Iceland's Hatari: 'At Eurovision, we're the pink elephant in the room'

Exclusive: As the cult Icelandic techno band prepare to destroy capitalism and storm Eurovision, Rob Holley meets them in Reykjavik for their first UK interview

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We’ve been described as a ‘bondage techno performance art group’, as ‘pseudo-fascist cyborgs’, as ‘IcePop’,” deadpans Matthias Haraldsson, one third of Icelandic art-school outfit Hatari. ”The list of descriptions is endless.”

His bandmate, mulleted-soprano Klemens Hannigan, chips in: “As soon as people start placing us within a genre, we instinctively react against that in trying to avoid a stamp. We started out with long hair and Mattias screeching, appealing to the metalhead scene. Our participation in Eurovision is yet another experiment.”

Hatari (translation: Haters) are a hyper self-aware, super-satirical and pointedly political BDSM trio, producing pounding techno-pop that sits somewhere between The Teaches of Peaches (2000) and Mortal Kombat: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (1995). And they fancy a shot at Eurovision glory.

Our interview takes place next to an athletics track in Laugardalsholl, an indoor sports arena on the outskirts of Reykjavik that is home to the national handball team, and was the setting for the World Chess Championship in 1972. A few days later, it doubles as a studio for the Songvakeppnin finals – Iceland’s preliminary Eurovision competition – at which Hatari will be announced as the winners.

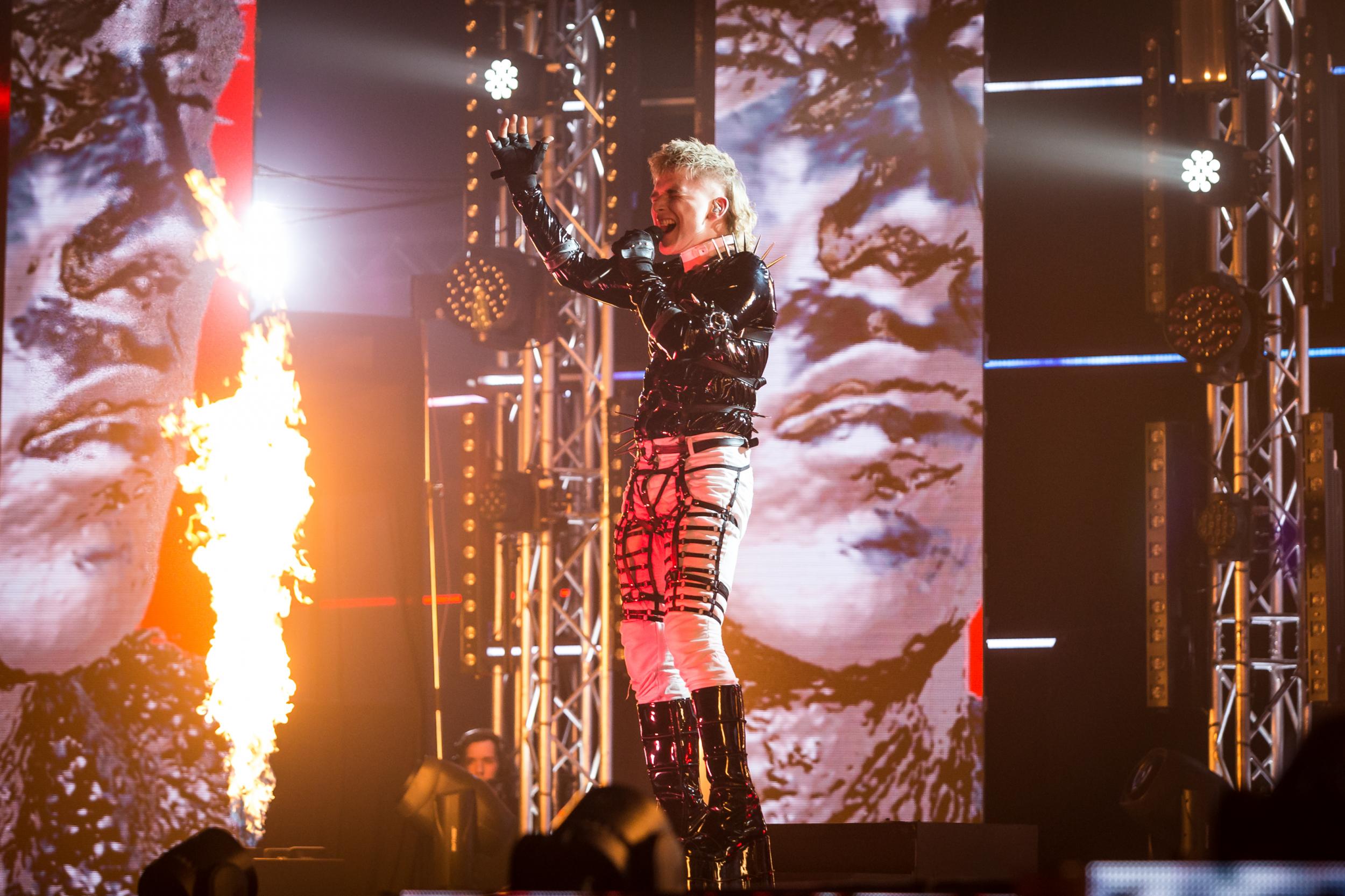

Hannigan turns up first. He’s wearing hot pink eyeshadow, knee-high platform boots and leather straps everywhere. He’s followed by his cousin and bandmate, Haraldsson, who is dressed top to toe in leather and spikes, with a full harness strapping down an off-white military jacket. If this sounds a bit much, it’s nothing compared to Einar Stefansson, the producer and rubber-encased human metronome, who completes the group.

“The music scene in Reykjavik is very small, so it’s easy to be noticed and everyone within the scene is our friends, or we know each other,” Hannigan says, joking that it was only recently that the group “sold out”. “We started in the grassroots but now the whole nation knows who we are.”

He’s right. Hatari have been gaining momentum and winning critical acclaim throughout their homeland, impressing Iceland Airwaves festival-goers with their cybernetic horror shows and anti-capitalist agenda. For Eurovision competitors, these guys aren’t the rejected talent show contestants favoured by the UK, or the polished pop stars off Sweden’s Melodifestivalen factory line: they’re the real deal. A band at the top of their game, having fun, setting their own tempo and competing in Eurovision purely for sport.

Klemen’s falsetto contrasts with Haraldsson’s combative barking over electro beats pulsing harder than a two-day hangover. Choreographed by Solbjort Siguroardottir, Andrean Sigurgeirsson and Astros Guojonsdottir, each live performance tells a story in the tradition of a nightmarish Icelandic fairytale, packed with no-nonsense warnings, zombie-puppetry and doomsday prophecies.

At the end of 2018, Hatari announced they would disband as they’d failed to accomplish their stated objective: to bring about the downfall of capitalism. Haraldsson explained that “bringing down capitalism was too much. It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. We still want to obliterate it,” he says, “but also maybe sell a few T-shirts along the way too.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

To the surprise of the Icelandic music press, the band “unretired” early this year with the announcement that they were gunning for Eurovision, with a new song called “Hatrio Mun Sigra” (“Hatred Will Prevail”). The song is a “warning from the future”, prophesying the downfall of Europe: “The revelry was unrestrained/The hangover is endless/Life is meaningless/The emptiness will get us all/Hatred will prevail/Europe will crumble.”

Cheery stuff, then, for the global competition that gave us Abba, Celine Dion and, last year, the “Fuego” lady, Eleni Foureira. “’Hatred Will Prevail’ is pop,” Hannigan insists. “I was Googling the music to ‘Waterloo’ – itself a song about war – and noticed we use the same semitone up in ‘Hatrio Mun Sigra’. It’s pop. We’ve also been brainstorming an Icelandic, Hatari-style cover version of ‘Euphoria’ [Loreen’s winning song from 2012].”

“We live for these contradictions,” Mattias says. “I’m masculine, Klemens is feminine; I’m repressed, Klemens is expressive; I’m hard, he’s soft; I scream, he sings; I’m stiff, he dances – we explore these contrasts.”

Will the rest of Europe get it? The last time Iceland sent a satirical creation, Silvia Night (a bratty, narcissistic, female drag queen, played by Agusta Eva Erlendsdottir) in 2006, the Greeks booed her, wider audiences didn’t get the joke, the juries panned her and she was ungraciously dumped out of the semi-finals. But Hatari feels different. Outside of the art-school bubble, the band resonates with a variety of audiences on three main counts, making them a potent contender for the ESC crown.

First, and perhaps most importantly, the music is actually good. The Neysluvara EP (now on Spotify) is as catchy as any dance music you’ll listen to this winter, and the videos and live shows are truly electric – it’s easy to get whipped up by the sheer energy of their output.

They have the additional bonus of the fact that everyone loves an outsider – especially at Eurovision. Hatari have managed to galvanise an army of weirdos, hipsters, homosexuals, grannies and, somewhat inexplicably, their biggest fanbase: Icelandic children. During Songvakeppnin rehearsals they had to be ushered away from the greenroom windows, because hundreds of tiny, excitable eight-year-olds were screaming each time they caught a glimpse of the band.

Finally, they talk frankly about the moral complexities of performing in Israel. An important topic for regular Icelanders, who in 2011 became the first western European nation to officially recognise Palestine as an independent state. And one that could potentially see them banned from the competition (Eurovision acts are forbidden from using their stage for political statements).

When Tel Aviv was announced as the Eurovision host city, nearly 20,000 citizens signed a petition asking the Icelandic national broadcasters to decline participation, arguing that taking part amounts to an endorsement of Israeli human rights violations against the Palestinian people. Many of the country’s household names publicly ruled out competing.

“Clearly there’s a huge distinction between the actions of the Israeli state as an institution, at which criticism is directed, and the Israeli people,” says Haraldsson, who goes on to describe what he sees as the paradox of Eurovision this year: “You sign up to a contract that says you’re not allowed to be political in the competition, but if anyone thinks they’re going to Tel Aviv without a political message they couldn’t be more wrong. It’s a paradox because all of the songs that make it to that stage will offend the sensibilities of many people by virtue of the context of where the contest is taking place, and the legitimate criticisms many people have.”

“So that in itself is a breach of the Eurovision rules. You can’t go to Tel Aviv and perform on that stage without breaking the rules of Eurovision. That goes for us and everyone else. And you can’t be completely silent about the situation, as the silence in itself is a massive political statement too.”

Hannigan is keen to show solidarity with fellow Icelandic artists that have chosen a different approach. “I understand why others have decided to boycott Eurovision this year and they are absolutely right to exercise that right,” he says.

“Because it’s in Israel,” Haraldsson jumps back in, “Hatari felt even more inclined to participate. Our impulse was that Hatari should go to Eurovision. We felt that the politics not only in Israel but in Europe, America, and the rest of the world currently fall very much within the purview of Hatari – a dystopian theatre piece reflecting violence, hatred and repression.”

Rather than boycott the song contest, Hatari have been playing a different game altogether; embracing the platform the competition has given them. In February, an anonymous Hatari spokesperson read a statement live on Rás 2 (the nation’s equivalent of BBC Radio 2) challenging the Israeli prime minister to a friendly bout of glima (Icelandic trouser-grip wrestling, of course) on the day of the Eurovision grand final in Magen David Square, Tel Aviv.

“[If we win] Hatari reserve the right to settle within your borders establishing the first ever Hatari-sponsored liberal BDSM colony on the Mediterranean coast. If prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu wins the glima, the Israeli government will be given full political and economic control of South-Icelandic Island municipality Vestmannaeyjar. Members of Hatari will ensure the successful removal of the islands current inhabitants.”

“Our power as court jesters is to evoke a discussion,” Haraldsson points out. “People can have their opinions about the quality of the Hatari performance, but it goes to show that the themes we bring to the stage are things that need exploring; people want the opportunity for dialogue. It’s a heated, emotional topic.”

Iceland hasn’t made it past the Eurovision semi-finals since 2014, and they are the only Nordic nation to not have won the competition. Will hatred prevail this year?

“Our message is a warning in uncovering the dystopia that is happening in Europe, in America, all over the world,” Mattias says, cracking a rare smile at the band’s after-party in Bio Paradis, Reykjavik’s only arthouse cinema, as they celebrate their triumph at Songvakeppnin. “We will win Eurovision 2019. As of now, things are going as planned. Songvakeppnin was another step in the downfall of capitalism and the unveiling of the scam that is everyday life. We are the pink elephant in the room.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments