The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The Global Music Vault wants to preserve the world’s music in case of disaster – but how will they do it?

As the Doomsday Clock ticks even closer to midnight, Will Pritchard speaks to the people hoping to preserve centuries worth of music in a vault beneath the permafrost of Svalbard

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ten seconds is a long time when the clock you’re setting is ticking down to the end of the world. In January, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced that the Doomsday Clock – a symbol for how soon humanity can expect to meet its end as a result of our own unchecked advances – had ticked forward 10 seconds. We’re now only 90 seconds to midnight; the closest the minute hand has ever come to its final destination since the clock was unveiled in 1947.

It was news that arrived with stony faces and straight shoulders. While for some, the doomsday concept is dated by its associations with Cold War hysteria, the events apparently nudging humanity closer to its end – climate crisis, Covid, war in Ukraine – are anything but antiquated. And for those with an eye on preservation, the announcement has only served to steel their efforts.

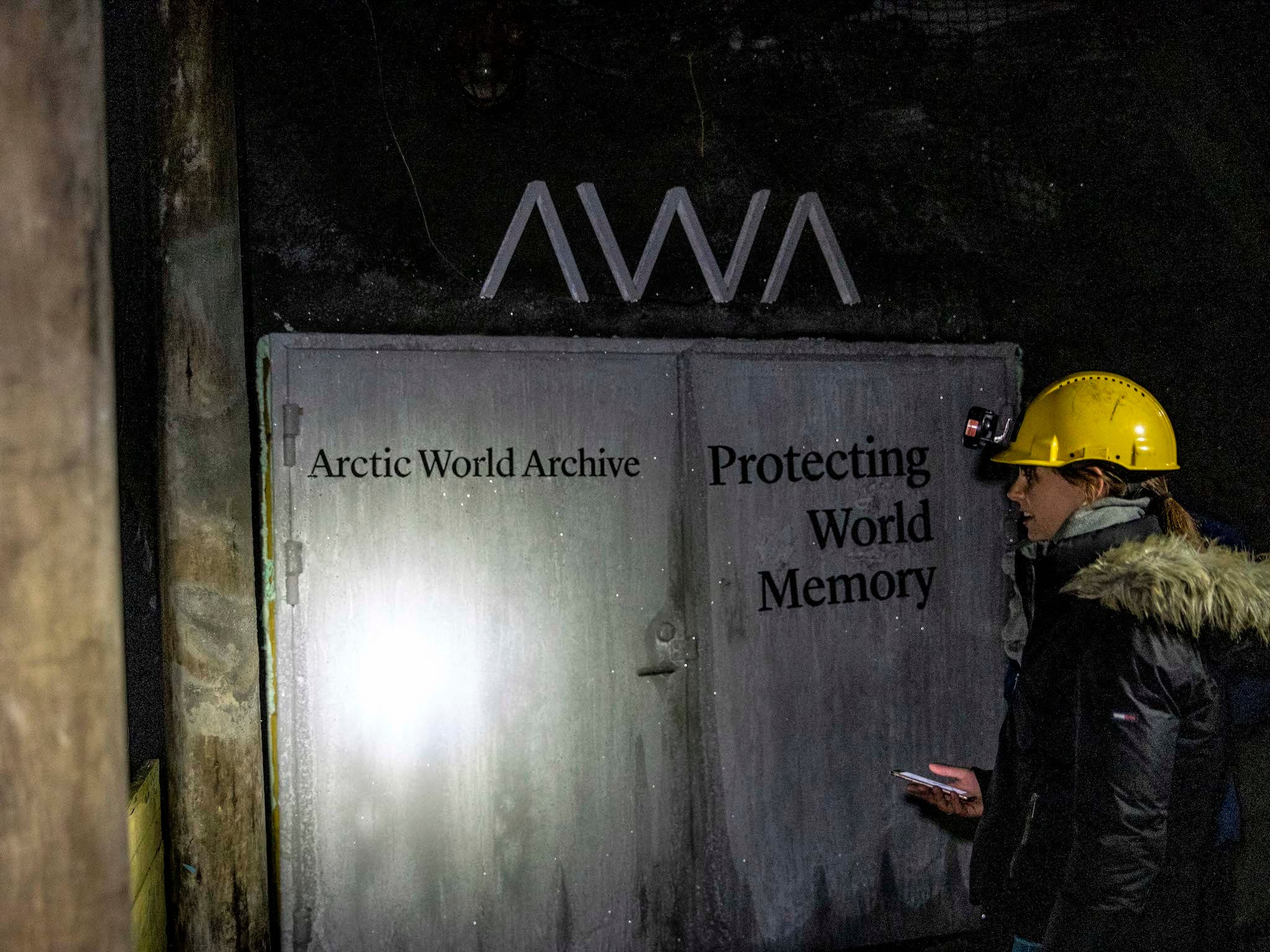

Roughly halfway between Norway and the North Pole lies Svalbard, a demilitarised Rorschach blot of rock where, for over a hundred years, coal has been cut from beneath the shelves of ice and snow. As those years have passed, and the mines have gradually shuttered, the spaces left behind have taken on new purposes. Some, such as the abandoned Soviet shafts of Pyramiden, have become tourist destinations. Others, meanwhile, have had their roles reversed: once places of excavation, they now offer storage. Most famous is the Global Seed Vault, behind whose striking, decorative facade lie millions of seed samples sourced from almost every country in the world. Then there’s the Arctic World Archive, which stores historical and cultural documents including Dante’s original Divine Comedy manuscript, 3D scans of the Taj Mahal mausoleum, and more on specially treated film reels, all locked behind steel doors stamped with the archive’s abiding slogan: protecting world memory. Now, a Norwegian company wants to add musical recordings to the vault beneath the permafrost.

When Luke Jenkinson, an Australian entrepreneur now living in Norway, saw what was being done with the Arctic World Archive and the Global Seed Vault, his mind went to something less tangible than food or even history. “I wanted to explore how we could do the same for music. How do we preserve all of this music that has shaped us for centuries?” he explains over the phone from Scandinavia. “The more I looked into it, the more I found that it was really just a checkbox for the music industry.” With this thought, the Global Music Vault began to take shape.

Time spent at Norway’s National Museum, as well as a stint in the music industry figuring out brand partnerships for globetrotting Norwegian DJ Alan Walker, gave Jenkinson a sense of both the opportunities and challenges posed. The issue was brought into sharper focus in 2019, when The New York Times Magazine revealed that a fire at Universal Studios 10 years earlier had destroyed as many as 175,000 master tapes belonging to Universal Music Group – and then been covered up. “Our job is to educate the music industry that this is not a nice-to-have,” says Jenkinson. “This is a must-have.”

It’s still not known exactly which masters were lost in the Universal Studios fire; this in itself is an indictment of the industry’s record-keeping standards. But the idea of a world in which future generations of fans and musicians might not hear Chuck Berry teasing out the first strains of rock’n’roll, or experience the outer reaches of John Coltrane’s wildly experimental Impulse! years, or come to know the era-defining acts of the modern age – the grain and emotion in Amy Winehouse’s jazzy tones, the searing poignancy of Alex Turner’s songbooks – feels difficult to countenance.

Other events have similarly hastened concerns. Jenkinson points to the plight of musicians fleeing Afghanistan following the Taliban’s 2021 takeover as another example that testifies to the fragility of living musical ecosystems, and how wars, along with freak accidents and natural disasters, can wipe out generations of accumulated cultural heritage.

The Global Music Vault (GMV) is a commercial bet, too, though. Jenkinson is managing director of Elire Group, a venture firm that is funding the GMV project in the hope of turning it into a profitable operation in the next five to 10 years. He watched closely as live music revenues shrunk during the Covid-19 pandemic and the market for established acts selling their song rights boomed, with investment funds and publishers like Hipgnosis and Primary Wave gobbling up the catalogues of everyone from Johnny Cash to Justin Bieber. These companies, Jenkinson is betting, will want to know their investments can be held safely – and be willing to pay for it. For that, he’s relying on the future.

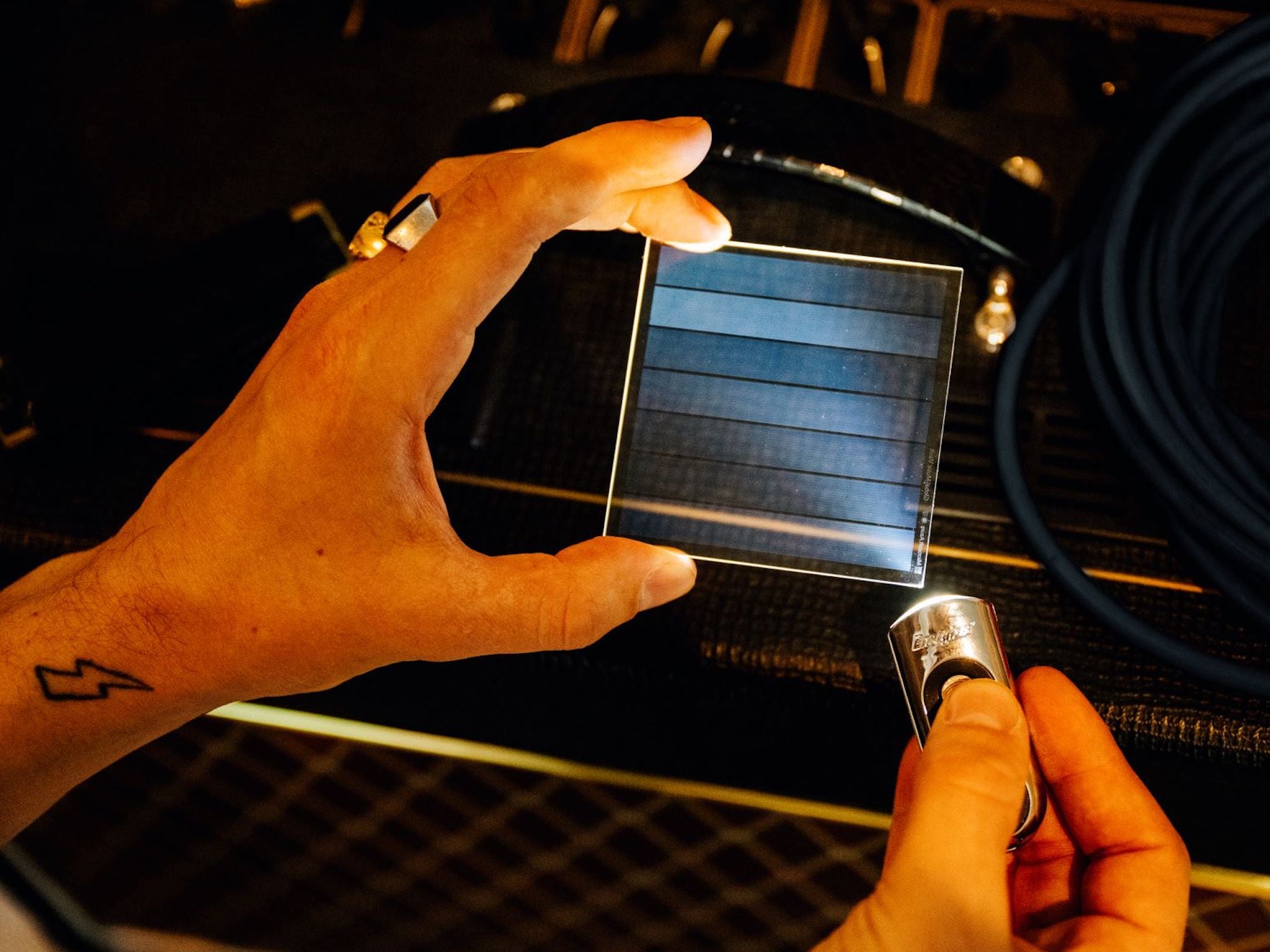

Elire has what Jenkinson describes as a “loose partnership” with Microsoft to use the Seattle giant’s emergent Project Silica technology in order to store the existing and ever-growing masses of music being produced (Spotify alone is reportedly homing as many as 100,000 new tracks every day). Project Silica promises storage that lasts “tens to hundreds of thousands of years”, with information cut by laser into CD case-sized squares of quartz glass. For Jenkinson, whose company aims to help businesses meet their environmental, social and governance commitments (a flourishing, sometimes problematic, area in the finance sector), the glass blocks hold an additional appeal. “We’re spending so much money and effort and power just trying to cool data centres globally,” he says. “And it’s just not sustainable. It is for maybe another 10 or 20 years, but then what happens?” A 2018 estimate put the annual energy use of data centres at 200 terawatt hours – more than the total energy consumption of some countries.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

But, in many ways, solving the technology problem and building the vault is the easy bit. The harder question might be deciding what goes in it. The first deposit to the vault is due to be made later this year, with contributions from Kenya’s Ketebul Music Archives, the Orchestra of Indigenous Instruments and New Technologies, and Lebanon’s Fayha Choir, among those earmarked for inclusion. Jenkinson wants the GMV to be defined by an open and far-reaching approach. “At the moment, those people that sit in libraries and archive roles, they’re the ones that decide, you know, what’s important and what’s not – and that’s normally in the moment or after what’s happened,” he says. “The music industry has a chance to remove those barriers of figuring out what should we archive, when, essentially, you can archive everything.” For now, while the project is in what Jenkinson calls the “sourcing phase”, he says, “we’re just calling out to the whole world, saying, ‘Find your most valuable music and start to digitise it with us.’”

This callout is being led by the International Music Council (IMC), which was established by Unesco in 1949 and today comprises 600 million members in more than 1,000 organisations across 150 of the world’s 195 countries. The IMC’s member network is vital to the GMV’s curation efforts, with responsibility effectively devolved from either Elire or the IMC itself down to the grassroots. The IMC’s current president is Alfons Karabuda, a composer, music rights campaigner, and passionate technologist, who spends a good chunk of our chat waxing on his belief in the possibilities of NFTs to transform how musicians are remunerated for their works.

Karabuda is interested in the potential of the GMV to provide decentralised access to the world’s riches of music. “It’s not about us being in an office in Paris deciding what is important in Myanmar or Zaire, that’s not the case.” Name-checking these places specifically, both of which remain in the midst of enormous political and social upheaval, feels deliberate. He points separately to the decimation of cultural heritage that took place during the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal rule over Cambodia in the 1970s, and to groups like Cambodian Living Arts who will collaborate with the vault to protect their precious materials. “The important thing for us is to highlight the importance of the heritage, and see what we can do to both promote and safeguard it,” says Karabuda. “But, of course, for it to be economically viable, the business model has to be both commercial and open to those who are not able to afford [to pay for storage space in the GMV].”

Altruism, like glass storage disks and renting mine shafts, comes at a cost. Both Jenkinson and Karabuda hope to find a solution that involves those more flush subsidising the people and organisations less able to stump up for storage costs. “This is nothing new for us,” says Karabuda, describing how contributions from better-off IMC members are used to cover subscription costs for those unable to pay but no less deserving of inclusion. Jenkinson is exploring options for UN funding, too. He mentions musical performing rights societies like PRS and PPL, which are responsible for collecting and doling out royalties to artists, as another possible source of money to support the vault. Mostly, though, Jenkinson is banking on the GMV’s technology being able to offer a more attractive alternative to the major labels’ current storage options. For now, Elire is footing the bill.

It’s not like you can ditch the market force side of things and be like, ‘I’m just going to save everything for free for everybody!’

There’s an inherent tension to this type of relationship between profit-seeking and cultural archivism. It’s a strain that should not be ignored, says Laurent Fintoni, a research fellow at the University of Bologna currently working on a digital library project. “You have to work through that tension,” he says. “You don’t pretend that it doesn’t exist.” Previously, Fintoni was involved with efforts to organise and preserve an archive of output from Red Bull’s long-running Music Academy project, which ran workshops, festivals and lectures with influential musicians in locations all over the world. Despite its underground influence, the academy was, in reality, a marketing scheme for the company – meaning that, when it stopped making sense for the drinks brand to keep funding it in 2019, regardless of the genuine cultural value of its outputs up to that point, those invested musically scrambled to save its legacy.

Similar efforts were spawned that same year, when MySpace wiped a generation’s worth of music from the internet after what it said was a botched server migration. The abiding lesson appears to be: don’t entrust culture to entities more concerned with making money than preserving memories. Still, says Fintoni, “it’s not like you can ditch the market force side of things and be like, ‘I’m just going to save everything for free for everybody!’”

Just as some people would have been fine having their teenaged sonic experiments wiped from the face of the web, Fintoni argues that the competing “archive everything!” approach has its dangers. “Traditional archival practices have, in the last 20-plus years, been challenged to confront their colonialist roots,” he explains, “by recognising that the way a white man may want to archive, say, the history of a native tribe in North America may not align with how this particular community likes to preserve its own history, right? Maybe they don’t believe in persistence in the way that the white man believes in persistence, for instance, maybe they believe that persistence exists through oral history, which means that it changes with every iteration of the story.” The answer, or one possible answer, Fintoni suggests, is to extend the involvement of those musical and grassroots communities in a way that goes beyond just picking what goes in – seeking to answer more searching questions of how things are preserved, and who should have access.

All of this only becomes more complicated when Jenkinson and Karabuda begin to expand on their vision for the vault to become something open and accessible – digitally, presumably, given where it’s located – to people all over the world. The music industry is still wrangling over how to handle streaming rights, and that’s without getting into the massive complexities of how to attribute (and remunerate) rights for indigenous recordings.

The Global Music Vault, then, is a seed of an idea that wants to grow, but currently has 1,000 feet of snow, ice, and rock to work through. Whether the project will deliver on its altruistic ambitions, or serve merely as the storefront for a new, laser-cut storage product, will only come clear as the freeze thaws. Whatever happens, the clock is ticking.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments