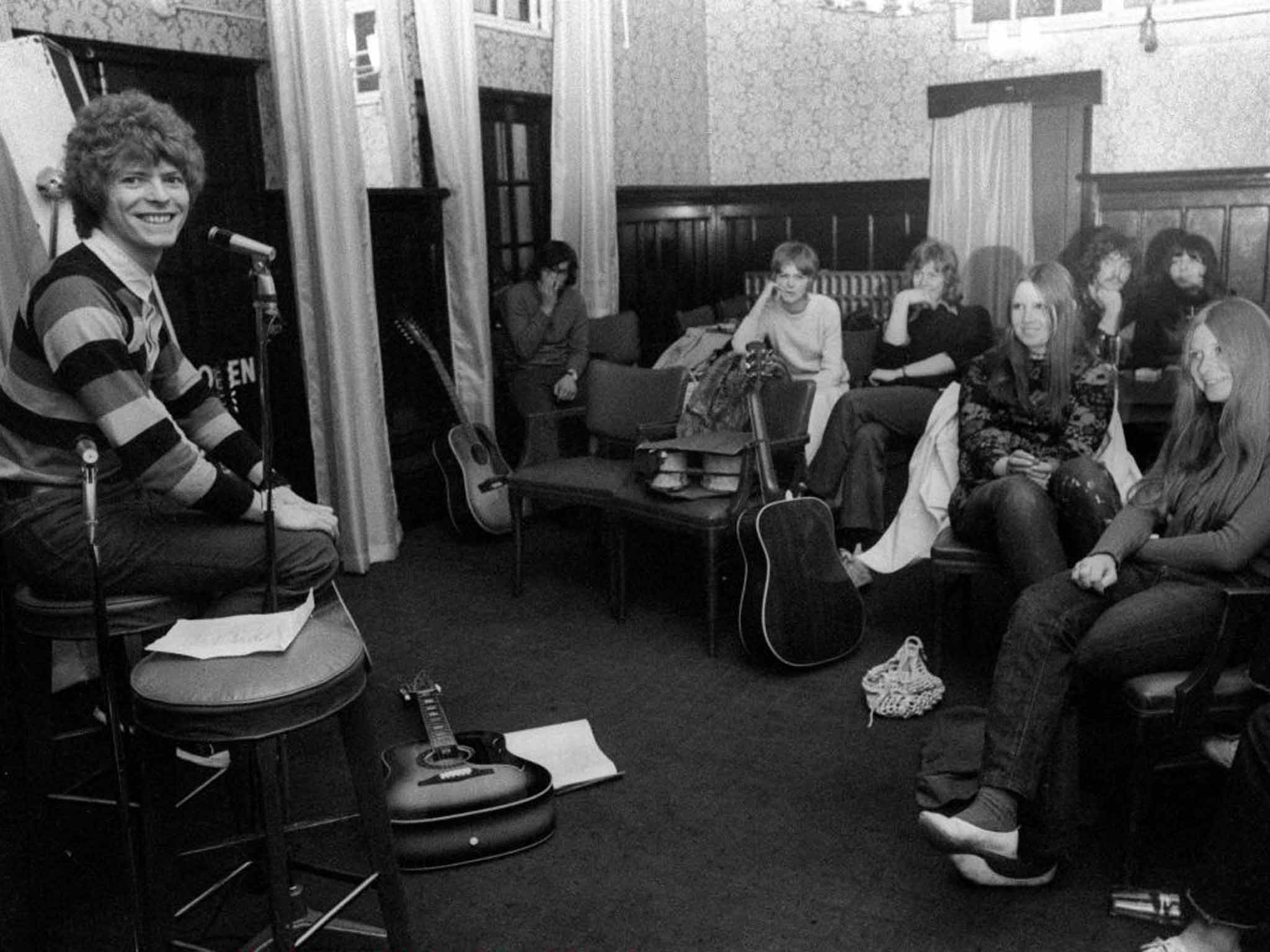

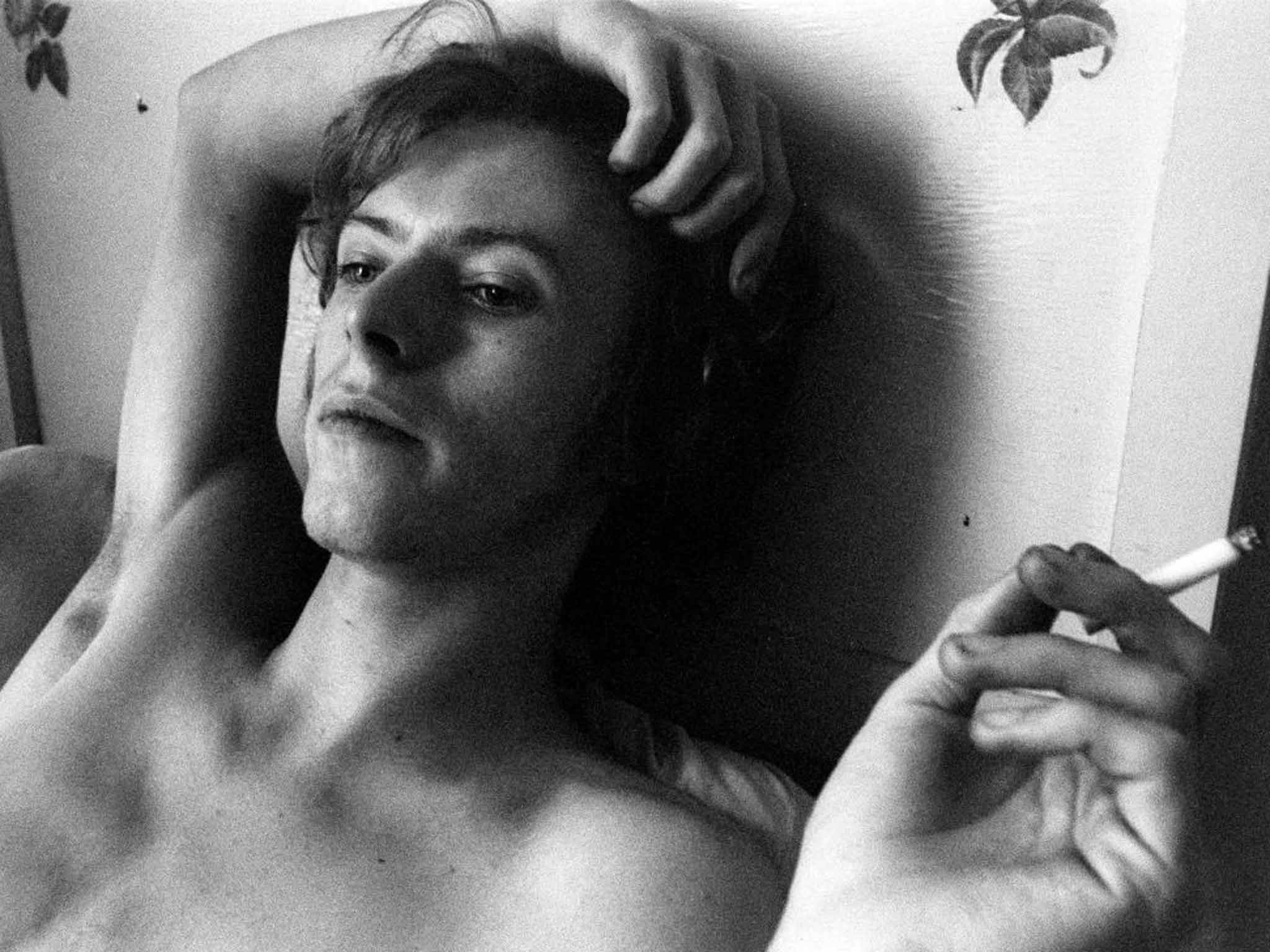

David Bowie, the lodger from Mars: Mary Finnigan on life with the music star in the 1960s

Hours after meeting a penniless young man from Bromley, Mary Finnigan invited him to stay. In this extract from her new memoir, she conjures a heady time in the late 1960s when a terrestrial phenomenon on the brink of stardom moved into her home and, briefly, her bed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On the return leg of a long zone-out I become aware of a voice and a guitar making music that is entirely new to me. It is confident, personal and melodious. This, I think, is not your average wannabe rock star. This is something special.

“Who's playing?” I call, as the song ends. A pale, thin face, framed with a halo of curly blonde hair, appears in the open window.

“Hello,” he says, politely. “I'm David. Who are you?”

We both smile real smiles, not pretend ones.

“I'm Mary. Would you like a cup of tea and some tincture of cannabis?”

Intrigued, because he'd never heard of tincture, David Bowie, plus 12-string Gibson, comes downstairs. We have tea, tincture and biscuits, then cake and a graze from the fridge, and what starts as a brief encounter ends up stretching into evening and night.

As the tincture works its magic, we talk, with conversation punctuated by more songs, each one an original composition, the result of David's inspiration and hard work. I learn that he and my friend Barry were schoolfriends. David tells me he's been in the music business for several years and has already released an album, which was not promoted and did not sell.

He has split up with his girlfriend and is living awkwardly with his parents in nearby Bromley. He tells me he sees himself as a radical singer-songwriter but his manager, whose name I'm told is Ken Pitt, wants to turn him into a mainstream pop idol. He's not happy with his manager and he's broke.

“Can you afford a fiver a week? I have a spare room – you can be my lodger if you like.”

This impulse flashes into being from who knows where – certainly not my brain, because I only met this guy a few hours ago and here I am inviting him to move in.

David says “Yes, please.” I think I know in my heart that the fiver a week is theoretical and that, for him, an easy alternative to living at home is an opportunity not to be missed.

He wanders back to Barry's in the small hours and I go to bed wondering what will happen next.

My insecurity turns out to be groundless, because a couple of days later he arrives on the doorstep ready to move in. Today there is just David, a suitcase, the Gibson and a small oblong box. He parks himself on a stool in the kitchen while I make lunch.

“Can I play you a new song?” he asks.

“Yes please.”

This is the first time I hear “Space Oddity”, and it's my first encounter with a strange instrument called a stylophone, a battery-powered electronic device with a keyboard played with a stylus. It sounds like a cross between an organ and a jet engine – and absolutely right for a melancholy song about a space mission gone wrong.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

David explains that “Space Oddity” was written for two voices – his and his friend John Hutchinson's. He tells me that Hutch is a cool guitar player and that he was a member of a mime and music threesome called Feathers. The third member was David's ex-girlfriend, Hermione Farthingale. Feathers disbanded after a short lifespan when David and Hermione split up. David tells me of his plan to perform as a duo with Hutch, but he's not sure it will happen because Hutch's wife, Denise, has other ideas.

To his later chagrin, Hutch took his family back to his hometown of Scarborough, leaving David with a solo career and a song that was written for two people. With his usual ingenuity, David got round this problem in live performance by singing one part and playing the other on a tape recorder.

My kids come home from school and are instantly fascinated by the stylophone. David appears to be completely at ease with Caroline and Richard, explaining how the instrument works and letting them have a go. He plays “Space Oddity” again and we are unanimous that it's a fabulous song.

“It should go to number one,” says Caroline. “I hope it does because I'll be able to impress my schoolfriends.”

The refrain about a spaceman floating in a tin can triggers Richard's imagination. He disappears off to the kids' room, to return a while later with a drawing of a spaceman in his capsule, surrounded by the moon, planet earth and various other extra-terrestrial phenomena. David discusses it with Richard, suggesting other things that could be included.

He is an immediate hit with the kids and it becomes clear to all of us that, with David as our lodger, our humdrum suburban life is about to go through a gear change.

David has no money and no gigs, so he spends most of his time in the flat but is by no means idle. I have to admit to myself that when it comes to single-focused dedication, David the musician outranks Mary the journalist by a wide margin.

There is music in our lives throughout the day and frequently far into the night. He composes one new song after another, scribbling lyrics in a notebook and figuring out tunes on the Gibson. We are witnesses to a creative process that goes through stops and starts, hiccups and variations. Then when he feels OK about a song, he asks politely, “What do you think of this?”

On warm afternoons he sits on the swing in the garden, working on words and music, usually with one or both of the children messing about around him. “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud” comes into being during one of those sessions, inspired by Richard's games. David starts on a song called “The Circling Sponge”, especially for Richard, but I doubt it will reach completion.

Sometime after his arrival, David expresses concern that Richard is bonding with him. “This could be a problem,” he says. I don't see it as a problem, but I should have been more alert. He issues an oblique warning – and I ignore it.

Having David living with us is a new, invigorating experience. I am happy, the kids are happy – none of us at this stage see his presence as transitory.

From the start, we do not observe landlady-lodger conventions. I am happy with this arrangement – we share the tincture and Lucy's deliveries of high-quality hashish. We share the space, cook and eat together. And a few days after he moves in, David and I sleep together.

The seduction is a work of art and takes me totally by surprise, when I come home one Saturday evening after a shift at The Sunday Times (edited in those days by my friend and journalistic mentor, Harry Evans).

Usually I return to a messy kitchen and a sink full of dishes, showing evidence of baked beans, fried egg and tomato ketchup. But on this occasion, interesting cooking smells greet my arrival, the kitchen is clean and tidy, with the table laid for two plus flowers, candles and incense. The kids are fed, washed and tucked up in bed.

After a spliff and a nice dinner, David creates a nest of cushions on the floor of his room. He settles me into it and places speakers close to my ears on each side. Then he plays me a selection of his current favourite musical influences.

Some are obscure, others well-known – Jacques Brel, for example, and mind-blowing stereo phasing from Jimi Hendrix.

Snuggled up, stoned and together, inevitably one move leads to another.

David must be confident that he has become an accepted member of the Finnigan household, because early one morning the full impact of his arrival manifests in the form of a friend of his turning up on the doorstep, ready to unload the contents of a dilapidated van.

The friend is in a hurry and I am still half-asleep. He squeezes past me carrying two large, battered stage speakers. Two amplifiers land in our narrow hallway, followed by a tape deck, an electric guitar, several mike stands and an assortment of cardboard boxes, loosely packed with leads, plug boards and other assorted musical paraphernalia.

Apart from identifying himself and muttering a surly “bye, then”, van man says nothing and leaves as quickly as he arrived.

David is still asleep in my bed.

Caroline emerges from the children's room at the far end of the corridor, late for school and in urgent need of the loo, but her route to the bathroom is now blocked by a vanload of David's professional equipment. Watching carefully where I put my feet, I navigate a path to the point where I can lean forward to lift my daughter and then put her down within reach of the bathroom door.

“This won't work,” she complains, and I agree. Apart from other considerations, Caroline is a sturdy 11-year-old, so hefting her off her feet is not something I want to do on a routine basis. Richard is younger and lighter but also late for school, so that morning there's a repeat performance with him.

David usually sleeps until around midday, but after the kids leave for school it's coffee and wake-up time and, when he's more or less fully conscious, flat reorganisation time.

Initially, most of the gear goes into David's room, but by the time we have packed it all in, it is not easy to move from the door to the bed.

“This isn't going to work,” I say – and he agrees.

We take a break, have breakfast and start negotiating. David warned me that he needed his kit. I had agreed to have it in the flat, but until that day I had no concept of how many cumbersome items were involved and how much space they would occupy.

After examining various options I reluctantly accept that the speakers can go in the former dining room, now a chill-out room. They are the bulkiest items and their new location represents a radical re-alignment of my domestic priorities.

The days when I hosted elegant dinner parties were already long gone, but with the advent of David Bowie in our family life, the room where I usually entertain friends is in the process of being transformed into a music studio.

It turns out that the speakers don't stay in their designated location all the time. Sometimes they migrate to the sitting room and sometimes out into the garden, while the amplifiers stay behind. This means that the hallway in between is booby-trapped with wiring. This is not dangerous, but is the cause of occasional grumbles from the kids.

How, I hear you ask, did David manage to pull off this takeover? And why was I so docile and compliant?

The answer to question number one is that, even in the early days of our friendship, I was spellbound by his charisma, his charm and his talent. I had been a man-free zone for many months and now there was this handsome, sexy, interesting male creature occupying centre stage in my life – out of the blue and at high velocity.

The answer to the second question is more complex. I was brought up by a mother who indoctrinated me with puritanical values, left over from the Victorian era. Shortly before she died in 1989, I discovered that my mother was in fact a liar and a hypocrite; but 30 years earlier, my legacy from her was extreme naïveté coupled with low self-worth. I had only recently discovered feminism, and had not yet managed to integrate the principles of gender equality.

At this point in time David is not pushy or rude – he is, in fact, quite gentle, but he is also a strong character who is used to getting his own way. I am happy to oblige, and not just because of my emotional immaturity.

Being in tandem with David generates excitement, fun, pleasure – and new horizons. There is always an undertone of ambivalence around David's status. Theoretically, he is my lodger. But he is also my lover who I naïvely assume to be monogamous. He is seven years younger than me, very horny and sexually sophisticated.

At least once a week he takes the train to London to patrol the folk clubs, looking for work and inspiration. David describes himself as a folkie, but to my ears his songs cannot be pigeonholed.

Living from hand to mouth, he also does casual shifts from time to time at Legastat, a copying office on Carey Street in central London. During these absences he claims he stays with “my friend Calvin”.

Eventually David tells me more about his friend, Calvin Mark Lee. He is a Chinese-American from California, an A&R man with Mercury Records, and has spotted David's talent. Calvin is bisexual and, I discover later, involved with both David and a very pretty young American girl called Mary Angela Barnett [later to become David's first wife].

David also tells me about his love and respect for the mime artist Lindsay Kemp. Lindsay was David's mime and stagecraft guru for a while and was also his lover – but again I did not find out about the physical aspect until much later. Lindsay's influence penetrated everything that David did as a performer for many years.

Lindsay occupies the high-art end of the entertainment spectrum in a lineage that includes the legendary mime maestros Jean-Louis Barrault and Marcel Marceau.

David and I spend lots of time together in cosy fireside conversations. In one of them, I'm surprised when he tells me he's never done LSD. He hints that he finds the prospect of losing control during the psychedelic experience terrifying.

He mentions his half-brother Terry's mental illness. “He's schizophrenic and it probably runs in the family,” he says.

David's interest in Tibetan Buddhism is another fireside topic. It's familiar territory for me and I am very interested. I'd dipped into Zen meditation, and read The Tibetan Book of the Dead after being impressed by the version of it co-authored by Timothy Leary, The Psychedelic Experience.

The non-theistic, contemplative basis of Buddhism was calling me before I met David. I saw it as a logical extension from LSD, but in David's case he bypassed the chemical catalyst.

David tells me about meeting the Tibetan lama Chime Rinpoche when, on an impulse, he ducked into the Buddhist Society library to escape a rainstorm.

Chime became David's meditation teacher, mentor and friend. One of only four Tibetan lamas in the UK in 1969, he was a monk in maroon robes, although in common with many lamas who migrated to the West, he disrobed soon afterwards when the temptations of the flesh became irresistible.

David tells me that he used to be serious about Buddhist practice. I have already realised that casual interest is alien to his nature – whatever David does, he does full-on, with concentration and single focus.

He says that for a while music was on the back burner, when he went to Samye Ling in Dumfriesshire, the first Tibetan dharma centre in the developed world.

He considered being ordained as a monk, he says, but the music would not go away. “On the cushion, it echoed through my meditation,” he says. “It was with me while out walking in the hills and, sooner rather than too late, I realised I was not being true to myself.”

'Psychedelic Suburbia: David Bowie and the Beckenham Arts Lab' by Mary Finnigan (£14.95, Jorvik Press) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments