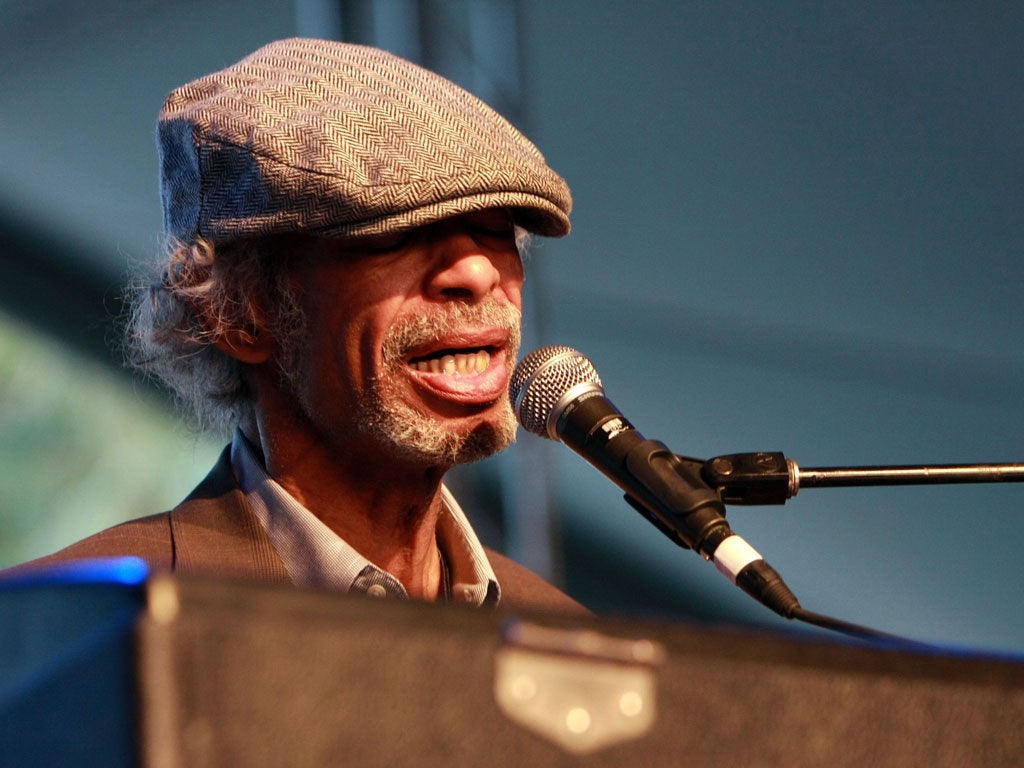

Godfather of rap's last words: Exclusive extract from Gil Scott-Heron’s posthumous memoir

Next month, the visionary poet, rap/hip-hop pioneer, and author Gil Scott-Heron will be honoured with a Special Merit Award at the Grammys. Here is an exclusive extract from his forthcoming memoir, The Last Holiday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I always doubt detailed recollections authors write about their childhoods. Maybe I am jealous that they retain such clarity of their long-agos while my own past seems only long gone. What helped me to retain some order was that by the age of 10 I was interested in writing. I wrote short stories. The problem was that I didn't know much about anything. And I didn't take photos or collect mementos. There were things I valued, but I thought they would always be there. And that I would.

There was Jackson, Tennessee. No matter where I went – to Chicago, New York, Alabama, Memphis, or even Puerto Rico in the summer of 1960 – I always knew I'd be coming back home to Jackson. It was where my grandmother and her husband had settled. It was where my mother and her brother and sisters were all born and grew up. It was where I was raised, in a house on South Cumberland Street that all of them called home, regardless of what they were doing and where they were doing it. They were the most important people in my life and this was their home. It was where I began to write, learned to play piano, and where I began to want to write songs.

Jackson was where I first heard music. It was what folks called "the blues". It was on the radio. It was on the jukeboxes. It was the music of Shannon Street in "Fight's Bottom" on Saturday night, when the music was loud and the bootleg whisky from Memphis flowed. The blues came from Memphis, too. Shannon Street was taboo at my house, something my grandmother didn't even think about. We never played the blues at home.

Our house was next door to Stevenson and Shaw's Funeral Home. The man who ran that business was Earl Shaw, one of the nicest men I've ever had the pleasure to meet. His wife was a good friend of my mother, and our families were so close that I related to his children as cousins for years.

Evidently business at the funeral home was good because I remember clearly when Mr Shaw purchased another building in East Jackson and the movers came to take everything out of the place next door. And then the men from the junkyard came to put everything else in the back of an old truck. My grandmother knew the junk man and after a brief conversation with him he directed his two sons to bring an ancient and well-used upright piano into our front room and push it up against the wall. I was seven years old. Old enough to start learning to play. What she had in mind was that I learn some hymns I'd be able to play for her sewing-circle meetings. That's how my music playing started.

There was no blues on the living-room radio. My grandmother had that one locked on the station that played her soap operas in the afternoon and her favourite radio programmes at night. When we got a second radio, it was quickly dubbed "the ballgame radio," and, sure enough, when a ballgame was being broadcast I listened. But at other times I'd try to tune in WDIA in Memphis, the first Black radio station in the country, with on-air personalities like Rufus and Carla Thomas and BB King. Late at night I'd try to get Randy's Record Show out of Nashville. I heard people talk about a music explosion in Memphis. I knew my favourite music, the blues, came from there, too. Memphis, Tennessee, was only 90 miles west of Jackson, my home. But Memphis was as far away as the North Pole in my mind. People in Jackson were always talking about somewhere else, mostly Memphis, because it was a close somewhere else and you could drink alcohol there, while Jackson was in a dry county. Some of my grandfather's relatives were in Memphis and I had visited them, but what I remember about the trip was getting car-sick and throwing up.

The history that we were given about Memphis was done in light pencil that hopscotched its way to a semi-solid landing with Elvis Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show... The city matured from midway market to a major metropolis... [from] saloons and whorehouse tents, once soaked with the sweat of drunken sailors and reeking with the acid stench of swine, slime, sewage, and slaves [to be] better known for Graceland and the Grizzlies than for Beale Street and the blues. Its filthy foundation as a headquarters for whores and for humans sold to the highest bidder was obscured by the magic of musical melding.

Sun Records considered itself the fuse that lit the 1950s with Elvis and rock'n'roll. With Carla and Rufus Thomas and Otis Redding, Stax Records brought blues to the hit parade with hooks and horns and a solid beat, evolving into Al Green and Willie Mitchell. Memphis meant music.

And unless you stop to think for a minute, you might forget that it was in Memphis that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr was shot and killed on a motel balcony on April 4, 1968.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Stevie Wonder did not forget.

In 1980, Stevie joined with the members of the Black Caucus in the United States Congress to speak out for the need to honour the day Dr King was born, to make his birthday a national holiday. The campaign began in earnest on Hallowe'en of 1980 in Houston, Texas, with Stevie's national tour supporting a new LP called Hotter than July, featuring the song "Happy Birthday", which advocated a holiday for Dr King. I arrived in Houston in the early afternoon to join the tour as the opening act. I was invited to do the first eight shows, covering two weeks, and I felt good about being there, about seeing Stevie and his crazy brother Calvin again.

I was tired already, sweaty and exhausted from a five-minute trudge uphill, learning as I trudged why this block-sized enclosure was called "the Summit". I had just found a stage entrance for a venue I had never played. The places I had played in Texas on prior trips could fit into this sprawling hothouse about 10 times and still leave room for the Rockets to play their games without me getting in their way. It was an impressive sight. Choreographed chaos on a Roman scale. But suddenly somebody called my name. Well, not exactly my name, but somebody's name for me, the name he always used, my astrological sign. So I knew who it was. It was somebody who shouldn't have seen me come in. Howzat?

The call for me rang out again, echoing around in the cavernous hall: "Air-rees!"

I scanned the upper reaches of the place, looking for Stevie Wonder.

And there he was, in a seat near the top row in the bowl-shaped theatre. He was leaning forward in my direction from the sound booth. Alone. There was no mistaking him. His corn rows were surrounded with a soft suede cover. Large, dark sunglasses hid most of the top half of his face, and a huge, joker's grin furnished the lower half. He had a wireless mike in his hand and, again with the grin, was saying, "Come on up here, Air-rees!"

I started for the stairs, still scanning. Now I could see there was an engineer-type person in the booth, but his back was turned to Stevie and I didn't believe I knew the man anyway. Or that he had identified me.

He hadn't. But since I hadn't figured it out yet and Stevie was having such a good time messing with my head...

"How you been, man," I said as I climbed. "If you saw me get outta that cab from the airport, you shoulda helped me pay for it."

"We felt your vibes, Air-rees," Stevie said, and he laughed out loud, shook his head, and held his hundred-watt smile.

I agreed to be on by 8.05 pm each night and to hit my last note no later than 9.05. That would give the humpers and stage muscle 25 to 30 minutes to change the sets for Stevie and [backing group] Wonderlove. Stevie's set would run the clock out, but at 11.30 or so he would call for back-up to do his last two numbers: "Master Blaster", the reggae-flavoured tune that included the line that was the title of his new LP, and "Happy Birthday", his tribute to Dr King.

The people producing the shows [were] worrying about us starting and stopping on time. I thought that was funny as hell, knowing that Bob Marley and the Wailers were coming in after two weeks. "Them brothers don't start rolling their show joints until they're 10 minutes late," I told [the stage manager]. "I'll be around an hour in advance."

I meant that. It lasted for about 24 hours.

Different dates on the tour were memorable for different reasons. Some days I took notes, though most of those notes seem to have been done as a joke, some kind of acrobatic way of pulling my own leg. There were either a few lines written before the show along with whatever expenses I needed to note, or, after the concert, in the early am, there was a separate page or two that described something that happened or that I felt during the day or evening. There was rarely both, rarely an occasion when I wrote something before and after a show. December 8, 1980 in Oakland was a before-and-after day. I still remember the after-feelings now.

I rarely missed things Stevie said to me. But when I saw him at the bottom of the backstage stairs at the arena in Oakland, I thought I must have misheard him. Maybe it was the shock at what he had said. Maybe I hadn't missed what he said and just thought I did. It was something I didn't want to hear.

But no, I must have mistaken Stevie for sure.

"What did you say?" I asked him, trying to get above the noise.

"I said some psycho, some crazy person, shot John Lennon!" Stevie said. "And I'm wondering how to handle it."

I am not so silly or naive as to suspect that there is an ultimate evil. But the death of a good man, so rare as to be nearly extinct, is a thorough tragedy. And what do you say about it to 17,000 people who have come out to see you and enjoy themselves?

I got that same feeling I'd felt when I heard that Dr King or someone else was killed; that sense of a certain part of you being drained away, a loss of self. There were certain events in your life that had such historical significance that you were supposed to remember the circumstances under which you received the news for the rest of your life. That was probably what some section of humanity used to illustrate man's superiority over other animals: "memories of miseries that memorialise."

Having those memories was like turning down the corner of a page in your life's book. But maybe animals turned down corners of pages, too. They might not choose the date of the death of John Lennon to see as a date of loss and mourning, they would be more likely to remember the date the Ringling Brothers died or the day the woman from Born Free was born.

I was sure they talked about important things. I didn't have the dialogue down pat, but I could picture a conversation between two lions on a late-night walk across the savannah.

"Yeah, that's where it was, man," one of them says. "Right over there by the watering hole. A big mean-looking thing with sharp teeth and the strongest grip you ever heard of. The gorilla called it an animal trap. Man, that thing grabbed Freddy Leopard and held him for hours. The gorilla got Freddy loose but his leg was all fucked up and he's still walking with a limp."

Just exactly what did those recollections, those dog-eared pages, prove? That you were connected to the human race? It couldn't be. Because if so, people born since then, who weren't around then, couldn't be connected. That's why there were history books and parents and other folks to tell you what happened before you got here.

And why did you need to remember those things? Most of them were about someone being killed or assassinated. You could almost feel as though you needed an alibi: "Where were you the day that such-and-such a person was murdered?" They were pages in history books, however. I didn't know why. I didn't know what it proved. That you were connected to the human race? They were usually the least human things you could imagine. Unnatural disasters.

I always knew where I'd been. I was in last period history class at DeWitt Clinton High School when the principal announced from the bottom of an empty barrel: "Ladies and gentlemen, I regret to inform you that your president is dead." He was talking about John Kennedy, shot to death by someone in Dallas.

I was in the little theatre at Lincoln when a guy everyone called "the Beast" had thrown open a rear door and shouted: "The Reverend Dr Martin Luther King has been shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee."

I was in my bedroom on West 17th Street when man first reached the Moon and I had written a poem called "Whitey on the Moon" that very night (for which my mother had come up with the punch line: "We're gonna send these doctor bills air-mail special to Whitey on the Moon").

And now I would always remember the night John Lennon died. Yeah, because of who told me and where, but also because of the effect the news had on the crowd. It proved we had been right, Stevie and I, when we hastily decided that it would serve no purpose to make that announcement before he played.

"No, just wait until the end, before we play them songs," I told him. "Hell, ain't nothin' they can do about it."

And that had been soon enough. The effect of Stevie's sombre announcement on the crowd was like a punch in the diaphragm, causing them to let out a spontaneous "whaaaa!". Then there was a second of silence, a missing sound, as if someone had covered their mouths with plastic, so tight not even their breathing could be detected. I was standing at the back of the stage, outside of the cylinder of light that surrounded Stevie, next to Carlos Santana and Rodney Franklin, who were joining us for the closing tunes.

Stevie had more to say than just the mere announcement that John Lennon had been shot and killed. For the next five minutes he spoke spontaneously about his friendship with John Lennon: how they'd met, when and where, what they had enjoyed together, and what kind of a man he'd felt Lennon was. That last one was the key, because it drew a line between what had happened in New York that day and what had happened on that motel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee, a dozen years before. And it drew a circle around the kind of men who stood up for both peace and change. That circle looked suspiciously like a fucking bull's-eye to me. It underlined the risks that such men took because of what all too often happened to them.

It was another stunning moment in an evening of already notable cold-water slaps, a raw reminder of how the world occasionally reached inside the cocoon that tours and studios and offices on West 57th Street provide. It stopped your heart for a beat and froze your lungs for a gasp; showing you how fragile your grip on life was and how many enemies you didn't know you had.

It also gave Stevie Wonder's tour and his quest for a national holiday for a man of peace more substance, more fundamental legitimacy. Not just to me. Everyone seemed to understand a little better where Stevie was coming from and what this campaign was all about:

It went from somewhere back down memory lane

To hey motherfuckers out there! There are still folks who are insane

In 1968 this crowd was eight to twelve years old

And they weren't Beatle maniacs but they did know rock and roll.

The politics of right and wrong make everything complicated

To a generation who's never had a leader assassinated

But suddenly it feels like '68 and as ar back as it seems

One man says "Imagine" and the other says "I have a dream."

Taken from 'The Last Holiday: A Memoir' by Gil Scott-Heron, published by Canongate on 16 January, £20. For audio, interviews and more information about Gil's Grammy, visit his channel on www.canongate.tv.

'Tribute to Gil Scott-Heron', featuring DJ sets from Gilles Peterson and Jamie XX and poetry from Kate Tempest and Ben Mellor; Wilton's Music Hall, London E1 (www.wiltons.org.uk) 19 January

© The estate of Gil Scott-Heron

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments