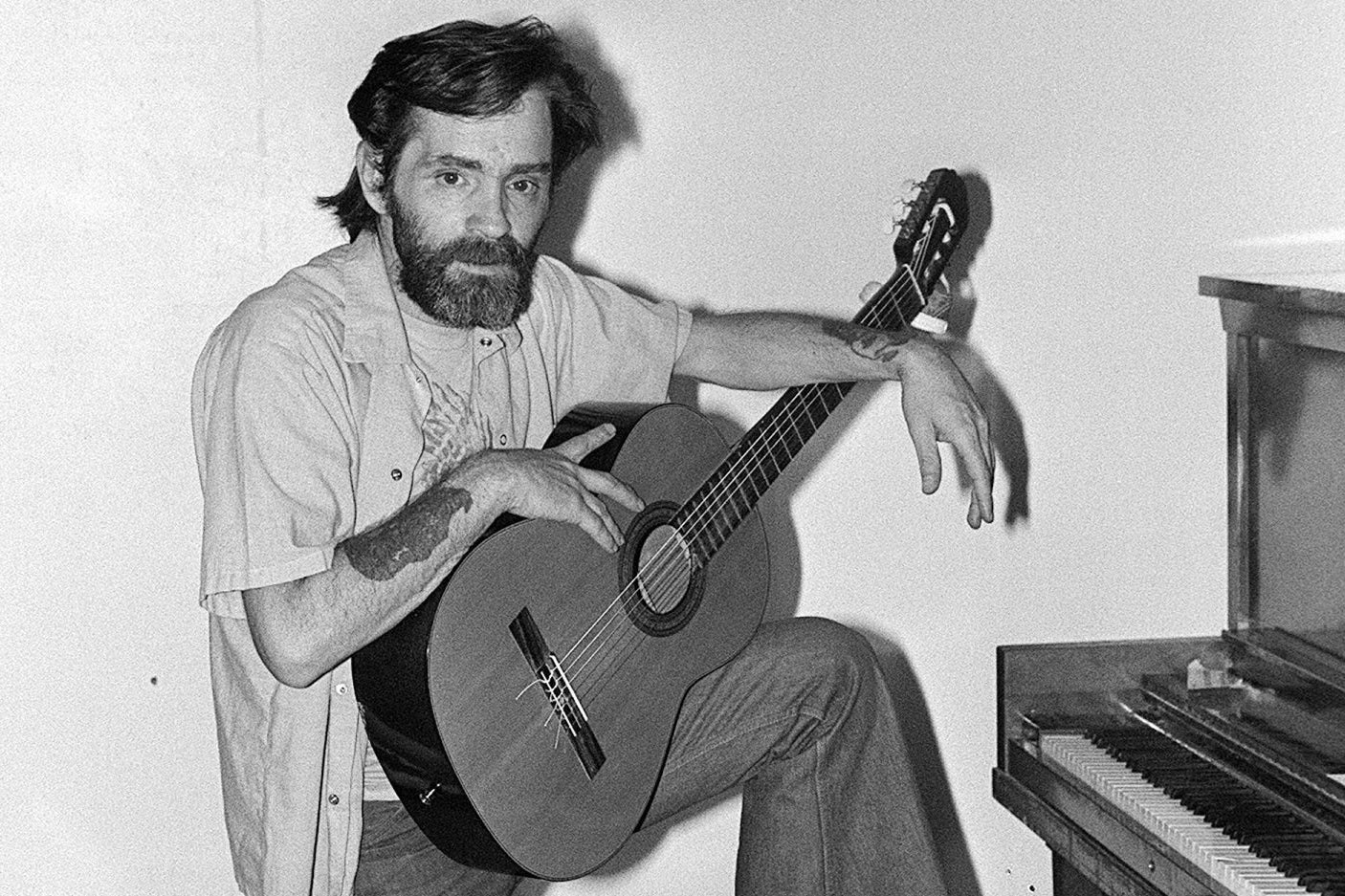

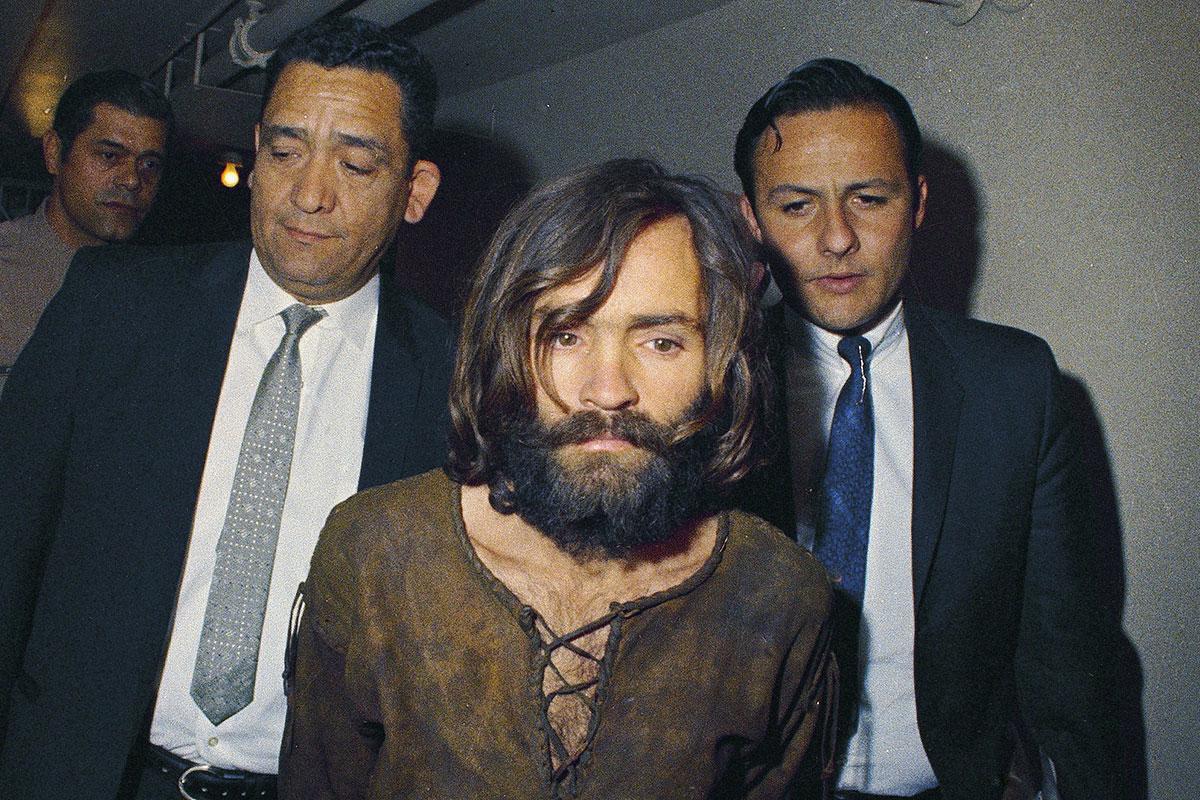

Charles Manson: mass murderer of unspeakable evil who left a dark and disturbing musical legacy

Mark Beaumont revisits the Manson murders of 1969 to assess the musical influence of the sadistic cult leader and would-be singer-songwriter who jammed with Neil Young, lived with a Beach Boy and made a lasting impression on Ringo Starr, Ozzy Osbourne and Nine Inch Nails

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 9 August 1969, the writing on the wall for the Sixties dream was smeared in blood. “PIG”, it read, daubed on the front door of 10050 Cielo Drive in Los Angeles, where pregnant film actress Sharon Tate and four others lay brutally slaughtered. The following night, over the bodies of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca on the walls of Waverly Drive, it read “RISE”, “DEATH TO PIGS” and, misspelt on the refrigerator, “HEALTER SKELTER”.

The hope of Charles Manson, cult leader of The Family who had planned and ordered the string of murders launched by his followers 55 years ago this week, was that these deaths would be blamed on African Americans, instigating an apocalyptic race war that would allow him to ascend to power. It was a deranged idea he would later testify to have read, somehow, between the lines of The Beatles’ 1968 White Album, a dark, sparse and – particularly on John Lennon’s more nihilistic songs – acerbic masterpiece of a double album that almost sucked the colour from the psychedelic age single-handed.

On the album’s release, Manson played it over and over again at The Family’s run-down Western film-set headquarters at Spahn Ranch, convinced that The Beatles were sending him coded messages in every song. The avant-garde collage piece “Revolution 9”, he believed, was a reference to Revelations 9, a biblical passage which speaks of a “bottomless pit”; Manson took this as a sign to hide and grow his Family in a cave in Death Valley while the race war waged. “It was the Beatles’ ‘Revolution 9’ that turned me on to it,” he told Rolling Stone. “It predicts the overthrow of the Establishment. The pit will be opened, and that’s when it will all come down. A third of all mankind will die.”

Lennon track “Glass Onion” was read as a prediction of a wall of water that would open for The Family in the desert. “Blackbird” and “Rocky Raccoon” as premonitions of the black American uprising. George Harrison’s anti-elitist ditty “Piggies” inspired The Family to openly discuss killing the wealthy around campfires after Manson’s preaching sessions. And “Helter Skelter”, Paul McCartney’s frenzied rock song that would become one of the bedrocks of heavy metal, was the clearest message of all. “‘Helter Skelter’ is confusion,” Manson said in court, “confusion is coming down fast.”

“It sounded like chaos and destruction,” said ex-Family member Dianne Lake in her book Member of the Family. “From then on, the song title stood as our not-so-secret code name for the race war between the blacks and whites and the coming apocalypse.”

Some argue that it’s an oversimplification to point to the Manson murders as the point at which the Sixties hippie dream died. The decade had long been riven with political assassinations, international war and civil unrest. But these horrific events undoubtedly shifted the tone of a counterculture which otherwise might have remained idealistic and hopeful even through the deaths of The Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, and possibly even the Stones’ notorious 1969 show at Altamont that December.

“It stopped everyone in their tracks,” Ringo Starr said of the Manson murders. “Suddenly all this violence came out in the midst of all this love and peace and psychedelia. Everyone got really insecure. Not just the rockers but everyone in LA felt, ‘Oh God, it can happen to anybody.’” In the wake of the murders, the previously open-door Laurel Canyon scene became more guarded and insular. “Everyone was terrified,” said Michelle Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas. “I carried a gun in my purse. And I never invited anybody over to my house again.”

Ozzy Osbourne, who would record a 1988 song about the Manson murders called “Bloodbath in Paradise”, credited the killings with turning the musical mood towards darker themes as hard rock and heavy metal emerged in the early Seventies. “The Manson murders were all over the telly, so anything with a dark edge was in big demand, he wrote in his autobiography I Am Ozzy. “Before he turned psycho, Manson had been a big part of the LA music scene. If he hadn’t gone to jail, we probably would have ended up hanging out with him.”

That Manson was indeed embedded in the West Coast music and counterculture world was particularly fatal to the “California Dreamin’” fantasy, It exposed the dark alter ego of Sixties LSD idealism and made the murders the most shocking thing ever to happen in or around the hippie scene. Having been taught to play guitar by a gang leader in McNeil Island prison in Washington – his early crimes included armed robbery, car theft, forgery, pimping and rape – Manson built his following as a guru in the hippie enclave of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, using LSD and what his therapist David Smith described as “unconventional sexual practices” to lure followers – often young, insecure, socially outcast women – into his burgeoning cult and “submit totally to his will”.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

And Manson’s musical connections stretched far beyond a warped obsession with The Beatles. His initial clutch of around 20 followers included several musicians. Bobby Beausoleil – who, in the first “Helter Skelter” killing, would murder Family associate Gary Hinman on Manson’s orders shortly before the Tate-LaBianca murders – was a former porn actor who had played in a formative version of Arthur Lee’s Love and went on to record nine albums with his prison band. Beausoleil’s softcore co-star Catherine Share, another Family recruit, had released a folk pop single called “Ain’t It?, Babe” as Charity Shayne in 1965. And of course, despite only being able to knock out a few rough chords, Manson himself was an aspiring singer-songwriter, an ambition fundamentally entwined with the horrors to come.

In April 1968, Family members Ella Jo Bailey and Patricia Krenwinkel were picked up by The Beach Boys’ drummer Dennis Wilson while hitch-hiking in Malibu; Wilson dropped them where they needed to go. A few days later, he saw the girls out on the highway again, and this time took them back to his Sunset Boulevard home. “It was a set-up,” Wilson’s bandmate Al Jardine later said. “Manson would always have the girls out on the highway, hitch-hiking – and Dennis always liked a pretty girl. He picks up the girls, takes them home… and Charlie comes back with a bus, and moves in.”

Manson had been a big part of the LA music scene. If he hadn’t gone to jail, we probably would have ended up hanging out with him

By that evening, much of the Family was occupying Wilson’s house, partying wildly and placing Manson within grasping distance of fame. Wilson was fascinated by Manson – whom he called The Wizard – and his songs, paying for sessions at Gold Star Studios and arranging for Brian and Carl Wilson to produce 10 Manson tracks at Brian’s home studio. One regular visitor to Wilson’s house was Neil Young, who jammed with Manson there.

“We just hung out,” Young said in the biography Shakey. “He played some songs for me, sittin’ in Will Rogers’s old house, on Sunset Boulevard. Dennis had the house there, and I visited Dennis a couple of times … Charlie was always there … He was an angry man. But brilliant. Wrong, but stone-brilliant … Made up songs as he went along, new stuff all the time, no two songs were the same. I remember playin’ a little guitar while he was makin’ up songs.” Young was impressed enough by Manson’s “fascinating” songs to recommend him to a record label friend. “I told Mo Ostin about him, Warner Brothers – ‘This guy is unbelievable’ – he makes up the songs as he goes along, and they’re all good … Never got any further than that. Never got a demo.”

Young gifted Manson a motorcycle and would later write a song called “Revolution Blues”, inspired by him: “I hear that Laurel Canyon is full of famous stars,” Young sang, “but I hate them worse than lepers and I’ll kill them in their cars.” Dennis Wilson, meanwhile, took a Manson number named “Cease to Exist”, rewrote the words and released it as “Never Learn Not to Love” on the B-side of The Beach Boys’ 1968 single “Bluebirds over the Mountain”. The song was credited solely to Wilson since, he explained, Manson had exchanged his publishing rights for “about a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of stuff” (another motorcycle and some cash). Manson was far more aggrieved over Wilson changing the lyrics he’d written specifically about the widening personal fractures within the Beach Boys. According to Van Dyke Parks, Manson responded by leaving a single bullet with Wilson’s housekeeper, to be passed on with a message threatening his children. A reminder, if one were needed, that for all his musical pretensions, Manson was a violent psychopath of unspeakable evil.

By now, Wilson had grown frightened of Manson and his coterie, who had trashed several of his cars and very much outstayed their welcome. Wilson moved out, leaving The Family in the house until The Beach Boys’ manager chased them from the premises to a new base at Spahn Ranch. But not before Wilson had introduced Manson to several music industry insiders, including The Byrds’ producer Terry Melcher. Melcher invited Manson to his home at 10050 Cielo Drive to discuss a possible recording arrangement but, after several aborted attempts to audition him at Spahn, eventually rejected Manson’s music. It was the same address where – looking to strike a blow against the wealthy, powerful and dismissive elites – The Family would later murder Tate, who had leased the house six months earlier with her husband Roman Polanski.

I told Mo Ostin about him, Warner Brothers – ‘This guy is unbelievable’ – he makes up the songs as he goes along, and they’re all good … Never got any further than that

“Terry Melcher, in his house at the top of Cielo Drive, with his power and his money, was the focus for the bitterness and sense of betrayal The Family felt for all the phony Hollywood hippies who kept silencing the truth that Charlie had to share,” Family member and murderer Tex Watson wrote in his 1977 book Will You Die For Me?. “These ‘beautiful people’, Terry and all the others, were really no different from the rich piggies in their white shirts, ties and suits. and just like them, they too deserved a damn good whacking.”

There has been much speculation that Manson’s rejection by the music industry sparked his murderous plans, but he would soon get some sliver of the musical validation he craved. While in custody over the Tate-LaBianca murders, a collection of his Gold Star Studios recordings called Lie: The Love and Terror Cult was released on his old prison friend and Family member Phil Kaufman’s Awareness label in 1970. It featured Manson’s original “Cease to Exist” amongst its grainy lo-fi takes on country folk ballads, off-kilter psychedelia, spoken word drones and cult-like derangement. “Sick city so long, goodbye and die,” he sang on “Sick City”; elsewhere women from The Family babbled and wailed in disturbing, witchy tones. Real seventh circle sounds.

Only 300 of the 2,000 copies were sold but the release has given later acts a means of syphoning off some of Manson’s pure sonic evil. Marilyn Manson has naturally covered and sampled him on an unreleased version of “Sick City” and his own “My Monkey”, earning him a demented, nonsensical personal letter from Manson himself: “Ghost dancers slay together and you’re just in my grave Sunstroker Corona-coronas-coronae,” he wrote. Others to cover or reference Manson in song include Guns N’ Roses, Sonic Youth, the Ramones, shock punk GG Allin, Rob Zombie, The Brian Jonestown Massacre and – rather less fittingly – The Lemonheads and Devendra Banhart.

None took their Manson obsession as far as Trent Reznor, though. The Nine Inch Nails frontman actually rented 10050 Cielo Drive in search of the perfect haunted vibe for his 1994 album The Downward Spiral. He recorded on a studio set-up he built there, nicknamed “Pig”. Such proponents of the darker musical arts might feel they owe some twisted debt to Manson for turning the technicolour decade black, but they miss the point. He’s there, forever, in Beach Boys and Beatles records, corroding the flower power generation from the root up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments