Bob Dylan interview: 'Passion is a young man's game, older people gotta be wise'

UK exclusive: Folk legend on why he's taking a turn as a crooner for his latest album

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Bob Dylan releases Shadows in the Night, his unique take on some of America's best-loved songs, he talks technique and tradition, giving a rare insight into his own influences and philosophy on life:

Q: After several critically acclaimed records of original songs, why did you make this record now?

A: Now is the right time. I've been thinking about it for a while ever since I heard Willie [Nelson's] Stardust record in the late Seventies. I thought I could do that, too. So I went to see Walter Yetnikoff, the president of Columbia Records. I told him I wanted to make a record of standards, like Willie's. What he said was: "You can go ahead and make that record, but we won't pay for it, and we won't release it. But go ahead and make it if you want to." So I went and made Street Legal instead. In retrospect, Yetnikoff was probably right. It was most likely too soon for me to make a record of standards.

All through the years, I've heard these songs being recorded by other people and I've always wanted to do that. And I wondered if anybody else saw it the way I did. I was looking forward to hearing Rod [Stewart]'s records of standards. I thought if anybody could bring something different to these songs, Rod certainly could. But the records were disappointing. Rod's a great singer, but there's no point putting a 30-piece orchestra behind him. I'm not going to knock anybody's right to make a living, but you can always tell if somebody's heart and soul is into something, and I didn't think Rod was into it in that way. It sounds like so many records where the vocals are overdubbed, and these kind of songs don't come off well if you use modern recording techniques.

To those of us who grew up with these kinds of songs and didn't think much of it, these are the same songs that rock 'n' roll came to destroy - music hall, tangos, pop songs from the Forties, foxtrots, rumbas, Irving Berlin, Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Hammerstein. Composers of great renown. It's hard for modern singers to connect with that kind of music and song.

When we finally went to record, I had about 30 songs, and these 10 fall together to create a certain kind of drama. They all seem connected in one way or another. We were playing a lot of these songs at sound checks on stages around the world without a vocal mic, and you could hear everything pretty well. You usually hear these songs with a full-out orchestra, but I was playing them with a five-piece band and didn't miss the orchestra. Of course, a producer would have come in and said: "Let's put strings here and a horn section there." But I wasn't going to do that. I wasn't even going to use keyboards or a grand piano. The piano covers too much territory and can dominate songs like this in ways you don't want it to.

Q: It's going to be something of a surprise to your traditional fans, don't you think?

A: Well, they shouldn't be surprised. There's a lot of types of songs I've sung over the years, and they definitely have heard me sing standards before.

Glimpses of three paintings in Bob Dylan's Drawn Blank Series collection

Q: Did you know many of these songs from your childhood? Some of them are pretty old.

A: Yeah, I did. I don't usually forget songs if I like them.

Q: What was your process like?

A: Once you think you know the song, then you have to go and see how other people have done it. One version led to another until we were starting to assimilate even Harry James' arrangements. Or even Pérez Prado's. My pedal steel player is a genius at that. He can play anything from hillbilly to bebop. There are only two guitars in there, and one is just playing the pulse. Stand-up bass is playing orchestrated moving lines. It's almost like folk music in a way. I mean, there are no drums in a Bill Monroe band. Hank Williams didn't use them either. Sometimes the beat takes the mystery out of the rhythm. I could only record these songs one way, and that was live on the floor with a very small number of mics. No headphones, no overdubs, no vocal booth, no separate tracking. I know it's old-fashioned, but to me it's the only way that would have worked for songs like this. Vocally, I think I sang about 6in away from the mic. It's a board mix, for the most part, mixed as it was recorded. We played the song a few times for the engineer. He put a few mics around. I told him we would play it as many times as he wanted. That's the way each song was done.

Read more:

Q: It is a very intimate rendering of this material. I assume that's what you wanted.

A: Exactly. We recorded it in the Capitol studios, which is good for a record like this. But we didn't use any of the new equipment. The engineer had his own equipment left over from bygone days, and he brought all that in.

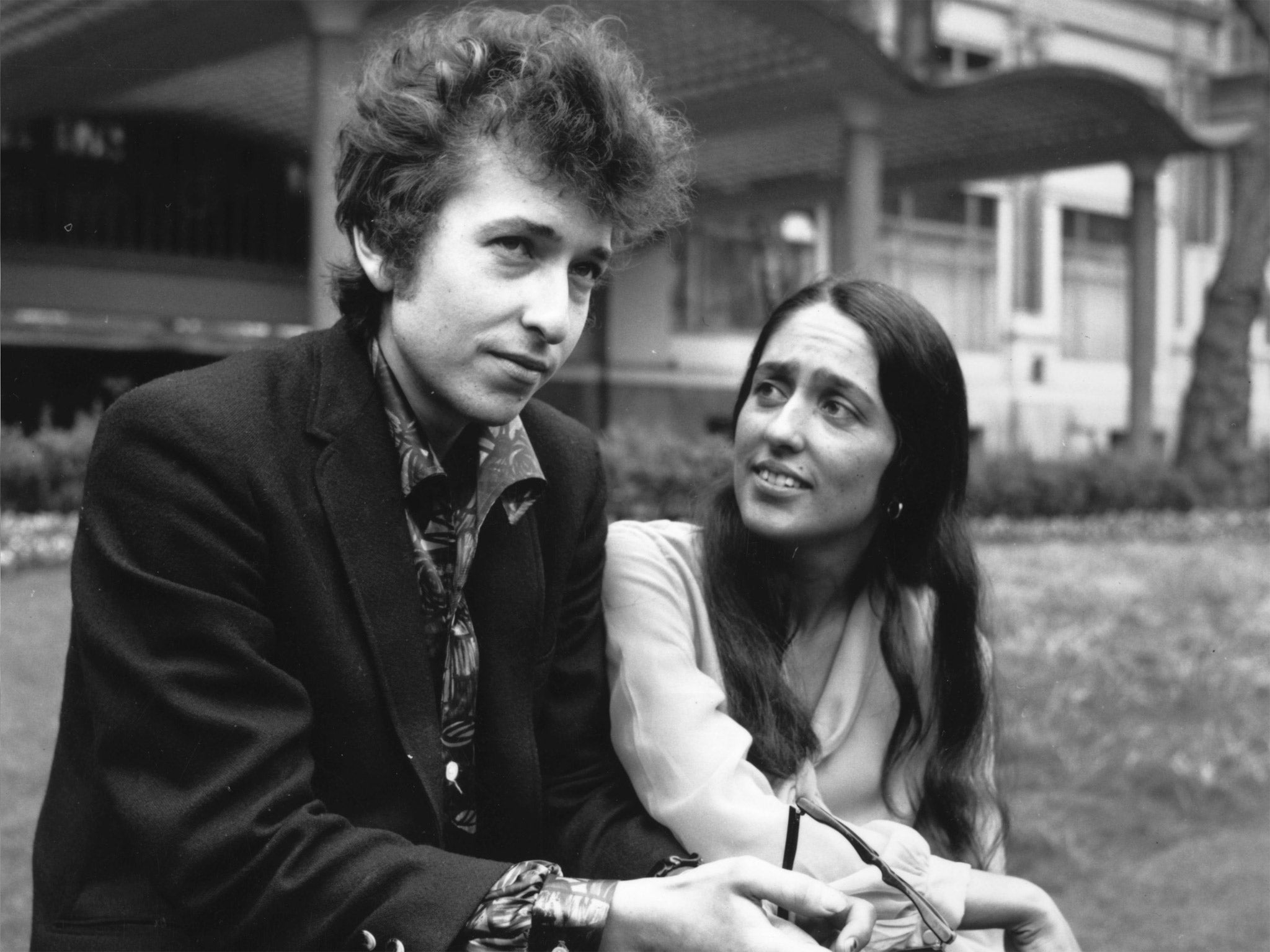

Bob Dylan in 1968

Q: Did you do the arrangements?

A: No. The original arrangements were for up to 30 pieces. We couldn't match that and didn't even try. What we had to do was fundamentally get to the bottom of what makes these songs alive. We took only the necessary parts to make that happen. In a case like this, you have to trust your own instincts.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Q: Did you listen to multiple versions and then throw them away, cleanse your palate and come up with your own version?

A: Well, a lot of these songs, you know, have been pounded into the ground over the years. I wanted to use songs that everybody knows or thinks they know. I wanted to show them a different side of it and open up that world in a more unique way. You have to believe what the words are saying and the words are as important as the melody. Unless you believe the song and have lived it, there's little sense in performing it. "Some Enchanted Evening" - that would be one. Another one would be "Autumn Leaves". You sing that and you have to know something about love and loss and feel it just as much, or there's no point in doing it. It's too deep a song. A schoolboy could never do it convincingly.

People talk about Frank [Sinatra] all the time - and they should talk about Frank - but he had the greatest arrangers. They worked for him in a different kind of way than they worked for other people. They gave him arrangements that are just sublime on every level. And he, of course, could match that because he had this ability to get inside of the song in a sort of a conversational way. Frank sang to you, not at you, like so many pop singers today. Even singers of standards. I never wanted to be a singer that sings at somebody. I've always wanted to sing to somebody. I would have gotten that subliminally from Frank many years ago.

Q: This is a wide-ranging curation of songs from what people call the American Songbook. But I noticed that Frank recorded all 10 of them. Was he on your mind?

A: You know, when you start doing these songs, Frank's got to be on your mind. Because he is the mountain. That's the mountain you have to climb, even if you only get part of the way there. And it's hard to find a song he did not do. He'd be the guy you got to check with.

Q: You've written about how Frank's version of "Ebb Tide" knocked you back on your heels in the Sixties. But you said: "I couldn't listen to the stuff now. It wasn't the right time."

A: Totally... yeah. Really. There are a lot of things like that in my past that I've had to let be and keep moving in my own direction. It would overwhelm me at times, because that's a world that is not your world. "Ebb Tide" was a song that I kind of grew up with. It was a hit song, a pop song. Roy Hamilton did it and he was a fantastic singer, and he did it in a grandiose way. And I thought I knew it. Then I was at somebody's house, and they had one of Frank's records, and "Ebb Tide" was on it. I must have listened to that thing 100 times. I realised then that I didn't know it. I still don't know it to this day. I don't know how he did it. The performance hypnotises you. I never heard anything so supreme - on every single level.

Q: Maybe that music was just too square to admit to liking back then?

A: Square? I don't think anybody would have been bold enough to call Frank Sinatra square. Kerouac listened to him, along with Bird [Charlie Parker] and Dizzy [Gillespie]. But I myself never bought any Frank Sinatra records back then, if that's what you mean. I never listened to Frank as an influence. All I had to go on were records, and they were all over the place, orchestrated in one way or another. Swing music, Count Basie, romantic ballads, jazz bands - it was hard to get a fix on him. But like I say, you'd hear him anyway. You'd hear him in a car or a jukebox. You were conscious of Frank Sinatra, no matter what age you were. Certainly nobody worshipped Frank Sinatra in the Sixties like they did in the Forties. All those other things that we thought were here to stay, they did go away. But he never did.

Q: Do you think of this album as risky? These songs have fans who will say you can't touch Sinatra's version.

A: Risky? Like walking across a field laced with land mines? Or working in a poison gas factory? There's nothing risky about making records. Comparing me with Frank Sinatra? You must be joking. To be mentioned in the same breath as him must be some sort of high compliment. Nobody touches him. Not me or anyone else.

Q: What do you think Frank would make of this album?

A: I think first of all he'd be amazed I did these songs with a five-piece band. I think he'd be proud in a certain way.

On Frank Sinatra, Dylan says: 'To be mentioned in the same breath as him must be some sort of high compliment'

THE HISTORY

Q: What other kinds of music did you listen to growing up?

A: Early on, before rock 'n' roll, I listened to big band music - anything that came over the radio - and music played by bands in hotels that our parents could dance to. We had a big radio that looked like a jukebox, with a record player on the top. All the furniture had been left in the house by the previous owners, including a piano. The radio/record player played 78rpm records. And when we moved to that house, there was a record on there, with a red label, and I think it was a Columbia record. It was Bill Monroe, or maybe it was the Stanley Brothers, and they were singing "Drifting Too Far From Shore". I'd never heard anything like that before. Ever. And it moved me away from all the conventional music that I was hearing.

To understand that, you'd have to understand where I came from. I come from way north. We'd listen to radio shows all the time. I think I was the last generation, or pretty close to the last one, that grew up without TV. So we listened to the radio a lot. Most of these shows were dramas. For us, this was like our TV. Everything you heard, you could imagine what it looked like. Even singers that I would hear on the radio, I couldn't see what they looked like, so I imagined what they looked like. What they were wearing. What their movements were. Gene Vincent? When I first pictured him, he was a tall, lanky blond-haired guy.

A: Up north, you could find these radio stations with no name on the dials that played pre-rock 'n' roll things - country blues. We would hear Slim Harpo or Lightnin' Slim and gospel groups, the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Five Blind Boys of Alabama. I was so far north, I didn't even know where Alabama was. And then there'd be, at a different hours, the blues - you could hear Jimmy Reed, Wynonie Harris and Little Walter. Then there was a station out of Chicago. Played all hillbilly stuff. Riley Puckett, Uncle Dave Macon, the Delmore Brothers. We also heard the Grand Ole Opry from Nashville every Saturday night. I heard Hank Williams way early, when he was still alive. A lot of those Opry stars, except for Hank, of course, came through the town I lived in and played at the armory building. Webb Pierce, Hank Snow, Carl Smith, Porter Wagoner. I saw all those country stars, growing up.

One night I was lying in bed and listening to the radio. I think it was a station out of Shreveport, Louisiana. I wasn't sure where Louisiana was either. I remember listening to The Staple Singers' "Uncloudy Day". And it was the most mysterious thing I'd ever heard. It was like the fog rolling in. I heard it again, maybe the next night, and its mystery had even deepened. What was that? How do you make that? It just went through me like my body was invisible. What is that? A tremolo guitar? What's a tremolo guitar? I had no idea, I'd never seen one. And what kind of clapping is that? And that singer is pulling things out of my soul that I never knew were there. After hearing it for the second time, I don't think I could even sleep that night. I knew these Staple Singers were different than any other gospel group. But who were they anyway?

I'd think about them even at my school desk. I managed to get down to the Twin Cities and get my hands on an LP of The Staple Singers, and one of the songs on it was "Uncloudy Day". And I'm like, "Man!" I looked at the cover and studied it, like people used to do with covers of records. I knew who Mavis was without having to be told. I knew it was she who was singing the lead part. I knew who Pops was. All the information was on the back of the record. Not much, but enough to let me in just a little ways. Mavis looked to be about the same age as me in her picture. Her singing just knocked me out. I listened to the Staple Singers a lot. Certainly more than any other gospel group. I like spiritual songs. They struck me as truthful and serious. They brought me down to earth and they lifted me up all in the same moment. And Mavis was a great singer - deep and mysterious. And even at the young age, I felt that life itself was a mystery.

This was before folk music had ever entered my life. I was still an aspiring rock 'n' roller, the descendant, if you will, of the first generation of guys who played rock 'n' roll - who were thrown down. Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis. They played this type of music that was black and white. Extremely incendiary. Your clothes could catch fire. It was a mixture of black culture and hillbilly culture. When I first heard Chuck Berry, I didn't consider that he was black. I thought he was a white hillbilly. Little did I know, he was a great poet, too. "Flying across the desert in a TWA, I saw a woman walking 'cross the sand. She been walking 30 miles en route to Bombay to meet a brown-eyed handsome man." Only later did I realise how hard it is to write those kind of lyrics.

Chuck Berry could have been anything in the music business. He stopped where he was, but he could have been a jazz singer, a ballad singer, a guitar virtuoso. But there's a spiritual aspect to him, too. In 50 or 100 years he might even be thought of as a religious icon. There's only one him, and what he does physically is even harder to do. If you see him in person, you know he goes out of tune a lot. But who wouldn't? He has to constantly be playing eighth notes on his guitar and sing at the same time, plus play fills and sing. People think that singing and playing is easy. It's not. It's easy to strum along, but if you actually want to really play, where it's important, that's a hard thing and not too many people are good at it.

Q: And he was always the main guitar player in his band.

A: He was the only guitar player. Yeah. And there was Jerry Lee [Lewis], his counterpart, and people like that. There must have been some elitist power that had to get rid of all these guys, to strike down rock 'n' roll for what it was and what it represented - not least of all it being a black-and-white thing. Tied together and welded shut. If you separate the pieces, you're killing it.

Dylan at a Civil Rights protest in the 1960s

Q: Do you mean it's musical race-mixing, and that's what made it dangerous?

A: Well, racial prejudice has been around a while, so yeah. And that was extremely threatening for the city fathers, I would think. When they finally recognised what it was, they had to dismantle it, which they did, starting with payola scandals and things like that. The black element was turned into soul music and the white element was turned into English pop. They separated it. I think of rock 'n' roll as a combination of country blues and swing band music, not Chicago blues and modern pop. Real rock 'n' roll hasn't existed since when? 1961, 1962? Well, it was a part of my DNA, so it never disappeared from me. [Laughs.] I can't remember what the question was.

Q: We were talking about your influences and your crush on Mavis Staples.

A: Oh, Mavis! So I had seen this picture of The Staple Singers. And I said to myself: "You know, one day you'll be standing there with your arm around that girl." Ten years later, there I was. But it felt so natural. Felt like I'd been there before, many times. Well I was, in my mind.

Q: I was thinking how important it was to you when you were young to chase down those Woody Guthrie records. And about how Mick [Jagger] and Keith [Richards] ran all over London to get blues records. And now the internet has all of it - you can just touch a button and hear almost anything in the history of recorded music. Has it made music better? Or worse? More or less valued?

A: Well, if you're just a member of the general public, and you have all this music available to you, what do you listen to? How many of these things are you going to listen to at the same time? Your head is just going to get jammed - it's all going to become a blur, I would think. Back in the day, if you wanted to hear Memphis Minnie, you had to seek a compilation record, which would have a Memphis Minnie song on it. And if you heard Memphis Minnie back then, you would just accidentally discover her on a record that also had Son House and Skip James and the Memphis Jug Band. And then maybe you'd seek Memphis Minnie in some other places - a song here, a song there. You'd try to find out who she was. Is she still alive? Does she play? Can she teach me anything? Can I hang out with her? Can I do anything for her? Does she need anything? But now, if you want to hear Memphis Minnie, you can go hear a thousand songs. Then it's like, "Oh man! This is overkill!" It's so easy you might appreciate it a lot less.

THE MUSIC

Q: Are the songs on this album laid down in the order you would like people to listen to them? Or do you care whether Apple sells them one by one?

A: The business end of the record is none of my business. But the way people listen to music has changed, and I hope they get a chance to hear all the songs in one way or another. But! I did record those songs, believe it or not, in that same order that you hear them. Not that it matters, really. We would usually get one song done in three hours. There's no mixing. That's just the way it sounded. Capitol's got those big echo chambers, so some of that was probably used, but we used as little technology as possible. It's been done wrong too many other times.

Bob Dylan performs on-stage in June 2009 in California

Q: Was this recording an experiment?

A: It was more than an experiment. It's just a question of could it be recorded right. We did it the old-fashioned way, I guess you would say. That's the way I used to make records anyway. I never did use earphones until into the Eighties or Nineties. I don't like to use earphones.

Q: You feel that's a distancing thing?

A: Yeah. You can overwhelm yourself in your own head. I've never heard anybody sing with those things in their ears effectively. They just give you a false sense of security. A lot of us don't need earphones. I don't think Springsteen or Mick do. But other people more or less have given in. But they ought not to. They don't need to. Especially if they have a good band.

Recording studios are filled with technology. They are set in their ways. And to update them means you'd have to change them back. That would be my idea of upgrading. And this will never happen. As far as I know, recording studios are booked all the time. So obviously people like all the improvements. The more technically advanced they are, the more in demand they become. The corporations have taken over. Even in the recording studio. Actually, the corporate companies have taken over American life most everywhere. Go coast to coast and you will see people wearing the same clothes, thinking the same thoughts, eating the same food. Everything is processed.

Q: Let's talk about the first song on the album, "I'm a Fool To Want You". I'm interested in how you put across the heartbreak on this record. It's believed that Frank Sinatra wrote it for Ava Gardner, his great love. You wrote once that the performer, the artist transmits emotion via alchemy. "I'm not feeling this," you're saying. "What I'm doing is I'm putting it across." Is that right?

A: You're right, but you don't want to overstate that. Look, it all has to do with technique. Every singer has three or four or five techniques, and you can force them together in different combinations. Some of the techniques you discard along the way, and pick up others. But you do need them. It's just like anything. You have to know certain things about what you're doing that other people don't know. Singing has to do with techniques and how many you use at the same time. One alone doesn't work. There's no point to going over three. But you might interchange them whenever you feel like it .So yes, it's a bit like alchemy.

It's different than being an actor, where you call up sources from your own experience that you can apply to whatever Shakespeare drama you're in. But an actor is pretending to be somebody, a singer isn't. And that's the difference. Singers today have to sing songs where there's very little emotion involved. That and the fact that they have to sing hit records from years gone by doesn't leave a lot of room for any kind of intelligent creativity.

In a way, having hits buries a singer in the past. A lot of singers hide in the past because it's safer back there. If you've ever heard today's country music, you'll know what I'm talking about. Why do all these songs fall flat? I think technology has a lot to do with it. Technology is mechanical and contrary to the emotions that inform a person's life. The country music field has especially been hit hard by this. These songs [on my album] have been written by people who went out of fashion years ago. I'm probably someone who helped put them out of fashion. But what they did is a lost art form. Just like da Vinci and Renoir and van Gogh. Nobody paints like that any more either. But it can't be wrong to try.

So a song like "I'm a Fool to Want You": I know that song. I can sing that song. I've felt every word in that song. I mean, I know that song. It's like I wrote it. It's easier for me to sing that song than to sing, "Won't you come see me, Queen Jane". At one time that wouldn't have been so. But now it is. Because "Queen Jane" might be a little bit outdated. It can't be outrun. But this song is not outdated. It has to do with human emotion, which is a constant thing. There's nothing contrived in these songs. There's not one false word in any of them. They're eternal, lyrically and musically.

Q: Do you wish you wrote them?

A: In a way I'm glad I didn't write any of them. I'm good with songs I haven't written, if I like them. I already know how they go, so I have more freedom with them. I understand these songs. I've known them for 40 years, 50 years, maybe longer, and they make a lot of sense. So I'm not coming to them like a stranger. I've written all the songs that I feel are... I don't know how to put this ... You travel the world, you go see different things. I like to see Shakespeare plays, so I'll go - I mean, even if it's in a different language. I don't care, I just like Shakespeare, you know. I've seen Othello and Hamlet and Merchant of Venice over the years, and some versions are better than others. Way better. It's like hearing a bad version of a song. But then somewhere else, somebody has a great version.

Q: I like your version of "Lucky Old Sun". Can you talk about what drew you to this one in particular? Did you have a memory of it?

A: Oh, I've never not known that song. I don't think anybody my age can tell you that they ever remember not knowing that song. I mean, it's been recorded hundreds of times. I've sung it in concert, but I never really got to the heart of the song until recently.

Q: So how do you do that?

A: Well, you cut the song down to the bone and see if it's really there for you to do. Most songs have bridges in them, to distract listeners from the main verses of a song so they don't get bored. My songs don't have a lot of bridges because lyric poetry never had them. But when a song like "Autumn Leaves" presents itself, you have to decide what's real about it and what's not. Listen to how Eric Clapton does it. He sings the song, and then he plays the guitar for 10 minutes and then he sings the song again. He might even play the guitar again, I can't remember. But when you listen to his version, where do you think the importance is? Well obviously, it's in the guitar playing. Now, it's OK for Eric because he's a master guitar player and, of course, that's what he wants to feature on any song he records. But other people couldn't do it and get away with it. It's not exactly getting to the heart of what "Autumn Leaves" is about. And as a performer, you don't get many chances to do that. And when you get the opportunity, you don't want to blow it. With all these songs you have to study the lyrics. You have to look at every one of these songs and be able to identify with them in a meaningful way. You can hardly sing these songs unless you're in them. If you want to fake it, go ahead. Fake it if you want. But I'm not that kind of singer.

Q: Can we talk about some of the melodies?

A: Yeah, they're incredible, aren't they? All these songs have classical music under-themes. Why? Because all these composers learned from classical music. They understood music theory, and they went to music academies. It could be a little piece of Mozart, Bach - Paul Simon did an entire song using a Bach melody - or it could be a piece of Beethoven or Liszt, or Tchaikovsky. You can get a lot of great melodies listening to Tchaikovsky if you're a commercial songwriter.

Most of these songs are written by two people, one for the music and one for the words.There's only one guy that I know of who did it all, and that was Irving Berlin. He wrote the melody and the lyrics. This guy was a flat-out genius. I mean, he had a gift, like, it just wouldn't stop giving, classical themes not withstanding, because I don't think he used any. But everyone else who wrote lyrics had to depend on a piece of music.

THE AUDIENCE

Q: These songs will have a different audience than they originally had. Do you feel like a musical archaeologist?

A: No. I just like these songs and feel I can connect with them. I would hope people will connect with them the same way that I do. It would be presumptuous to think these songs are going to find some new audience, as if they're going to appear out of nowhere. Besides, when I look out from the stage, I see something different than maybe other performers do.

Q: What are you seeing from the stage?

A: Definitely not a sea of conformity. People I cannot categorise easily. I wouldn't say there is one type of fan. I see a guy dressed up in a suit and tie next to a guy in blue jeans. I see another guy in a sport coat next to another guy wearing a T-shirt and cowboy boots. I see women sometimes in evening gowns and I see punky-looking girls. Just all kinds of people. I can see that there's a difference in character, and it has nothing to do with age. I went to an Elton John show, and it was interesting. There must have been at least three generations of people there. But they were all the same. Even the little kids. People make a fuss about how many generations follow a certain type of performer. But what does it matter if all the generations are the same? I'm content to not see a certain type of person that could be easily tracked. I don't care about age, but the adolescent youth market, I think it goes without saying, might not have the experience it takes to understand these songs and appreciate them.

Q: The songs on this album conjure a kind of romantic love that is nearly antique, because there's no longer much resistance in romance. People date and they climb into bed. That old sweet, painful pining doesn't exist any more. Do you think these songs will fall on younger ears as corny?

A: You tell me. I mean, I don't know why they would, but what's the word "corny" mean exactly? It's like "tacky". I don't say that word either. There's just no power in those words. These songs, take 'em or leave 'em, if nothing else, are songs of great virtue. That's what they are. If they sound trite and corny to somebody, well so much for that. But people's lives today are filled on so many levels with vice and the trappings of it. Sooner or later, you have to see through it or you don't survive. We don't see the people that vice destroys. We just see the glamour of it on a daily basis - everywhere we look, from billboard signs to movies, to newspapers, to magazines. We see the destruction of human life and the mockery of it, everywhere we look. These songs are anything but that. Romance never does go out of fashion. It's radical. Maybe it's out of step with the current media culture. If it is, it is.

Q: You once said that you came into the music business through the side door, because nobody thought folk music was going to amount to anything in the music business at the time. Now, here you are with this grand parade of iconic American songs. Are you finally coming in through the front door?

A: I would say that's pretty right on. You just have to keep going to find that thing that lets you in the door. Sometimes in life when that day comes and you're given the key, you throw it away. But folk music came at exactly the right time in my life. It wouldn't have happened 10 years later, and 10 years earlier I wouldn't have known what kind of songs those were. They were just so different than popular music. Then folk music became relegated to the sidelines. It either became commercial or the Beatles killed it. Maybe it couldn't have gone on anyway. But actually, in this day and age, it still is a vibrant form of music, and many people sing and play it much better than we ever did. It's just not what you would call part of the pop realm. I had gotten in there at a time when nobody else was there or knew it even existed, so I had the whole landscape to myself. I went into songwriting. I figured I had to - I couldn't be a hellfire rock 'n' roller. But I could write hellfire lyrics.

Q: A lot of your newer songs deal with ageing. You once said that people don't retire, they fade away, they run out of steam. And now you're 73, you're a great-grandfather.

A: Look, you get older. Passion is a young man's game, OK? Young people can be passionate. Older people gotta be more wise. I mean, you're around awhile, you leave certain things to the young and you don't try to act like you're young. You could really hurt yourself.

THE JOY

Q: You obviously get great joy and connection from the people who come to see you.

A: It's not unlike a sportsman who's on the road a lot. Roger Federer, the tennis player, I mean, you know, he's working most of the year. Like maybe 250 days a year, every year, year in and year out. So it's relative. I mean, yeah, you must go where the people are. You can't bring them to where you are unless you have a contract to play in Vegas. But happiness - a lot of people say there is no happiness in this life, and certainly there's no permanent happiness. But self-sufficiency creates happiness. Happiness is a state of bliss. Actually, it never crosses my mind. Just because you're satisfied one moment - saying yes, it's a good meal, makes me happy - well, that's not going to necessarily be true the next hour. Life has its ups and downs, and time has to be your partner, you know? Really, time is your soul mate. Children are happy. But they haven't really experienced ups and downs yet. I'm not exactly sure what happiness even means. I don't know if I personally could define it.

Q: Have you ever held it?

A: We all do at certain points, but it's like water - it slips through your hands. As long as there's suffering, you can only be so happy. How can a person be happy if he has misfortune? Does money make a person happy? Some wealthy billionaire who can buy 30 cars and maybe buy a sports team, is that guy happy? What then would make him happier? Does it make him happy giving his money away to foreign countries? Is there more contentment in that than giving it here to the inner cities and creating jobs? Now, I'm not saying they have to - I'm not talking about communism - but what do they do with their money? Do they use it in virtuous ways? If you have no idea what virtue is all about, look it up in a Greek dictionary. There's nothing namby-pamby about it.

Q: So they should be moving their focus?

A: Well, I think they should, yeah, because there are a lot of things that are wrong in America and especially in the inner cities that they could solve. There are good people there, who can all be working at something. These multibillionaires can create industries right here in the inner cities of America. But no one can tell them what to do. God's got to lead them.

Q: Let me talk to you for a minute about your gift. There are artists like George Balanchine, the choreographer, who felt that he was a servant to his muse. Somebody else like Picasso felt that he was the boss in the creative process. How have you dealt with your own gift over the years?

A: [Laughter] Well, I might trade places with Picasso if I could, creatively speaking. I'd like to think I was the boss of my creative process too. But of course, that's not true. Like Sinatra, there was only one Picasso. As far as George the choreographer, I'm more inclined to feel the same way that he does about what I do. It's not easy to pin down the creative process.

Q: Is it elusive?

A: It totally is. It totally is. It's uncontrollable. It makes no sense in literal terms. But it starts like this. What kind of song do I need to play in my show? What don't I have? It always starts with what I don't have. I need all kinds of songs - fast ones, slow ones, minor key, ballads, rumbas - and they all get juggled around during a live show. I've been trying for years to come up with songs that have the feeling of a Shakespearean drama, so I'm always starting with that. Once I can focus in on something, I just play it in my mind until an idea comes from out of nowhere, and it's usually the key to the whole song. It's the idea that matters. It's like electricity was around long before Edison harnessed it. Communism was around before Lenin took over. So creativity has a lot to do with the main idea. Inspiration is what comes when you are dealing with the idea. But inspiration won't invite what's not there to begin with.

Q: You've been generous to take up all of these questions.

A: I found them really interesting. The last time I did an interview, the guy wanted to know about everything except the music. Man, I'm just a musician, you know? People have been doing that to me since the Sixties - they ask questions like they would ask a medical doctor or a psychiatrist or a professor or a politician. Why? Why are you asking me these things?

Q: What do you ask a musician about?

A: Music! Exactly.

The original interview appeared in 'AARP' magazine. 'Shadows In The Night' is out now on Columbia Records

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments