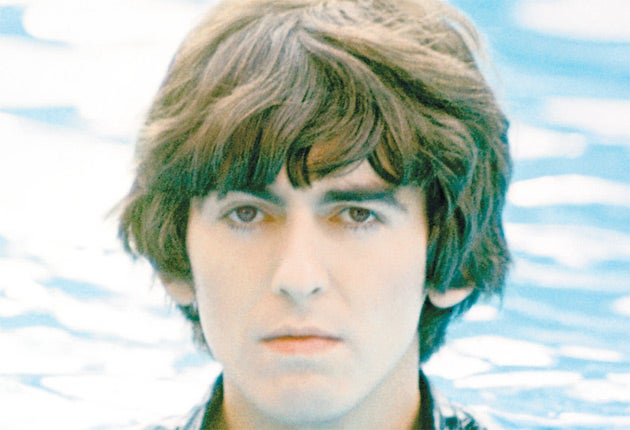

George Harrison - Something in the way he moved us

As Martin Scorsese's portrait of George Harrison is released, celebrated novelist Paul Theroux looks at the man who went from mop-top to mystic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a happy thought that the sweetest music arises from an untroubled heart. As though from the sky, here is this strong and contented virtuoso – George Harrison, say – whom we envy for being strong, someone supremely contented. What a lucky man to be able to create such harmony and to penetrate our soul; to make us feel better, to help heal us and ease our minds. Isn't it pretty to think so?

The truth is usually the opposite of this. The art that is indestructible and always fresh never comes easy. Its source is typically uncertain or bleak, sometimes harrowing, the pure notes quavering over an abyss of shadows between life and death, that mournful place from which the most passionate yearnings take shape in the form of a song, a poem, a story, a harmonious vision. But even as I write this, speaking of the complex process of creation, words and music made of doubt and the divided self, the conflicts that help us to be sane, and the paradox of opposites, I seem to hear someone mutter over my shoulder, "Rock music is about as metaphysical as my Aunt Fanny..."

And yet it seems to me impossible to overestimate the resonant clarity of George Harrison's music – his songs of innocence and experience; or the subtle wisdom of his lyrics. Even as a relative youngster, more than 30 years before his untimely death, in his All Things Must Pass album, he was singing powerfully of transformation, in the title track, and "Art of Dying," and "Beware of Darkness," and "What is Life." He could be as jolly as his ukulele-strumming hero and namesake, George Formby, but as soon as he seizes our attention with his humour and his teasing, he is reminding us – and himself – that we are mortal and all things end.

George at his best was a man dedicated to whittling down his ego; he was not one being but many and he remains an enduring figure of fascination to those of us for whom his music runs through our head, reminding us of better times. It is no wonder he was so passionate: he was himself his own wicked twin. He made no bones about this and, a hater of pomposity in all forms, he expressed it with characteristic downright-ness:

"I have this kind of strange thing," he said, "and I put it down to being a Pisces. Pisces is the sign of two fish. The way I see it is that one half is going where the other half has just been. I was in the West and I was into rock'n'roll, getting crazy, staying up all night and doing whatever was supposed to be the wrong things. That's in conflict with all the right things, which is what I learned through India – like getting up early, going to bed early, taking care of yourself and having some sort of spiritual quality to your life. I've always had this conflict."

He was at odds with himself, but who isn't? In that respect "living proof of all life's contradictions," as he put it, he resembles most of us. We recognise him as a kindred soul in his contradictions – and though his life was lived on a vast scale, he was unusually truthful, and in his songs much more explicit than we dare to be. He made it his mission to explore his contradictions in his own way, through his music. So, to say that he was one of the great musicians of his time –one of the most innovative guitarists ever, most imaginative songwriters – is to give only part of the story. "The quiet one," is the stereotypical description of the man – but he was on fire within. To make music that mattered over the years, to bring renewal with each work, he seemed determined to burn out one self after another.

"He had karma to work out," his widow, Olivia, is on the record as saying. "He wasn't going come back and be bad. He was going to be good and bad and loving and angry and everything all at once. You know, if someone said to you, 'okay, you can go through your life and you can have everything in five lifetimes, or you can have a really intense one and have it in one, and then you can go and be liberated,' he would have said, 'give me the one, I'm not coming back here.'"

I also think there's a stark difference between "contradiction" and "confusion". He wasn't confused; had he been he would have found it impossible to search and learn with such clear-sightedness. His friend and mentor Ravi Shankar said that George exhibited tyagi, a Sanskrit term for a feeling of non-attachment or renunciation. Shankar wondered how this aspect of enlightenment could have come so clearly to a worldly lad from Liverpool. It doesn't seem odd to me that this thoughtful man came to feel the sense of freedom bordering on exaltation that mendicants experience in non-attachment. But it is a notable, and noble, quality in a rock star to practice it, as George did.

We all feel that we could do a bit better in our lives; in the secret history of this imaginative soul, George was active in pursuing this path. Surely it arose in large part from his having had everything while still young. At 19 or 20 he was on top of the world – inspiring the world to sing and dance. Performing with The Beatles gave him joy – gave us all joy. But he did not see this exuberance as a final fulfilment; the very fact of The Beatles as a musical and financial phenomenon made him doubtful enough to begin to look for a higher meaning, and – after The Beatles – to go on looking. He knew he was living in the material world, but had he been so attached to it he would not have been able to look deeper into it.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Early in his life as a musician, towards the end of the explosive new sound of The Beatles (and much more than music, it was a seismic shift in popular culture), George found his way to India. Through music and meditation, and the mantras that he chanted until the very end of his life, he was drawn to an unselfish, and ultimately a more mystical view of the world. The man who could make a whole stadium rock began to see silence as another ideal. He has described himself as an idle, smirking, doodling student at school, and yet in India he became devout and studious, a reader of the swamis – and notably, of Swami Vivekananda.

What has become apparent in the decade since his death is the uncanny symmetry of George's life – a life lived to the fullest. What might have seemed random or impulsive in him while he lived, is, in retrospect, a pattern, part performance, part pilgrimage.

His saturation in the material world drove him to seek the spirit in things – and so his life seems a series of vanishings and reappearances, journeys there and back, and even the portraits of him that seem iconic are various, a progression of so many faces, his features, his hair, his posture – different in each one. Yet his gaze is unchanged, his eyes telling us that the same soul is inhabiting this body.

All this sounds solemn, but he was a man of subtle and often self-mocking humour. George was interested in many things beside music, and although music was his first love, he was vitalised by travel, movie-making, and car racing. Look at his friends – the Pythons Gilliam and Idle, Jackie Stewart, Billy Preston, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Ravi Shankar: the funniest men on Earth, the fastest, his most brilliant contemporaries in music.

But equal to his passion for music, and his diverse and close friendships, was an overwhelming desire to get back to earth – literally so, to dig, to plant trees, to surround himself with flowers that he himself had grown. The most obvious characteristic of the houses that he built, or bought and fixed up in the course of his life, are the gardens he planned and planted. No matter how extraordinary the houses, the gardens he created around them surpassed the bricks and mortar. In George's case the gardens he made gave him the sense that he was living in isolation, on an island of his own making. "...it's great when I'm in my garden, but the minute I go out the gate I think: 'What the hell am I doing here?'"

"From the day I met him he was defiant," Olivia said, "and so determined that nothing was going to stop him from leaping as far as he could."

She was thinking of his words in the song "Run of the Mill": "How high will you leap?/ Will you make enough for you to reap it?/ Only you'll arrive – at your own made end/ With no one but yourself to be offended/ It's you that decides."

'George Harrison: Living in the Material World', by Olivia Harrison, edited by Mark Holborn, is published by Abrams on 3 October; the film will be out in cenmas for one night only on 4 October and the DVD is out on 10 October. Paul Theroux's latest book, 'The Tao of Travel', is published by Hamish Hamilton © Paul Theroux, 2011

Review: George Harrison: Living In The Material World (3/5)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

This lengthy and hagiographic portrayal of former Beatle George Harrison (who died in 2001) can't help but seem slightly anti-climactic by comparison with Scorsese's magnificent earlier documentaries and music films (most notably his Bob Dylan film 'No Direction Home'.) It also has a lop-sided feel. The first half, dealing with Harrison's Beatles years, is riveting. The second half, exploring its subject's mysticism, his involvement in HandMade Films and his later music ventures, such as The Traveling Wilburys, is markedly less gripping.

Scorsese and his team assemble their archive material (much of it never seen before) in virtuoso fashion. Early sequences exploring the Beatles' time in Hamburg will make essential viewing for all Beatles enthusiasts.

The brilliance of his songwriting notwithstanding, Harrison never escaped from his reputation as the quietest and most inscrutable of The Beatles. Scorsese's documentary makes us warm to his personality and talent without quite prising him out of the shadow that Lennon and McCartney still cast over him and his career after all these years.

Geoffrey Macnab

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments