The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

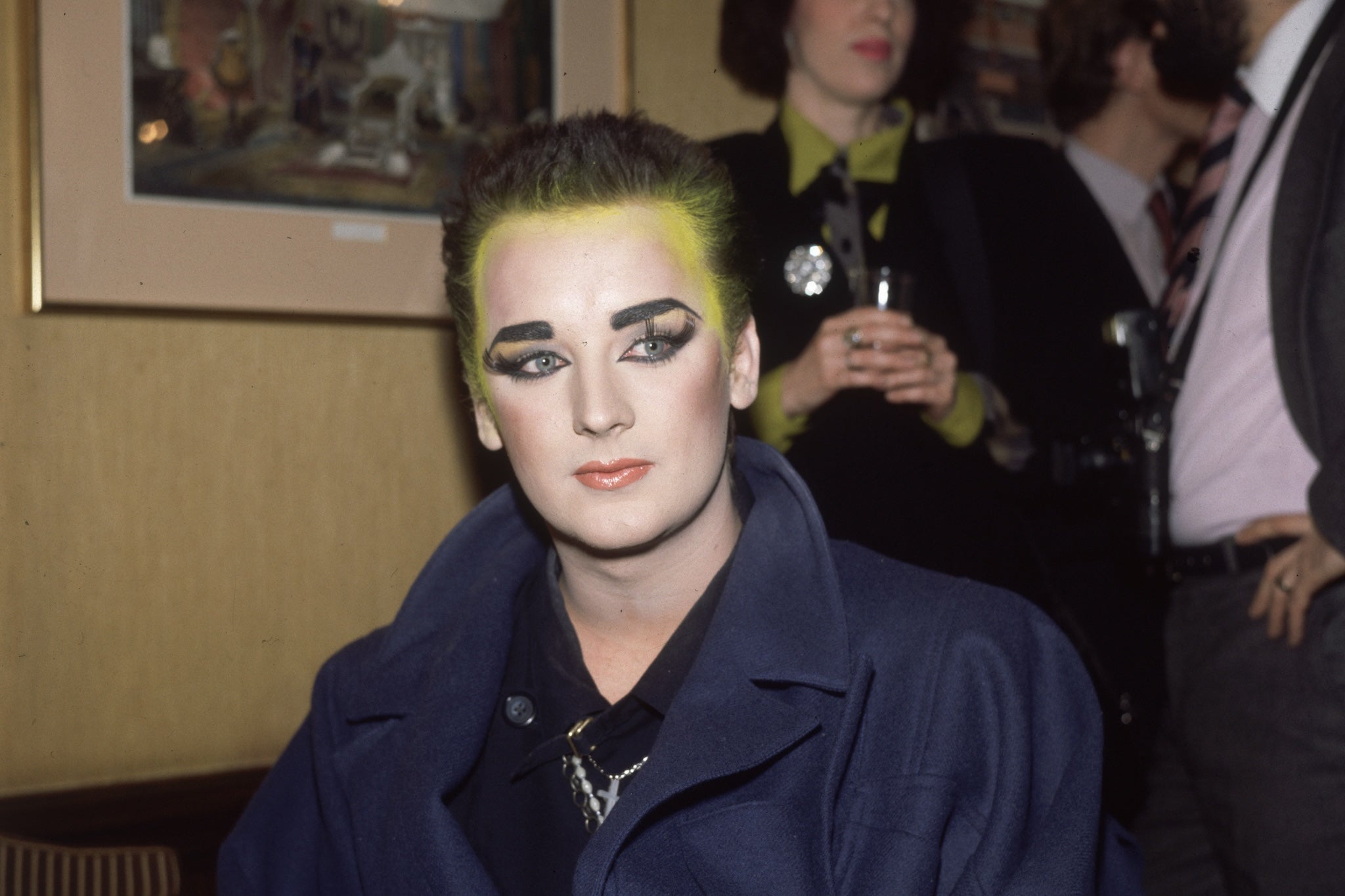

Boy George: ‘When I called someone “a white”, I meant naff’

The Culture Club star talks to Kate Mossman about reviving his most controversial song, finding peace with his violent father, being a b**** to Madonna and what made him paint Margaret Thatcher

Boy George recently broke his finger slipping down the stairs in socks. He is happily back living in Hampstead, having previously been forced to move out of his £20m house there and rent in Hackney Central to cover a colossal lawsuit by his former bandmate Jon Moss. He wears a splint on his finger that functions as a “mini trapeze” – it’s changed his signature somewhat. He has a red bowler hat so high that it could have several other hats under it; if he were to take it off, it would reveal a Star of David he had tattooed on his scalp when drunk.

There are pentangles on his shirt, and a large winter coat draped over him in a way that looks like he is wearing his entire wardrobe at once. He is beautiful. He does not dress like this on the tube – of course he doesn’t. On the tube, he sports a baseball cap, looks “like someone’s dad”, and can go about pretty much unnoticed.

I’ve been told not to ask him about drugs or prison or money – three things that make Boy George one of the most fascinating pop stories of all time. He’s done community service (for falsely reporting a burglary) at the New York City Department of Sanitation, where he had to pick up litter wearing an orange boiler suit. And he’s done time, for the false imprisonment of a Norwegian male model, whom he chained to a radiator. One night in HM Prison Holloway, they screened a documentary about him, which made other inmates disposed to be his friend.

But he’s had a lot of fallings-out in his time. He went to Madonna’s show a few months back and she snubbed him backstage. “I was in this room with all her friends and she didn’t say hello. RuPaul and Madonna are quite similar: if they don’t like you, everyone around them has to hate you too. It’s like being at school with the cool kids.” In the Eighties, Madonna shook his hand and George allegedly said, “Ugh, I don’t know where it’s been.” Now he says: “I have been a total bitch, there’s no denying it. And to her credit, she never responds. Very Leo.” (Madonna’s star sign, not the film star.)

Boy George has always found it hard to resist a pop at other pop stars. He had a spat with Liam Payne on X/Twitter, who he claimed had refused a picture with his niece backstage. “He’s off his nut,” he wrote under a video of Payne taken the day before the former One Direction star died in October after falling from a third-floor balcony in Argentina. Later, on a podcast that was broadcast on the day of Payne’s funeral, he expressed deep regret over his comment: “It wasn’t very nice, but I felt it. I felt like he was out of control.” We meet several weeks later, when he tells me, “It’s very, very sad. I cried when I found out.” Did it surprise him that such a thing could befall a musician in an age so much more sanitised than the one he emerged from? “I have no answers, only questions,” he says.

You get the sense that his relationship with journalists is better than his relationship with other musicians. Boy George was the first pop star to migrate from the gossip pages to the cover stories – before him, they were just entertainment news. He had 20 tabloid covers in the Eighties, which sold so many copies that all the papers started pop columns. But with his £500-a-day heroin habit, he turned himself inside out: his own brother David even went to The Sun for help (“Junkie George has eight weeks to live”). In 1988, the cultural critic Jon Savage said that George, arrested for heroin possession as part of “Operation Culture”, had become an instrument of Margaret Thatcher, and part of the Tory morality narrative.

“Oh really?” he says, nonplussed. “I’d not heard that one before. I was never one of those traumatised homosexuals.” Much more fun to play with the idea that he loved the “Iron Lady”. A few months ago, he sat painting in his studio – not a lot of people know this, but Boy George does striking Pop Art-style paintings – and to his surprise, Maggie herself started to emerge from the canvas. “She just appeared! I was like, ‘Oh God, it’s Thatcher!’” She was bought by a man from Birmingham, who was actually a genuine Thatcher fan “and he was asking me how I felt about her, and I was like, ‘Well, you know, she was iconic, she was legendary, you couldn’t really forget her…’”

George previously had a picture taken with Thatcher at a charity event in the 1990s (“It was like the Eiffel Tower was walking into the room.”) But he’s a socialist really. He recently did a painting of a miserable Meghan at the Queen’s funeral, and another called “47 Reasons to Cry about Trump”. Then he’s suddenly serious: “I hope Trump’s got no time to think about drag queens. And women’s rights aren’t a political issue,” he says – meaning they shouldn’t be decided by Republican men. “I have always thought that since I was a kid; it makes me so angry. Women must decide what they want. This idea that women have abortions because it’s easier. I know loads of women who have never got over it. I have people close to me that still, 30 years later, say, ‘What if?’ So don’t f***ing tell me that it’s done on a whim.”

He tries to rise above politics in general. Boy George in 2024 is a strange mixture of Zen positivity and unstoppable speech. “I’ve done three podcasts in the last three days, I’m like, ‘Sh**, I can’t talk any more!’ But then I realised I can!” He adheres to the “Three Principles”, the idea that our experience of our life is created by our thoughts. And he says he loves the ordinary little things in life: “I bead and I sew, and I concentrate on what I’m doing, to the point where I’m following the needle and the cotton.” He is wedded to the wisdom of star signs too. Does he get on with Virgo journalists? “Jon Moss was a Virgo,” he says. “I love them. Though there is that tendency to die on a cross for what you believe to be right…”

Moss, who was once Boy George’s lover, as well as Culture Club’s drummer, sued for being ejected from the band after a slanging match in 2018; he will not feature as part of their nationwide tour this month. The other main differences in the new show are that Boy George sings lower now, and they’re reprising their 1982 track “White Boy”, a controversial choice for those following debates around cultural appropriation.

“There was a long time we wouldn’t play ‘White Boy’,” he says. “When I called someone a white, I meant naff, you know, because for me, Black people were cool. We were flirting with the whole reggae/Jamaican thing, and my look was a quasi-queer Rastafari. It offended a lot of people at the time!” Some Rastafarians, he explains, “would be like, ‘Righteous!’ [but] there were people who said, ‘Kill him!’”

Though he hasn’t ruled out renting out his house again, he is in a good place financially – he’s just signed a big deal with the entertainment company Live Nation and he did TV show The Voice in Australia. But he wishes people knew more about his songwriting. “I don’t get played on the radio, but I’ve released 54 tracks in the last few months!”

Geldof had started the ball rolling and I remember thinking, ‘Bossy b*******’

He is much more relaxed on stage these days: “I realised, all the crowd want is for you to pull it off. They don’t want you to be faffing! They haven’t come for Boris Johnson.” He leaves his dressing room door open, tries to go with the flow. He encourages this in his team, too.

“Even today, for example, my makeup artist, Christine, we’ve got this big shoot tomorrow for the tour, we’re doing some amazing old looks and we have 10 models. Christine’s like, ‘I’m not doing 10 models.’ I said, ‘Babe, well, then don’t come. I don’t want someone being a grinch, I want joy tomorrow.’ Then I said to the driver, ‘Drop her off at Highgate Cemetery.’ Ha!”

It is 40 years since he took part in Band Aid’s charity number one single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”, of which he was arguably the star turn. The funny thing about recording it was that “everyone was so incredibly well-behaved”: Paul Weller, Bananarama and Marilyn all slipped into school mode. “Geldof had started the ball rolling and I remember thinking, ‘Bossy b*******!’”

He only picked up the call from Geldof because he was Irish, like him. One of six children born to builder Jerry and mother Dinah, George O’Dowd loved the tough girls at school, the ones smoking in the toilets. “I always felt, ‘I’m meant to be gay.’ I never wished I was straight. Kids in the playground would call me a girl and I’d think, ‘What’s wrong with that? Girls are amazing, f*** off.’”

Then there’s that abrupt change of tone again. “My father beat my mother so badly, and these were girls that could stand up for themselves. Any woman that didn’t take s*** was a goddess to me. And whether it was Joan Collins or some woman on TV putting out a cigarette in a plate of prawns, I wanted my mum to be that woman; to say, ‘I’m leaving.’ Of course, there was no escape.”

The sense that his mother was trapped fed into his love of drag.

“She wasn’t allowed to be glamorous, but she was beautiful and stylish and unfortunately, my dad knocked it out of her. When I was a kid, I’d go mental with excitement if my mum was dressed up.” A friend pointed out recently that his mother gave him permission to be himself. “At first, she resisted. Eventually, it just became, ‘Where’s my wastepaper bin? Ah, you’ve turned it into a hat.’”

He is quiet for a moment.

“Obviously, my dad now, I’m totally cool with him, and he wasn’t all bad.” He’s wrapping it up quickly: his father was creative, he says, with beautiful handwriting – hemmed in by the demands of six kids. Yet it’s hard to imagine their relationship mending. When did that happen?

“After he died.”

During the pandemic Boy George did a sound bath, to the tune of singing bowls and gongs. The therapist told him he was likely to have some vivid experiences. (“I rolled my eyes – as if!”) Then, as he drifted off, his father appeared, sat with his back to him, looking out at a sunset. “He had his shirt off. My mother was always tucking his shirt in his trousers. My dad was like, ‘It’s my house, I’ll do what the f*** I want. If I want to fart, I’ll fart.’ So there he was, with his back to me. It was great. It felt like I had nothing to say.”

It was a turning point, and he’s been on a “creative joyride” ever since: writing, composing, sewing and beading: “Sometimes I stay in the studio till it’s dark and laugh at what I’m doing: ‘I’m insane, why am I doing this?’”

His legacy, as far as the rest of us are concerned, might be that Boy George was only ever himself. Every time he hit rock bottom, he re-emerged somehow even more Boy George than before.

“When I was younger, I was running on youthful exuberance, and I’ve gone full circle and become a bit more like I was when I was 14. A little less defensive, a bit more trusting. But I’ve always been driven by the sort of thrill of being in the game, getting my hands dirty. That’s why I never wear nail varnish, because I just can’t keep it on.”

Boy George & Culture Club are on tour in the UK and Ireland from 3 December, concluding at the O2 Arena in London on 15 December; more information and tickets here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments