Graceland: Soundtrack of our lives

When Paul Simon released Graceland in 1986, who would have thought his mixture of wistful pop and African sounds would endure across generations? Harriet Walker salutes a political and cultural classic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In August 1986, Paul Simon sang "every generation throws a hero up the pop charts" at the opening of his album Graceland. But what he couldn't have realised was that, for a generation whose popstars are downloaded and then die with the regularity of digital fruit flies, his African-influenced opus was to become a cultural touchstone, and would remain cherished 25 years on.

Simon's seventh studio album came after 1983's Hearts and Bones, a project dogged by controversy – supposedly a Simon and Garfunkel reunion, it was marred by arguments, and Simon eventually wiped Art Garfunkel's vocals from the recording entirely. Having captured the attention and affection of the nascent liberal intelligentsia in the Sixties (especially during 1967's summer of love), Simon had a reputation as one of the foremost pop-beatnik wordsmiths of his generation. But by the Eighties, his career was lagging.

Celebrating its quarter-century this summer, Graceland was the album that brought Simon back into the limelight. It topped the UK hit parade and made No 3 in the US Billboard chart, hanging in at No 6 for a further four months. It earned Simon a Grammy for Album of the Year in 1986, and for Record of the Year in 1987 for its title track; he was named Best International Solo Artist at the Brit Awards that year. "He is quite simply the best," declared the New York Times upon its release, describing Simon's lyrics as the "pop equivalents of Wallace Stevens poems".

Graceland is a record that explores the artist's sense of crisis, not only within Simon's own Upper West Side malaise but also as a series of rites of passage in his listeners' lives. The album – which weaves a story of love, divorce, the quest for spiritual succour and the inevitable onset of middle age with catchy melodies, innovative forays into "world music" and swoopingly lyrical highs and lows – became the soundtrack to a generation who were growing old alongside Simon, who remembered his folk-rock days at the side of Art Garfunkel and appreciated his dissection of the challenges they were all facing.

And it has become part of the collective consciousness among the children that were raised on it too. Cited as inspiration and covered by contemporary bands such as Vampire Weekend, Hot Chip and Grizzly Bear, Graceland has a place in pop culture unlike any other record. "Simon belongs as much to us as he does our folks," writes essayist Nell Boeschenstein. "Not our folks the way they were before we were born, but the way they were when we first knew them, as they were losing their edge and feeling maybe a little insecure."

Simon, however, does not seem to have lost his edge – a new album, So Beautiful or So What, released in April (with a release date of June) has propelled him back into the charts, with his highest position in 20 years. He is currently on tour, and will reach Britain in time to play Glastonbury in June; the new album has sold 68,000 copies and entered the US Billboard charts at No 4.

I was just over a year old when Graceland first came out 25 years ago. For me, family lore lives in every lyric, every note, every key change and every single beat. It was the soundtrack to every car journey of my youth; when I was two and a half, I was sick all over my mother's lap in a transit van near Lyme Regis, before standing up to join in with the chorus of "Diamonds on the Soles of her Shoes". One friend of mine recalls his mother putting the tape on to do the housework to, another remembers it fondly as the only record in his father's collection that wasn't Christian rock.

It may have lain dormant and dusty during those years in which I was too cool to be seen anywhere with my parents, but then it returned – as if it had never been away – when I reached my late teens, when my parents and I were friends and conspirators, rather than two different species.

And we all – my sisters, too - still knew the words, the ticks, the eminently imitable air-guitar, slap bass and soft-rock sax riffs. "It's a feel-good album," says Sasha Frere-Jones, culture editor at The Daily and a music critic for The New Yorker, who was 19 when Graceland was released. "And that may sound like denigration or a cliché, but Paul Simon does 'feel-good' very well – it's hard to be in a bad mood when you're listening to Graceland, even when it's dealing with complex and dark things. It's uplifting, but not in a cheesy way."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

That was the draw for the generation who bought Graceland fresh off the shelves in 1986. It existed within a realm of "easy-listening" that included the likes of Sade and Chris de Burgh, but came with the serious credentials of Simon's history as a recording artist, conceits and lyrical cleverness more readily associated with the metaphysical poets, and a weight of political Zeitgeist concealed within its catchy chords and choruses.

Simon's inspiration for the album came from a cassette tape given to him by a friend of "mbaqanga", a genre of South African music which derives from the Zulus. He quickly became interested in the tempos, rhythms and references that he heard within it, and set about blending it with his own rather more cultivated brand of acoustic rock. Working alongside South African musicians such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the Boyoyo Boys and Miriam Makeba, Simon collaborated with township artists to create and consolidate one of the first examples of "world music". There were many cynics at the time who cried colonial plagiarism, others who declared that Simon's work contravened the UN-imposed anti-Apartheid boycott of South Africa, but the artists featured were fully credited and many of them later signed lucrative Western record deals; they toured with Simon himself, and played at his 1988 African benefit concert in Harare. Ladysmith Black Mambazo later became recording artists in their own right and provided the soundtrack to several Heinz Baked Beans adverts.

"Paul Simon did for world music what Banksy did for graffiti," says film composer Christian Henson, who was 14 in 1986. "He taught us that not only was the world a rich cornucopia of different cultures, sound and melodies, but that these things are in flux. They're not just to be observed, zoo-like, but are actually there to be worked with, changed and influenced by."

And so Simon melded his own culture with the one he was discovering, mixing zydeco accordion with lyrics that speak of technological and scientific advancement in "Boy in the Bubble"; blending traditional American rhythm and blues with a characteristic South African walking tempo to shivering effect in the album's title track of pilgrimage and soul-searching; and juxtaposing the whooping and gossipy tones of The Gaza Sisters with the context of a sophisticated Manhattan cocktail party in "I Know What I Know".

"There was never any doubt that it was a fantastic record," says Sasha Frere-Jones. "There's no other album like it, so full of magical mistakes. You can't plan an album like this: that light voice, the dry humour. It's a happy and elegant record that is quick-moving and catchy. There was a lot of talk of African music in the pages of the Village Voice in those days; the way it percolated then was so different from now, but it was a great album – and it was only good for South African music."

"I think it was like someone opening a door to 'all this other stuff'," adds Christian Henson. "Whether it was simply a conveniently placed, Zeitgeist-y introduction to the paradigm shift in our attitudes to what has since become world music, or whether it was actually a trailblazer. The true genius of what Simon did was to demonstrate that music is universal. That to go and work in a foreign land wouldn't necessarily reap a patronising and difficult-to-digest experiment, but actually a remarkably accessible collection of pop tunes."

With the political backdrop now more an aspect of history than a cultural context, it is the songs themselves that endure. Their qualities range from the anthemic, in "You Can call Me Al", to the cathartic, in "Crazy Love, Vol. II". And yet each of them presents a perfect capsule of a lifestyle or mode of thinking. I have swayed to "Al" in the back of my parents' Volvo, at house parties in London – more recently, at a hip nightclub in Los Angeles, where the entire crowd of twentysomething ectomorphs went mad. I have cried to "Graceland" and danced on my own to "I Know What I Know" – until my sister came and joined me. I have used the phrase, "Don't I know you from the cinematographer's party?" in email subject lines just to check that prospective acquaintances have the right sphere of reference. And when I finally met a cinematographer, I told my dad, who quoted the next line of the couplet right back: "Well, who am I to blow against the wind?"

It's no surprise, given the mythological hold that this album has over the current generation, that modern artists refer to it again and again. New York indie band Vampire Weekend come in for regular comparisons to Simon for their marimba and ska-influenced guitar pop layered with middle-class "white guy" vocals. "The idea of listening to music that a lot of suburban yuppies listened to in 1986 may not be appealing," admits frontman Ezra Koenig, who at 24 was not even born when Graceland was released, "but the lyrics are totally surreal. It's not like Paul Simon just grabbed some African beats and kept on writing 'Bridge Over Troubled Water'."

Perhaps it is the conflagration of such extremes that we latterday yuppies are so enamoured of; for a globally-conscious generation entertained by "mashups", the layering and blending of two pre-recorded tracks to create an entirely new mix, what was seminal for Simon and our parents now fits perfectly into our aural reserves. "It's not easy," says Frere-Jones. "Mashups can be really, really annoying. Graceland shouldn't have worked – you could take out the parts and play them as straight Highlife [a genre of African music, combining Caribbean calypso and Liberian dagomba] or straight acoustic. It doesn't happen very often, but his voice works on it." There is, of course, the undeniable fact that people love nostalgia, especially when it inspires a Proustian recidivism straight back to childhood. Or perhaps it's because we don't really know how we're supposed to grow old – we're the first collection of pensioners who'll be listening to rap, grime and dubstep, at any rate – and both Simon's lyrics and our own memories of our parents have taught us that middle-age can be joyful in its germaneness.

"I think most people's parents bought it to play at Eighties dinner parties while they talked about Live Aid and Tom Wolfe novels over vol-au-vents and glasses of Babycham," says Tim Noakes, music editor of Dazed & Confused magazine, and seven-years-old in 1986. "It makes me think of long car journeys squashed in the back seat with my brothers. I hated it then, but I love it now. I guess I've grown to see what my parents loved about it."

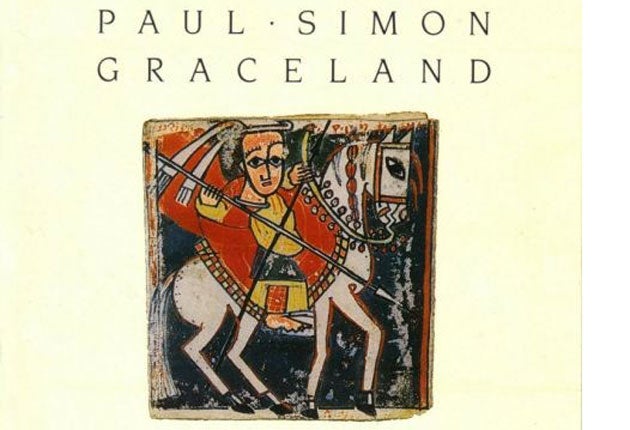

It isn't even about the music, so much as the album as an artefact. It was one of the first in my parents' collection to make the transition from tape to CD when the changeover happened, with its signature white cover, a medieval-esque illumination of an itinerant warrior stamped on the front.

"He's from the Bayeux tapestry," claims one friend confidently. "It's a political cartoon of Louis XVI," insists another.

I thought for years that it was a portrait of Paul Simon himself, despite the powdered wig. It's actually taken from the Langmuir manuscript at the Peabody Museum of Salem, but that doesn't matter – it's another part of the fable built up around Graceland, along with the countless children who thought the comedian Chevy Chase, who stars alongside Simon in the video to "You Can Call Me Al", was the gentle genius behind it all.

"The context of these things is often lost," says Christian Henson, "and I think we will forget how 'out there' Graceland was as a concept in its time. The way it will retain its hold on us all is the compositions. They are wonderful, wonderful tunes." And there is such glee in discovering the ubiquity of affection for them, a widespread love of something that you thought was just another example of your own family's weirdness. In the words of the album's final track "The Myth of Fingerprints": "This is not just me and not just you – this is all around the world."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments