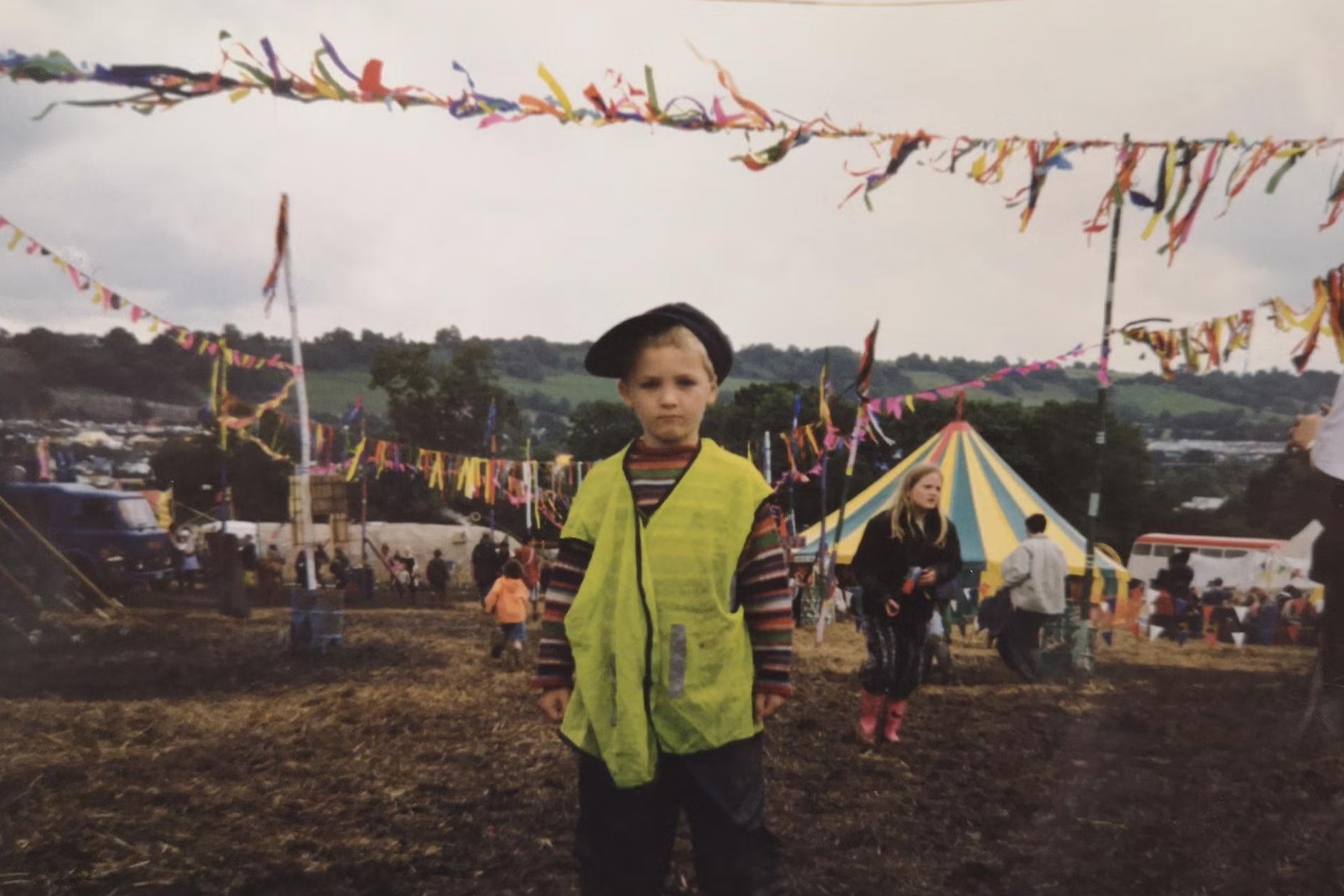

The earthy magic and lawless energy of being a child at Glastonbury festival

Adam White recalls the years he was more interested in seeing The Corrs than Courtney Love, and when the colours, noise and fire-breathing spiders gripped his imagination

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I wasn’t conceived at Glastonbury, but for the first decade of my life I may as well have been. I was, in many respects, a Glastonbury baby. Born and raised in nearby Bristol, I first visited in 1994, aged two with potty in hand, and attended for the five years that followed. I have not been back since. But even if Glastonbury has changed hugely in the decades in between, it still exists as a joyous, creative paradise of jugglers, acrobats and enormous fire-breathing spiders for those lucky enough to experience it as a child. Enough to grant it an almost mythical hold over many of the children who have passed through over the years, like a soothing imprinton the soul.

Back then, against the withering judgements of outraged co-workers, my parents saw it as an adventure and an education, for themselves and for me. My dad sometimes worked there as a steward, picking up litter and ushering in guests in exchange for a free ticket. But the tickets themselves were also relatively affordable – around £50 each, picked up from a local ticket shop, with under-12s getting in for free. Too broke to afford any sort of overseas holiday, Glastonbury was our version of an annual family sojourn, and a bargain considering what was on offer.

Music lovers and former punks, my parents felt at home there primarily for political reasons. As alien as it might appear today in the era of Wayne and Coleen Rooney arriving by private helicopter, Glastonbury was formally the main fundraiser for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and widely recognised as a space for anarchist bands and protest, both of which my parents were active in. To me, unaware of the anti-capitalist ethos that historically underpinned it all, it was mainly a land full of pretty colours and loud noises, a sensory dream factory that felt earthy and magical and escapist.

It was also terrifying. I was a nervous child at the best of times, but there was something in Glastonbury’s lawless energy that felt particularly disquieting, with every part of it somehow ripe with danger. I remember spending the entirety of REM’s headlining set in 1999 with my eyes locked on the chunky yellow lantern we had bought from Woolworths several weeks earlier, so sure that someone would come along and scoop it up. And that same paranoia permeated my time there over the years. It appeared whenever I ventured into the site’s long drop toilets, erected above enormous communal pits holding a festivals’ worth of human waste, with seats wide enough that I felt constantly at risk of falling in. And the tents in which we rested were natural incubators for childhood fear; I was certain that they would be unzipped and rifled through by maniacs, likely when we were sleeping. And that was only if they hadn’t been stolen altogether while we were out exploring. Every walk back from one stage or another was buoyed by a persistent feeling of dread. I’d be certain that we’d return to a gaping patch of grass where our makeshift home used to be, the tent having been pilfered by some imagined criminal hippie.

The irony of it all is that Glastonbury has long been safe for kids. Certainly it is now, having become about as dangerous as your average Hay Festival. But even 25 years ago and in the last gasps of its more unpredictable youth, where the only newspaper headlines Glastonbury regularly spawned involved criminality and overdoses, it was always strictly PG unless you went out of your way to look for the badness. And for the children there, many of us being exposed for the first time to alternative lifestyles or individuals under the influence, it served as an unparalleled education.

Freelance arts worker and PhD student Megan Vaughan regularly went to Glastonbury with her dad throughout the Nineties, and remembers a specific moment from one of their first trips there. “It started raining one afternoon and everyone obviously ran for shelter under the nearest tree or marquee,” she recalls. “But there were a group of people who stayed dancing in the rain outside a burger van, and I remember my dad stopping me and pointing out that those people were “on drugs”.

My parents skipped this really big band they loved so that 12-year-old me could see Jessie J

“I threw more awkward questions at him in those four days every summer than at any other time in his life as a father. I was hearing new terminology for different kinds of drugs, new swear words and new sexual references – I had certainly never encountered anything like that back in Macclesfield. I guess I was very lucky that I had a cool dad who was ready to answer those difficult questions in an adult way for me.”

One of the odd side effects of the Glastonbury experience for a child is that sudden dissolving of shame, where sights or words that we recognise, consciously or not, as “adult things” suddenly become less frightening or at least OK to be talked about. It’s likely a product of so much forced intimacy – we’ve already seen each other caked in mud, and heard the neighbours in the next-door tent make noises that no four-year-old should ever hear, so what difference would an awkward question make?

And it applies to the music, too. The acts I have vivid memories of seeing as a kid are often of the more commercial Top of the Pops variety, purely because those were the big pop anthems I unashamedly loved as a kid. I have absolutely no memory of seeing Johnny Cash on the Pyramid Stage in 1994, which my mum always insists that I witnessed, but I sure as hell remember sitting on my dad’s shoulders while Heather Small sang “Moving on Up” the day before. And while any self-respecting six-year-old can lose their minds to Hole’s “Celebrity Skin” and I might tell people that my highlight of 1999’s festival was seeing Hollywood-glam-phase Courtney Love sing “Malibu” while Melissa Auf der Maur wafted away behind her, I can’t deny that I was mostly hyped for The Corrs that year. But being a child at Glastonbury also means a brilliant absence of good taste, with no awareness of what it means to be cool or the importance of being seen at the right places.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

“We used to print off a clash list and highlight what we all wanted to see and compare what sacrifices we had to make,” recalls film journalist Millicent Thomas, who went to Glastonbury three times with her parents between the ages of 11 and 13. “Because obviously they couldn’t let me just go off and see the bands I wanted to see. I can’t remember who it was they skipped, but I remember they were really gutted about it because they skipped this really big band they loved so that 12-year-old me could see Jessie J. I feel so bad looking back on it.”

Most of all, childhood is the best way to spot just how transformative Glastonbury can be, its excess and noise not only creating a vast new world unlike anything you’ve seen before, but shifting how you see yourself.

Glastonbury threw me into a state somewhere between childhood and adulthood. I had never felt more young, nor more aware of my physical size, but I also remember feeling oddly defiant and assertive. Glastonbury was terrifying in its loose recklessness, but not so much that I didn’t feel like it could bend to my will if I thought hard enough. Here was a space where typical rules didn’t apply, where my parents wouldn’t be as firm or as protective as they were at home, I thought. I recall being genuinely hurt that they refused to let me see Scream 2 at the festival’s cinema tent in 1998, as if merely being at Glastonbury meant it would be OK for a six-year-old to watch.

And it’s a strange power that feeds into why I’m in no rush to go back. Those years were so formative that the idea of returning would feel like the worst kind of nostalgia, with its inevitable disappointment and awareness of the changes that have occurred. And where once speculation that Kate Moss had been spotted walking around the campground was written off as an unlikely rumour, the festival is now so bombarded with celebrities, gourmet food trucks and luxury tents that there’s little chance of it feeling the same.

Millicent agrees. “I can’t see myself wanting to go again,” she says. “There are different kinds of crowds that go now, and it’s got a lot bigger – I just don’t think I could manage it. I think I’d be very anxious there now.”

But Glastonbury still lingers in other ways, regardless of how alien it is to me today. I still get a nostalgic rush from seeing a truly pitch-black night sky unburdened by street lights or buildings, throwing me back to seeing it for the first time in Pilton, and the acts I remember enjoying back then are still in semi-regular rotation on my phone. And that includes, with zero shame, The Corrs.

Megan has gone back with friends as an adult, her trips with her dad brought to a close after a year in which she “got off with a teenage boy a couple of years older than me on the second day and then completely disappeared”. But how it’s changed in the interim or whether she’s physically there every year are also largely irrelevant, with Glastonbury long having seeped into her everyday life.

“I work in the most experimental edges of fringe performance now,” she explains, “and I can absolutely see that the things that I was discovering at Glastonbury in those theatre and circus fields, or the late-night cabaret stuff or the weird X-rated spoken word, and all the weird subcultural, surreal visuals in those performance areas, all informed my taste as an adult but also my career. It was totally an appetite that I developed when I was a kid there.”

For a few years as a teenager, I was sure that I might have imagined my time at Glastonbury, existing as it did in arbitrary images or strange flashes, while our photo albums laid untouched for a decade. But found buried at the bottom of an old suitcase, when I was 20 or so, was a child-sized T-shirt from Glastonbury 1999, the festival’s logo on the front and that year’s line-up printed on the back. It was partly infuriating, decorated in the names of bands I love today that I could have seen then but didn’t. But it was heartwarming most of all, a physical object confirming what an unusually exciting time I had for a few summers when I was barely a person. I no longer understand how I could have ever fit inside of it, but it brings me unparalleled joy knowing for a fact that I once did.

This piece was originally published in June 2019

Glastonbury 2023 is held from Wednesday 21 June to Sunday 25 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments