Playing it safe: How music documentaries are often hagiographies

Lili Fini Zanuck’s ‘Eric Clapton – Life in 12 Bars’ and Julien Temple’s ‘Suggs: My Life Story’, about the Madness frontman, are released later this month, but are these music documentaries airbrushing out the uncomfortable stuff?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Claims of sexual harassment are still engulfing the film industry, the theatre world and the House of Commons, but the music business remains relatively unscathed. It’s not surprising as the music industry has always been extremely efficient at protecting its own, especially when it comes to music documentaries. The majority of films made about major recording artists still living are straightforward hagiographies that heap praise on the given subject. If the musician is dead, the documentary tends to be bolder, as with Asif Kapadia’s grimly exploitative Amy, Brett Morgan’s similarly prurient Cobain: Montage of Heck, about the Nirvana frontman, and Nick Broomfield’s terribly sad Can I Be Me about Whitney Houston.

The latest two music documentaries on release this month are Lili Fini Zanuck’s absorbing Eric Clapton – Life in 12 Bars and Julien Temple’s charming Suggs: My Life Story, about the Madness frontman.

The former film charts the lauded Surrey-born guitarist’s miserable relationship with his mother, his fixation on George Harrison’s wife, Pattie Boyd, his obvious love of the blues and his alcoholism and drug use. Does it also touch upon his most unpleasant moment? Well, it has to. At a concert in Birmingham in 1976 Clapton evoked Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech, informing a confused crowd that England had “become overcrowded” and that they should vote for Powell to stop Britain becoming “a black colony”, before going on to say, “get the foreigners out, get the wogs, get the coons”, and repeatedly shouting the National Front slogan “Keep Britain White”.

On the voiceover to Life in 12 Bars, Clapton does sound genuinely apologetic and horrified by his unsavoury behaviour – “I was becoming chauvinistic and fascist, too,” he admits – but lays the blame on his heavy alcohol consumption. At the time his comments famously sparked the Rock Against Racism movement and there was a lot of anger, but his booze-fuelled bigotry is pretty much forgotten (even forgiven?) now. It would have helped his cause if he’d not only apologised to camera in 12 Bars but also showed some contrition throughout the years. However, that doesn’t feel like the case and in 2007 he even managed to reemphasise his support for Enoch Powell on The South Bank Show: “I was convinced that we had a weird kind of attitude – the government’s attitude – towards immigration, [which] was corrupt and hypocritical and my impression of Enoch Powell was he was somehow telling the truth and was predicting there would be trouble and, of course, there was and is…”

Zanuck’s hagiography doesn’t dwell on the issue for too long, which really seems like a standard practice for music documentaries; in the main they tend to airbrush out the uncomfortable stuff.

Temple’s My Life Story is a much wittier and more endearing affair – much like its subject matter – in which Graham “Suggs” McPherson is hugely (probably deservedly) indulged. The 56-year-old “national treasure” (he’s played on the Buckingham Palace roof, after all) performs a sort of stand-up routine, detailing his life, for a small, receptive (and suspiciously attractive) gathering in Wilton’s Music Hall in east London. The Madness singer riffs on his eventful life with typical sass and eccentricity. There’s zero chance of contradiction here, however, as Suggs is the sole narrator of the piece and we have to take his teenage escapades and scrapes (bar brawls, spray painting walls, trouble on Chelsea’s football terraces) in 1970s north London at face value. The filmmaker Temple doesn’t intervene, no one does (we just get the audience’s gleeful reaction), his camera just observes. How authentic it all is is anyone’s guess. What’s certain is that Suggs comes out of this very well indeed, proclaiming at the end that, after all, all we need is love before performing a lovely rendition of “It Must Be Love”. Do devoted fans get a markedly richer sense of who Graham McPherson is after 90 minutes of jolly spiel. No, not really.

In fact, the list of hagiographies is pretty long, with Shane Meadows’ Made of Stone (2013) being one of the greatest offenders. His film is a rousing exploration of the Stone Roses’ successful 2012 reunion, after a 16-year split, and chronicles the Manchester act’s stirring and intimate comeback gig at Warrington Parr Hall. However, the film completely manages to skirt over the dramatic walkout of drummer Reni early in their tour in Amsterdam. There is no in-depth explanation or questioning of why he left so dramatically and how it affected the band. Meadows seems fixated on keeping everything positive and upbeat, which is disappointing and remiss for a documentarian. It affects the authenticity of the document, which simply becomes a fan’s eye look at a favourite band relentlessly singing the act’s praises and leaving out the icky bits.

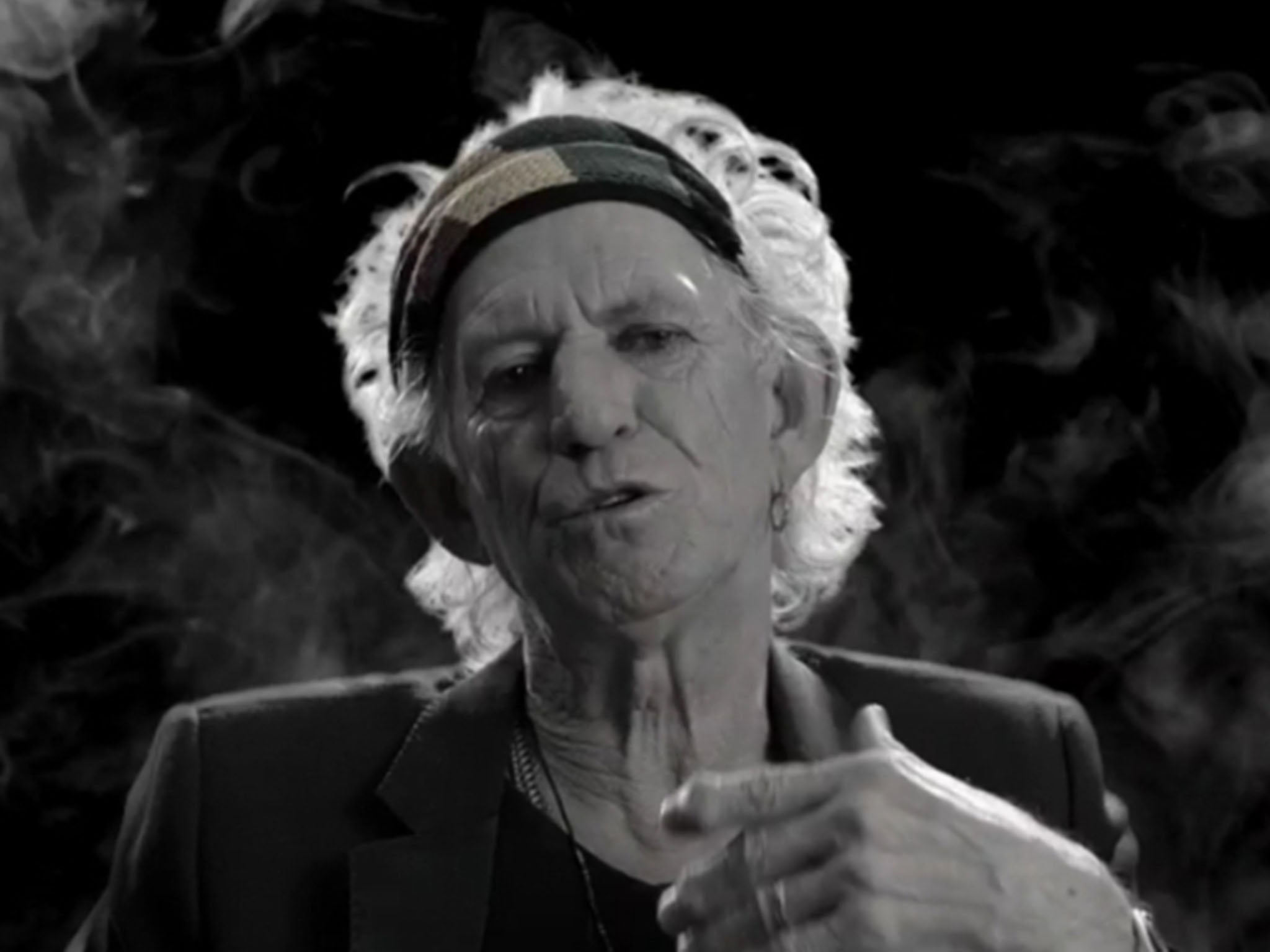

Quite often the films are approved and rubber-stamped by the artists themselves, which felt like the case with Julien Temple’s 2016 documentary, The Origin of the Species, about Rolling Stone Keith Richards. The gushing film came across as an overly cosy and frankly dishonest portrait; hero worshipping Richards to an unhealthy degree and not sufficiently challenging his bolder claims. A stark contrast to Robert Frank’s considerably more controversial and challenging Cocksucker Blues, about the Rolling Stones on tour in 1972, depicting debauchery and multiple drug use. The film has been largely suppressed by the band.

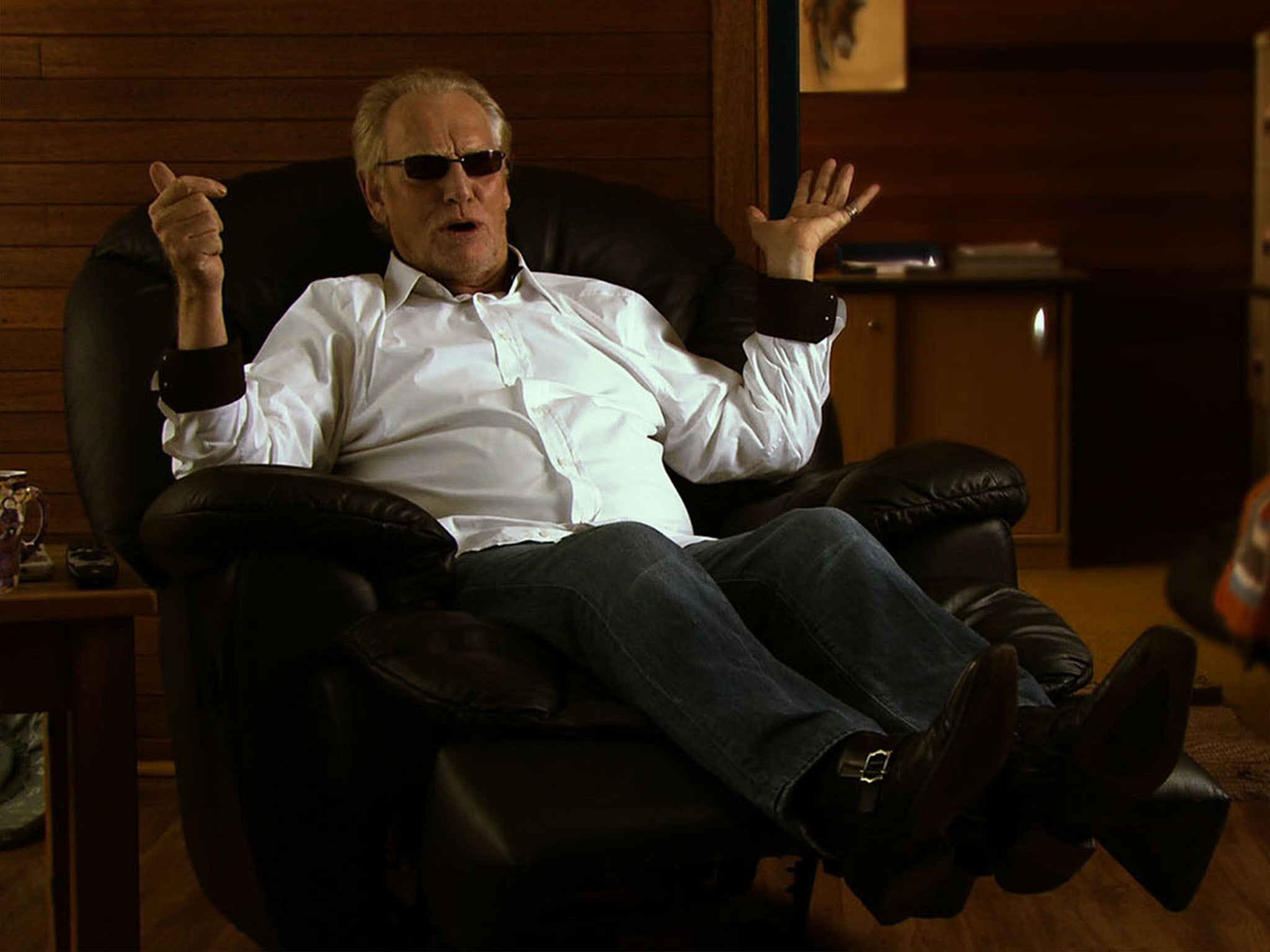

There are a few exceptions to the rule, most notably Jay Bulger’s excellent 2012 film on Ginger Baker, Beware of Mr Baker, the mercurial, misanthropic former drummer for Cream. It’s genuinely a warts and all experience in which Baker, at one point, bashes the director on the nose with a metal cane and calls him a “dickhead”. It’s not pretty. Also, Tom Berninger’s Mistaken for Strangers (2013), which explores his relationship with his brother, The National’s frontman Matt Berninger. It’s a funny, truthful and poignant film, and all the better for it.

But, on the whole, music documentaries play it safe, from the recent Supersonic, about the rise of Oasis, to the sweet Anvil: The Story of Anvil, about the American heavy metal band, and Alan G Parker’s Hello Quo (2012), which takes a relatively gentle look at Status Quo’s career. They’re all perfectly serviceable and persuasive movies, but they – in the main – sidestep criticism and serious analysis. You can’t help but feel that musicians, especially at the higher end, are somewhat getting away with it. For now.

‘Eric Clapton – Life in 12 Bars’ is released on 12 January and Julien Temple’s ‘Suggs: My Life Story’ is released on 17 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments