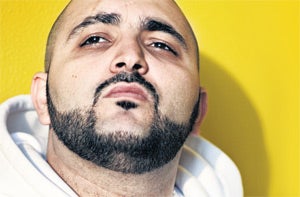

Eslam Jawaad - Preaching to the unconverted

The failed sale of a mammoth tusk changed Eslam Jawaad's life. Now, as Nick Hasted discovers, the rapper has higher aspirations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The double-take from a waitress as Eslam Jawaad talks in an east London bar is understandable. This hefty, deep-voiced Syrian-Lebanese man is discussing how his life hinged on the day he almost sold a Siberian mammoth tusk. That was the end of his happy times hanging out with the Beirut mafia and the beginning of a harder life as an Arabic rapper in the UK, with a bit of help from Damon Albarn, De La Soul and the Wu-Tang Clan, all of whom are present on his debut album, The Mammoth Tusk.

"I was young, and to me that world was fascinating," Jawaad (whose real name is Wissam Khodur) tells me. "I was drawn into it by gangster music and movies. I also have a revolutionary character, and I felt the mafia was against the government. But then I realised a lot of countries that seem at war with each other do business through their mafias. The biggest client for drugs through Lebanon is Israel.

"They do a lot of dark and sinister stuff and hurt a lot of people as well," he concedes. "They're a business, and they somehow justify that. I don't think they want to hurt anybody. But obviously, they will."

Jawaad was taken under the wing of the then-head of Beirut's drug trade. "At times I felt like, 'Dude, this guy could just shoot me,'" he laughs. "He did want me to become his main distributor in Beirut for heroin. A position I turned down because, ironically, I was opposed to hard drugs. I was more interested in other areas, like counterfeit money – or mammoth tusks..."

Jawaad's part in a prehistoric tusk's journey from a Siberian excavation, via thieving Russian mobsters and a Dubai businessman, to the Syrians who approached him to finally dispose of it for a $100,000 cut he secretly arranged to increase by $1.5m, is largely told on The Mammoth Tusk's title track. But though this incredible tale shames most gangsta-rap fantasies, the song sounds like sensuous R&B. It's the sound of a pressured man half-asleep, numbed by "cocaine and Benzedrine" as he drifts to his fate.

"I was pressured, I was scared," he admits. "I was half-asleep in that I was stupid enough to talk to mobsters. When I woke up in the morning and that deal fell through" – parties he wishes to leave off-record left him tusk-less – "that snapped me out of it. The mammoth tusk was life-changing because it fell through. Otherwise, I would have pursued a career in crime."

Jawaad came to the UK in 2003 to follow a healthier passion: Arabic hip-hop. But temptations lingered. "Drug-dealing is a temptation," he admits. "Other stuff, no. It's nostalgic when I meet people in that world. I don't agree with that lifestyle. I'm lucky I'm not dead. But it has a nostalgic feel, definitely."

Jawaad mostly comes across as practised and professional. But the lid he's put on harsher, politically risky feelings keeps bubbling off. "Criminuhl", on the new album, suggests why, detailing the day the police stopped and searched him three times. "The third time, I got jumped by about six officers, smashed on the ground, handcuffed and racially insulted," he recalls. "People were clapping, like: 'We got one! A real-life terrorist!'

"That atmosphere's spurred the Islamic hip-hop movement in the UK," he continues. "Don't get me wrong, I love the freedoms I get in England. But 'Criminuhl' is about the way you can say anything you want about pimping, drug-selling, shooting people on an album. Politicians can say what they want. But if you say something Islamic, you're going to get treated like a criminal. I don't say whatever I want, because it'll be interpreted wrong."

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

British music proved a happier experience. Asian Dub Foundation shared Jawaad's "revolutionary thinking", and the Moroccan Wu-Tang affiliate Cilvaringz put him on a tour by the Clan's Killa Beez. Damon Albarn used him on a track by the Good, the Bad and the Queen, "Mr. Whippy", and on their tour. "Growing up with a lot of racism, you get put off white people, sometimes! But Damon to me represents the good nature of white Britain. We're both on that mission, to teach our side through music."

It's Jawaad's unique perspective, not the shaggy-elephant story his life became, that makes The Mammoth Tusk rewarding. "My English rapping compromises, it's straightforward," he explains. "The way I present messages is shallow-sounding because I want to reach people in clubs, not the converted. 'Trick' sounds like some pimp song. But the [anti-sexual exploitation] lyrics are blatantly not that."

It's the album's deeper parables and metaphors, and Arabic tracks (including the Albarn collaboration "Alarm Chord"), that make it stand out. "The Koran speaks in parables, and I use a lot of verses from it in my own words, in English," he agrees. "It enriches the rapping. My Arabic rapping is more powerful to me than English. I use classical Arabic from the Koran, a very strong and commanding language."

Jawaad's most lasting influence is his grandfather, a Syrian revolutionary in French colonial days. "He passed values down, as I want to. I want to make money from music, to research alternatives to money, and educate as many as I can. I don't just want to inspire people. I want to go out and help."

'The Mammoth Tusk' is out now on Eslamophobic Music

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments