian’s major flaw was that he always wanted to please you. He would say what he thought you wanted to hear, and he’d say he was alright, ‘yeah, I’m fine, I’m fine’, and he wasn’t. It’s being a man again – you can’t say, ‘I’m f***in’ knackered, I feel really down, I don’t want to do this’. I think he thought he’d be letting us down and that became another thing. Towards the end, afterwards, and particularly nowadays, I sometimes wonder if I ever knew him at all, because he went through writing all those lyrics and I honestly thought they were about somebody else, and afterwards, sitting down and listening to Closer, you think, ‘f***ing hell, how did I miss this?’ If only we’d have been able to talk about what he was going through we might have been able to do something about it. But I doubt it very much to be honest, because we were so wrapped up in music and gigging, that was all we were interested in and we didn’t want to stop. Looking back now, which I did just recently, the amount of work we did in such a short time, even after Ian’s first seizure – we should’ve taken some time off and tried to sort things out, but we didn’t, we just carried on. Not as if nothing had happened, we knew something had happened, but we wanted it to all be alright, we wanted him to take a couple of tablets and everything to be OK again. Once he started on medication he became very withdrawn, which was a side-effect of the medication, and sometimes later on we’d do gigs and you could see it was draining him. Even then, you’d have thought we’d have said, ‘c’mon, maybe we shouldn’t do tomorrow night’, but we didn’t. If anything we’d do another one.

“In hindsight, there were loads of warning signs. He’d tried to kill himself once and we decided that to cheer him up, instead of cancelling the gig, we’d do the bloody gig, which was the Bury gig which ended in a riot, which is bound to make someone feel better, isn’t it? It was f***ing stupid. He was ill, and his marriage was in trouble because he was seeing somebody else [Curtis had become involved with Belgian journalist and music promoter Anouk Honoré after the band played in Brussels, although before her death in 2014 Honoré told an interviewer that the relationship had been platonic]. He’d become a father just as we did Unknown Pleasures and he was under a lot more pressure than we were and we either couldn’t see it, didn’t want to see it or couldn’t conceive of what it might be.

“The music and the story – it’s a myth, isn’t it? For me the great thing about Ian is that he never got to be s***. Joy Division never got to make the slightly dodgy third or fourth album, what you see is all there is and you can make your own story, you can take it and make it whatever you want, but it’s not necessarily 100 per cent accurate.

“Ian’s influence set in quite soon. Not long after we’d done Closer we were aware that there were a lot of bands that either sounded like Joy Division or they’d got someone singing who was trying to sound like Ian. At the time it annoys you – ‘these ripping-off bastards!’ – and you don’t think, ‘isn’t it great – when we got into playing music we were taking stuff from Iggy and The Velvet Underground and now people are taking stuff from us’. I’m sure it would’ve annoyed Ian more than anybody!”

THE EYEWITNESS: JON SAVAGE, author of This Searing Light, The Sun and Everything Else: Joy Division, The Oral History

“I saw Joy Division a lot in ’79 [and they] were very different live to the records. It was heavy in every sense, it was serious, very intense, very worked out. They wanted to have a physical and emotional impact on you. And in the middle was Ian, and Ian was something quite extraordinary. If you watch a master performer they’re not giving everything all the time, but that’s what Ian did. He’d throw himself into every performance almost like an experiment and take it as far as it would go. That makes for incredibly exciting performances. I never saw The Stooges in the early days but I’d imagine it was what Iggy was like in ’69 or ’70. It’s the total intensity of the performance. If you look at any of the live footage it is electric because he’s giving everything. Like Iggy always said, when he got onstage the electricity hit him and he became somebody else and that’s what happened with Ian. He puts himself into this state and it’s completely riveting to watch because you don’t know where it’s going to go, it’s quite dangerous and it was in fact dangerous to him. Every gig was different and Ian was, in a way, burning himself up.

“Ian was a talented writer, the lyrics are very interesting. You listen to something like ‘Dead Souls’ and ‘they keep calling me’ and it’s chilling. There were fantastic, allusive lyrics, and you get that combined with the intensity of the performance and the unique way the group sounded, and the other thing about Joy Division was that they were technological, they were forward-looking.

“Why I called the book This Searing Light was because I wanted to get away from seeing Joy Division as dark, because that was not my experience of them. They were intense, they were heavy, but they weren’t necessarily dark. Most of the time I saw them, I thought they were well poised, balanced between the light and the dark – if they’d been totally dark they’d have been unlistenable. There was also something very exciting, this bright core to their music.

“Ian’s death was a shattering event. I don’t remember anything about mid-May 1980, it’s like a black hole in my memory. Part of writing the book was in some way laying this to rest and I found that at the end, I understood finally why Ian had done what he did. The main factor to me was the illness. He had epilepsy, seriously, it was a debilitating disease obviously made worse by the fact that he was in a really hot rock band which relied on his very intense performances, so he was pushing himself. The treatment for the illness, which was heavy duty tranquillisers or barbiturates, wasn’t helping either. So you’re a young person with this illness and you don’t know if you’re ever going to get better. I would think that would colour everything in a negative way. He was beginning to be unable to be the frontman of Joy Division and piecing this together I realised that there was a sharp downward turn which begins at the end of February 1980, at the Lyceum gig where he has a fit and after then the gigs get scrappy and he’s not well… it’s all coming apart at the seams. I went to see them on 11 April at the Factory, the last gig they did at the Factory, and I left before the end because it was too much.

“I know there are those naff bands like Interpol and Editors who took on the Joy Division sound… but his real influence was really the success of Joy Division making it clear that you could be in Manchester and be autonomous, you didn’t have to deal with the London music industry.”

THE NEXT GENERATION: TIM BURGESS, The Charlatans

“If something like what happened to Ian happened to a band today, it seems like the crossover of forming a new band just couldn’t happen, but they seemed to do it really well. They never lost their past, but they never stopped looking forward. The tragedy surrounding his death and the way he took his life, the way New Order became New Order, the photographs and the lyrics – everything around it is something you’d want to investigate, like a really great poet or author. And it was over so quickly, which made it more iconic. He’s a big figure, a literary figure, a musician and amazing frontman – if you put the jigsaw together it makes an incredible, powerful statement.

“The trench coat thing was an Ian Curtis thing and everyone walked round in trench coats in Manchester, but New Order then destroyed the trench coat. Everybody started wearing bright coloured T-shirts and went to the Hacienda. The Hacienda was Ian’s legacy in lots of ways because it was kind of financed by the work he put in.”

THE STUDENT: ORLANDO WEEKS, ex-Maccabees

“There was a moment when I was at university, at art school, and discovering Joy Division. I feel like it must still be a rite of passage for many people. In the early days of The Maccabees, when I was trying harder to be a better frontman, he was definitely one of the people I looked at, I was striving for that kind of abandon. If that’s not what you’re like and you watch that, you feel mesmerised by it. In the photos of him, it seems like there’s a very genuine sadness. There’s a sincerity to it.

“I remember reading Touching from a Distance by Deborah Curtis when I was 19 and it further confusing me, in the way it talks about Ian Curtis not as an enigmatic presence but a mundane presence, but also a very clever, thoughtful and invested one. You’re wanting to believe the legend, but also how absurd that is in the context of a very domestic experience. The toss-up of that, when you’re trying to believe you can get away with being in a band or writing songs that anybody might give a s*** about, it’s quite grounding.

“Maybe because Joy Division was so short-lived it didn’t go on long enough to undo its credibility. There is the enigma of it – there’s that footage of the robed monks all carrying great photographs of him, there’s a real showmanship in that.”

THE DESCENDANT: GRIAN CHATTEN, Fontaines DC

“I don’t try to emulate Ian but I’m aware that people perceive me as part of the lineage. We definitely went through a heavy Joy Division phase. They were incredibly good at painting pictures and what they had, which is something that all bands should strive for, is that they don’t waste a note and the message is pure in every one of their songs. They play the black writing against the white paper perfectly on every tune. ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ is a really obvious example of that. The music sounds like one of The Cure’s happier songs but heard far away and distilled. They were really good at putting a black pen to white paper.

“His bravery has made him an icon. To have that level of male sensitivity coming from a place like Manchester is already an evocative concept, and he managed to get people who liked to dance to listen to poetry. As a writer he was a facilitator for the unsaid. He was a great beacon of hope for people who secretly wanted to express themselves in a more romantic and emotional way. He completely destroyed any last shred of this machismo Seventies rock star and he made wearing the heart on the sleeve congruous to good art, good rock’n’roll music.”

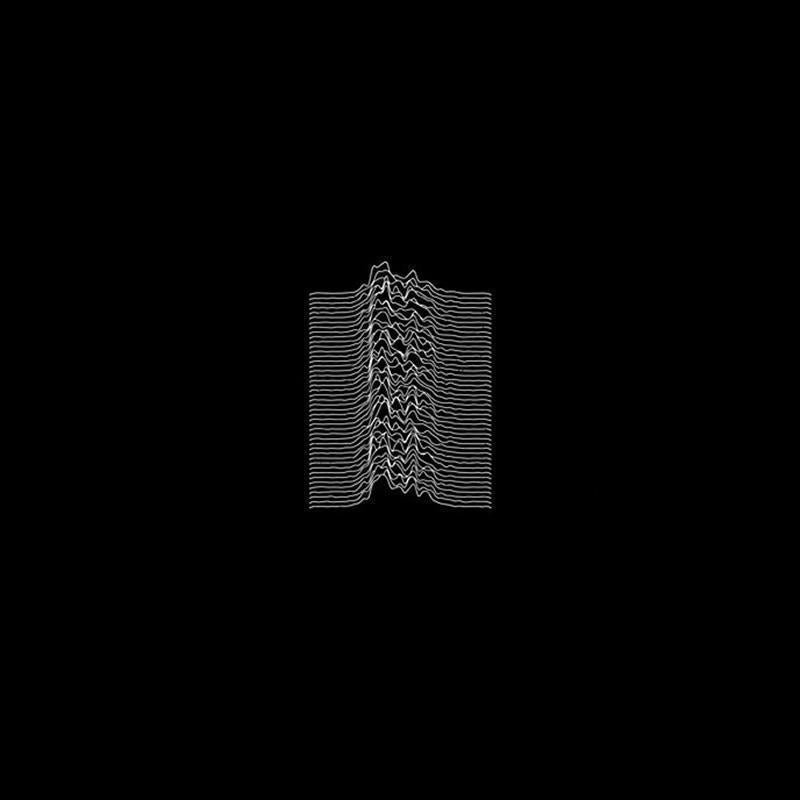

Joy Division’s album Closer will be reissued for its 40th anniversary on vinyl on 17 July, with three remastered non-album singles, “Transmission”, “Atmosphere” and “Love Will Tear Us Apart”. All on Warner Music.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments