Eels: ‘Both my songs of the year are by people in their 70s!’

The mercurial LA songsters are back with their sweetest-natured album ever. Laura Barton talks to the band's founder about being reclusive, old-school songwriting and why online shows are sterile and depressing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The imagination of Mark Oliver Everett has long been a vivid source of material for songs. As “E”, the founder of the band Eels, his lyrics have encompassed God, werewolves, novocaine and peach blossom. He has sung of field mice, head lice, spiders and Susan’s house, and when the band prepared to launch their latest album, Earth to Dora, Everett chose to promote it by posting an imaginary conversation between himself and his great musical hero John Lennon.

But the gift of Everett’s songwriting is its combination of that rich imaginary world with the starkness of fact. Across 13 albums, Eels have tackled spectacularly brutal and intensely personal subjects. Their second album, Electro-Shock Blues, set out their stall early, addressing Everett’s experience of becoming the only living member of his family, following the early death of his father, the suicide of his sister, and his mother’s terminal lung cancer. In the 22 years since, his life has not been uneventful: there have been two marriages, two divorces, a son, all of them documented in song.

Today he is at home in Los Feliz, an eastern neighbourhood in Los Angeles, where Eels first formed in the 1990s, and about which Everett once wrote a song, “Mansions of Los Feliz”, told from the perspective of a local hermit.

Everett says that he too lives “a pretty reclusive lifestyle” these days, but that it has prepared him rather well for the enforced seclusion of a pandemic. He works from home. He looks after his three-year-old son. He spends a lot of time on his back porch, watching the birds. He pauses for a moment and contemplates his routine. “Be nice to get out a little more,” he concedes.

Eels should be out on the road now. “I can’t believe that was only a year ago we were on tour, it seems like 20 years ago,” he says. “We’re just dying to get back out there.” Online shows just don’t hold the same appeal for Everett. “It’s a tough thing, I’ve not been a big fan of it so far because it’s so sterile and depressing and just reminds me that we can’t all be in the same room,” he says. “Most singers nowadays use in-ear monitors and I can’t use them because I just feel too isolated, I need to hear the people in the room and feel that I’m part of the room. So the livestream thing is just an even more extreme version of in-ear monitors.”

Earth to Dora was written largely before the world went into freefall. “And maybe it’s a good thing that I wrote most of it before everything really got so crazy and the upheaval this year?” he wonders. “Because I don’t know that I have the voice for the political times!” Instead the album is perhaps the sweetest-natured record in the Eels canon, a result of Everett’s interest in “old school singer-songwriter writing, more traditional instrumentation and tunes and melodies”. His hope is that it might remind listeners of life before 2020, and “things we are dreaming about getting back”.

For all its soothing properties, Earth to Dora also holds some more abrasive moments. “Are You F***ing Your Ex?” for instance, is a blunt, accusatory and profoundly catchy number. “I always like to try to reflect all the different sides of a situation and it’s a little tricky getting something as jarring as “Are You F***ing Your Ex?” into happier or prettier songs,” Everett says, his voice measured and low. “But the arc of the songs on the album goes through a bit of a dark period in the middle. I think it would get a bit boring if it was all happy and lovey-dovey the whole time! You’ve got to get a little drama in there.”

I wonder if Everett’s ideas of album and song structure have been influenced by his experience of writing a memoir (Things the Grandchildren Should Know was published in 2008), and by making a documentary (Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives looked at Everett’s relationship with his father, Hugh Everett, the physicist who first proposed the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics).

“I guess in a way it’s similar to writing a book about your life,” he says. “I was very conscious [with this album] that I wanted it to be a chronological story. The songs on this album weren’t written to reflect a certain relationship, and they’re not really all about a certain relationship, but I did lay them out in a sequence where some listeners, if they want to, can think of it that way.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

There is a particularly arresting track on the album named “Who You Say You Are”, which takes on new texture in light of Everett’s comment. It captures the very particular woe of the songwriter, writing a song about a certain someone only later to no longer feel so certain about them. “It’s kind of a song about writing a song in a way,” he agrees. “It’s trying to tell myself to be a little more cautious sometimes. There’s a line in there that says ‘Charming accents mask ugly things…’” I hear him smile down the line. “So don’t you try coming over here with your charming English accent!” he says. “I’m not going to fall for it any more!

“But not all my songs are autobiographical,” he continues. “Probably about half of them are, and the rest of them are based on something that’s happened, a friend of mine’s story, and some of them are just fiction.” The track “Anything for Boo” is certainly a fantasy of sorts, with its familiar name-checks of Taylor Swift and Tropicalia singer Gal Costa.

“It feels like as an established artist at this point in my career I need to help the little acts that need exposure that people don’t know about. Like Taylor Swift,” Everett deadpans. I tell him Taylor will surely appreciate this act of generosity. “Yeah,” he says slowly. “I’m really good at picking up these obscure artists and I think it’s really going to help them.” Which Eels song would he most like to hear Taylor Swift cover? He considers this for a moment. “I think Taylor would do a great version of ‘Are You F***ing Your Ex?’ actually,” he laughs. “That makes a good raw turn for her to take!”

As the nods to Costa and Swift attest, Everett’s musical tastes are broad. He relishes the new finds he comes across on YouTube, and ties Bob Dylan’s “Murder Most Foul” and Bettye LaVette’s cover of The Beatles’ “Blackbird” as his songs of the year. “And they’re by people in their 70s,” he notes. “So that gives me hope that you can still be artistically vibrant at such an age.”

Through his son, Archie, he finds a new perspective on music, too. “There was a night recently where we were reading a Peppa Pig book,” he says. “Daddy pig takes the kid to his office to show them his work and Archie said, ‘Would you show me your work?’ And so the next morning I took him up into the attic where the studio is and tried to explain in three-year-old terms what we do up there. And I took him down into the performance part, which is also half his playroom, and showed him how I plug in a guitar and how I sing in a microphone. And he said, ‘Now I’m going to show you my work!’ And he grabbed his three favourite stuffed animals, and his toy piano, and his toy guitar, and they all performed ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ for me. So that was pretty great.”

In his own childhood, Everett’s music tastes were out of step with his peers. “At school I was the weirdo for liking The Beatles,” he recalls. “They were old men, and everybody was into whatever the Top 40 hits were at the time.” Still, he found even greater musical sustenance in John Lennon’s debut solo album, Plastic Ono Band. “It was weird for a 10-year-old to be so into so stark a record,” he admits. “But it’s also such a pretty, beautiful record.”

As Everett observes to Lennon in his fictional interview, it was Plastic Ono Band that “pretty much set me on my path”. That path, clearly, was not just a career in music, but in marrying music to starkness and to beauty.

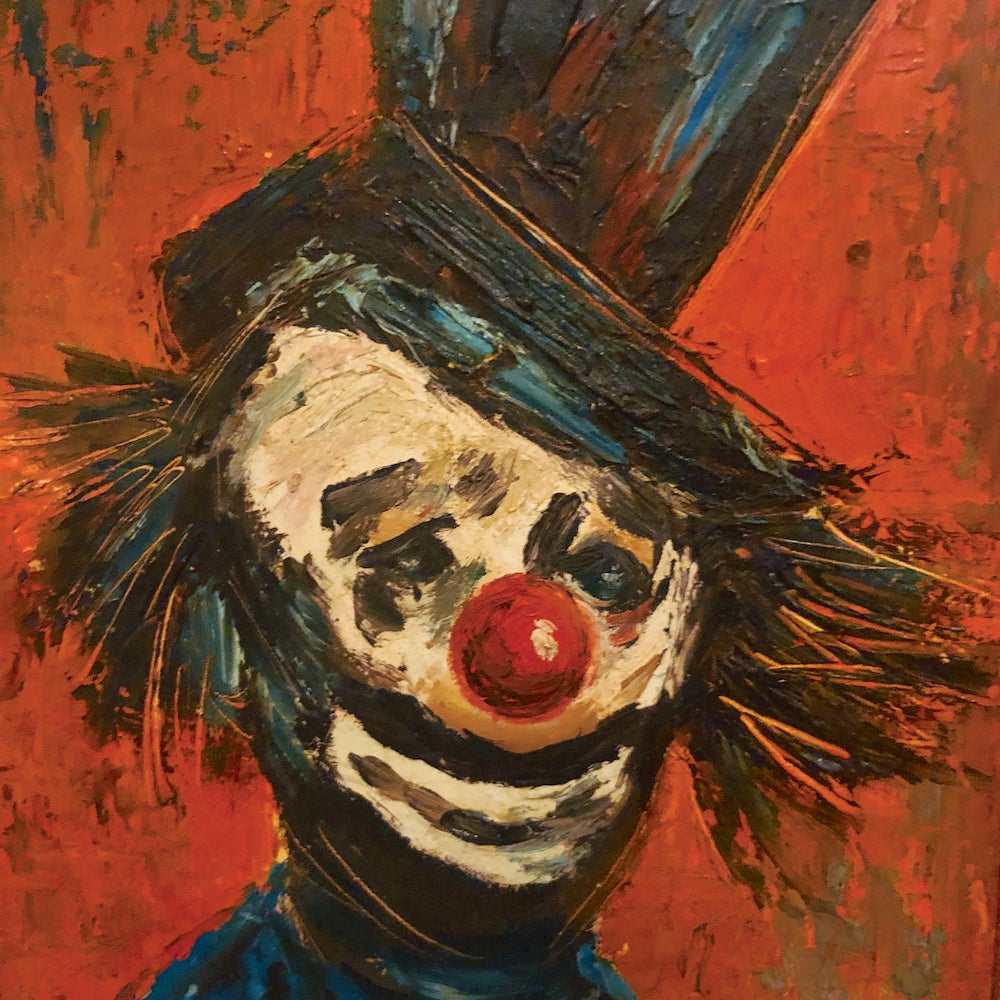

Thirteen albums in, the path remains much the same. Everett points to Earth to Dora’s sleeve artwork – a painting of a clown from a neighbourhood thrift store that had been hanging on his bathroom wall for the best part of 10 years. “And while we were making these songs, I was in the bathroom taking a piss and looking at it,” he recalls, “and it suddenly struck me: that’s the album cover!” As he speaks, I look at the artwork: a sad-eyed and slightly skew-whiff clown, smiling broadly beneath his dishevelment. “The clown looks like he’s been through some tough times but he’s managing almost fine,” Everett says. “He knew he was going to be OK.”

The new Eels album 'Earth To Dora' is released on Friday 30 October via E Works/[PIAS]

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments