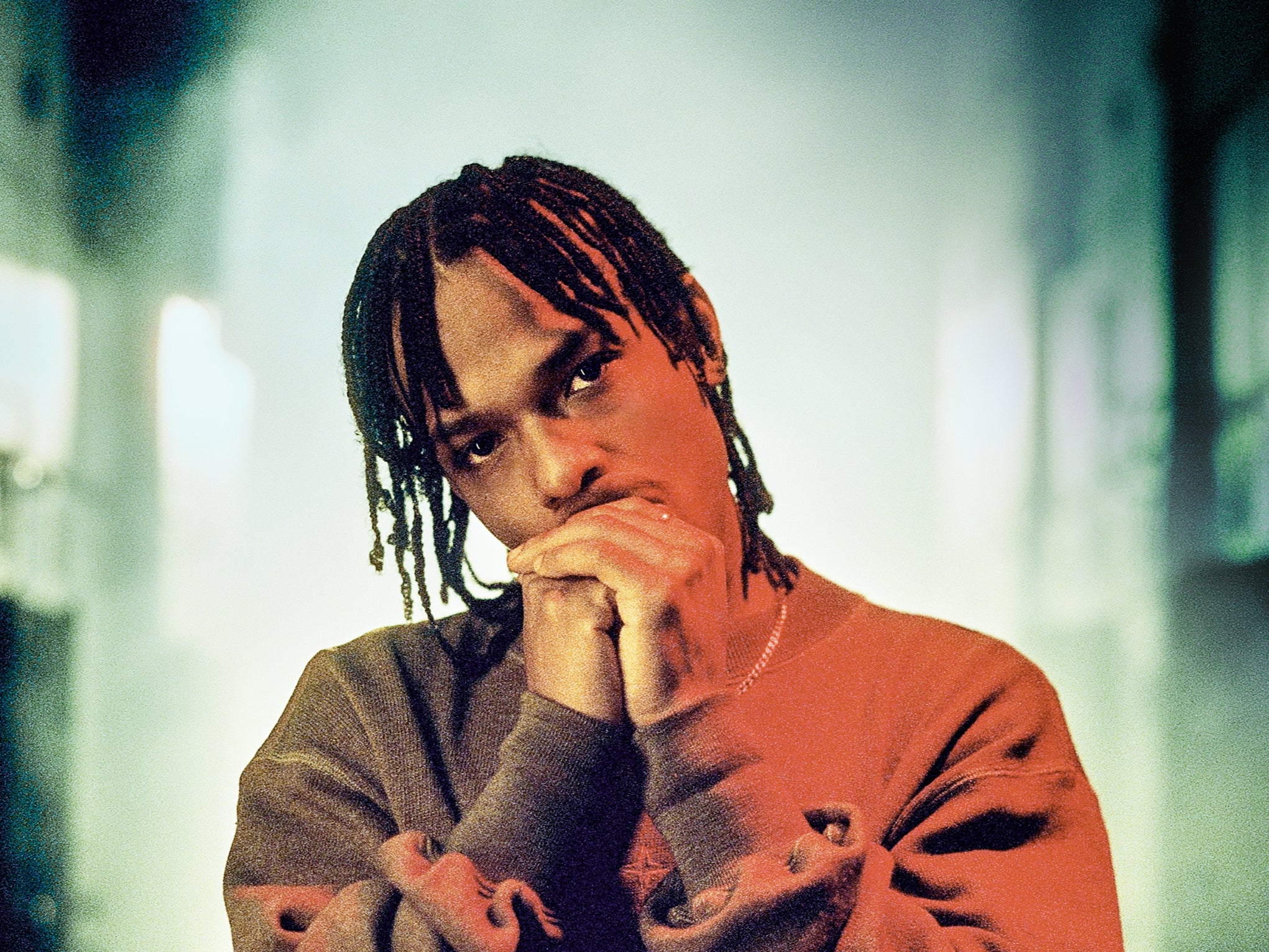

Berwyn: ‘Racism has affected me ever since I came to the UK’

On the eve of the Mercury Prize, the shortlisted rap/R&B artist talks to Sam Moore about his tumultuous upbringing, racism, poverty, and why he’s determined to prove himself against the odds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just over a week before the Mercury Prize is due to take place and Berwyn, whose debut Demotape/Vega is among this year’s shortlisted projects, is sitting at home, nursing a bowl of chicken soup. “I’ve had a crazy, sad life,” the 25-year-old says, sounding hoarse after performances at Reading and Leeds festivals. Even without the sore throat, though, the artist born Berwyn Du Bois borders on reticent. He speaks calmly, slowly; answers amble.

A little over a year ago, few people knew who Berwyn was. Yet two mixtapes, a Drake co-sign and one breathtaking Jools Holland performance later, he looks a lot like the future of British music. His sound melds minimalist, piano-driven R&B with avant-garde raps that barely rise above a mumble; his singing style recalls James Blake and Frank Ocean. Like his fellow crooners, Berwyn demonstrates little to no interest in a life of pop stardom, but he does harbour some lofty ambitions. “My ultimate goal is to be the greatest of my generation,” he announces, managing to come across both sincere and self-deprecating.

His mention of a “s****y life” is about as deep as he’s willing to dive when it comes to his past, at least during this interview. Speaking over Zoom, he reflects on his journey from Trinidad to Romford, aged nine; on a childhood spent watching his mother go in and out of prison. His uncertain immigration status was only just resolved, and there were times when he was forced to sleep in his car. If not for a recent Mercury Prize rule change, allowing non-British passport holders who have been resident in the UK or Ireland for more than five years to submit their work, he wouldn’t be on this year’s shortlist. “It’s been a real s****y life but it’s not finished,” he says. “And it’s OK now. It’s a happy one.”

He’d rather fans listen to the music to hear his stories about seeing first-hand the effects of Britain’s brutalising immigration system, on which he blames for preventing him going to university. Debut single “Glory” is candid and confessional, offering an uncomfortable glimpse into a painful life. Berwyn’s voice cracks authentically as he relives the terror of receiving letters from immigration officials, later growing in defiance as he dreams of purchasing a country estate for his family.

“Glory” also happens to be the song that changed his life. Last June, he was revealed to the world through a segment on Later… with Jools Holland from the intimate settings of his mum’s kitchen (this at a time when full lockdown measures were in place). Wearing a customised black Adidas jacket with BLM printed on the heart, Berwyn fell delicately into the opening bars. He’d written an extra verse the night before, in which he addressed racism and the Black Lives Matter protests that were sweeping the UK and the US at the time. It was profoundly moving.

“Racism has affected me consistently and negatively ever since I came to the UK,” Berwyn says. “Black people are told spooky, scary campfire stories that get stuck [in your head]. It will always have a negative impact on Black men’s mental health.” He’s less concerned with dwelling on history, it seems, and more about celebrating his musical heritage: “Trinidadian music, calypso, [tend to merge] political topics with melody and song.” Berwyn’s father was a DJ and was the one who introduced him to the steelpan. He also takes influence from soca – a genre developed by Ras Shorty I, also known as Lord Shorty, in Trinidad during the Seventies – which is something of a hybrid between calypso and East Indian rhythms). “Growing up, that would have been the earliest form of music I listened to,” Berwyn says. It was when he moved to Romford that he discovered the soul-searching sounds of fellow wordsmiths Kano and Wretch 32.

At school, he discovered a natural talent for the guitar, nurtured by a music teacher who encouraged him to pursue it through his GCSE years. He fears for future artists amid the ongoing cuts faced by arts subjects at schools in the UK. “There was one computer for our entire GCSE class, that’s one computer for an entire group of kids,” he recalls. “It blows my mind. There could have been four other Berwyn’s in that class [if there were more resources].” He hints at an awareness of the UK’s penchant for “poverty porn” in pop culture: “All people want is the pain of the working class, but they don’t want to pay for it.”

Sorrow and suffering do, it seems, transpire naturally in Berwyn’s music. But don’t mistake his explorations of heartbreak and strife – delivered with an unguarded vulnerability – as his own personal therapy. “I find writing songs sacrificial,” he says. “I’m sacrificing my emotions to make money.” When you sit in a dark room going over the “same s***” again and again, he points out, “things can get weird”. During moments of inspiration, he feels compelled to open his “Pandora’s Box” and “hurt myself for a minute and see all the things that make me cry”. He’s acutely aware that this may not be the healthiest way to create art. “You know, it’s kind of f****,” he observes wryly. “I have to cry 100 times so you can cry once.”

I find writing songs sacrificial... I’m sacrificing my emotions to make money

At least he can say with confidence that the looming threat of homelessness is now a thing of the past. Berwyn’s second mixtape, Tape 2/Fomalhaut, was released in June to critical acclaim. It’s a more cohesive expansion on Vega; Berwyn combines muted piano rhythms with harsher trap drums that offer a sinister edge, against which he sharpens his biting political observations. On “I’d Rather Die Than Be Deported”, he raps: “I used to sleep in a foreign/ Wouldn’t really call it a foreign/ Legally I was a no-one/ To everyone I was just foreign.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 4 month free trial (3 months for non-Prime members)

It got people’s attention, and Berwyn now finds himself on the cusp of his biggest career moment to date. Many artists have balked at the pressures a Mercury Prize can bring for a debut artist: Gorillaz famously withdrew their nomination in 2001, saying it would be like “carrying a dead albatross around your neck for eternity“, while critics wondered if Speech Debelle’s 2009 win caused her career to stutter. Yet Berwyn is “over the moon” with the nomination. Quite rightly. Without the privileges of Brit School training or the major label funding enjoyed by so many of his peers, he’s made it here by carving out his own path. The greatest of his generation? He could be.

The Mercury Prize takes place tonight (9 September) at 8pm – fans can watch on BBC iPlayer and BBC Four

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments