Chrissie Hynde: ‘The music industry is yet to have its #MeToo moment’

The Pretenders’ singer looks back at the problem with the groupie era, asks why more women didn’t form bands, and talks about her new album with Laura Barton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

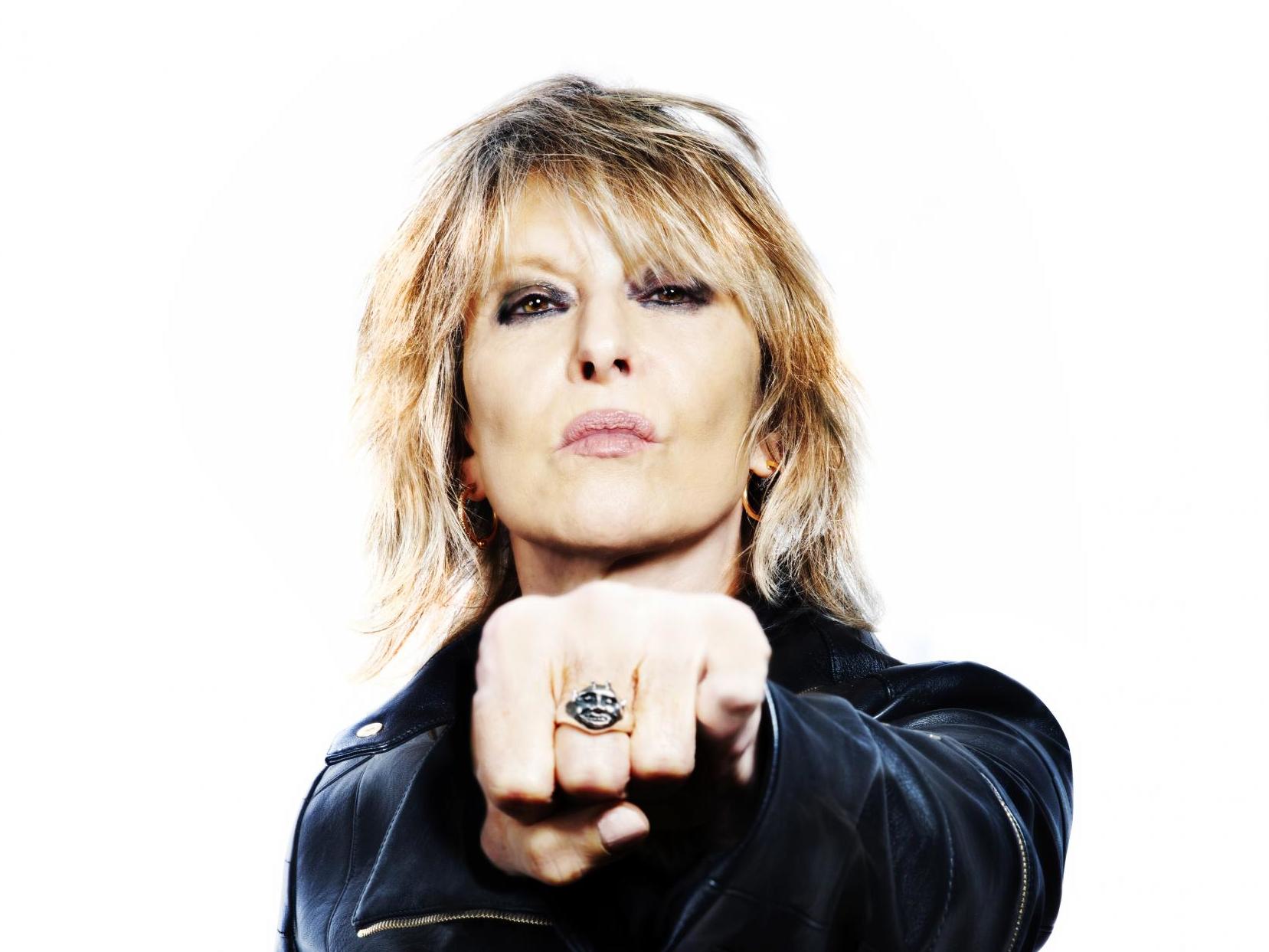

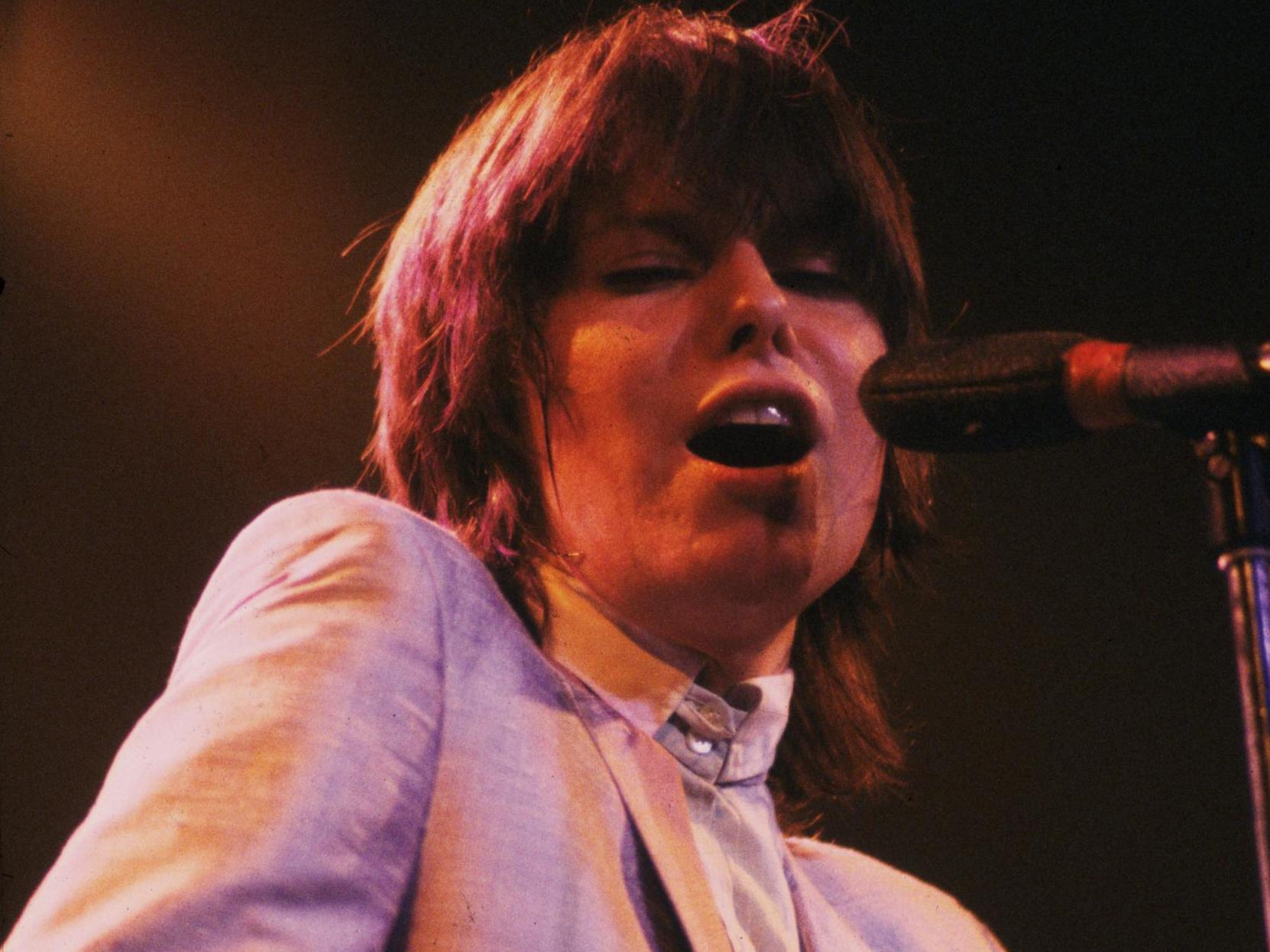

Your support makes all the difference.There is a question that nags away at Chrissie Hynde, now some four decades into her music career: “Why didn’t more women get into bands?” She frowns and scrunches her eyes. Hynde wears her hair lighter these days, but her eyes are still as heavily kohled and fringe-buried as they were in The Pretenders’ early days. “Some will say ‘Because we weren’t encouraged!’” she continues. “But that was the whole point of being in a band, that you weren’t encouraged, so you were like ‘F*** it, I’m doing it!’”

Lately she listens to women in other industries talk about the struggle of their professions, the compromises made, the sexual favours they were asked to perform. “And I’m sitting there thinking, ‘Why didn’t you just get a guitar? Why didn’t you just get in a band?’ A lot more girls could’ve gotten in bands if they’d wanted to.” She repeats the lines slowly: “If they’d wanted to. But they didn’t want to. There is no other explanation. They just didn’t want to. They probably were frankly just too busy looking after their boyfriend. That’s the truth! So I’m not allowed to say anything like that now, but I don’t give a s***! I’m the living proof!”

In recent years, Hynde’s opinions have at times provoked controversy. There was the time she was arrested for smearing “blood” across the windows of a branch of KFC, and more recently her comments on sexual assault: “If you don’t want to entice a rapist, don’t wear high heels so you can’t run from him,” she told The Times four years ago. “If you’re wearing something that says, ‘Come and f*** me’, you’d better be good on your feet.” Hynde’s memoir, Reckless, had detailed her own sexual assault by the member of a motorcycle gang when she was a teenager, though she was adamant that she had played a part in encouraging his behaviour. “You can’t paint yourself into a corner and then say whose brush is this?” she said. “You have to take responsibility.”

Today she is charmingly and equally forthright, insistent that she has never been the subject of any kind of gender discrimination during the four decades of her career. After delivering a potted history of the music industry of the past 80 years, she describes the point at which “MTV came along and some women realised that if they did some kind of soft porn-type videos they would get on TV and they would sell – because sex sells. And I think the standards plummeted very quickly. The interesting music then went back underground for a bit.”

She was never encouraged or pressured into making such videos herself, and insists she had the right to refuse. “I don’t think there is any pressure,” she says. “I think people wanna do it or they don’t do it. People say they’re pressured, but really the buck stops with the artist. If you don’t want to do it say, ‘I’m not doin’ it.’ That’s why you’re in this position: because you’re doing your own thing, and the executives aren’t doing it.”

“Have you watched the Harvey Weinstein documentary?” Hynde asks idly. “I had no intention of watching it but it popped up and I was interested.” It attracted Hynde for various reasons, not least the fact that, with 18 months in age between the rock star and the film producer, their lives and careers have run somewhat in tandem. Social circles overlap. Degrees of separation are few.

She narrows her eyes now as she talks about Weinstein and the #MeToo era. The most interesting thing about the documentary, she says, was not that so many people turned a blind eye to the behaviour of Weinstein and co, but rather “the way things evolved”.

She tells how recently she read an interview with Anjelica Huston in which the actor was talking about Roman Polanski. “She said a great thing about how when she grew up we were living in a sort of Playboy culture, where you had these women of their own volition dressing like rabbits, in their underwear, and that was cool at the time. And all the older guys were used to hitting on young girls because the girls were offering themselves up on a plate. Now I’ve seen that unfold over three more decades and you can see the way it went.”

She believes the music industry is yet to have its #MeToo moment “because the girls were groupies and they really were offering themselves up”. And while The Pretenders may have had a few “hangers-on”, there were never any male groupies. “A male groupie is a fan,” she explains firmly. “It’s not the same. A male groupie is not someone who’s going to offer you a blow job.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

There are very few female rock musicians who have enjoyed the success and longevity of Hynde, and though she is feted as a trailblazer and feminist role model, she refuses to wholly play the part. “I was never hit on, and no one ever suggested I do anything,” she says. “Sexism and discrimination never came into it with my band. It was all about having some songs and playing them. I’ve never had a problem! It’s fantastic. But now I’m apologetic. Because people, especially women, are always like, ‘Didn’t you have to work harder?’ And I’m like ‘No’.”

We are in her publicist’s office. Hynde is looking out over the streets of Marylebone, over the station awning to the building opposite, once one of the great Victorian railway hotels. She remembers when it was still the Regent, and when it was empty, and when the stretch of paving in front of it appeared in the Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night. “That’s the thing now,” she says. “Wherever I go I remember the buildings as they were. And no one else knows it because I’m older than everyone now.”

Hynde turned 68 two days before we meet, an occasion she celebrated by releasing her 15th album, Valve Bone Woe – an unexpected jazz dub covers collection in which she turns her smudgy, languorous voice to everything from Hoagy Carmichael’s “I Get Along Very Well Without You (Except Sometimes)” to Nick Drake’s “River Man”. It’s no schmaltzy retrospective, rather the fruits of a long-running project with producer Marius de Vries, an experiment in melody, and a nod to the Charles Mingus records she heard drifting from her brother’s record player as a teen.

This afternoon she sits at the office conference table in a hooded sweatshirt, eating a black jack she swiftly regrets. She talks lightly and somewhat dutifully about the new record, but her conversational topics are many and various, ranging across everything from the early days of The Pretenders, growing up in Akron, Ohio, London’s punk clubs of the Seventies, the writing of Niall Ferguson, her late-flowering love for karaoke, and her furious passion for Mark Morrison’s 1996 single “Return of the Mack”: “I lived for that,” she says. At one point she pauses and enjoys a breath of contemplation. “Anyway,” she declares, “I’m an expert on everything.”

When she moved to London from the US in 1973 it was not with any great plan. An art school graduate who could play the guitar, “all I knew was what I didn’t want to do, and I didn’t want to be a waitress,” she remembers. Amid London’s burgeoning punk scene, she knew that to be a girl in a band would be a novelty, “And I didn’t want that either.” And yet she was desperate to play. Her “love of wanting to be in a band” had to override many things: the shyness she felt playing guitar around her male counterparts, “having no money, working illegally, coming here and not knowing anyone,” she lists. “It’s not even about self-belief, it’s not about confidence, it’s just about loving music.”

She has two daughters, Natalie, from a relationship with Ray Davies of The Kinks, and Yasmin, from her marriage to Jim Kerr of Simple Minds. Motherhood placed an intermission in her flourishing career. “Well, like any other woman I just couldn’t do it for a while,” she says. “I didn’t tour for about eight years. I obviously was very distracted a lot of the time. And writing rock songs... the whole mindset changes.” Still, she believes that motherhood has given her a creative longevity “because you don’t burn yourself out, because you have to restrain yourself for a while and pull back”.

For the first time it’s not a break-up album. For the first time I’m writing about other stuff

Hynde describes herself as now coming into “a quiet time” in her life – by which she means that since her daughters left home a hush has descended over her life. “I live alone,” she explains. “I forget to put the radio on, or I can’t find a station I like, or they’re playing marching bands on Radio 3 and I’m like ‘I can’t listen to that!’ Then I just turn it off.” Sometimes she wonders what it might be like if someone else were there. “If they put on some Japanese flute music or some Chet Baker I’m sure I would luxuriate in it,” she supposes.

At 60 she gave up smoking, drinking and taking drugs. “Alcohol is the real demonic one,” she says. “It’s so insidious because it’s everywhere and it’s the gateway to more debauched drugs.” She got sober in pretty much the same way she gave up smoking – by reading Alan Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking and then “you bite the bullet for a week”. She had contemplated giving up for years. “You wake up and you’re disgusted, and you throw it all away, and you say never again, and then you repeat it. And then there’s the self-loathing. Now I’m not recovering, I’m fully recovered. I never think about it.” Instead she has cultivated other preoccupations – she paints most days and does yoga each morning, wherever she is, pushing back the furniture in hotels and dressing rooms to run through her routine. “I stand on my head,” she says, “and I’m good to go.”

A longstanding campaigner for animal rights, she supports a farm in Rutland where the fields are ploughed by oxen and the calves never separated from the cows. “I think every 10 years, animal rights, like feminism, takes on a different complexion according to the way the world is working,” she says. “You have to review it and update it.” Today she is frustrated by many animal rights’ groups attitudes towards the farming community. “Because of industrial farming [all] farmers have been vilified,” she explains, “and that’s wrong, because we need farmers.”

Still she seems today propelled by a kind of irresistible hope. “I think we’re in such a great moment now,” she beams. “I think it’s almost like a renaissance we’re going through, and no one else seems to notice it – I find it very peculiar, because there’s so many positive changes.” She discusses a few of them: electric cars, Extinction Rebellion, the widespread availability of vegan food, gay rights. There are minor frustrations, of course – Trump and Brexit among them, “But that’s just a passing thing!” she swats them away. “These are real things! It’s unbelievable the changes in my lifetime.”

Early next year she will head out on tour once again with The Pretenders. Sixty US cities with the band Journey (of “Don’t Stop Believin’” fame). She enjoys touring – the movement, the music, the hotels. She mourns only the fact that she will not be able to do her own laundry. “This sounds really frivolous,” she laughs, “but I have one of those Lazy Maids, they’re fantastic – every time I do all my laundry and I get it up there and it’s all perfectly flat, I think, ‘God I’ll miss you when I’m on tour.’”

The tour will promote a new Pretenders album, co-written with the band’s guitarist. “When I first started writing, I could only do it alone with a guitar,” she says. “I didn’t know how to collaborate.” She remembers the time she met Bob Dylan, and he told her, “Hey, we should write some tunes!” (Hynde, incidentally, does a mean Dylan impersonation). She balked. “I didn’t know how to write with someone. I blew it off man!” she pauses and a smile rumples across her face. “I mean it was probably just a come on line,” she says. “Bob comes on to everyone.”

She runs through some of the new album’s themes – from turf accountants to addiction. “They’re not relationship songs,” she says gladly. “I read all the time about break-up albums and all of mine have been break-up albums, but I just never told anyone! Now, for the first time it’s not a break-up album. For the first time I’m writing about other stuff.”

One of the new songs is about loneliness: “‘I’m glad I got rid of you but I didn’t think I’d be this lonely...’ – that sort of theme,” she explains. Is she lonely? She considers the idea for a moment. “Living alone is hard work,” she says. “You have to be diligent at all times. Because there is no conversation. But it frees up all this other time to explore other things. That’s why I feel like I’m 15 now, because I live exactly like I did when I was 15, but I’m not worried about what I’m going to do with my life. All the hard stuff is behind me. All I have to worry about now is death.” Does she worry about that? “No!” she laughs. “I’m ready!”

She is distracted suddenly by something outside the window. “Sorry, look at those crows!” she says. “Look at that huge one on the awning there! And there’s the other one over there, I see, they’ve probably got something going on between them.” She watches the birds in rapt silence for a couple of moments. “Sorry,” she says, thoughts returning to the room and the conversation. “Loneliness is a really interesting subject.” She lists the pleasures of being alone in a city, the day spread out precisely as you want it. “Just being able to do what you want and how great that is,” she smiles. “I am a loner, I realise that now.”

Valve Bone Woe is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments